Mojo

Presents

Lankum

In 2023, LANKUM crashed through the boundaries of ‘folk’ to win thousands of new fans. Also in the van: fellow Irish pathfinders LISA O’NEILL and JOHN FRANCIS FLYNN. As they tell JIM WIRTH, the unexpected attention comes with benefits: “The librarian was like: ‘I know who you are.’”

Photography by ELLIUS GRACE

Folk explosion: Lankum (from left) Radie Peat, Ian Lynch, Daragh Lynch and Cormac MacDiarmada take their “droney depressing music” to the masses.

THERE MAY NOT BE A FORTUNE to be made in the vanguard of a wave of Irish artists spinning off traditional music into wilder terrain, but Lankum are finding that the success of their fourth LP, False Lankum, comes with significant side-benefits.

“I just got to skip the queue to get my library card,” says singer Radie Peat as she and bandmates Daragh Lynch and Cormac MacDiarmada meet MOJO in a pub on Dublin’s northside, not far from the converted factory building where the band rehearse.

“The librarian was like: ‘I know who you are, so you don’t need proof of address or ID.’”

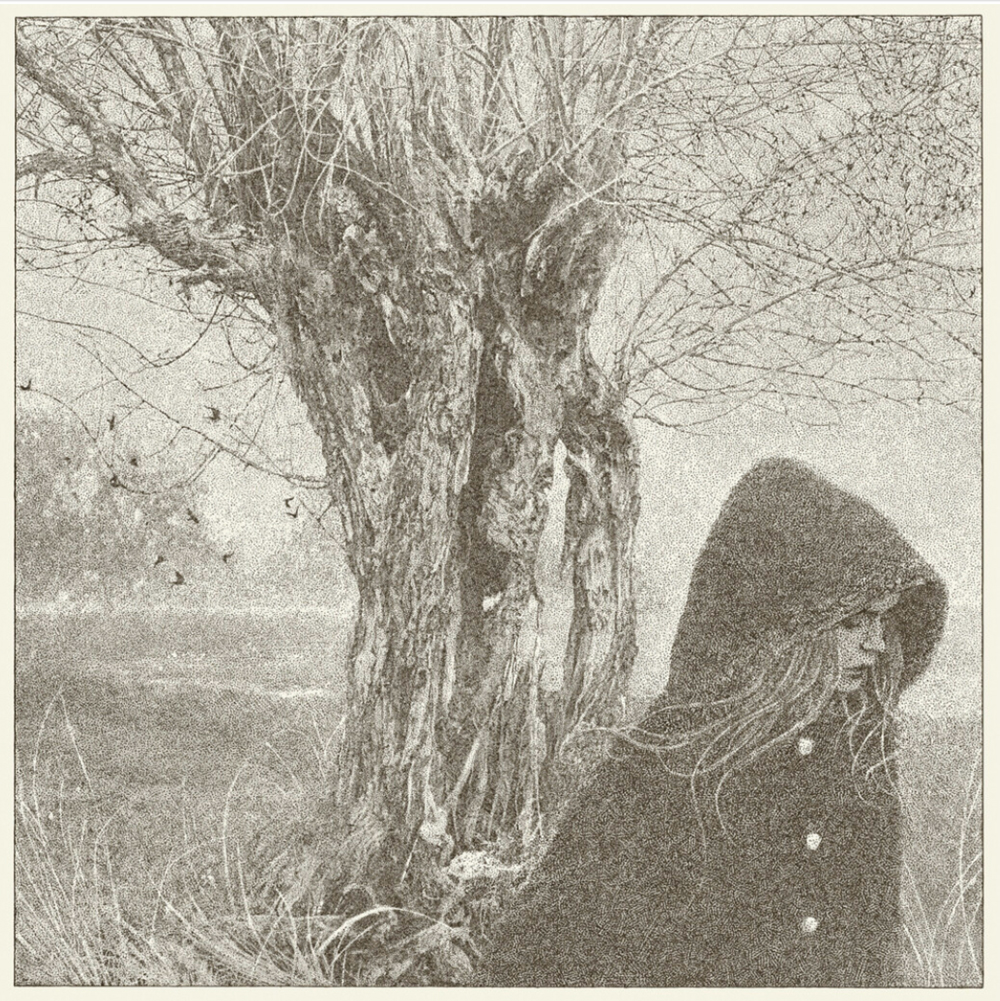

Taking a chance: Lisa O’Neill makes powerful, strange and intimate music.

