Growing old disgracefully

It’s 50 years since the last E-type was road registered; a V12 Series 3 that was very different from the original 1961 cars

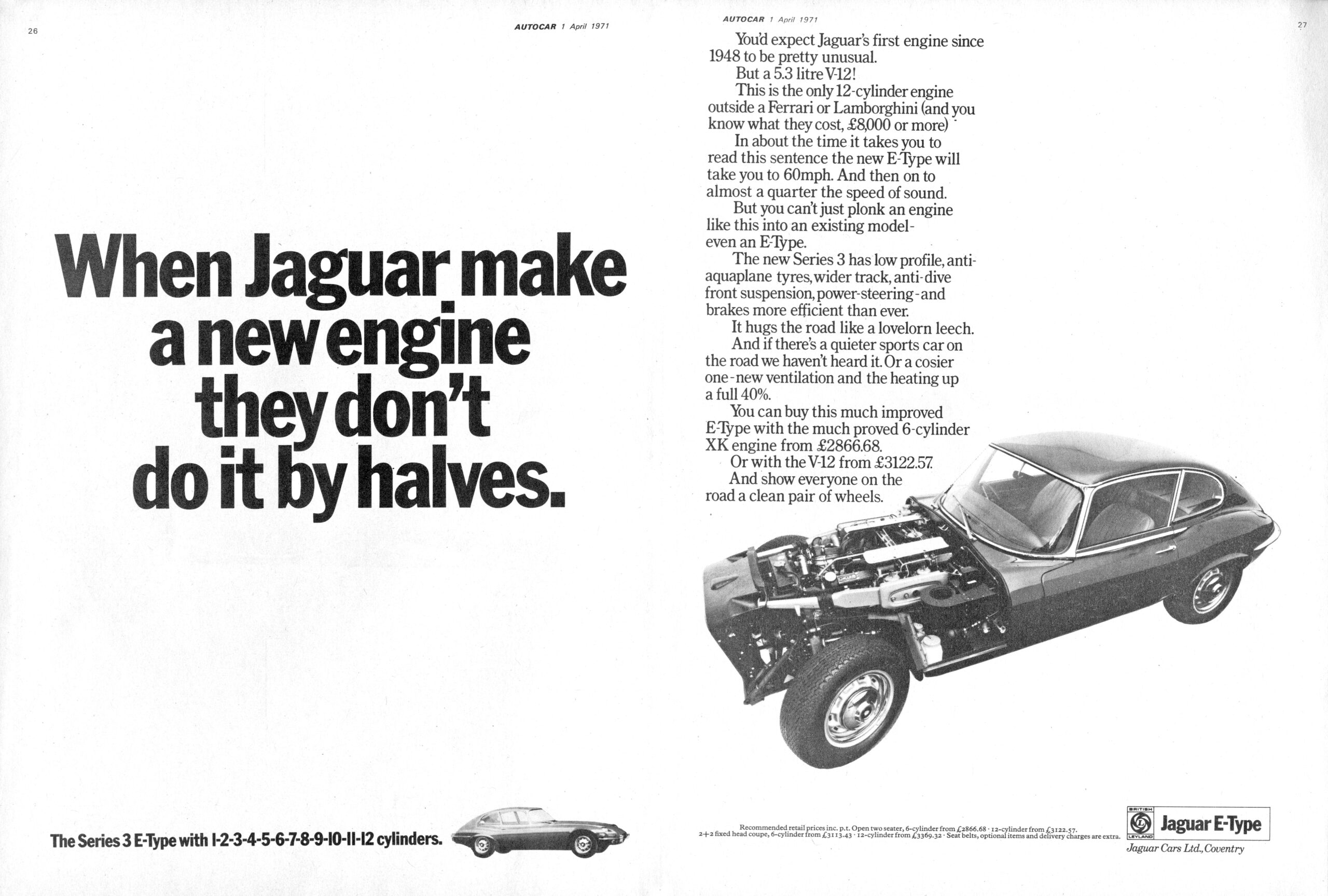

Jaguar finally introduced its long-planned V12 engine with the Series 3 E-type of March 1971. Paper figures of 314bhp at 6200rpm and 349lb ft at 3800rpm promised miracles when the outgoing Series 2 six-cylinder cars had a mere 246bhp, and sub-seven-second figures for the 0-60mph dash confirmed that the new E-type was still on top of its game. But, somehow, something was different.

