Mojo

Presents

Bill Ryder-Jones

From teenage guitar prodigy in The Coral, to master singer-songwriter, via shifts for Arctic Monkeys and production for Michael Head, Bill Ryder-Jones has packed a lot into his 40 years. But there’s a lot more to unpack, too, beginning with the childhood tragedy that’s defined his life and music ever since. “I’d spent years screaming into the void,” he tells Dorian Lynskey.

Photography by Marieke Macklon

Something on his mind: Bill Ryder-Jones at home in West Kirby, Wirral, 2023.

THE 2020 LOCKDOWN WAS NO PICNIC FOR ANYBODY, BUT FOR BILL RYDER-JONES it was “fucking unbearable”. His girlfriend of three months was meant to be stopping over with him in West Kirby before moving to Los Angeles but they were thrown together indefinitely. His mental health, already precarious, went downhill fast. Bad habits escalated. The relationship did not last. “We were both mad,” he says now. “The whole thing was a blur. I was taking so much Valium just to deal with the news. I’m unquestionably a different person since the pandemic.”

Ryder-Jones’s only lifeline was writing songs with titles such as This Can’t Go On and Nothing To Be Done. From that horrendous period was born Iechyd Da, the most expansive and (surprisingly) hopeful record of his career. Since leaving psychedelic urchins The Coral in 2008, his tuneful late-night confessions have taken different forms – a Wirral Bill Callahan on 2013’s A Bad Wind Blows In My Heart, skewed indie-rock frontman on 2015’s West Kirby County Primary, king of pain on 2018’s Yawn – but never one so abundantly beautiful. Three years in the making, the album has the grand cosmic ache of Mercury Rev’s Deserter’s Songs: big-sky music for introverts.

