Mojo

Presents

Laurie Anderson

A Midwest violinist-turned-New York performance artist, O Superman shot her to fame. Now, as Laurie Anderson puts her philosophy of life on film, and comes to terms with husband Lou Reed’s death, she says “All we have is now.”

Interview by Andrew Male

“I’m sorry,” says Laurie Anderson, “When I’m away from my home I kind of take my office with me.” She is sitting in a high-backed designer leather chair in the corner of a cluttered Warner Records anteroom, scrolling through the e-mails on her phone. Tonight she has a few hours off and might take herself to Foyles bookstore, but for the rest of the time she’ll be stuck in what she calls “the film festival rut: screen your film, talk about your film…” as she promotes Heart Of A Dog, a funny, sad, lyrical cine-essay that moves from ruminations on the death of her much-loved rat-terrier Lolabelle to reflections on storytelling, language, identity, memory and loss.

Anderson’s tour-look is relaxed and Eastern, dark silk jacket, linen trousers and trainers, and her words are delivered with a melancholy lightness, her eyes wide and bright, her smile puckish, suggesting that it’s no biggie, this European festival rut, just something that goes with the job, after thirty-plus years as a multi-media performance-art avatar, monologist and recording artist of rare and strange beauty.

It’s the same soothing yet questioning tone we first heard on Anderson’s dreamlike 8-minute 1981 single O Superman – debuted on John Peel’s late-night BBC Radio 1 show – that led to a signing with Warner Bros Records, briefly propelling the then thirty-three year-old New York-based performance artist into a heady world of pop stardom. The fame eventually settled down into something more convenient but the song never really went away. It was under the surface of albums like 1995’s Brian Eno-produced Bright Red, in which Anderson attempted to comprehend America’s war in the Gulf and reappeared in her live New York performance on September 19, 2001, where lines such as “here come the planes/they’re American planes” hummed with their eerie prescient power, confirming what Anderson has always said, that “we’re all still stuck in the same war.” And it recurred in the short evening performances that followed her most recent art installation, Habeas Corpus, at the New York Armoury in October. Here, a live video image of Mohammed el Gharani, one of the youngest Guantánamo detainees, was projected onto a sixteen-foot-high sculpture of a seated human form the size of the Lincoln Memorial.

The drone score for Habeas Corpus was composed by Lou Reed, Anderson’s former husband and partner for over 20 years before his death in in 2013, and it’s Lou and Habeas Corpus and the new film that our conversation keeps resetting to today, amidst matters of the past and the future, bearing out the message that Heart Of The Dog plays out on, bound up in a Reed song from 2000, Turning Time Around. “He gets the last word,” says Anderson, “and it’s right to the point: don’t go looking to the past with your regrets, don’t go to the future and how much better it’s going to be. All we have is now.”

How did Heart Of A Dog come about?

It was a commission from Arte, the French/German TV channel. They said, Can you make a film about your philosophy of life? I said, I don’t have one. And if I did I would not put it in the shape of a film and make you watch it. Well, the producer had come to [Anderson’s 2012 performance piece] Dirtday! and he said, ‘You had those stories about your dog. Put those in,’ and I said, OK. Then I added a few related stories, then asked a few questions about how you tell a story, and what happens when you repeat your story, or forget your story, and then, in the end, it’s my philosophy of life. They’ve tricked me into it.

It references The Tibetan Book Of The Dead a lot….

I began to study The Tibetan Book Of The Dead after Lolabelle died. It became very personal because it’s all about what I do as an artist anyway. How to be aware. That’s it. You’re not even asked to believe anything particular. That’s an amazing approach to things. My family’s religious background was one half Southern Baptist, the born again stuff, and the other side was Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant which was just a be-nice-to-people religion. That’s it, just be nice. So, I got a little smattering of different approaches.

The film is also a meditation on loss.

It’s about death in general. I have only recently started to count the number of people who die in this film. But even though love and death are themes, the actual theme is story construction, like why do we tell stories and where is it that language become fallible and images have to take over. That’s one of the reasons why the second story in the film is my mother’s deathbed speech. She was a very proud person and very formal so she waited on her death bed until all eight kids were there and she almost sort of stepped up to the microphone and said, Thank you all for coming, and then she gets a little distracted and starts talking to the animals she sees on the ceiling, and in this way that you can watch the words just sort of ripping apart. It was one of the most moving things I’ve ever seen, because language is completely inadequate to the task of saying goodbye.

I don’t want to make a trite leap, but this film ends with a Lou Reed song, the sound of Lou’s voice…

That’s not a trite leap. He didn’t use any reverb on his voice in that song and it’s very, very real. Very conversational. Very engaged. And I loved that he made that equation of love and time being the same thing.

How did growing up in the Midwest, in Illinois, shape the stories you told?

Well, Heart Of A Dog is also a film about the sky, as it represents freedom and fear. And inHabeas Corpus, the whole Armoury is turned into the night sky. It became a context for how we see our own freedom because it was for me as a child. A very, very flat place, with a dome of sky, that was the dominant thing where I grew up and even now I like really super-flat places like Holland. I see mountains and I feel hemmed in. Other people go, ‘That’s nondescript.’ I say, what do you mean? It’s sky-rich.

