Mojo

Presents

“I Am What I Am”

So said an unapologetic Lou Reed speaking to MOJO seven weeks before his death. Mark Paytress, who interviewed him during that final encounter, leads our definitive tribute to rock’s ultimate iconoclast as we celebrate a life lived without fear or compromise…

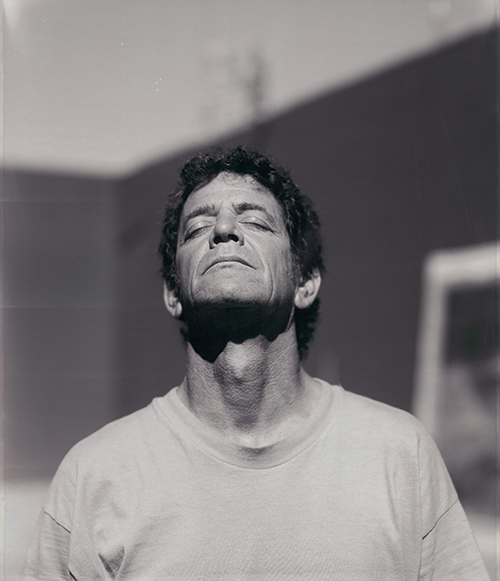

Who loves the sun: Lou Reed in 2006

IT’S 2013. LOU REED IS JET-LAGGED. He’s also in the early stages of recovery after a liver transplant in May. His elegant, rough diamond voice is now summoned up from the throat, rather than the spleen, but the famous indifference in his drawl is unmistakable. He’s a little more round-shouldered now, and when he rises and walks about at the end of the interview, his frailty is more apparent still.

A few weeks earlier, Reed had declared himself “a miracle of medicine”, insisting that he was bigger and stronger than ever. It was fighting talk from a man with a long history of sparring, whether with journalists, over whom he always had the upper hand, or with his psyche, an altogether more complicated battle.

The location is well-chosen. We are in Trident Studios in Soho where, 41 summers ago, Reed created the work upon which his career turned. That was Transformer, and Lou’s here today, on September 4, to remember those times. Looking back is not something he does through choice, but there’s a book to promote, a lavish, atlas-sized visual chronicle of Reed’s ’70s stylistic reinventions. Phantom of Rock, Rock’n’Roll Animal, Godfather of Punk – they’re all here and much else besides.

The book – also called Transformer – draws on the work of Reed’s long-time friend and photographer Mick Rock. He’s here too. It’s been a long day, so as they steel themselves for one final interview, Rock and Reed take an unscheduled break as Lou shows off his new Leica camera to a man who knows a thing or two about photography. “Isn’t it wonderful? And the weight,” Reed drools, with Warhol-like wonder. “This is not a piece of plastic…” It’s several minutes before the Rock’n’Reed Gadget Show grinds to a halt.

Lou stares at your correspondent impassively and offers an polite “Shall we?” As our conversation runs from Transformer to Hollywood via Othello, he is by turns glib, generous, protective, fatigued, funny, passionate and, when the mood takes him, trigger happy. His combative spirit seems intact during one particular moment, suggesting Lou might be in better shape than he looks. “Why would I?” he grumps, when I ask if he’ll ever write a memoir. “Set what record straight? I am what I am, it is what it is, and” – bingo! – “fuck you.”

“The Ramones make everybody else look wimpy – Patti Smith & me included, man!”

In truth, it’s not as if a Lou Reed autobiography would come with a cast-iron guarantee of total veracity. His interviews have always been a minefield of irony and false trails. Even his lyrics, as plain-speaking and personal as any in rock, are more true to the work than to the author. “Put all the songs together and it’s certainly an autobiography,” he once declared, “but not necessarily mine.”

There was a period in Lou Reed’s life when he wasn’t quite so circumspect. In 1971, several months after he’d walked out on The Velvet Underground, Reed wrote an essay for No One Waved Good-Bye, a 128-page anthology and self-styled ‘Casualty Report on Rock and Roll’. In Fallen Knights And Fallen Ladies, Reed unpicked the pressures of fame with particular reference to Brian Epstein (“a pawn of circumstance”) and “perfect” Brian Jones. It was a remarkable piece, full of insight and enough empathy to make the reader wonder whether, like Waldo Jeffers in Reed’s 1962 short story (and 1967 song) The Gift, he’d wrapped up his jilted self and mailed it to the world.

