Stars of 1955 – 70 years on

In 1955 these were the most exciting new cars on the road. Seven decades on, does their appeal live up to their reputations – and do they make good classic buys?

Clubs and coffee shops reverberated to Bill Haley and the exciting new sound of rock’n’roll. ITV was launched, Christopher Cockerell patented the hovercraft and Gary Sobers made his test cricket debut for the West Indies. Bird’s Eye invented the fish finger. Steve McQueen appeared on TV for the first time, and we said goodbye to James Dean, Einstein and Alexander Fleming. Ill-health forced Churchill to leave Number 10 at the age of 80. Motor sport was rocked by the worst accident it had ever seen, at Le Mans, then celebrated when Stirling Moss became the first English winner of the British Grand Prix.

It was 1955, and the motor industry was booming. The production lines that had been turned over to war production just a few years before were rebuilt and re-equipped, and were churning out new machinery to replace pre-war cars at home and abroad. In Britain, across Europe and further afield, car makers were gearing up for new models and new markets. Economies were thriving and car buyers were queueing up for the latest models.

Seven decades on, we’ve gathered together the new kids on the 1955 block amid the time-warp atmosphere of Bicester Heritage to see how they fare as 21st-century classics.

We have Bentley’s S1, which carried over much that was good about the R-type, and the first V8 version of Chevrolet’s stylish Corvette. Meanwhile, bold new ideas came from MG, with its overdue new-generation MGA, the Jaguar 2.4 and Alfa Romeo Giulietta saloons with their new-fangled monocoque construction and modern twin-cam engines, and the outlandish Citroën DS19.

Citroën DS19

The Citroën had been in development since the Thirties. ‘Projet D’ was finally unveiled as the DS19 at the ’55 Paris salon, where it shocked crowds with its remarkable shape and advanced hydraulic systems. Six decades later it’s still one of the most extraordinary vehicles on the road.

Even before you step inside it, the DS seems alien – a flying saucer from another world that hovers a few inches off the ground awaiting instructions from some unseen mothership. Even after all this time it’s still a challenging shape, with its visual mass concentrated around the A-pillar and tapering aggressively towards the tail both in profile and plan.

On Patrice Rowell’s car the sober black bodywork gives no clue to what lies inside – leopard-like fabric that swathes the seats and doors with startling patterned orange.

It’s not the only thing about the interior that’s unsettling, either. There’s the odd single-spoke steering wheel, on the wrong side for UK use, and the big rubber button on the floor that operates the brakes. Glance in the rear-view mirror and there’s the curious sight of a venetian blind in the rear window, a rare French option. And there’s no clutch pedal.

The DS19’s hydraulic system not only powered the brakes, suspension and steering, but it extended as far as the transmission. Click the dainty gearlever that sprouts from the right-hand side of the steering column into a new ratio and the hydraulics mesh the gears and operate the clutch for you. It can be a bit jerky from rest so manoeuvring at walking pace in a tight spot calls for experience and a steady nerve, but once on the move it works remarkably well. So do the brakes, with their inboard front discs, though that pressure-sensitive button takes some getting used to. The DS suspension soaks up bumps with a sophistication that’s still impressive today – the calm and cossetting ride must have seemed tantamount to witchcraft in 1955.

It’s astonishing on so many levels, but the DS19 is brought back to reality by its engine, a refugee from the Traction Avant of the Thirties. The long-stroke four is tough and torquey, but it grumbles away in the nose, upsetting the calm, quiet vibe of the rest of the car. Sweeter short-stroke engines were introduced in the Sixties, followed by bigger-capacity units with more power.

However, it’s a shame the flat-six mooted for the DS from the start never reached production. If it had, the combination of smooth power and the DS suspension might have made it a formidable rally machine. As it was, some successes in long-distance events (and Monte victories in 1959 and 1966, even if the latter was dubious) were all it could muster.

You can pick up a DS from £8000 or so, but at this level even respectable-looking cars will hide a multitude of horrors. Good DS21s and 23s start around £20,000 and a really tidy early one will set you back around £40,000, and unless you’re keen to take on the formidable challenge of a full restoration you’re better off buying the best you can afford. Rust in the chassis and ‘caisson’ body frame is the main concern, as it can develop without any visible signs on the unstressed outer panels. Mechanically the DS is robust, and if well-maintained the hydraulics rarely give trouble.

Today the early DS appeals for the outlandishness and purity of its concept. If that amazing shape and the extraordinary, quirky road manners appeal, you won’t regret it.