“I was in the post office the other day setting up the PO Box for the fucking band,” adds the refreshingly sweary Lynch. “And your man who was behind the counter was like: ‘Oh, yeah, here. I’ll sort that out. Look, go to the top of the next queue. Just ask for me.’”

“If that’s all that ever happens from us making music, just bureaucracy getting easier…” says Peat.

“Happy days,” says McDiarmada.

Airy sweet and bible black, False Lankum’s melding of seafaring songs, gloomy originals, tender ballads and thunderous noise has taken the band of thirty-and-fortysomething multi-instrumentalists to unexpected places.

When they were playing for beer at pub sessions a decade ago, signing on and singing together for fun, it would have been a push for them to imagine that 2023 would find them selling out three nights at Dublin’s 1,500-capacity Vicar Street, where past headliners include Ministry, Bob Dylan and Jedward.

Being nominated for this year’s Mercury Prize – and playing at the awards ceremony – was an extreme culture shock for a band who were once darlings of the European squat punk scene.

“We felt so out of place,” says MacDiarmada.

Lynch, meanwhile, remembers seeing the corporate rock names on the seating plan and thinking: “This is a list of who’s going to hell.”

From Left: The year of living famously: The uncategorisable Lankum; The band at September’s Mercury Prize show

LANKUM HAVE BEEN honing their diabolical, folk-toned acoustic racket since Lynch and his older brother Ian started out playing antisocial riffs on traditional songs at Dublin punk gigs. They linked up with childhood friends Peat and MacDiarmada – both of whom have a background in Irish traditional music – in time to record 2014’s Cold Old Fire (released under the later-regretted band name Lynched), appearing on Jools Holland’s Later… in 2015 as an unsigned act.

Rough Trade picked them up for their first album as Lankum, 2017’s Between The Earth And Sky, their deep-bass drones and black metal dynamics gathering storm force on 2019’s gloomy The Livelong Day.

“IT’S TOO COMPLICATED TO DESCRIBE WHAT IT IS WE’RE TRYING TO DO. THE MUSIC IS THE EXPLANATION.”

Lankum’s Radie Peat

False Lankum, though, is a significant escalation, producer John ‘Spud’ Murphy helping to broaden their sound to an ominous acoustic swell – the Incredible String Band of the damned – as they pieced the album together during the Covid lockdown in a Napoleonic War-era Martello Tower overlooking Dublin Bay.

“We were living in extreme circumstances, but also in very intense natural beauty,” says Peat. “We got to see the sea every day.”

“The weather was amazing,” says MacDiarmada.

“Then the room where we made the music in has no windows, so you’d go in there and you’d lose a sense of time,” says Peat.

“Like fucking sensory deprivation,” says Lynch.

False Lankum revels in contrasts; pure horror on their exhumation of the traditional Go Dig My Grave, wistful bewilderment on MacDiarmada’s version of Newcastle, and a more Floyd-ish big-picture ennui on Daragh Lynch’s gigantic closer, The Turn. Surprisingly, the most aggressively idiosyncratic record they have made has ended up being a commercial breakthrough.

Whether this represents a sudden upturn in the fortunes of traditional music is a moot point. Lankum have an immense knowledge of folk esoterica, and an affinity for the electrified tradition exemplified by Planxty and Sweeney’s Men, while their force-10 harmonies nod to The Watersons and Swan Arcade. However, there is as much Rudimentary Peni or Sunn O))) in Lankum’s DNA, and the band have largely given up trying to describe what they do.

“If you’re getting a taxi sometimes and the driver is like: ‘Oh, you’re in a band…,’” says Peat, wincing.

“‘What kind of music do you play?’” smiles Lynch.

“Sometimes I just lie because I just don’t really know what to say,” says Peat. “And I don’t think they really would like to hear the truth. So I’m like: just indie.”