Press reactions were muted on both sides of the Atlantic. America’s Road & Track summarised the V12 E-type as having ‘a magnificent engine in an outclassed body’, even though they found it ‘an exciting car to drive’. In Britain, Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson pulled his punches, admitting to being ‘slightly nonplussed but nevertheless impressed’ after a day’s test drive, despite commenting admiringly that the usable touring speed was 130-135mph.

Jenks had his own 4.2-litre roadster, and was well placed to make the comparison. The six-cylinder E-types had been urgent, almost crude machines but this new V12 was slick, smooth and unexpectedly refined. It seemed to take all the effort out of delivering stunning performance – and it made the E-type feel like a grand tourer rather than a sports car.

That impression was reinforced by the Series 3’s larger cabin, brought about by standardising both roadster and coupé models on the longer wheelbase of the 2+2 coupé. Axing the iconic short-wheelbase fixed-head coupé from the range did much to alter customer perceptions, too, while for roadster fans the longer doors changed the side profile too much. Though the car looked long and deliciously sleek, it had lost that animal-about-to-pounce look of its predecessors.

But we judge from today’s perspective. Now scrutinised by British Leyland accountants, Jaguar was struggling to contain costs. One wheelbase rather than two helped, and cars that appealed to the big Californian market were what the company needed.

Standardising power steering and introducing an automatic gearbox option for roadsters as well as coupés made quite clear what Jaguar’s thinking was. Besides, a manual gearbox was available for those who asked, and the fact that most customers chose the automatic speaks volumes about what the Series 3 was all about.

The fact is that it wasn’t the car that had gone soft but its target audience. Today, we look back on the V12 E-type through the haze of the 1973 Oil Crisis that hastened its end by making big-engined and thirsty cars unfashionable. But we can also take a different view, and recognise the V12 E-type’s enormous charm and character. Your challenge, should you choose to accept it, is to think of a more comfortable, rapid and prestigious sporting classic for all-round enjoyment today.

Bigger, wider and faster than ever – the S3 was a fitting swan song for the E-type.

FOUR YEARS OF CHANGE

There was not a lot of difference between the first and last Series 3 cars, even though Jaguar made the usual rash of minor specification changes right through the production run. There were more differences between models destined for the USA and those for other markets!

It’s worth highlighting just a few of the more visible changes, though. From August 1971, the V12’s cam covers no longer had the Jaguar name cast into them but made do with Jaguar stickers instead. The washer jets changed in January 1973, and then in February the original four-outlet tailpipe was replaced by one with just two outlets. An important change for the 1973 cars was the arrival of impact tubes for the bumpers on cars destined for the USA, accompanied by the first design of black rubber over-riders, which grew to meet legislative changes in 1974.

While all this was happening, there seems to be little doubt that the E-type’s buyer group was changing. The Series 3 was not a car to be bought for club racing at weekends and commuting during the week; it was too much of a sophisticated grand tourer for that. It was also no longer really new and exciting, the buyers who loved it for that having gradually faded away as the car grew older. Like an attractive actress, it moved on to more mature roles. As for the geographical location of its buyers, the vast majority were in North America, just as they had been since the E-type was introduced in 1961. Britain was the car’s second largest market, but it came a very poor second to the USA.

Most commentators cite the oil crisis of 1973-1974 as the primary reason for the demise of the V12 E-type. Cars that managed only 15mpg when enjoyed the way their makers intended became deeply unpopular in a very short space of time as higher fuel prices followed a period of threatened petrol rationing. It’s undoubtedly true that this made the V12 E-type next to unsaleable by mid-1974, but there were other clouds on the horizon that affected Jaguar’s thinking on the matter.

Those clouds can be blamed on the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)in the USA which, remember, was far and away the largest market for the E-type. The first one that floated into view called for a rollover bar to be fitted to the coupé models for 1974, which was an impossibility: there was simply no room in an already cramped cabin. So coupé production ended early, in September 1973, and roadster production was increased to compensate at Browns Lane.

The second NHTSA cloud was legislation planned for 1976 that was going to require compliance with a new rear-end barrier-crash test. The E-type’s rear-mounted fuel tank would not comply, and could not be made to comply without having recourse to a major re-design. So, Oil Crisis or no Oil Crisis, the days of the V12 Series 3 were well and truly numbered after 1973.