Owning a Citroën DS19

‘I’m half French and fascinated by French stuff,’ says Patrice Rowell. I do vintage car restorations, and part of the appeal of the DS for me is the connection down the line to the vintage side – Gabriele Voisin trained André Lefèbvre, who was the chief designer of the DS. He was given a free hand to design these. They’re beautiful.

‘I wanted a restoration project, and the challenge of restoring the hydraulics. This car was complete but in pieces – it was acquired by a museum and they had stripped it completely. Restoration is complicated – challenging and enjoyable. I’ve had it five years and it’s been relatively trouble-free.

‘Driving it is interesting. You don’t know whether you are driving it or it’s driving you, because the semi-automatic transmission takes over the throttle. Get one that’s good mechanically and similarly so chassis-wise. You need to speak to an expert like Jamie at DS Workshop. The early ones are the purest, but if you want to use one on a daily basis you need a DS21. They are much more refined, while DS19s are slightly underpowered.’

Specifications

Engine 1911cc in-line four-cylinder, ohv, Zenith 24/30EEAC carburettor

Power and torque 75bhp @ 4500rpm, 101lb ft @ 3000rpm

Transmission Four-speed semi-automatic, front-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: independent, leading arms, hydropneumatic springs/dampers, anti-roll bar

Rear: independent, trailing arms, hydropneumatic springs/dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes Inboard discs front, drums rear, powered hydraulic operation

Weight 1237kg (2727lb)

Performance Top speed: 88mph; 0-60mph: 15sec

Fuel consumption 24-30mpg

Length 4800mm

Width 1790mm

Cost new £1726

MGA 1500

If the DS was a leap into the unknown for Citroën, which had some previous in its use of innovative engineering, then the MGA was almost as big a step forward for MG after years of old-fashioned designs. The streamlined body shape came first, designed by Syd Enever for George Philips’ TD-based Le Mans car of 1951.

When parent company BMC eventually gave the green light for the new car, the 1.5-litre BMC B-series unit already used in the Magnette saloon was dropped into a new chassis with wider-spaced side members, so the seat position could be lowered. Three aluminium-bodied prototypes were entered into the ill-fated Le Mans race in 1955, one crashing but the other two finishing fifth and sixth in their class, a creditable result. In its production version the new MG was such a departure from what had gone before that Abingdon decided to abandon its existing two-letter model nomenclature and start again, so the car was christened MGA and revealed at European motor shows in the autumn of 1955.

It’s a spectacularly pretty car, with a striking lack of external decoration. Roadsters like Paul Anderton’s Old English White car even do without exterior door handles so you reach inside and pull the cord hidden at the top of the door pocket. The big four-spoke wheel gets in the way as you climb down into the cockpit, but the driving position is comfortable. There’s a short, central gearlever that slots easily into first and the MGA is away with a purposeful bark from the SU-fed B-series. It’s an engine that never sounds happy being revved hard; instead it’s best to stick to the mid-range where there’s plenty of torque available and it’s easy to make fuss-free progress. In corners you quickly reach the limit of grip, but the MGA drifts gently and predictably, just like a sports car should. The long-distance road rallies of the day suited it well, and works MGAs were regular class winners.

A decent early roadster such as this will set you back around £25,000. Basket cases are half that, while the best will be £30,000 or more. Coupés are worth a little less. The MGA 1600 built from 1959 onwards has similar values, while the rare Twin Cam costs upwards of £40,000.

The B-series engines are tough but watch for oil leaks from the simple scroll-type rear oil seal, which can be costly to fix. Cracked cylinder heads and blown head gaskets are also concerns, so check for signs that the engine has been losing water. The most costly concern is the bodywork – rust attacks sills, A-pillars, wings and boot floor, while the alloy-skinned bonnet, bootlid and doors suffer from electrolytic corrosion. Fortunately, repair panels are available. Most MGAs were sold overseas but conversion to right-hand drive is relatively simple, though UK-spec steering racks are pricey.

