MUSK’S PAY DEAL

Who – or what – could follow Elon at Tesla?

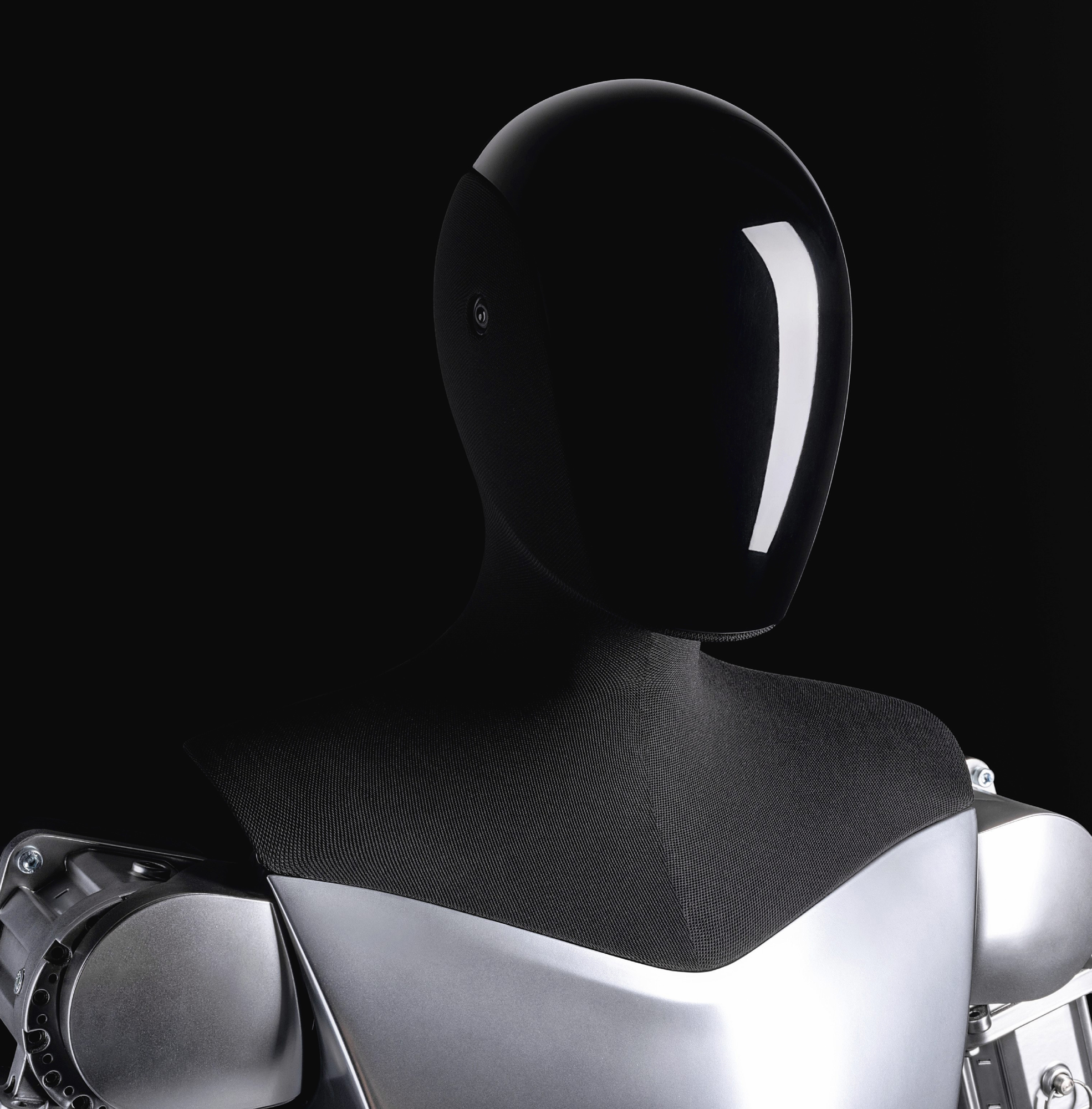

Robots and other non-automotive projects give Musk his huge value

Is Elon Musk really worth a trillion-dollar pay deal? And what would Tesla look like without him? He’s been threatening to reduce his stake or even quit altogether unless he can increase his shareholding to at least a quarter, the level at which he believes he can fend off a takeover bid, or activist investors who might divert or dilute his dictatorial vision for the company.

In response, Tesla chair Robyn Denholm has proposed a trillion-dollar pay package. ‘Retaining and incentivising Elon is fundamental to Tesla becoming the most valuable company in history,’ she wrote to investors.

She’s not wrong. Tesla’s forward price-earnings ratio is a good indicator of the Elon effect. For comparison, GM’s market value is around six times its expected earnings for next year. Tech firms that are expected to do exciting things have higher price-earnings ratios: chip maker Nvidia, which powers the AI revolution and was briefly the world’s most valuable company, trades at around 30 times its earnings.

He might get a lost less than a trillion, but the deal should give Elon what he really wants: control

Tesla, however, currently trades at a frankly ludicrous 170 times its earnings. Its car sales provide all of those earnings but are only a small part of that future value calculation. The fact that sales and profits have dropped just doesn’t figure. Nor does the fact Elon’s politics are alienating significant numbers of buyers.