“It’s droney depressing folk music,” jokes MacDiarmada.

“It’s too complicated to list our influences or try to come up with words that describe what it is that we’re trying to do,” says Peat. “The music is the explanation; the album plus the artwork – that’s what we have to say, that’s what we’re getting at. The only thing that explains it is the actual thing.”

From Left: On-stage at Vicar Street, Dublin, May 29, 2023; 2017’s Between The Earth And Sky and this year’s False Lankum.

LANKUM’S TASTE FOR THE UNCATEGORISABLE IS shared by some close Dublin contemporaries. Signed to Rough Trade on Lankum’s recommendation, Lisa O’Neill has been much fêted this year for her uncanny fifth LP, All Of This Is Chance. An elemental melding of intense lyricism, autumn-toned instrumentation and O’Neill’s storm-lashed voice, key songs like If I Was A Painter, Whisht, The Wild Workings Of The Mind and the transcendent Old Note feel like a horse-drawn approximation of early Patti Smith. This powerful, strange, intimate music drew her an audience of 1,800 for a March show at London’s Barbican.

“It is more than validation,” she tells MOJO, nursing a broken shoulder as we meet her at the James Joyce Centre, a short walk from central Dublin. “You’re met with an understanding and it gives you a strength in your own visions.”

From Ballyhaise in County Cavan, O’Neill moved to the capital as a teenager to study songwriting at Ballyfermot College and had self-released her first two LPs – 2009’s Lisa O’Neill Has An Album and 2013’s Same Cloth Or Not – before she first ran into the Lynch brothers.

“I remember meeting them at a session up on South Great George’s Street, and then I met Radie maybe 10 years ago,” she remembers, adding forcefully: “I moved here 24 years ago, and I met these people in the folk scene in the last 10 to 15 years. I had a life before that.”

O’Neill found her uncompromising voice while playing Sunday night sessions at the International Bar, on the south side of the River Liffey (“If you were barred from every other pub in Dublin, you might be allowed in there,” she recalls). She and Lankum have shared interests (O’Neill mixed trad-arrs and originals on 2018’s Heard A Long Gone Song), but they are – to paraphrase one of O’Neill’s songs – birdies from another realm, as indeed is John Francis Flynn, whose second LP, Look Over The Wall, See The Sky, offers another cubist take on traditional music.

Avant noise and eerie Tricky paranoia mingle with virtuoso tin whistle, as Flynn rewires old songs – The Zoological Gardens, Ewan MacColl’s Dirty Old Town – into a very modern portrait of his home city.

Signed after supporting Lankum on tour, Flynn played sessions alongside O’Neill for years, and is excited by the creative space that his circle have opened up. “It’s really heartening for people who really want to experiment,” he tells MOJO. “The stuff that Lankum have put out recently, that is really incredibly challenging music.

“We were all playing together in the city for so long and it’s a very beautiful thing that everyone’s doing so well,” he adds. “It’s a bit intimidating coming up after them.”

From Left: Dig the new breed: Lisa O’Neill performing in Barcelona, February 8, 2017; John Francis Flynn on-stage at Curraghmore House, Waterford, Ireland, July 31, 2022.

HOWEVER, LANKUM’S YEAR has not been an entirely enviable one. For all the set-piece successes – not least: headlining Birmingham’s experimental Supersonic festival – autumn live dates in Denmark and America were cancelled, an official statement explaining that it was necessary “to preserve the health and wellbeing of our band members”.

Peat’s daughter is under two, and juggling Lankum and parenthood has not been easy. “I bring my child on tour with us and it’s difficult,” she says. “A lot more difficult than you would imagine.”

When MOJO show up, Lankum are enjoying a bit of down time. Ian Lynch – whose year has also encompassed side-project One Leg, One Eye and a successful extreme folk podcast, Fire Draw Near – is in America (“on an old-school DIY punk tour” according to his Twitter feed). However, Lankum have shows booked for the winter, while Peat is simultaneously promoting CYRM, the glowering debut album from her other band, ØXN.

Plans for the longer term, though, are being kept vague. “Any time we’re asked this question, the one thing we all say is that we want to do a soundtrack,” says Daragh.