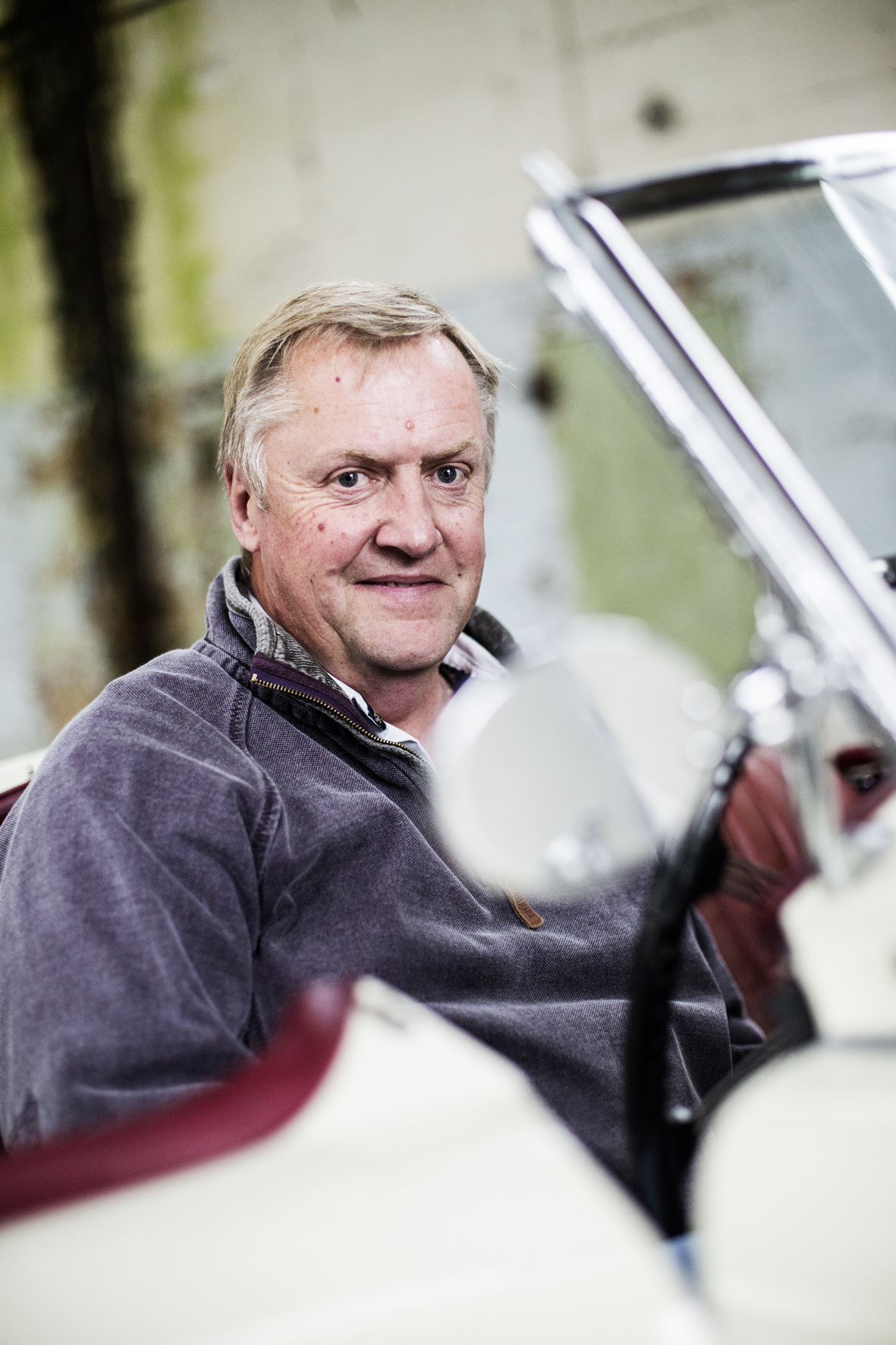

Owning an MGA 1500

‘I’ve really got a thing about British sports cars – I’ve got a Triumph TR6 too, says Paul Anderton. I’ve always liked MGAs, and I particularly wanted a roadster.

‘They say there isn’t a great deal of difference between the 1500 and 1600. I looked at half a dozen but this one was in particularly good condition. The body is as good as it gets – the panel gaps weren’t great when they were new. It’s a very simple car, and mechanically I can do things myself.

‘Most of the MGs went abroad and this was originally a left-hand-drive example. It was re-imported in about 1999 and converted to right-hand-drive specification. I eventually found the guy who imported it, who gave me lots of fantastic old photographs.

‘I’ve had it a couple of years and it gets used for high days and holidays. It’s nice for a run round the lanes. It’s really just a bit of fun. Would you want to go to the south of France in it? No, you wouldn’t. It’s screaming out for an overdrive or a fifth gear, and it’s only got drum brakes on the front. If I drove it more regularly that’s probably one of the things I would upgrade.’

Specifications

Engine 1489cc in-line four-cylinder, ohv, twin SU H4 carburettors

Power and torque 69bhp @ 4700rpm, 77lb ft @ 3500rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: wishbones, coil springs, lever-arm dampers.

