Mojo

Presents

Sons Of Kemet

For a decade, Shabaka Hutchings’ SONS OF KEMET have blazed a trail for British jazz, bringing carnival energy, Afrocentric attitude and, sometimes, more than one tuba. And as they assure DANNY ECCLESTON, they’re not done evolving. “The area that Caribbean music can occupy is infinite!”

Photography by TOM OLDHAM

Looking for apparitions: Sons Of Kemet (from left) Shabaka Hutchings, Tom Skinner, Theon Cross, Edward Wakili-Hick at the Total Refreshment Centre, Stoke Newington, London, March 23, 2021.

VISITORS TO NORTH LONDON’S LIVINGSTON STUDIOS IN THE AUTUMN OF 2019 could easily have stumbled across something quite odd: four grown jazz musicians lying on the floor of the live room, in the pitch dark, screaming and screaming. Jazz can be a lot of things, the open-minded observer might have mused, but… this?

“It was cathartic!” laughs Shabaka Hutchings, the saxophonist-leader of Sons Of Kemet and the director of this unusual scenario. “Before every track I got everyone to do these breathing exercises. Thirty really deep breaths and you keep the last one in. I really felt it put us in a space that was together.”

For the final track on Sons Of Kemet’s latest album, however, he had something more extreme in mind. As the intense cacophony played back in their headphones, the four men on the floor wailed, shrieked and ululated until they were spent.

“There’s complete darkness,” remembers Hutchings, “and we’re really letting it out. You have cans on, and you can’t hear anyone, not even your own voice, so you’re uninhibited. You’re giving out pure emotion.”

SOK skank down in Babylon: (from left) Hutchings, Wakili-Hick, Cross, Skinner.

“UNINHIBITED” IS A GOOD WORD FOR SONS OF KEMET. FREQUENTERS OF THEIR decade of live shows will have seen a development that’s felt less about honing and more like re-wilding. The original quartet – the imposing Hutchings on tenor mainly, but sometimes clarinet; drummers Tom Skinner and Seb Rochford; Oren Marshall on tuba and ‘Orenophone’ (a kind of unwieldy, unwound Sousaphone) – were extraordinary enough: a meld of jazz, Caribbean and near eastern musics that rattled the cutlery of diners at London’s sedate jazz clubs. Their evolution – first Marshall handed over to his tuba protégé Theon Cross; then Rochford left and Edward Wakili-Hick stepped in – has coincided with an upsurge in the physicality, generic promiscuity and (yes, let’s say it) popularity of British jazz music.

Uninhibited certainly describes Hutchings’ saxophone playing on Black To The Future – their fourth album since 2013 – specifically the final section of May The Circle Be Unbroken, where his blowing fractures into an angry storm of desperate cries and shouts. Quizzed on it by MOJO, Hutchings almost sounds like he’s blushing.

“Er, yeah – that was a bit intense,” he whispers. “I mean, you encounter those moments, where it feels like you’re an outlet for a different spirit. Or a different personality. And when it happens, it’s not worth going back to it and trying to think it through. You’ve almost got to pretend it didn’t happen. Then the magic might come back again.”