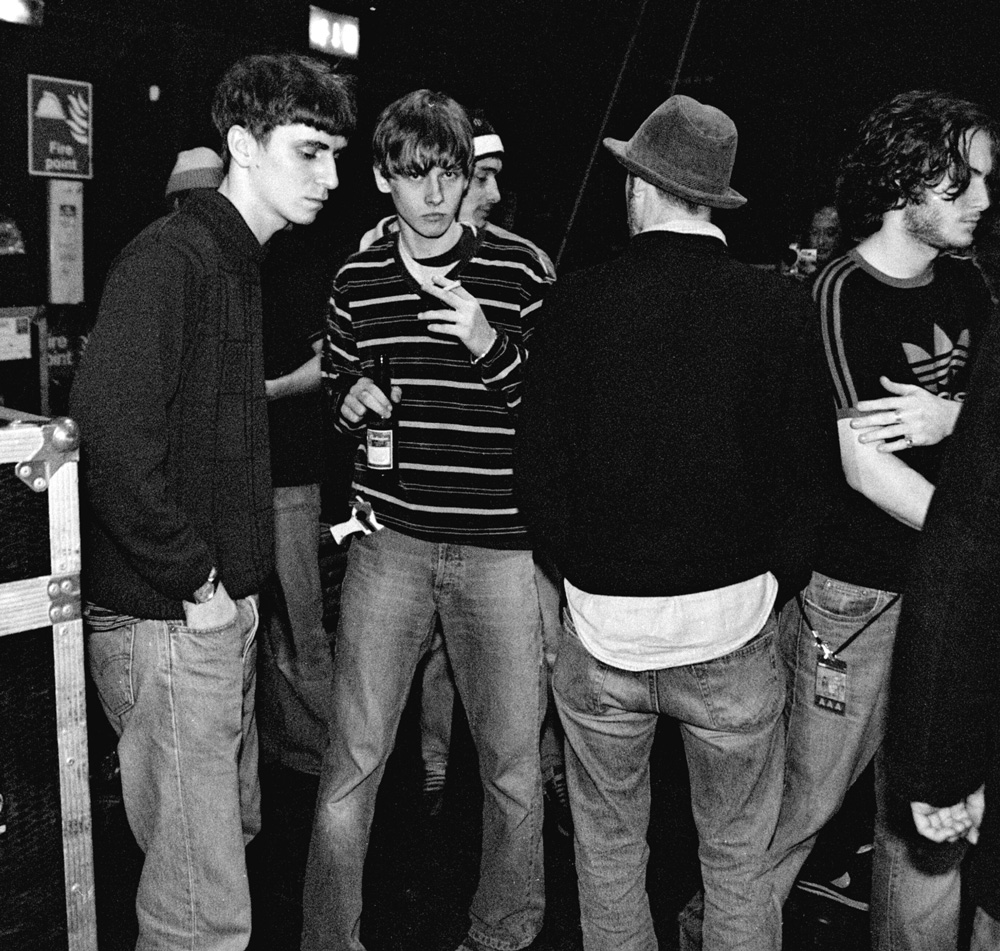

William, it was really something: The Coral take the Hoylake air, 2002 (from left) Ian Skelly, Paul Duffy, Lee Southall, James Skelly, Nick Power, Bill Ryder-Jones.

“Making the record becomes your life,” he says. “It’s a million miles away from when a group is three albums in and says, ‘We’ve got to get a synth.’ It was like, How the fuck am I going to get through this next two weeks? To write about myself and make it sound pretty just consumed me. Because I had so much time I just kept going. Like Forrest Gump.” He gives a rich, rueful laugh. “Keep running.”

“The early Coral years were mad, fun, Lawless. I was very fucking young and I was mad as fuck.”

Bill Ryder-Jones

To meet Ryder-Jones on home turf, you would never guess that he finds life a struggle. Still boyish and tousled, the 40-year-old is quick-witted, charming, an instant hit. His new girlfriend, up from London for the day, is clearly smitten when we later adjourn to the pub where he plays quizmaster every Monday night. In The Coral, his musical home between the ages of 13 and 25, Ryder-Jones’s ability to conceal his problems was itself a problem. Because he was mute in interviews and not yet a lyricist, nobody outside the band knew what he thought. Inside the band, his feelings were too easily occluded by skunk fumes. Only after he had left, in a state of psychic crisis, did he learn to stare his troubles in the eye.

“After my breakdown I thought it’s too much pressure pretending you’re fine,” he says. “I started being honest about myself and I couldn’t shut up.” He laughs at his own expense. “I’d spent years screaming into the void – someone pay attention! – but without actually saying anything, so I thought, Fuck it, I’ll do it.”

RYDER-JONES’S YAWN STUDIO IS A SHORT WALK from West Kirby station, but then everywhere is a short walk in West Kirby, a small coastal town at the tip of the Wirral peninsula. Take the train from Liverpool, it’s the end of the line. He can’t move away as long as his studio and his mother are here, but he doesn’t particularly want to. “It’s a stunning place. Quiet, calm. Nobody bothers their arse with me.”

Yawn is on the humble side, too, crammed with amps, guitars, keyboards, pedals and a piano in a state of preposterous disrepair. A picture of Goodison Park, Everton’s home ground, takes pride of place on the wall. This is where Ryder-Jones has been blossoming as a producer for the past few years: Dear Scott, by Scouse-rock elder Michael Head and his Red Elastic Band, was MOJO’s favourite album of 2022. “That’s how I live,” Ryder-Jones says with a shrug, igniting a CBD roll-up in the control room. “I don’t make money off my records.” He does love it, though, helping musicians to manifest their ideas and communicate better than his old band ever could.

From Left: On the waterfront: Ryder-Jones in 2013; backstage with The Coral, Brixton Academy, 2003.

Ryder-Jones has learned to acknowledge Daniel – an eponymous song on West Kirby County Primary, a snapshot on the cover of Yawn – but for years that felt impossible. Eating pizza with The Coral one night, their eccentric manager Alan Wills (who died in 2014) said Daniel’s name for the first time. “He threw it out like it was nothing. That name at home was hushed if it was said at all. It was a massive moment in my life – a huge amount of relief.”

On the studio wall, opposite Goodison Park, hangs a framed photograph of the nascent Coral, lined up against a brick wall. They look startlingly young, and Ryder-Jones was the youngest of the lot: just 16 when they signed to Wills’ label Deltasonic and 18 when they released their debut album. “I was just a pothead who played guitar,” he says. “The early Coral years were mad, fun, lawless.” He was a riveting guitarist, attracting praise from Noel Gallagher and Paul Weller. “I don’t even think I was the best guitarist in The Coral,” he demurs, “but I was very fucking young and I was mad as fuck.”