Lou, who’d announced in the spring of ’71 that he was no longer a singer but a poet, bowed out with a lesson for aspiring rock stars. “Performer beware,” he cautioned. “If you come looking for love, come prepared with a thick skin or a thick heart… Don’t depend on anyone.”

His decision, though surprising, made sense for Lou’s literary ambition, like his throbbing rock’n’roll heart, was hard-wired. Almost a decade earlier, in 1962, he’d written an untitled piece for the launch issue of a magazine he’d co-founded while at Syracuse University. Its opening sentence was no less transparent: “He’d always found the idea of copulation distasteful, especially when applied to his own origins.” Sex, disgust, the family… When John Cale later said that Lou’s best work owed its existence to his upbringing, he was probably right.

Home for the young Lewis Reed, born March 2, 1942, was a respectable, ranch-style residence in Freeport, Long Island. Brooklyn, Lou’s birthplace, was just 20 miles away but for his family, aspiring, Jewish and to some extent subjugated by a domineering father, suburbia was seventh heaven. Their son had another name for the place: ‘Nowhere’.

Reed’s salvation was the radio, spluttering out rock’n’roll, R&B and his beloved doo wop as if direct from city street corners. “Despite the amputation,” as he sang on Rock & Roll, one of his least contentiously autobiographical songs, the radio stations beamed in from New York reconnected Reed to his roots.

Any hopes that Lou might help run his father’s accountancy business, or at the very least continue with his piano studies, vanished. As he explained in the Fallen Knights essay, “At the age when identity is a problem, some people join rock’n’roll bands and perform for other people who share the same difficulties.”

His entry in the 1959 Freeport High School yearbook – “no plans, but will take life as it comes” – speaks volumes about Reed’s early attitude. But he wasn’t indolent. Several months earlier, he’d ventured up to the big city with two classmates, and cut two sides of homespun doo wop.

The big event in Lou’s early life came shortly after graduating from school in June 1959, when he was pronounced unfit for adult life until he’d undergone a course of electroconvulsive therapy – thrice weekly for eight weeks. His parents wanted to ‘cure’ his suspected homosexuality, he explained years later, though depression, and even his disobedient attitude have also been cited as reasons for his treatment.