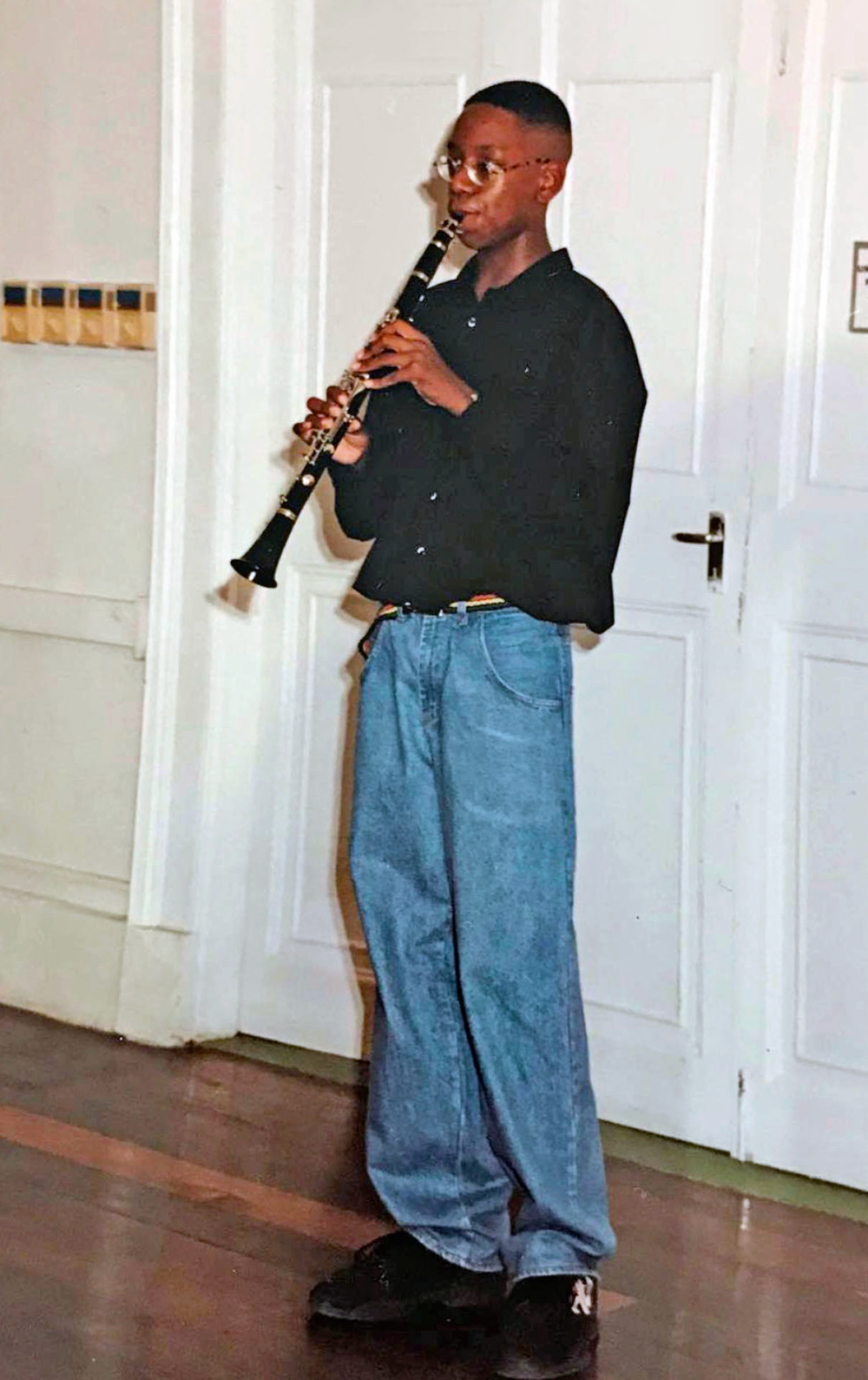

While Hutchings is keen to avoid the pitfalls of over-thinking, he remains one of the great ponderers of contemporary British music (don’t get him started on ‘Quantum Afrofuturism’). Born in London in 1984, Shabaka Akua Lumumba Kamau Hutchings was raised in Birmingham and Barbados by a single mother. Returning to the UK in his teens, he studied classical clarinet at the Guildhall School Of Music, while his sax education progressed in groups as diverse as Seb Rochford’s Polar Bear, Mulatu Astatke and the Sun Ra Arkestra. His current status among peers in British improvisational music is unquestioned – front and centre in Sons Of Kemet, spacetronic trio The Comet Is Coming and with South African spiritual jazz tyros in Shabaka & The Ancestors, to name only his three highest-profile projects. “He is a leader,” says Tom Skinner. “Listen to all the young tenor players – you can hear Shabaka in all of them. He has kicked in a door for this generation.”

“What Shabaka’s shown is don’t be afraid to look to yourself and your own roots. It doesn’t have to be American jazz.”

Tom Skinner

Yet in the mists of 2011, Hutchings’ decision to begin his band-leading life in a two-drummers, sax and tuba combo seemed eccentric – quadruply so at the March 2013 show at Camden’s Forge venue that peaked with four tubas on stage. What, literally, was he thinking?

