From the court room – what it’s like to attend Diddy’s trial

Megan Agnew, senior features writer at the Times and the Sunday Times, is based in New York.

Words by Megan Agnew

Cassandra “Cassie” Ventura fidgeted in the witness box before each day of questioning, nervously rearranging the bottles of water on the stand in front of her, fiddling with her hair, rubbing her stomach, looking down at her eight-and-a-half month pregnant body.

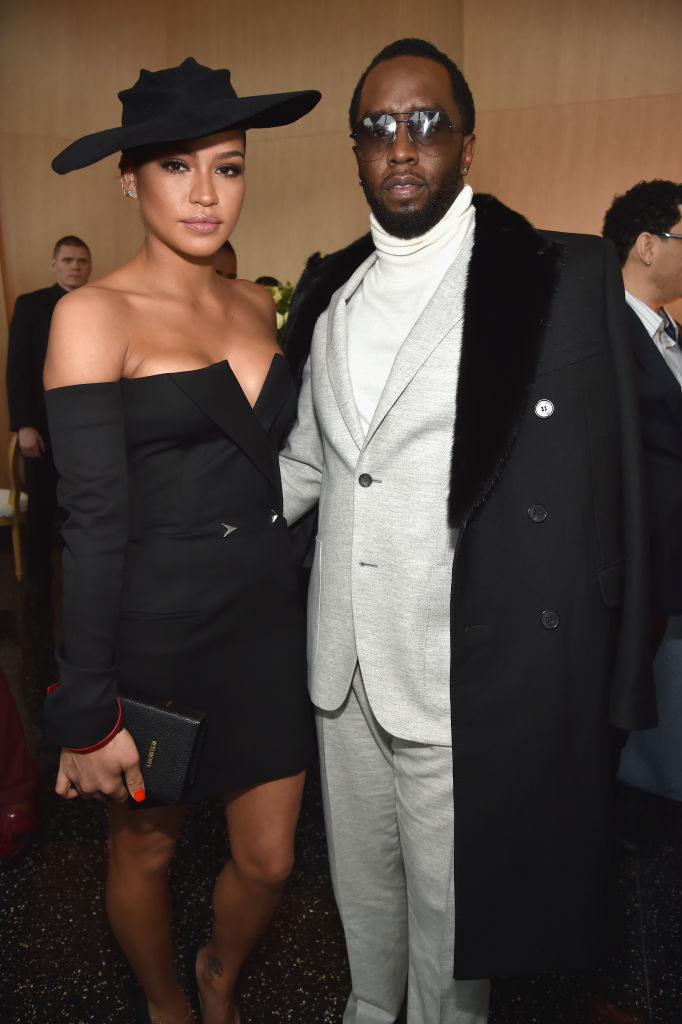

Just meters away from the 38-year-old popstar was her former partner of 11 years, hip-hop mogul Sean Combs, 55, looking towards her, leaning far back in his chair, hands arched in front of him, the benches in court behind him packed-out with his various children, relatives and his beloved mother.

Combs – or P-Diddy or Puff Daddy or Brother Love – was arrested in September 2024 and charged with racketeering conspiracy, sex trafficking and transportation to engage in prostitution, to which he pleaded not guilty. The trial, which started in a Manhattan federal courtroom on May 5, will last around eight weeks. He faces life in prison.

The prosecution is in the process of calling up dozens of witnesses – former friends and employees, law enforcement officers and sex workers – in an attempt to prove that Combs’ business empire (at one point worth over $1 billion) was in fact a “criminal enterprise” which he used to facilitate abuse and commercial sex. Combs’ defense team argued that he was an abuser, but that “domestic violence is not sex trafficking”.

Ventura was one of the prosecution’s primary witnesses and, in an extraordinary act of bravery, the only one of four alleged victims to choose not be anonymised. She took the stand for four days straight, most of which I was there watching in the public gallery for my job at The Sunday Times. It was relentless: An account of years and years of brutality and violence, beatings and rages and entrapment, and of the exhaustion and repetitiveness of domestic abuse, the “same things, over and over”, she told the jury.