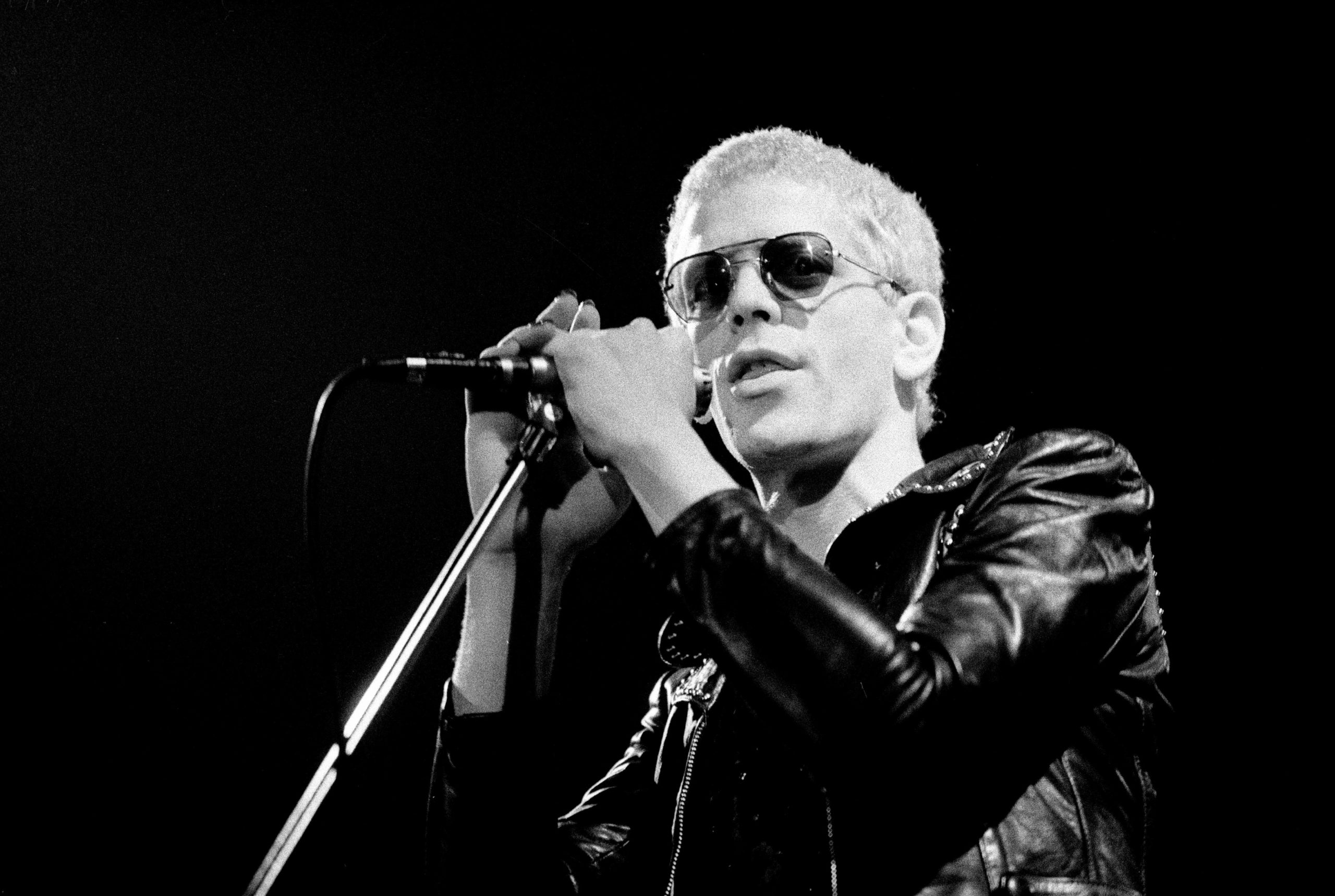

Walk on the wild side: Reed performing live in 1974.

In 1974, Kill Your Sons on Sally Can’t Dance raged both at his family and the “two-bit” psychiatrists whose actions blew away his memory and who knows what else. But Reed’s eyes, sad and reproving, said as much as any song could: that he has always carried the experience with him. Still, he sometimes managed to joke about it, telling biographer Victor Bockris: “It was shocking, but I was getting interested in electricity anyway.”

When John Cale first met Reed, late in 1964, he remembered “a highly strung, intelligent, fragile college kid in a polo-neck sweater” partial to mind games. By then, Reed had graduated from Syracuse University in upstate New York, where he’d studied English and philosophy. When not studying, he spun free jazz records on a late night radio show, wrote letters daily to a sweetheart in Chicago named Shelley, and played guitar in numerous no-hoper beat and folk combos. The authorities kept a watchful eye on him, suspecting drugs and homosexual transgressions. He got hepatitis, most likely after a shared drug encounter with “a mashed-in Negro named Jaw”, an experience that would soon provide the inspiration for a song called Heroin. And between 1962 and ’64, he flourished under a creative writing tutor named Delmore Schwartz.

Schwartz was a speed freak and an alcoholic, Jewish but in exile from faith, tortured by depression and paranoia, and a writer/poet who surrendered himself to his largely autobiographical work. That made him the perfect anti-hero for the Long Island renegade. But by July 1966, Schwartz was dead at 52, remembered only by a handful of poets as a gifted man who threw it all away. Lou attended his funeral. Two decades later, he dedicated My House on The Blue Mask to his old mentor. He was, sang Lou, “the first great man that I had ever met.”

There was something else Cale remembered about Lou Reed: that he wrote “twisted folk” and sang like Dylan, but his songs “seemed sorry for themselves”. His lyrics caught Cale’s attention, unflinching reportage from the dark side of the street, material you’d expect to find in the writings of William Burroughs and Hubert Selby Jr but rarely, if ever, in pop. Before teaming up with Reed, Cale was a fixture on the New York avant-garde, playing viola and with a liking for extravagantly long pieces of drone music. Lou, according to Cale’s collaborator Tony Conrad, was simply “possessed by rock’n’roll”.