“I recently found my old notebook from the year I formed Sons Of Kemet so I could actually look through the process,” he says. “I was thinking of all kind of combinations. At one point I had [drummer] Mark Sanders, and I was thinking a guitarist, maybe David Okumu…”

Eventually, Hutchings settled on Marshall but was torn between Skinner and Rochford, until he thought, “Why not both? I was listening to this Tony Malaby album, Apparitions,” he recalls. “He had two drummers on that and I loved the way they interacted, not with one taking the groove but each communicating with the other.”

The Kemet sound, with two drummers shifting focus and the tuba swaggering about, has always felt mobile and purposeful. It turns out it’s a legacy of Hutchings’ earliest musical experiences: playing bass drum in a marching band.

“Tuk is the traditional music of Barbados,” Hutchings explains. “You’ve got a bass drum, a snare drum, a triangle and a guy on a flute. Unlike the larger islands in the Caribbean – which were big enough to have hidden places where African religious rites could be observed – on Barbados, that cultural retention went under the radar. It slipped into their military marching music, into the syncopation of tuk.”

From Left: Sons Of Kemet get tuk in on-stage at the 2019 Latitude Festival, Suffolk; Hutchings with Kamasi Washington, Ghent Jazz Festival, July 2017

HUTCHINGS TALKS A LOT ABOUT SONS OF KEMET as a vessel for the myriad musics of the African diaspora, and his example is infectious. Dreadlocked Wakili-Hick has adjusted his approach (and his name) to embrace more of his West African heritage. “I’ve been introducing kpanlogo,” says the drummer in drowsy Yorkshire tones, “a Ghanaian drum. And an igba – a Nigerian talking drum. Bringing different sounds in.” Cross is the group’s bass music specialist, versed in grime (he’s lent his tuba to Kano, Little Simz and Ruff Sqwad) but also steeped in ‘blocos’, the Brazilian-style carnival bands he played in from ages 12 to 17. “I suppose I bring that carnival energy to Sons Of Kemet, where the audience is part of the band,” he reflects. “It’s like an acoustic sound system.”

What it isn’t is conformity to ‘classic’ jazz templates, insists Tom Skinner. “What Shabaka’s shown is don’t be afraid to look to yourself and your own roots and experience and use that as the basis for a sound,” says the drummer. “It doesn’t have to be American jazz.”

Bringing his roots and experience to the stage and the studio has, for Hutchings, meant foregrounding the history of African people. On SOK’s 2018 album, Your Queen Is A Reptile, the tracks were named for an alternative pantheon of ‘queens’: pioneering black women including Angela Davis and Harriet Tubman. And although its core grooves were laid down in advance of George Floyd’s killing on March 25, 2020, Black To The Future opens with a poem written by Joshua Idehen in its immediate aftermath. Railing at the structures that would constrain or define black people, it aims a barb at the UK’s former equality tsar, Trevor Phillips. “I hope I never bump into him actually!” laughs Hutchings, before delicately addressing the problematic position of “anyone who’s used in ways that can be considered tokenistic”.

The saxophonist is more bluntly critical of responses to Black Lives Matter that he describes as “taking up space”. “If your response to this traumatic event is, you know, thinking about it for half an afternoon and then spewing out what you think about it on social media,” he says, “this isn’t necessarily the kind of soul searching that’s going to remedy the problem.”

The new album’s last track, Black, is also voiced by Joshua Idehen. Its last words, “Leave us alone”, are uncompromising. What do they mean to Hutchings?

“I take it to mean ‘leave black culture alone’, or leave African cultural knowledge to develop on its own terms, without the gaze or interpretation of external forces,” he says. “Leave black people to develop without the fear of being harassed or being depicted. It’s about our freedom to be multiple.”

From Left: Young Shabaka’s first professional gig in 1995, aged 11; early SOK line-up (from left) Skinner, Oren Marshall, Seb Rochford, Hutchings, 2013.

DEFINITION BY EXTERNAL forces was barely an issue for British jazz musicians before their recent exposure to the spotlight, but Hutchings and co are already working on confounding expectations. In November 2020 the BBC revived its venerable Jazz 625 strand for a TV special on UK jazz acts including Nubya Garcia, Moses Boyd and Ezra Collective. Rather than strapping on the tenor and blowing viewers’ heads off, Hutchings applied his clarinet to a mournful revision of Black To The Future’s In Remembrance Of Those Fallen.