Instead, that wild price/earnings ratio is based on Tesla’s future robots, robotaxis and AI: what Elon will do next, rather than what he already did. Tesla pays well and has good people, but if the main man goes, the bubble bursts and the share price crashes. His presence and confidence remain everything. Tesla’s value leapt 3.5 per cent when he bought a billion dollars’ worth of shares recently – just a thousandth of its value. If he dumped his shares, the stock would tank utterly.

The public optics of a potential trillion-dollar pay deal aren’t great, but it makes more sense when you get into the details and understand the motivations. The full trillion is only triggered if Musk hits a series of insane-sounding targets: chiefly increasing Tesla’s market capitalisation eight-fold to $8.5tn and increasing its adjusted earnings 24-fold to $400bn, but also a bunch of other, equally punchy ambitions on car and robot sales, autonomous driving subscriptions and vehicles operating on the Robotaxi network.

None of that headline sum is paid in cash: Elon will take no salary or bonus. He will be paid purely in equity, the trillion dollars being the value of the additional 12 per cent of Tesla he will receive if the company is actually worth that $8.5bn in 10 years. The shares will be released in 12 stages, so he doesn’t have to wait 10 years and risk falling short of the ultimate target, but the first stage isn’t activated until he has doubled Tesla’s value to $2tn.

The faithful still treat Musk as rock star and saviour

He might get a lot less than a trillion, and he might get nothing at all, but the deal should give Elon what he really wants: not cash, but control. He could end up with between 25 and 32 per cent of Tesla, depending on tax and dilution. And the majority of shareholders will want this deal too. Their options are either to lock in the man who has made them so much money already, or risk losing him and seeing the value of their shares plummet.

Denholm’s pay deal for Musk also cleverly supports that share price by showing how Tesla plans to get to the crazy future valuation that investors assign it. Elon’s last deal was also thought to be impossible, requiring him to increase Tesla’s value from $59bn to over $600bn. But he smashed it, netting him $56bn in stock, the largest pay deal in history. You can’t view growth in abstract terms unrelated to real-world factors such as market size, but under the old deal Elon produced more market-cap growth in less time than the new deal requires.

Despite being twice ratified by a large majority of Tesla shareholders, that previous deal was struck down by the courts after a lawsuit by one shareholder who disagreed: the firm’s appeal began on 15 October. The new deal requires simple majority approval at Tesla’s AGM in Austin on 6 November: it will be carried, but risks similar subsequent legal challenge.

Elon’s last pay deal was also thought to be impossibly ambitious – but he got it

It’s still possible that Elon may flounce out if the pay deals are blocked or challenged: his most significant disincentive to doing so is the catastrophic effect it would have on the value of his current stake. Although it’s unlikely, it’s interesting to game-out what might happen if he were to quit. The share price would crash, Tesla would be valued more like a conventional car company – rather than a company that makes cars as well as energy storage products, solar energy generation products, and so on – and it would probably start to act accordingly.

A new CEO would fix the core car making business which Elon seems to have become bored by and forgotten. The first step would be to start replacement programmes for Tesla’s ageing line-up and plug the obvious holes, such as an SUV and the $25k ‘Model 2’ which Elon canned.

It was hoped that the Model 2, perhaps based on the Cybercab, would provide an entry point into Tesla ownership for first-time buyers unmoved by – or unable to afford – the Model 3. The competition at the more affordable end of the market has expanded hugely, with keenly priced offerings from Japan, Korea, Europe and China all snapping up buyers who could have been Tesla’s. Instead of a Model 2, Tesla has unveiled decontented lower-priced versions of the Model 3 and Model Y in some markets, to a largely unimpressed reception.

Product line-up has stalled in recent years. Is Musk the blocker?

That new CEO could well be JB Straubel, the ex-CTO who has returned to Tesla’s board, or any of the many senior staff who fell out with Elon or preferred to work in a slightly less intense environment and are now helping Tesla’s rivals. That process has accelerated recently, and most seem not to have been replaced. Daniel Ho, the director of vehicle programmes, went to Waymo last year. Battery boss Vineet Mehta left this year, as did powertrain chief Drew Baglino. Milan Kovac and Ashish Kumar, who led the robotics and AI on Optimus (the robot) respectively, also quit, the latter joining Meta. Rebecca Tinucci, in charge of the charger network, left for Uber.

The clear-out has further concentrated Elon’s influence over Tesla’s daily operations. It would make the share price correction all the more painful if he were to quit. But a flat hierarchy and some easy wins might tempt back one of the really senior ex-Tesla people who have gone to major rivals, such as Doug Field, now the chief EV, digital and design officer at Ford, or Sterling Anderson, who joined GM as chief product officer earlier this year and is tipped to replace Mary Barra as CEO, when she eventually retires.

Tesla under anyone other than Elon probably wouldn’t produce the armies of humanoid robots its investors hope it might, but it could produce a better, more complete range of EVs that would take the fight to Chinese rivals like BYD. And there’s a chance – just a chance – that we might get to witness that.