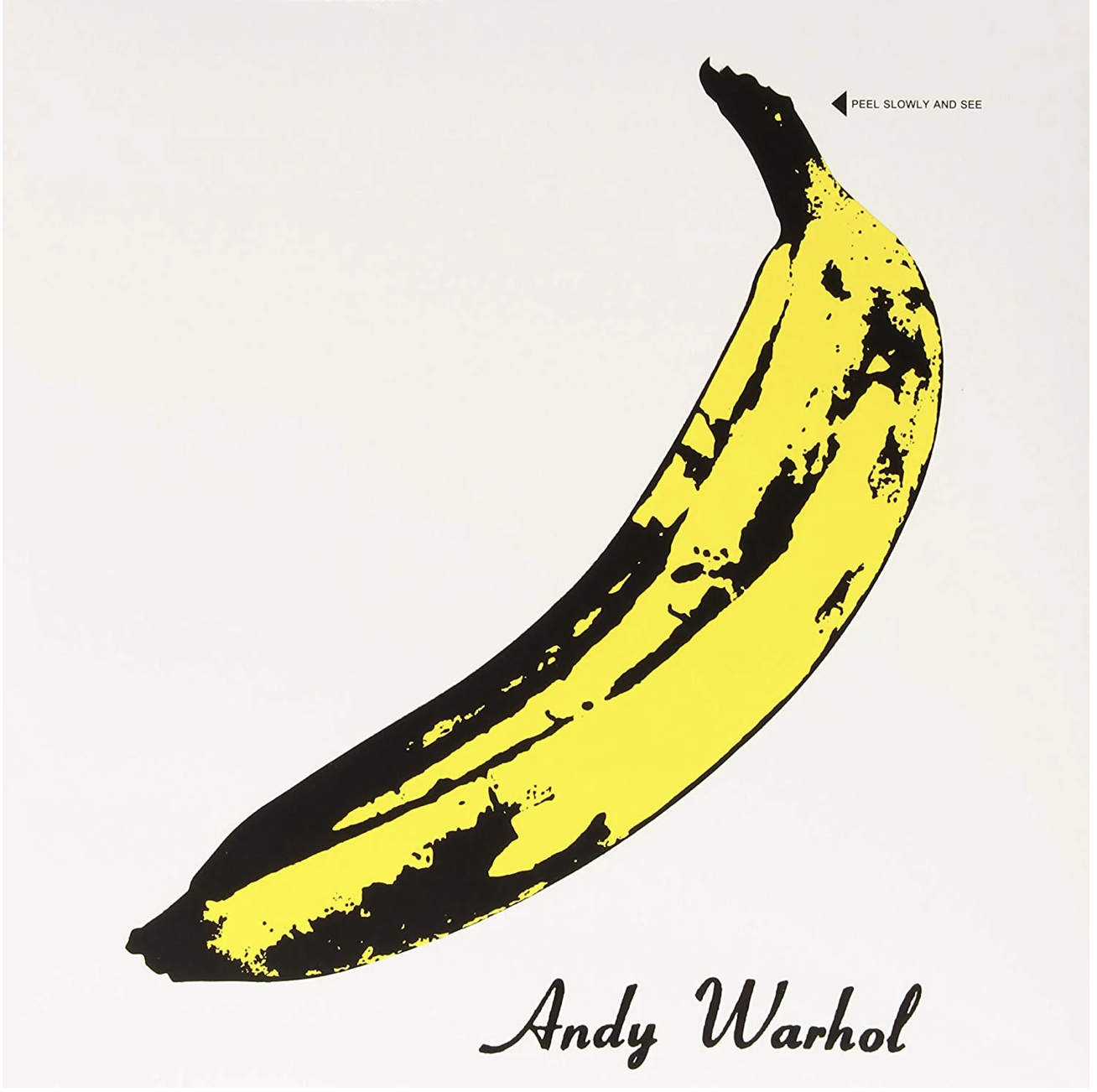

Everything changed for The Velvet Underground in December 1965, when Pop Art controversialist Andy Warhol caught them at New York’s Café Bizarre. Within days, they were a significant element in the menagerie of freaks, artists and ‘Superstars’ who gathered at the artist’s Factory studio.

“Once in Warhol’s orbit, they’d assumed they’d get famous fast,” says legendary A&R man Danny Fields, an eager mid-’60s scenester. “What an acknowledgement to have Warhol create a record cover like that [The Velvet Underground & Nico aka ‘the Banana album’]! The trouble was, it was like a road sign, so everyone saw it as an Andy Warhol thing. But the truth was that The Velvet Underground were a really great band in their own right.”