Among other things, Ryder-Jones had undiagnosed ADHD, complex PTSD and stage fright that caused him to vomit before shows: “That’s why I was so thin.” Looking back, he sees his mental health problems as an unexploded bomb that everybody was studiously ignoring, himself included. During the recording of The Coral’s fourth album, The Invisible Invasion, in 2005, panic attacks and night terrors precipitated his first breakdown and temporary departure. “I think the term was ‘go and get your head sorted.’ That was how it was back then.” Lured back too soon, for 2007’s Roots & Echoes, Ryder-Jones crashed again, much harder: agoraphobia, monophobia, dissociative disorder, total retreat from the world.

Ryder-Jones still has unresolved issues with The Coral but allows, “We were kids. I’m not angry at them for anything that happened to me. We all had to eat a bit of shit. A spoonful now and then doesn’t do you any harm.” He still sees the members who live in West Kirby, including regular pints with drummer Ian Skelly and a monthly coffee with frontman James Skelly, who experienced his own breakdown a few years after Ryder-Jones. “James was always very good at hiding that, as we all were. I’m without question the sanest member of that band.” He chuckles. “But certain members are tougher than I am. I was built a bit more crumbly: a Wensleydale as opposed to their Red Leicester.”

For a while, Ryder-Jones thought he was done with music forever. “I didn’t like it. It wasn’t making me happy.” He opted to study the social and economic history of Liverpool at the University of Liverpool (“the most Liverpudlian course!”) but could only manage three months. Eventually he returned to music because he didn’t know how else to live. “I had no money,” he says flatly. “I left The Coral with seven grand.”

Laurence Bell from Domino Records offered him a deal on the strength of his stark MySpace demos but Ryder-Jones’s first release, If…, was a form of concealment: an instrumental suite for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic based on Italo Calvino’s cult novel If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller. Due to his dissociative disorder, not yet medicated, Ryder-Jones can barely remember making it, but the warm reception was a pleasant shock: “I’d never really thought of myself as particularly talented.” Opening up in interviews encouraged him to do likewise in song, starting with the croaky, tentative folk-rock of 2013’s A Bad Wind Blows In My Heart.

From Left: On-stage in Liverpool, 2019; Bill the producer with satisfied customer Mick Head, 2023.

If it seems extraordinary that Ryder-Jones was psychologically fit enough to play guitar on Arctic Monkeys’ 2013 stadium tour, then he’s as surprised as you are: “Honestly it kills me when I think back. I don’t know how I did it. It doesn’t feel like me.” The tour gave him a glimpse of the road not taken. “It was mad. Massive shows with people screaming all the time. And at the same time they’re just northern divvies like The Coral. I really enjoyed it. But I wouldn’t want to do it for a living. It’s not real life, that.”

Ryder-Jones’s love of ill-starred Americana has long been evident, but his new prowess in the producer’s chair enabled him to tap into two of his foundational influences, The Beatles and the Wu-Tang Clan. “There’s so much information in those records,” he gushes. “I wanted to make a record that had a lot going on.” In the case of the soaring, yearning Iechyd Da, “a lot” includes a children’s choir, a ghostly Gal Costa sample, disco strings, Easter-egg callbacks to his older songs and Mick Head reciting a passage from Ulysses.

It’s the first album that Ryder-Jones can listen to with unalloyed pleasure. With Yawn’s post-grunge requiem, he says, “The hope had completely fallen out of it.” This time, the most daring thing he could try was optimism, of a kind. “There’s something great about life,” he croons with dazed wonder on It’s Today Again. “But there’s something not quite right.” The house on the front cover and the collage of family photographs on the back are invitations to “a brighter world,” he says. “The idea is you open up and go in.”

“You open up and go in”: Ryder-Jones amid the splendour of Yawn Studio, West Kirby, 2023.