“It wasn’t a statement, as such,” says Hutchings. “But you know, we’re never going to satisfy anyone’s idea of what we’re supposed to be. We are whatever we are at that particular moment. The pandemic, for me, felt like a moment for reflection. And as I get older I realise that everything doesn’t have to be shouting in your face.” He laughs. “Sometimes you can just tell someone your opinion.”

A scream to a whisper? Hutchings says he can visualise the next stage of Sons Of Kemet’s evolution – exploring lower volumes, more dynamics, but rawer sax sounds. Meanwhile, he has been listening to lots of soca and calypso, a way of battling what he calls American music’s “hegemonic allure”.

“The area that Caribbean music can occupy is infinite,” he says. “It’s exciting because it means that no one can predict what the future of music is gonna be. People will always say, ‘Oh the music scene is dying…’ For me that’s the worst type of outlook, and it makes no sense…”

He pauses. A little steel enters the lilt of his voice. “It’s like, are you even listening?”

RISING SONS

The fruits of Kemet, so far, by Danny Eccleston.

BURN

(Naim, 2013)

Sons Of Kemet’s first phase, with Seb Rochford on half the drums and Oren Marshall on tuba and Orenophone, showcased what Hutchings calls “a more exploratory, jazz-based group”. Yet the tenorist’s urgency and Marshall’s reggaefied low-end blurts marked them out from the very start. A criticism? Too much reverb.

Sons Of Kemet’s first phase, with Seb Rochford on half the drums and Oren Marshall on tuba and Orenophone, showcased what Hutchings calls “a more exploratory, jazz-based group”. Yet the tenorist’s urgency and Marshall’s reggaefied low-end blurts marked them out from the very start. A criticism? Too much reverb.

LEST WE FORGET WHAT WE CAME HERE TO DO

(Naim, 2015)

Theon Cross’s arrival made SOK “more full-frontal, more of a band,” says Hutchings. Crashing into the opening In Memory Of Samir Awad about two-thirds in, the tubist certainly seems to pull everything together. Meanwhile, the nine-minute Afrofuturism is the closest they’ve come, says Hutchings, to Barbadian ‘tuk’.

Theon Cross’s arrival made SOK “more full-frontal, more of a band,” says Hutchings. Crashing into the opening In Memory Of Samir Awad about two-thirds in, the tubist certainly seems to pull everything together. Meanwhile, the nine-minute Afrofuturism is the closest they’ve come, says Hutchings, to Barbadian ‘tuk’.

YOUR QUEEN IS A REPTILE

(Impulse!, 2018)

Everything feels more pointed on SOK’s third, where Anglo-Nigerian poet Joshua Idehen brings the politics and Tom Skinner, paired with a transitional cast of drum partners, earns his corn. My Queen Is Harriet Tubman made the soundtrack of Beyoncé’s 2019 Homecoming doc, much to the delight of Theon Cross.

Everything feels more pointed on SOK’s third, where Anglo-Nigerian poet Joshua Idehen brings the politics and Tom Skinner, paired with a transitional cast of drum partners, earns his corn. My Queen Is Harriet Tubman made the soundtrack of Beyoncé’s 2019 Homecoming doc, much to the delight of Theon Cross.

BLACK TO THE FUTURE

(Impulse!, 2021)

More budget meant more studio time to brew more intense grooves, over which Hutchings’ layered woodwinds evoke a forest of birds. Depth and richness ensue, but also SOK’s most powerful statements, with guest vocalists and Hutchings’ sax idols Steve Williamson and Kebbi Williams stoking the fire.

More budget meant more studio time to brew more intense grooves, over which Hutchings’ layered woodwinds evoke a forest of birds. Depth and richness ensue, but also SOK’s most powerful statements, with guest vocalists and Hutchings’ sax idols Steve Williamson and Kebbi Williams stoking the fire.

Tom Oldham (2), Richard Gray/EMPICS Entertainment/PA, Getty