Writer Al Aronowitz, who briefly managed the Velvets before Warhol breezed in, dismissed Reed years later as “nothing but an opportunist fucking junkie”. He was still bitter. But for all Reed’s admiration for Warhol – who, especially after the artist’s death, he often mentioned, usually uttering the words “genius” or “love” in the same breath – he felt that the artist’s sponsorship of the band was swallowing them up out of existence.

At the height of 1967’s Summer of Love, in a clear act of cultural patricide, Reed dumped Warhol. Some insist it might have had something to do with money, that royalties from the debut album were imminent and the band didn’t want to share them. But mostly the split was fuelled by a desire to be accepted on their own terms.

Nevertheless, Reed knew he owed a huge debt to Warhol. Though he’d been writing about drugs, dark alleys and going insane long before they’d crossed paths, Warhol’s decadent milieu gave him access to characters that would inhabit his work for years. And though it seemed oppressive at the time, Warhol’s blessing and all that went with it invested Reed’s work with the kind of aura that money couldn’t buy. Above all, Lou noted the simple techniques that the artist employed to protect his emotional centre – sunglasses, deadpan façade, and “Er, yes, er, no” answers to prying questions.

While film-maker Paul Morrissey remembered Reed as “an uncomfortable performer” during the Factory era, others have spoken of a far more complicated, confrontational nature. To Sterling Morrison, Reed’s “fragmented personality” meant it was virtually impossible to second-guess his mood. Nat Finkelstein, the photojournalist and The Factory’s iconographer, was far more direct in his assessment to Victor Bockris, telling him that Reed was “about as fragile as a piece of stainless steel”.

The Velvet Underground, 1967: All punk, alt, cult and indie rock start here

Reed’s complex personality also seemed ingrained in the music itself. Whether hissing and spitting his way through Black Angel’s Death Song on the first album, or remixing I Heard Her Call My Name on the follow-up, White Light/White Heat, so that his maniacal guitar solos genuinely assault the senses, it was clear that Reed sometimes regarded his music as a weapon. “One of my finest hours,” he told me in 2009, recalling the impact of those incendiary solos. “Everybody ran for cover…”

The Factory-reconditioned Lou, or ‘Lulu’, was also capable of “spit[ting] out the sharpest rebukes”, recalled Cale. The often toxic atmosphere that pervaded Warhol’s coterie of misfits did wonders in quickening his already acid tongue. Singer Nico, briefly Lou’s lover and added to the line-up at Warhol’s request, put Reed’s anger down to the “combination of all the pills he takes”. As the focus for the spotlight, and much of the band’s publicity, she was often on the receiving end. “Lou was the boss,” she shrugged.

Despite being the dominant figure in the group, Reed still needed to make sure of his own role. Once he’d engineered her departure, he had the exclusive right to sing the songs he wrote. The following year, he offered Morrison and Tucker a him-or-me ultimatum that saw off the increasingly formidable John Cale too. By autumn 1968, there was no doubt that The Velvet Underground was Reed’s band.

After the coup, a calm of sorts – although new songs like I’m Set Free and Beginning To See The Light were highly suggestive of epiphany, even mild euphoria. All the whip-cracking dancers and other non-musical distractions from the Warhol era were long gone. Now Velvet Underground gigs opened with lazily upbeat We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together; instrumental warfare was kept to a minimum; even Heroin was dropped from the set. To ram home the change, Reed came out from behind his dark glasses, wore floral shirts and velvet trousers and let his curly hair grow.

This was, he sang, “the beginning of a new age”. It didn’t last. During summer ’70 sessions for the Velvets’ fourth album, Loaded, Reed was in retreat, and actively encouraging Cale’s replacement Doug Yule to sing, even on the bellwether New Age, a song that underwent a minor lyric change which altered its perspective from one of warm expectancy to abject ruined glory.

On August 23, 1970, towards the end of a two-month season at Max’s Kansas City, Reed walked off stage and quit the band. It came out of the blue. Loaded was going to be Reed’s most accessible outing yet, and new label Atlantic were already talking up Sweet Jane as a potential radio hit. “I didn’t belong there,” Reed later insisted. “I didn’t want to be in a mass pop national hit group with followers.”

That wasn’t the half of it. He was demoralised. Years later, Sterling Morrison confessed that his ex-colleague had simply “gone insane in a very dull way”. There were bizarre rumours that his parents turned up at Max’s and drove him home. What’s certain is that Lou ended up back on Long Island, where he remained for the best part of the next 18 months.