Rear: live axle, leaf springs, lever-arm dampers

Brakes Hydraulic drums

Weight 890kg (1962lb)

Performance Top speed: 98mph; 0-60mph: 11sec

Fuel consumption 30-35mpg

Length 3962mm

Width 1473mm

Cost new £844

Chevrolet Corvette v8

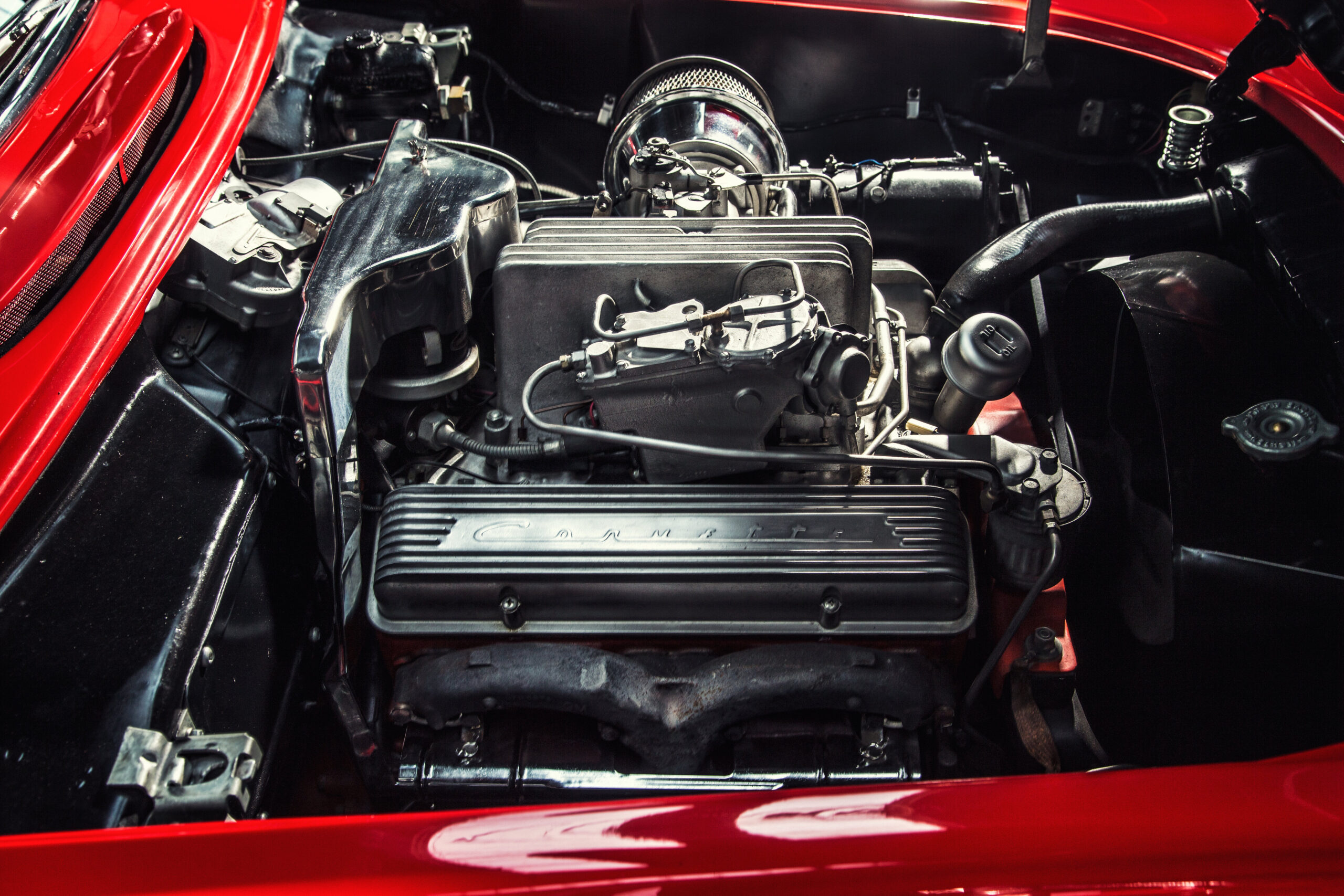

Across the pond they were building a very different kind of sports car. Chevrolet introduced its Corvette in six-cylinder form in 1953, and in 1955 it got the engine that turned it from a mildly interesting boulevard cruiser into a genuine hot rod.