“The world has gotten to witness the strength and bravery of my wife, freeing herself of her past,” wrote Ventura’s husband of six years, Alex Fine, 32, as she concluded her testimony. “I did not save Cassie, as some have said. To say that is an insult to the years of painful work my wife has done to save herself. Cassie saved Cassie.”

Wearing suit jackets with sharp, padded shoulders and her hair slicked-back, Ventura’s nerves dropped away as soon as she started talking each morning. She was a compelling mixture of things all at once: Articulate and sharp, but wide open to questioning; filled with horror about what she went through, but resigned to the fact she did; fatigued by the stories, but absolute in her accounts of them. “Yep that’s me,” she said when she was shown a photo of herself during a sex party, “just standing there.” Other times the defense asked her to read out explicit text messages she sent Combs. She did so unflinchingly, giving them no opponent for confrontation. It was disarming.

‘I can’t carry this anymore.’

“I can’t carry this any more,” she told the jurors when asked about why she was testifying in criminal court, having already received a $20 million settlement after she sued Combs in 2023. “I can’t carry the shame, the guilt. The way I was guided to treat people like they were disposable. What’s right is right and what’s wrong is wrong. And I’m here to do the right thing.”

As an artist on Combs’ label, Bad Boy Records, as well as his girlfriend, Ventura claimed she felt like it was her “job” to participate in “freak offs”, days-long sex parties fuelled by drugs (MDMA, ecstasy, ketamine and GHB). She argued she never wanted to do them. Combs’ legal team argued she was a willing participant.

How frequently did he use the videos of her at freak offs for blackmail, asked the prosecution. “Once is too much but several times,” she said. How frequently was he physical in the first year? “Frequently enough.” How many times was he violent with her? “Who knows.” When police questioned her about her injuries, she did not tell them Combs’ name. When friends and family told her she should leave, she was too frightened. She became “heavily dependent” on opiates.

My notebook soon became full of pages and pages of alleged atrocities. There were photos of her eyebrow split open and swollen to the size of a tennis ball when she said Combs slammed her into a bed frame; an account of her hiding under the seat of a Cadillac Escalade as he stomped on her face; a photo of her at a music festival, hair styled over her beaten eye. “I always had arnica gel for bruising with me,” she said.

But it was Ventura’s account of an alleged rape in 2018 that was the most affecting. “It was like somebody taking something from you,” she said, struggling to speak through tears, her voice heavy with hurt, barely able to say the word “rape” itself. It was a shattering conclusion.

Combs, wearing light-coloured jumpers among a sea of black suits, sat still and listening, until his legal team started the cross-examination, when he became restless, passing notes to his lawyer and drumming his fingers on the chair-arm. During a recess, he stood with his fists wide on the table. This was the physically dominating, controlling man so many of his employees, acquaintances and contemporaries had told me about when I was writing a profile on Combs for the Sunday Times Magazine.

Alongside the reporters, most of the courtroom was filled with true crime obsessives, YouTubers, Combs fans air-punching at big moments, and conspiracy theorists making wild claims about the CIA and Jeffrey Epstein.

Also there was a primped and preened Combs family, his mother’s sunglasses never coming off; his twin 18-year-old daughters in matching outfits; his 18-year-old son, Chance; and his 27-year-old son Christian “King” Combs. Each day they arrived, walking arm-in-arm out of an enormous, blacked-out Sprinter van, followed by their own film crew.

In the days after watching Ventura in the witness stand, I thought of her testimony often, the darkness and pain and bravery; of the dozens of civil cases I read filed against Combs in the years after hers, in which alleged victims credit her for being the first to come forward; and of her during the quiet, still moments in the courtroom, siting there alone, her hand on the curve of her unborn child, taking long, deep breaths and looking up towards the sky.

Photo: Getty