This was Lou Reed’s ‘lost weekend’. He was spotted driving his parents’ Datsun, and apparently did a stint at his father’s office. It is likely he was using the facilities to file suits to claw back his songwriting copyrights, a move that soon had a positive outcome for him. Judging by the poetry he wrote during this period, he was more than ever the deeply conflicted Reed. As a measure of his desire to start anew, he met a waitress named Betty in a supermarket, and promptly declared his love for her in verse form. Other poems testified to self-pity, castigating his “sad and moody self”, announcing his boredom.

Reed’s ennui is reflected in his portrayal of Brian Epstein in that 1971 essay, “praying to resurrect once again the excitement, the glory, and the power”. Lou is under no illusion who the Fallen Knight really is.

“I’m a guitar player who loves feedback, I’m not that complicated…”

Across the Atlantic, in an unfashionable outpost of London, David Bowie had recently recorded an homage to The Velvet Underground, crowning several years of devotion. The Queen Bitch riff sounded like a steal from Sweet Jane but there was one important difference: this one sounded like The Velvet Underground. When Bowie arrived in New York to sign a new contract with RCA, on September 9, the pair met at the Ginger Man restaurant, and it’s quite possible Reed played a few new songs to Bowie in his room at the Warwick Hotel. Around the same time, a ripple of belated praise for the Velvets in the British press prompted the re-release of the band’s first three albums in October 1971. Without Lou having to do a thing, his career was poised for a breakthrough although, as he was quick to point out when we last met, “there was no guiding brain”.

Nevertheless, Reed was happy for the attention. Having cobbled together a set of songs (several dating from Velvet Underground times), he flew to London right after Christmas 1971, and was ready to start work on a solo album for RCA with Richard Robinson producing. Later in January, he was in Paris for a one-off show with Cale and Nico.

It all helped create a buzz, but the flurry of activity hardly set the world alight. The album was recorded with a bunch of disinterested session musicians and managed not to put a photo of Reed on the cover. The gig, billed inevitably as a Velvet Underground reunion, was acoustic, with Lou oddly pudgy and with big Noel Redding hair. This was no snarling Factory misfit raging about his mind being split open. “Pale, pale rock’n’roll,” chided Charlie Gillett in Let It Rock. It was an inauspicious, uncertain return.

Six months later, an entirely different Lou Reed turned up at Trident Studios to record Transformer. “I think he was on heroin,” remembered Trident regular producer Tony Visconti shortly after Reed’s death. “He was just sitting in the corner on the floor kind of nodding off. I remember saying hello and he just looked up and was all glazed over.”

That was the old Lou Reed, maybe worse. Weeks earlier, Reed had walked off the Festival Hall stage on July 8 to the biggest acclaim he’d yet experienced. He was there at Bowie’s invitation, sang three songs from the Velvet Underground catalogue, then promptly stepped back into self-destructive ways. For the next decade, both the public and private Lou Reed ricocheted like a pinball. The ‘thick skin’ he deemed a prerequisite for dealing with fame came to him in many forms – tumblers of double Scotches, powders and pills, but also in his deliberate refusal to stay still as an artist. That, according to the Fallen Knight of yesteryear, had been Hendrix’s downfall, being forced to repeat his act in a “frenzy of self”, and all because “the wretched THEY want it”.

To avoid any such indignity, Reed followed up the success of Transformer and Walk On The Wild Side with Berlin. RCA billed it “The Sgt. Pepper of The Seventies”. Critics and audiences savaged it. Lou’s meticulously crafted rock cabaret soon acquired the reputation as the most depressing rock album in the world.

Berlin exacted a heavy toll on Reed, and his marriage collapsed soon afterwards. His response to its loudly ungrateful reception was to play to the crowd on the live and unremittingly rockist Rock’n’Roll Animal, then mess with it on the funked-up Sally Can’t Dance. Claiming to have slept through its making, he toured it in the States, feigned shooting up on-stage and, hey presto, he scored his first US Top 10 album. It was all too easy.

Rock’s now decidedly sinister imp of the perverse then decided to sabotage his career good and proper. The four sides of feedback and overloaded guitar manipulation that comprised 1975’s Metal Machine Music came close to fulfilling his mad fantasy. Reed was out of control, but seemingly defiant. “My week beats your year,” he boasted in the barely digestible sleevenotes.