The 4.3-litre (265ci) small-block V8 developed a claimed 210hp; quite a jump from the 150bhp of the ‘Blue Flame Special’ in-line six in the first Corvettes. It didn’t take much work to get a genuine 150mph out of these cars – they were no longer trailing behind the Jaguar XKs their styling was intended to ape but now comprehensively besting them. And the effect of the new engine went further than just adding straight-line speed. The V8 was 41lb lighter than the six – which was descended from a truck engine – and it was shorter and lower, which meant it could be mounted further back in the engine bay, carrying its weight lower in the car. As a result the revitalised Corvette wasn’t just quicker, it also handled far better.

It looked a lot more sophisticated too. Chevrolet’s stylists moved on from using the XK120 as their muse and latched on to the Mercedes 300 SL roadster instead, adding styling cues like the stand-up headlamps and twin bonnet bulges to the glassfibre body. The scalloped sides – often painted a contrasting colour – were a late 1955 introduction for the ’56 model year, and the Rochester Ramjet fuel injection and four-speed manual gearbox on this car didn’t arrive until early 1957. Chevrolet claimed the ‘fuelie’ Corvette had 283bhp, and it would beat six seconds for the 0-60mph dash. It’s little wonder that the V8 Corvette came to dominate SCCA production-class racing in the US, and a Cunningham-entered Corvette finished eighth at Le Mans in 1960.

It feels every bit as quick as its reputation. Getting the Corvette off the line smartly isn’t easy, particularly if the surface is damp. It’s all too easy to squander the power by spinning the Goodrich crossply tyres, which howl in protest. Once the rubber has hooked up with the road surface the Corvette squats on its back axle and rockets away, the V8 bellowing into the slipstream through the rear-exit pipes. The close-set steering wheel forces a very vintage driving position, which doesn’t make tidy cornering easy.

Corvettes like this are rare in the UK, so for more choice and better bargains buyers need to look Stateside. They’re generally robust cars, but it’s important to check for signs of corrosion or crash repair to the chassis.

Beyond overall condition, it’s originality and rarity of options (such as fuel injection and a hardtop) that drive values. Cars with manual gearboxes and bright colours fetch the highest prices, though the values of the 1955-57 single-headlamp cars lag about 10 per cent behind the 1957-on, twin-lamp Corvettes. These early cars start from around £35,000 (less in the US, where there are more to choose from) and the best change hands for around £80,000.

Owning a Chevrolet Corvette

‘My sons and I collect Fifties to Seventies cars,’ says Les Harris, ‘anything that is different or holds a special memory for me. We have always been interested in classic Americans and the ’57 Vette in red/white was our ideal. The car is immaculate with a lot of history, having being used on some films.

‘We take it to shows and I occasionally use it for weddings for friends alongside my ’57 Chevy Bel Air estate. It has never been any trouble as long as it is regularly started and given a little exercise.

‘These cars are iconic and when I take it out there is always tremendous interest. They are associated with the ‘good old days’ of fun and freedom as portrayed in the films of that era. It is a privilege to own one.

‘I’d advise a buyer to make sure the car has been correctly restored and looked after. Parts are still, I believe, quite easy to obtain from the States. It is fitted with crossply tyres as per original spec and so isn’t easy to control on the road, especially in damp conditions. I’m trying to find some radials, which will make the handling much better.’

Specifications

Engine 4639cc V8, ohv, Carter WCFB carburettor or Rochester Ram Jet fuel injection

Power and torque 195-283bhp @ 5000-6200rpm, 260-290lb ft @ 3000-4400rpm

Transmission Three or four-speed manual or two-speed automatic, rear-wheel drive

Steering Recirculating ball

Suspension Front: independent, wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

Rear: live axle, leaf springs, telescopic dampers

Brakes Hydraulic drums

Weight 1323kg (2910lb)

Performance Top speed: 133mph; 0-60mph: 6sec

Fuel consumption 15mpg

Length 4510mm

Width 1855mm

Cost new £1499

Bentley S-type

Like the Corvette V8, Bentley’s S-type came by a process of evolution rather than revolution. The styling had been refined in a push-pull process between John Blatchley at Rolls-Royce, who drew up the ‘standard steel’ Rolls and Bentley saloons of late Forties and early Fifties, and Stanley Watts at HJ Mulliner who designed the fastback Continental coupés. The straight-six F-head engine could trace its lineage all the way back to the 3.2-litre Rolls-Royce 20hp of 1922, and in the S-type it was bored out to 4.9 litres and given a new six-port cylinder head and revised intake manifold.