In the meantime, Lankum have blessings to count.

“I’m glad we started doing what we’re doing a little bit later in life,” says Peat.

“There’s less risk of believing your own hype,” adds Daragh. “Like swanning around wearing fucking fancy jackets and looking around to see if people know who you are.”

“I occasionally try and take a step back,” says MacDiarmada. “Because it’s amazing to be acknowledged, it really is.”

As they finish up their pints and teas and head out onto Prospect Road, Daragh discovers that his bike – chained to a railing outside – has been severely mangled. Reckless Phibsborough bus drivers are blamed, but whatever the damage, Lankum have plenty to feel positive about. Peat goes into a little reverie as she remembers hearing Iggy Pop playing their blood and thunder assault The New York Trader on his BBC Radio 6 Music show.

“And he said, in his Iggy Pop voice, the word ‘Lankum’. And I was: THAT IS SO COOL!” she twinkles.

All this and priority treatment at the library. As Peat says with a shrug: “Sometimes you have to just deliberately let your inner child be happy.”

BALLADS & BEYOND

Five more voices taking folk into the future.

THE MARY WALLOPERS

A sort of reckless neo-Pogues with a slight King Kurt undertone, Dundalk’s Mary Wallopers are a riot of colour (mostly green) live, but the group founded around brothers Andrew and Charles Hendy have hidden depths. There’s beer and there’s banjos, but 2023 second LP Irish Rock N Roll reveals the upstart political conscience beneath the mayhem.

NAIMA BOCK

Once a member of south London punks Goat Girl, Bock ran away to join the folkie fairies, singing trad with the Broadside Hacks collective before releasing her luminous Sub Pop debut Giant Palm in 2022: samba-toned dream pop with distant echoes of Fairport Convention. Expect a more stripped-down approach for her next project.

Once a member of south London punks Goat Girl, Bock ran away to join the folkie fairies, singing trad with the Broadside Hacks collective before releasing her luminous Sub Pop debut Giant Palm in 2022: samba-toned dream pop with distant echoes of Fairport Convention. Expect a more stripped-down approach for her next project.

JIM GHEDI

The Sheffield experimentalist graduated into free-form guitar with 2015’s Home Is Where I Exist, Now To Live And Die. Two albums of John Fahey-style instrumentals with Toby Hay come highly recommended, but his unfettered Son David from 2021’s In The Furrows Of Common Place better encapsulates his mix of bookish Bert Jansch and hunky James Dean.

The Sheffield experimentalist graduated into free-form guitar with 2015’s Home Is Where I Exist, Now To Live And Die. Two albums of John Fahey-style instrumentals with Toby Hay come highly recommended, but his unfettered Son David from 2021’s In The Furrows Of Common Place better encapsulates his mix of bookish Bert Jansch and hunky James Dean.

SHOVEL DANCE COLLECTIVE

From the same stable as nu-post-rockers Caroline (with whom they share members), the nine-piece Shovel Dance Collective mixed drones, trad material and found sounds on their 2022 debut The Water Is The Shovel Of The Shore. Art school kids with a taste for the gothic, they may be Lankum’s closest musical relatives outside of Dublin.

From the same stable as nu-post-rockers Caroline (with whom they share members), the nine-piece Shovel Dance Collective mixed drones, trad material and found sounds on their 2022 debut The Water Is The Shovel Of The Shore. Art school kids with a taste for the gothic, they may be Lankum’s closest musical relatives outside of Dublin.

ANGELINE MORRISON

Born to a Jamaican mother and a father from the Outer Hebrides, Morrison’s 2022 outing The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs Of Black British Experience was an era-defining collection of brilliantly-tooled trad homages, telling true stories of the nation’s centuries-old black community. When she last spoke to MOJO, she was working on an album about alchemy.

Born to a Jamaican mother and a father from the Outer Hebrides, Morrison’s 2022 outing The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs Of Black British Experience was an era-defining collection of brilliantly-tooled trad homages, telling true stories of the nation’s centuries-old black community. When she last spoke to MOJO, she was working on an album about alchemy.

Ellius Grace; Sorcha Frances Ryder, Getty (4)