“I’m too literate to be into punk rock”

In 2009, Reed was still the proud, unrepentant maker of the most controversial – most would say unlistenable – record ever offered for sale by a major rock star. Was it an act of provocation? “Not at all,” he said. “I was trying to get out of a label contract.” And the real reason? “I’m a guitar player who loves feedback,” he insisted. “I’m not that complicated…”

While Reed was putting his neck on the executioner’s block, a new generation of musicians was emerging in New York that, within the year, would spearhead a new rock revolution that threatened the existence of the old order.

On November 7, 1975, in Danny Fields’ New York apartment, Lou heard the Ramones for the first time. His reaction, revealed for the first time in a highly edited transcript supplied by Fields, offers a unique glimpse of Reed, red-hot with passion for a new cause in rock’n’roll.

After ripping into Television (“I thought they were acting gay to placate me and see if they could get on the tour!”) and his new Arista boss Clive Davis (for passing on Patti Smith), Lou asks, “Can I hear the Ramones?” Fields sticks on demos of I Don’t Wanna Go Down To The Basement and 53rd & 3rd. “That is without doubt the most fantastic thing you’ve ever played to me!” Lou declares. “It makes everybody else look so bullshit and wimpy – Patti Smith and me included, man!”

He then asks to see a photo. “Ah! It’s too perfect! They are their own dream! You gotta be kidding! Johnny Ramone? Oh, leave me alone! How can they not be monsters? Jeez. It’s what everybody’s been waiting for. The Stooges? No! The Stooges weren’t smart. What they did was natural. This is calculated, it’s so insanely perfect.

“He starts every song like that? Twelve songs in the same key and they all start and end the same? It demolishes everything! Can you think of Joni Mitchell now? Or The Grateful Dead? [This] is the glory of youth…”

It was instant recognition and spot-on. But within a year, Reed was bored again. His latest sobriquet, ‘Godfather of Punk’, was not of his own making. The more acclaim he received, the more he wrestled with it. “I’m too literate to be into punk rock,” he raged, while at the same time doing the rounds in all the fashionably grimy clubs.

His legendary mood swings seemed to intensify, too. Velvets aficionado Robert Quine, then guitarist with Richard Hell And The Voidoids, tells a story where Lou, having just seen him play at CBGB, raved about what a great guitar player he was while at the same time threatening to smash his face in.

Becoming one of those living legends exacted a great toll on Reed’s psyche. The title of his 1978 double live set, Take No Prisoners, nailed not just the attitude but, more depressingly, the man. There was almost as much stage banter as there was music, but Reed loved it. “If I dropped dead tomorrow,” he growled, “this is the record I’d choose for posterity.”

Transformers, 1972: Reed’s 2nd, most accessible, solo album

Among its many ‘moments’ was his favourite late-’70s cliche, that “I do Lou Reed better than anybody.” The competition grew fierce. Everyone was banging on Lou’s drum, with his de rigueur look of shades, leather jacket and T-shirt the nearest thing to a punk uniform. When Sid Vicious OD’d, John Lydon blamed it on too many Lou Reed albums.

Punk was going stale, and Lou Reed was getting worse. Both The Bells (1979) and Growing Up In Public (1980) saw Reed propped up with numerous shared writing credits. But something was stirring on the latter. The Mick Rock cover shot depicting Reed in ‘Average Guy’ apparel was a first, that’s for sure.

On Valentine’s Day 1980, two months before its release, Reed married Sylvia Morales. They’d met the previous year, and as the new decade got underway, the couple began to spend more time on their 18-acre rural retreat in New Jersey, reportedly enjoying a diet of nuts and fruit juice and delighting in the landscape. Inevitably, the album had been full of the joys of new love, but one song clung steadfast to his old life. “I’ll go out gracefully, shot in my hand,” bragged Reed on The Power Of Positive Drinking. It turned out to be a parting shot. Months later, Reed gave up booze altogether.

Now committed to sobriety with a conviction that equalled his once unquenchable thirst for self-destruction, Lou was newly empowered. He could do anything. And during the MTV-driven ’80s, opting for survival in a fast-changing rock world was as drastic a move for ‘Cool’ Reed as releasing Metal Machine Music.