The chassis was new and 50 per cent stiffer than before, but followed the same basic pattern that Bentley had used since the Mark V in 1939. The suspension had changes to the geometry of the front wishbones and a better location for the live rear axle. A curious braking system had hydraulic operation all round, but with an extra mechanical linkage to the rear brakes, said to provide greater feel at low speeds, and a gearbox-driven servo.

Swing open the heavy door and step inside the S-type and it’s the sheer quality that immediately impresses. Everything inside the Bentley is made from the highest-grade materials, from the deep-pile carpet to the hand-crafted veneered dashboard that carries a circular panel in the centre for the ignition key. Give the key a twist and after the whir of the starter dies away there’s hardly any indication that the engine is running – only the quiver of the needle on the upside-down rev counter gives the game away. All but a handful of S-types were fitted with automatic transmissions (there was a short-lived manual option for the Continental) with the lever mounted on the column behind the enormous three-spoke steering wheel. Slot into drive and squeeze the accelerator pedal and the big Bentley oozes into motion, with still only the barest whisper from the engine room. The steering has more than four turns between locks so plenty of arm-twirling is needed when parking, but even at walking pace it’s light and easy to handle. Prod the throttle harder and the transmission slurs into a lower gear, and finally you can hear the genteel hum of the engine at work.

Despite the engine’s capacity, and the higher compression ratio that was part of the Continental specification, acceleration is never more than brisk – but these were genuine 120mph cars that could cruise in three figures all day long.

The engines and gearboxes in the S-type have proved to be robust, though a detailed service history is important and it’s wise to check for good oil pressure. Power steering, standard on later cars, is desirable. Key corrosion points are the body to chassis mounts, particularly at the rear near the battery carrier, and the sills and lower body panels. Look out for shabby trim and woodwork too: it’s all restorable, but the costs are high.

A saloon needing work will start from around £15,000, with good examples in the £25,000-£50,000 range. Continentals start at £140,000 and rise rapidly if condition and history warrants.

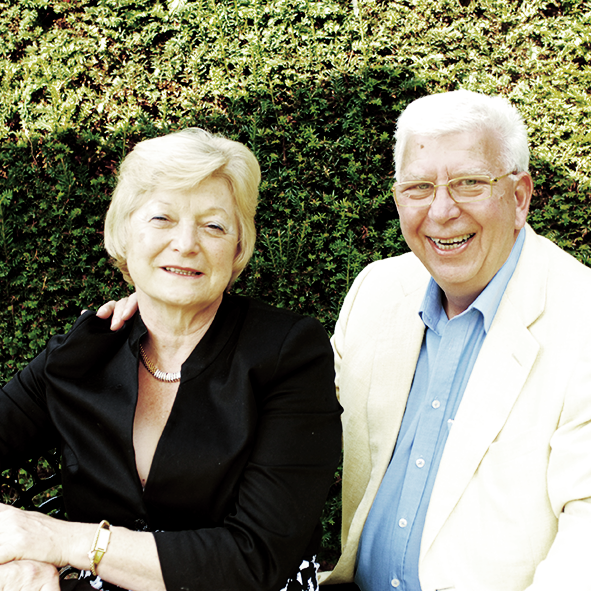

Owning a Bentley S1

I’ve always liked classics – I’ve had a Daimler V8-250 since 1978,’ says Ian Owen. ‘I’d always liked the fastback shape of these and after I sold a business I could buy one. It was delivered new to Switzerland so the speedometer is in kilometres per hour. It was in very good condition and I liked the colour scheme. I took it to the Bentley Drivers’ Club concours and it won the Commended title. I brought it back the next year and it was highly commended again. The paintwork had always slightly bothered me and wasn’t quite Tudor Grey, so the body was taken back to bare metal and it’s been fully painted, and the chrome’s been redone. I also put a dynamo on it and took the aircon off to take it back to standard.

‘I’ve got another that’s been prepared for continental touring. It will happily cruise along. There’s some wind noise at motorway speeds – probably from the mirrors, which aren’t original. The brakes are servo-assisted off the back of the gearbox – a typical Rolls-Royce feature. They don’t work when you are almost stationary.’

