Shape of things that could have been…

Triumph’s in-house stylist, John Ashford, had big ideas when it came to expanding the TR7 into a whole range of different cars. Five decades on, he explains why it wasn’t to be

‘I wasn’t too heavily involved in the original design of the Triumph TR7 – my involvement really began on the Sprint version,’ says John Ashford, still Birmingham-based after a working lifetime at the heart of the British car industry.

‘That said, I did contribute the bonnet vents, depressing them into the metal rather than having them standing proud – I remember wanting to do it that way because it solved airflow issues over the windscreen.’

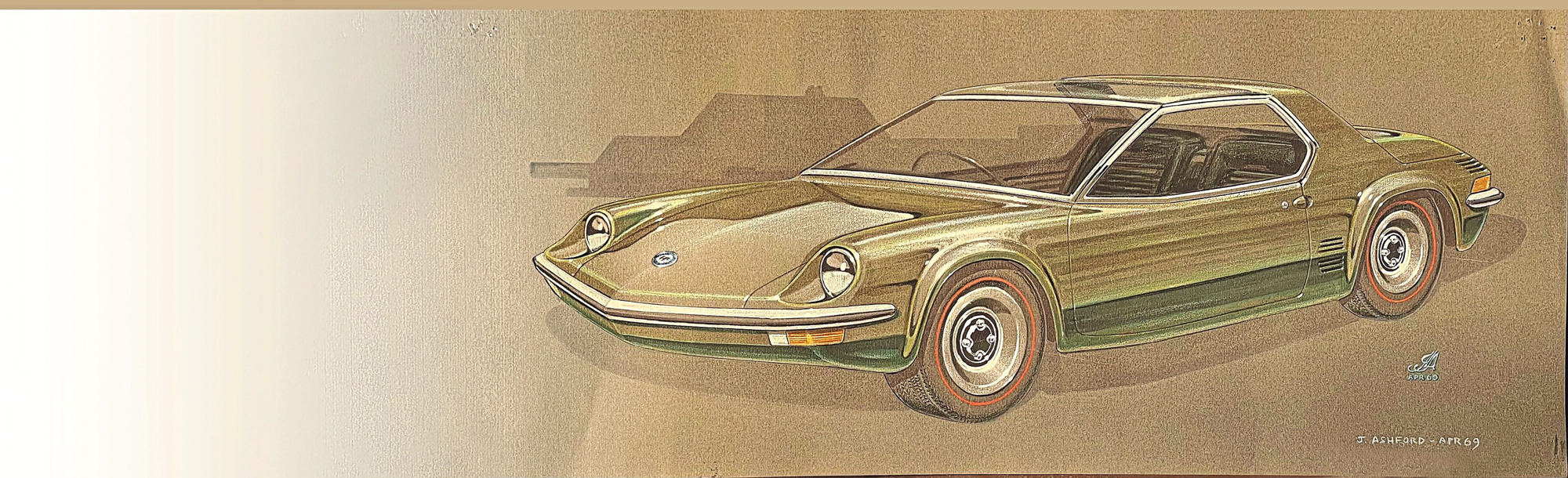

Tantalisingly Ashford reveals details of a mid-engined Triumph TR proposal he made in April 1969. Around the time of the TR7’s development, Triumph engineers were running a new Porsche 914 to evaluate it and while Ashford admits that it was never intended for production, it was certainly part of a maelstrom of ideas for the TR7 that circulated before BL management brought Harris Mann in.

‘At Triumph, we were working on our own version of the TR7 before Harris arrived,’ Ashford recalls. ‘At that time, it was a more straightforward development of the TR6 and didn’t have a wedge shape.

‘Two models were made – a Targa version and a closed coupé, like the Stag but with removable hard-top panels in its T-roof. At the front it looked a bit like how the original Volkswagen Golf would end up, with a rectangular grille with open headlamps at each end.

‘It was in existence when I joined Triumph in 1968 – they were working on it even as the TR6 was launched. It was done by Les Moore – whether Giovanni Michelotti was also involved, I don’t know – but people were talking about that particular design not going ahead even in 1968. In the end, BL management chose Harris Mann’s proposal – a clean break with the past, aimed squarely at the American market.

Ashford with the four-seater Triumph Lynx – a production-ready replacement for the Stag.