By 1974, the V12 E-type was up against some pretty formidable opposition, too. In Britain, the Jaguar name was still greatly revered, and foreign imports from the likes of Porsche and Mercedes-Benz did not have the same broad appeal. In the USA, however, the perception was very different.

US car makers could field nothing more exotic than the Chevrolet Corvette, which was a formidable machine that was not only quicker than the Jaguar but also considerably cheaper. But it was a Chevrolet, for Heaven’s sake, with about as much prestige as an Austin had in Britain. It was not a car to appeal to the wealthier inhabitants of the Californian sun belt.

There was far more prestige to be had from owning a foreign performance car. The Jaguar was just one option. Italy offered the Ferrari Dino 246GTS, and Germany’s temptations were the Porsche 911 and the Mercedes-Benz 450SL. The Ferrari cost about twice as much as the Jaguar, the Porsche in Targa form was 30% more expensive, and the Mercedes was over 70% more expensive. Those figures make the Jaguar look like a bargain, but the trouble was it was competing in a market sector where money is very often no object and prestige counts. Performance – on which the Jaguar scored highly – was less of a factor. How many wealthy Californian buyers were going to plump for the Jaguar instead of the prestige of the Ferrari or Mercedes-Benz names? Jaguar discovered the answer the hard way.

Counting to 12 apparently reinforces should how many cylinders there are in a dozen.

DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU’VE GOT ‘TIL IT’S GONE

Let’s be honest: the V12 E-type was dead in the water some time before its production was brought to an end. The last car may have been built on 14 June 1974, but it took the rest of the year to sell remaining stocks – and the last half-dozen cars did not find owners until 1975, the final car, HDU 555N being registered on 5 February , 50 years ago to the day. So by the end of the production run, the glamour of the car once (and subsequently) hailed as the most beautiful ever built had well and truly faded. However, it didn’t take too long before views began to change. When the XJ-S was revealed in 1975 to take the E-type’s place in the Jaguar range, it turned out not to be the same type of car at all (and, in fairness, Jaguar had never intended it as a direct replacement). At that point, the rose-tinted glasses came out and people began to lament the passing of a legend, even though they hadn’t bothered to visit their local showrooms to buy one when the cars were available new. Since then, interest in the V12 E-type has grown exponentially, and with that growth of interest has come a huge rise in asking prices.

You can certainly argue a strong case for why the V12 E-Type is so much in demand now. It combines most of the Sixties charm and character of the original car with a much more modern and refined drivetrain that makes it a lot easier to drive. And the extra cabin room offered by the longer wheelbase makes it more comfortable too, as long as you don’t mind the traditional E-type faults of cramped footwells and switchgear that has to be memorised even if it does look impressively like that from a fighter jet. The V12 E-type, then, may not be a car for Jaguar purists, but as a classic for wafting about in decent weather, a roadster model is close to unbeatable.

HDU 555N, the final E-type built, has been with the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust for the past 40 years.

THE STORY BEHIND THE FINAL E-TYPE

The last E-type was built on 12 June 1974 but wasn’t registered until 5 February 1975, 50 years ago. The Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust (JDHT)’s vehicle collection manager, Neil Campbell, explains: ‘Jaguar has always been good at choosing number plates for their last of line cars. ‘DU’ is a Coventry number and “555” is a nice number.’

Jaguar had always intended to retain the car, given its significance as the last E-type, and transferred it to the Heritage Trust when it was formed in September 1983. HDU was part of a run of 50 cars commemorating the end of the E-type, all of which wear a special plaque bearing Sir William Lyons’ signature and are painted black, except for the second to last car, which was supplied to a private Jaguar collector in British Racing Green. Says Neil: ‘There are things missing off this car that the other final run of 50 had. It doesn’t have fog lights or reversing lights and no wing mirrors. The story is, whether it’s a myth or not, that they started to run out of bits as they were building those last 50 cars. It’s said that they started off with two reversing lights, then they ended up with one, and the last ones didn’t have any. It is really quite believable knowing how Jaguar was back then!’

‘It’s had a bit of work on it here and there. The interior has been re-trimmed and it’s been painted but it’s just normal wear and tear really.

‘We like to use our cars and for them to get out and about. HDU 555N did quite a bit last year; it was 50 years of Coventry Ring Road so the BBC used it for a drive where we discussed the history of Coventry, the Ring Road and car manufacturing in the area. It’s always MoT’d and taxed.’