Specifications

Engine 4887cc in-line six, inlet over exhaust valves, twin SU HD6 carburettors

Power and torque About 155-197bhp @ 4000-4500rpm, 330lb ft @ 2500rpm

Transmission Three- or four-speed automatic, rear-wheel drive

Steering Worm and roller

Suspension Front: independent, wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

Rear: live axle, telescopic dampers, leaf springs

Brakes Hydraulic drums

Weight 1880-1925kg (4145-4235lb)

Performance Top speed: 103-119mph; 0-60mph: 12-14sec

Fuel consumption 13mpg

Length 5385mm

Width 1899mm

Cost new £1838

Alfa Giulietta 750-series

While the Bentley appeared first as a saloon and then later as a coupé, Alfa Romeo trod the reverse path with its new small car, the Giulietta. The money for the car’s development was raised by selling debentures, investors being attracted by regular interest payments and the prospect of 200 of the new cars being given away in a prize draw for debenture holders.

The saloon had originally been slated to appear in 1953, but it took longer than expected to tool up for the new monocoque body. Bertone was hurriedly engaged to piece together the Sprint coupé, using saloon mechanicals and a new body – which some said was designed in just 10 days. The Sprint was ready for the Turin show in 1954, and it bought Alfa enough time to get the saloon ready.

Inevitably it lacks the rakish good looks of the Bertone coupé, but the Giulietta Berlina saloon is a tidy shape that owes much to its big brother, the 1900. The influence of the bigger car is particularly obvious at the front, with its imposing Alfa ‘moustache’ grilles. Inside, it’s classic sporting Alfa with a Fifties American twist provided by the big Bakelite steering wheel with its chrome horn ring, half-moon speedo, bench seat and column gearchange.

The column change is surprisingly good. The secret to it is not to try too hard – first and second are easy to find but the third/fourth plane is harder to slot accurately until you realise the lever naturally returns there under spring pressure, so a light touch on the lever and a nudge up or down is all that’s required. The slick four-speed manual gearbox is connected to a sweet 1290cc all-alloy four with twin camshafts that delivers just 53bhp, but responds with such relish that it imbues the whole car with an infectious enthusiasm. Show the Giulietta a corner and that enthusiastic demeanour comes to the fore again – the body rolls alarmingly, but the little Alfa turns in keenly even at silly entry speeds and just scurries around, leaving you kicking yourself for not going even faster. It’s easy to see why it was an effective rally car in TI form, finishing second and third in the Alpine Rally of 1958 behind the winning Giulietta Sprint.

Mechanically they are strong, though spares can be trickier to source than you might imagine because the engine, gearbox and suspension on these early 750-series cars are all different to the later 101-series and parts aren’t always interchangeable. Rust is the bigger problem, attacking the doors, floor and sills. Repair panels aren’t available, but new-old-stock parts do still sometimes turn up – the Giulietta Register suggests buying parts direct from Italy. Restoration costs will always exceed the car’s value, so it’s really important to start with the best possible example.

The Giulietta is such a hoot to drive it’s a shame so few made it out of Italy – and that so few survive.

Owning an Alfa Giulietta

‘I looked for this car for five years,’ says Tom Gibb, ‘and the biggest problem I had was finding one – most have been turned into race or rally cars. As with a lot of old Italian cars you’ve got to be careful of the metalwork – wheelarches particularly. This one was bought by a collector I know and I said I wanted the first crack at it if he sold it. It’s largely original, and the oldest Giulietta Berlina in the UK.

‘Mechanically it’s all very simple and easy to sort out if it goes wrong. The engine is a 1300 750-series twin-cam, the same block and head as the Spiders but with a small Solex carburettor and restrictive intake manifold – it probably has the least amount of power they ever got from the twin-cam engine. The fuel economy is extraordinary – I only have to fill it up every two months. If you want to get more power out of it you can do, but that’s not what it’s about.

‘Most bits are available, though trim is difficult. Tony at Alfa Stop is brilliant – he can find most parts.

I’ll never sell it. I’ve had lots of cars, but this one’s going all the way with me. I’ve also got a ’67 Giulia Super and had a ’67 Spider I restored from the ground up.’

Specifications

Engine 1290cc in-line four, dohc, Solex C.32 BI carburettor

Power and torque 53bhp @ 5200rpm, 69lb ft @ 3000rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Cam and peg steering box

Suspension Front: independent, wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

Rear: live axle, coil springs, radius arms, telescopic dampers, A-bracket

Brakes Hydraulic drums

Weight 876kg (1931lb)