RYDER-JONES TURNED 40 last August and he wasn’t at all happy about it. The milestone brought home all the things he would love to do – learn to drive, have kids – but doesn’t feel able to. “You think, Oh, have I missed something quite cool here? I don’t think about it a lot but when I do I think, Fucking hell… But at least I only look like I’m 37. Sadly my testicles are a bit like Dorian Gray – they’re picking up the weight.”

“Without drink or drugs I have not been calm or carefree for any period of time.”

Bill Ryder-Jones

He has a great therapist these days, he forces himself to exercise, and he’s delighted that mental health is no longer taboo, but nothing is easy. “It never goes away,” he says with an exhausted sigh. “I’ve just been managing. That’s how I live – just managing from one day to the next. Without drink or drugs I have not been calm or carefree for any period of time. I pretty much don’t leave West Kirby – certainly not on my own. It’s fucking shit but what are you going to do?”

Does he think it all comes back to that day in Wales in 1991?

“My family definitely has a genetic predisposition to mental ill health but my problems are very specific,” he says carefully. “It’s sort of textbook the way I’ve reacted to an event like that.” He clears his throat. “I can’t picture myself without Daniel’s death. Everything I have… When he died I started wearing his clothes. I started to play the violin and piano because he did – filling a hole for my mother. That took me on that journey and now I’m here and I’ve got a studio and it’s great.”

Ryder-Jones looks around the control room and falls silent, unsure what to do with the insoluble fact that the worst thing that ever happened to him is the reason why he is here.

Ryder’s on the storm

Four key Bill Ryder-Jones albums on the path to Iechyd Da.

The Coral

The Invisible Invasion

(Deltasonic, 2005)

Songwriting credits alone are a poor indicator of Ryder-Jones’s importance to The Coral, but he peaked with three on their Portishead-produced last album before his forced sabbatical, including the ghostly A Warning To The Curious and the unbridled guitar mayhem of Come Home. A band growing up yet falling apart.

Songwriting credits alone are a poor indicator of Ryder-Jones’s importance to The Coral, but he peaked with three on their Portishead-produced last album before his forced sabbatical, including the ghostly A Warning To The Curious and the unbridled guitar mayhem of Come Home. A band growing up yet falling apart.

Bill Ryder-Jones

A Bad Wind Blows In My Heart

(Domino, 2013)

After the wholly instrumental If…, Ryder-Jones emerged as a singer-songwriter like someone waking from a long slumber and getting used to his own voice. “Sometimes I feel I don’t exist,” he rasps on Christina That’s The Saddest Thing. Like Bill Callahan or Elliott Smith, he excavates his troubles via delicate folk rock.

After the wholly instrumental If…, Ryder-Jones emerged as a singer-songwriter like someone waking from a long slumber and getting used to his own voice. “Sometimes I feel I don’t exist,” he rasps on Christina That’s The Saddest Thing. Like Bill Callahan or Elliott Smith, he excavates his troubles via delicate folk rock.

Bill Ryder-Jones

West Kirby County Primary

(Domino, 2015)

A fter junking a whole album with producer James Ford, Ryder-Jones turned up the amps on the post-Coral release that sounds most like a full-blown rock band, with thick shades of Pavement and Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, his “favourite group of all time”. Satellites and Daniel are the two soul-baring cornerstones.

fter junking a whole album with producer James Ford, Ryder-Jones turned up the amps on the post-Coral release that sounds most like a full-blown rock band, with thick shades of Pavement and Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, his “favourite group of all time”. Satellites and Daniel are the two soul-baring cornerstones.

Bill Ryder-Jones

Yawn

(Domino, 2018)

“ It was me doubling down on being fucking sad,” Ryder-Jones says of his noisiest, most desperate album. Heavily influenced by Red House Painters, this beautifully produced slowcore lament moves like a black freighter: majestic but oppressive. The following year, he rearranged the whole thing for piano as Yawny Yawn.

It was me doubling down on being fucking sad,” Ryder-Jones says of his noisiest, most desperate album. Heavily influenced by Red House Painters, this beautifully produced slowcore lament moves like a black freighter: majestic but oppressive. The following year, he rearranged the whole thing for piano as Yawny Yawn.

Marieke Macklon(2); Howard Barlow/Getty; Ian Whent, Chris Lever/Shutterstock, Matt Thomas, John Johnson