DENIED EXPANSION

‘But the TR7 range was originally intended to be much larger. There was actually a point where the basic eight-valve model would have been an MG, to replace the ’B,’ he explains. ‘One of the prototypes was built with MG badges but it became a Triumph during the development process.

‘I devised the Lynx four-seater fastback, and there was also a proposal to do a two-plus-two convertible, the Broadside, using Lynx panels. But because of problems with cash within British Leyland and with the Speke factory itself the whole Lynx and Broadside project was canned just at the stage when it was due to go into production.’

Ashford shares further details of how he intended the TR7 to evolve. With Harris Mann no longer involved, Ashford responded to criticism of the original car’s plunging swage line by removing it. His more barrel-sided creations owe more to David Bache’s contemporary Rover SD1, using its doorhandles and, in the case of the Broadside, its rear light clusters too.

Ashford thinks back to the mid-Seventies, and the plans at Longbridge regarding the future of BL’s various marques. ‘Talk at the time was that the Lynx would replace the Stag because its production run had been more limited than expected,’ he recalls. ‘Both Broadside and Lynx would be Stag replacements – the Stag was originally intended to be built in convertible and coupé forms, too, but in the end the hard-top version remained a one-off.

The TR7 2.0 was intended to replace the MGB – but Lord Stokes declined.

‘‘There was a real design challenge around open cars at the time because there was talk of withdrawing them completely from the US market’

‘There was going to be a range of engines, with Rover V8-engined versions as Stag replacements and a four-cylinder Lynx to replace the ’B GT. But at the time Lord Stokes decided that there was no future for the MG brand so all of BL’s future sports cars would be Triumphs.’

Unlike the TR7, though, BL was bold enough to devise the Broadside as a T-roofed, canvas-topped convertible. ‘There was a real design challenge around open cars at the time because there was talk of withdrawing them completely from the US market,’ says Ashford. ‘But while there were these ongoing safety concerns there was also a lot of doubt as to what should be done. The cars we were selling in the US market had enormous bumper overriders, which were the result of a lot of caution rather than meeting any exact legislation.

‘Things were very ambiguous during both TR7 and Lynx development. We’d always wanted to see a proper convertible TR7 – the TR6 had always been an open car – but Harris Mann’s design had started out as a metal-roofed coupé. The eventual convertible was an afterthought, albeit a popular one. Michelotti’s name was mentioned in connection with it but he used to do a lot of prototyping work for Triumph even if he hadn’t done the design work himself. He was trusted to realise cars in three dimensions.’

SPRINT FINISH

As well as creating the Lynx and Broadside, Ashford was also tasked with creating the TR7’s sense of identity, especially on the much-touted but short-lived 1977 16-valve Sprint-engined variant, which went from range mainstay to Group 4 rally homologation special thanks to BL cost-cutting rationalisation.

‘I created the “Sprint Stripe”, which ran the length of the car,’ says Ashford. ‘The requirement from Triumph was to take away emphasis from the TR7’s side-scallop, which wasn’t well-liked, as well as to differentiate the Sprint from the ordinary TR7.’

Ashford is credited with the body graphics used across the TR7 range, but latterly admits that the design wasn’t really his: ‘We always had our eye on the United States export market, and our importer, Bruce McWilliams, had a big say in Triumph’s marketing – the American point of view was very important to them.

‘The tape graphics on the TR7, including that open-font lettering, were actually designed by his wife, Gertrude ‘Jimmy’ McWilliams. Thing was, she actually worked as a graphic designer for General Motors at the time so they were passed to me and I had the job of working them into the TR7’s shape. I turned them italic in order to look right on the car.’

John Ashford’s design sketch dated April 1969 of a mid-engined TR proposal.

Like Harris Mann, John Ashford has misgivings about the initial engine choices for the TR7, although he explains why it ended up the way it did: ‘The problem with the Rover V8 was that it couldn’t be made in the quantity required for TR7 sales. It had been the same issue with the Stag. Longbridge talked about putting the Rover V8 in the Lynx for the US market, but it would have had the Sprint engine, too, primarily for the European market.

‘The Rover V8 was a natural fit for the car especially in the American export market. It was a GM engine originally, from the Buick Skylark, and when Triumph finally put it in the TR7 it modified it further, altering the carburation and fuel systems. The resulting TR8 was compared to the Corvette, but the Chevrolet was only really envisioned to sell in the US. I don’t think the TR7 was influenced by any other car.’