Performance Top speed: 88mph; 0-60mph: 19sec

Fuel consumption 30mpg

Length 3990mm

Width 1550mm

Cost new £1532

Jaguar 2.4 MkI

Jaguar 2.4s don’t come much better than Michael Byng’s concours winner, which shows just how stunning this compact, monocoque-construction saloon must have looked when it was brand-new. With spats over the rear wheels, as it was originally intended to have, the 2.4 has a deceptively clean and simple shape with a timeless appeal. Jaguar considered a four-cylinder version of the XK engine for this car, but thankfully opted for a short-stroke version of the existing in-line six instead. Turn the key in the wooden dash and it fires easily, settling to a quiet, vibration-free idle. It’s probably the smoothest of all the XK engines, with a creamy delivery and a musical engine note, which makes it sound more powerful than it really is. The 112bhp it offers inevitably can’t compare with the outputs of its 3.4-litre and 3.8-litre brethren, but thanks to prodigious low-speed torque it will keep up with modern traffic. The Moss gearbox isn’t the slickest but engine and road noise levels are low and, despite the live axle at the back, the ride quality is excellent. Low-geared steering means you need big arcs of the four-spoke wheel in corners, but the Jaguar hunts out apexes with a precision few saloon cars could match in the Fifties.

Add the power of the 3.4-litre XK engine and you got a formidable sporting saloon. It soon came to dominate saloon car racing grids, and very nearly took Tommy Sopwith to the very first British Saloon Car Championship title in 1958 – equal on points with Jack Sears at the end of the season, he lost a 10-lap tiebreaker by little more than one second.

It was in MkIs that stars of Grand Prix and sports car racing like Stirling Moss, Jack Brabham, Roy Salvadori and Ivor Bueb regularly rubbed door handles in the later Fifties. Mike Hawthorn thoroughly enjoyed his own much-modified 3.4 MkI, but it was that car that he crashed and died in just a few months after securing his F1 World Championship in 1959.

The MkI was replaced that year by the Mk2, and although the later cars are sometimes seen as more desirable the MkI is rarer, so values work out about the same. A complete car in need of restoration comes in around £8500, with good useable machines going for between £15,000 and £27,000. Show winning examples can command prices of £40,000 or more. Standard, original cars are the most sought after – modifications tend to reduce the value rather than increase it. Parts availability is excellent but restoration costs are substantial, so it’s another car where it pays to find one that has already benefited from plenty of attention.

Owning a Jaguar MkI

‘I’ve had my Jaguar MkI about eight years,’ says Michael Byng. ‘I like original cars, and I really wanted a MkI with wheel spats.

‘This one had to be completely restored, because the bottom eight inches of the body had gone.

Lee Ridley did it – he’s a brilliant bloke. It’s Jaguar Pastel Blue, which wasn’t a popular colour when it was new.

‘It’s a 2.4-litre engine. We took the head off and gave it a clean, and it was fine. All the 2.4 ancillary bits are difficult to get now.

‘It took six years to finish the air box properly – and the toolkits are like hen’s teeth. I’ve done 90mph or 100mph in this, but you have to plan for the braking because it has drums on the front. You have to use the gears to slow down.

‘We’ve done several Jaguar Drivers’ Club runs in it, and I’ve never encountered any trouble with it on those events. I’ve got a very friendly garage in Membury that helps us a lot. I’m lucky enough to have a collection of Jaguars, but my MkIX and this are my favourites. I’m looking for a 3.4 now – I’m going to restore it myself.’

Specifications

Engine 2483cc in-line six, dohc, twin Solex B.32 PBI-5 carburettors

Power and torque 112bhp @ 5750rpm, 140lb ft @ 2000rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Recirculating ball

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, lever-arm dampers, anti-roll bar.

Rear: cantilever leaf springs, lever-arm dampers and Panhard rod

Brakes Hydraulic drums front and rear

Weight 1374kg (3029lb)

Performance Top speed: 102mph; 0-60mph: 15sec

Fuel consumption 24mpg

Length 4591mm

Width 1695mm

Cost new £1532

Boom selection

These six cars represent the state of the art back in ’55, and the differences between them underline the freedom car makers had in the immediate post-war years to innovate. Our six of the best include separate chassis and unitary construction, steel and glassfibre bodies, and everything from pedestrian pushrod fours to the latest in short-stroke V8s.

Which is best depends on what you want from a car, but if it’s 1955’s most future-chasing design it has to be the Citroën. Some of its innovations are only just becoming commonplace today.

Thanks to: The Classic Corvette Club UK (corvetteclub.org.uk), The Giulietta Register (giulietta.com), MG Car Club MGA Register (mgcc.co.uk/mga-register), Jaguar Drivers’ Club Mark I and 2 Register (jaguardriver.co.uk/html/themk12register.html), Historit (historit.co.uk), DS Workshop (dsworkshop.co.uk), Bentley Drivers’ Club (bdcl.org)