He picked up the guitar again for 1982’s The Blue Mask, his best in some time, turned up in ads for Honda and American Express, and even sanctioned the release of some previously unheard Velvet Underground recordings (VU), He also started mouthing off against drugs, that “single most terrible thing”. Lou Reed had gone straight.

This dramatic turnaround in his private life wasn’t always matched on record, though, with 1986’s Mistrial being prime contender for his most shamefaced AOR moment. The deaths of Warhol (1987) and Nico (1988) seemed to provide a catalyst for change, because from this point on, Reed permitted a little more of his old public self back in. It was further proof that he’d become more secure in his new way of life.

The first fruit came with 1989’s New York, Reed’s grittiest album in years, a highly acclaimed song cycle about his hometown rich in detail and buzzing with a new- found political conscience. Apart from once endorsing Jimmy Carter for President in the ’70s, politics was something Reed always shied away from. New York was swiftly followed by Songs For Drella, a collaboration with John Cale based on Warhol’s life story, full of warmth and witty with it.

Reed’s handshake with his past extended to a full embrace when, after burying their differences, The Velvet Underground did the unthinkable and reunited for a full-scale 1993 European tour. When a proposed US jaunt was cancelled, as well as plans to record a new studio album, it was obvious that not every old scar had healed. Reed, now with rimless specs, perma-scowl and resembling an older version of Steve Albini, is believed to have had his mind set on a producer – and wouldn’t back down on his choice, forcing tensions to rise again and split the band.

Since the mid-’80s, Reed – by now an Elder Statesman in the manner of Jagger and Dylan – had been extending his role in public life. He shook hands with Popes and Presidents, picked up awards, established scholarships and got involved in charity work. The cumulative effect of all the changes he’d effected since the early ’80s was that his reputation finally freed itself from the long, dark shadow cast by the Velvets. Perfect Day, from 1972’s Transformer, became his biggest-selling song thanks to a BBC promotional tie-in that went from being a self-serving move on the Corporation’s part to being released for Children In Need. The delicacy of songs like Sunday Morning and Pale Blue Eyes came out of hiding and found new audiences. Ever the contrarian, Reed countered by reviving the spectre of Metal Machine Music and fronting a ferocious improvisation trio. He even turned round the reputation of Berlin by taking it on the road in 2007 with a massive band and choir.

Behind all the reputation building and good public works, the private Reed was increasingly drawn towards matters of the spirit. Speaking to Q’s Mark Cooper, around the time of Magic And Loss, he explained that while the subject of the album was death, its fundamental theme was transcendence. “That’s ultimately what we’re talking about,” he said, “transcending a situation to a higher plane of consciousness.”

His last bona fide solo album was 2007’s Hudson River Wind Meditations, music specifically made for the mind, body and spirit, an immersion in sound that seemed to counter the disruptive energies inherent in Metal Machine Music. It was also a public endorsement of Reed’s deep commitment and understanding of tai chi, a martial practice that he’d made an integral part of his daily routine for the past 25 years. But, just when it seemed as if Reed had opted for the quiet life, he took a left turn, teaming up with Metallica to reaffirm his noise credentials on Lulu – an album based on the plays of Frank Wedekind which divided both his fans and those of his metal sparring partners.

“That’s ultimately what we’re talking about, transcending a situation to a higher plane of consciousness.”

LOU REED passed away at his home in Southampton, New York, on October 27 2013, in the arms of his beloved wife Laurie Anderson with whom he had shared his life for 21 years. His eyes were wide open. With his passing, rock lost one of its warrior masters. Driven by a rare combination of wild forces and intellectual inquiry, he believed passionately in rock’n’roll, breaking down barriers both in terms of subject matter and the sonic spectrum. His gifts went beyond breaking new ground. For all his provocation, he also managed to leave behind some of the most disarmingly elegant melodies in pop. But above all, Lou Reed didn’t just sing; he spoke to people, re-making himself several times over in the process.

Back at Trident in September, during our last encounter, the giant-sized book of photographs fell open at a random page. “This is a particularly interesting pose,” remarked Lou. “I don’t even look like I’m a real human. Isn’t that amazing?” Feeling brave I asked: “Doesn’t that mean the photo’s telling us a lie?” “No, not telling a lie,” he countered, bringing the conversation to an end. “Passing through some kind of warp. That’s part of the fun.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 242.

Images: Jorgen Angel/Redferns; Getty