You came from a big family, seven other siblings including twin brothers. In Heart Of A Dog you tell a story about wanting to be noticed, of doing a back flip off the swimming pool high board and missing the pool. You broke your back, you were paralysed, doctors said you’d never walk again, and it took you two years to recover…

Yeah. I was the second oldest and so my job was to take care of a lot of them. It shaped my life, like anybody who has that. While I was in the middle of making Heart Of A Dog my older brother sent me these cartons of old 8mm film. Family films. I was really busy so I just reached in and transferred a couple and suddenly there’s my little brothers in a stroller, there’s me ice-skating, there’s the lake, the island, Oh my God. I called my brothers and said, Remember that time I almost drowned you, when the stroller went under the ice? Yes, we do! They’re twins so they have like an outboard brain and they were two and they remember that. And they said, You’re not going to put that in the film are you? I said, Do you mind?

“I’m not trying to colour outside the line on purpose. I just find it more interesting.”

Ice skating is central to one of your earliest performance art pieces, Duets On Ice. You wore ice skates frozen in blocks of ice and played a duet with yourself on a violin where the bow hair was audiotape and the strings were a tape head. The piece ended when the ice melted…

Ice skating and frozen lakes was my life as a child. I came from a frozen world. Every winter there was snow up to the height of the ceiling, and so much of my life was being dazzled by the sparkle of winter. That and the sky are the things you carry with you.

You were studying classical violin from the age of five….

Yeah. my parents wanted a family orchestra.

The Midwest Von Trapps?

Hur. Not quite. Let’s not go that far. We didn’t… oh, we *did* wear matching outfits! What am I saying? Oh dear. We wore navy skirts and red sweaters. Nice.

You were an undergraduate at Mills College in California which became The San Francisco Tape Music Center, home to Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, Terry Riley… Did your world cross over with theirs?

When I was there it was more Pablo Casals in residence. I was doing chemistry. I was pre-med. I had stopped violin. I realised I wasn’t really good enough. I liked the idea of medical school a lot but I was only one semester at Mills. I hated it. I hated every minute of it because you had to wear a long skirt to dinner on Wednesday and that put me off the whole thing. I was just disgusted by that. I’d gone to California to be as far away from the Midwest as possible, so then I just decided to go to New York instead and in the middle of studying chemistry and botany, I realised I actually liked doing the drawings more than I liked getting the information right. So I thought maybe painting is more for me.

One of your earliest performance pieces, from 1972, was the Institutional Dream Series, where you slept in public places to see if specific sites influenced dreams. Heart Of A Dog begins with the recounting of a dream. Dreams seem integral to what you do…

I trust that world. A whole lot of things come from that world. One of my favourite stories Mohammed recounts in Habeas Corpus is about a detainee they were interrogating and he told them about a dream he’d had where a submarine came to Guantanamo to rescue everyone. Well, that night, Guantanamo Bay was filled with helicopters and ships, looking for the submarine that he had dreamed about.

That’s so creepy. The CIA are looking for plots against them in our dreams.

We make plots in our dreams. It’s an obvious thing to say, but many of our fears and hopes are expressed in our dreams. When you think of what you’re actually talking about, it often has nothing to do with what’s really going on. I put some really fast words up on the screen in Heart Of A Dog, [to represent] those words that go around in your head, that you never say. It’s like talking to that person inside you, the silent witness, the person who’s been there all the time, and to whom language sounds a little bit stupid. You’re using them right now, as I am, as we’re having this conversation, that silent witness is analysing it and thinking this, but not saying anything ever. That’s why I wanted you to read this fast succession of unvoiced words. It’s coming in a different way into your mind. I invented a computer program to do this, ERST. I don’t know why I gave it a German name. I think it stands for Electronically Reproduced Simulated Text, or something horrible like that.

You’ve always done this, inventing new strange instruments like the tape bow violin or the talking stick. Is this always a means to an end – I want that sound that doesn’t exist – or an end in itself – the beautiful-looking art-piece?

A little bit of both. They’re a bridge for me between sculpture and performance. They’re hybrids. My work often is. Habeas Corpus is sculpture, performance and film. I like weird hybrid forms. I’ve never really fit very easily into a category because they have these uncomfortable elements that don’t fit. I’m not trying to colour outside the line on purpose, it’s just… it’s interesting.

Anderson and husband Lou Reed

In 1976, you were briefly in a band with Arthur Russell.

He was in my band. Cello and drums. I loved Arthur’s music. We got along really well. We didn’t think that it was because we were [both] from [the Midwest]. It’s funny what happens when an industry dies, a record industry. It has crumbled, that empire, and with it the ability to sit around for a year and make a record. There isn’t really a substitute for spending that amount of time on something. You could do big things. But I try not dream of that. Just go and make something really simple with a pencil.

I also read you were Andy Kaufman’s straight man at the end of the ’70s. When he got to that part of his show where he said “I won’t respect women until one of them comes up here and wrestles me down.” That was your job, to wrestle him.

Yeah. And he wasn’t pretending. It wasn’t scary. Maybe metaphorically scary. I don’t think I was ever really scared. I think if he thought he was going to hurt anyone he would have absolutely stopped. There was metaphor in everything Andy did. On the other hand, he was very hardcore and believed in everything he did. He was a kind person, and funny, but he loved using doubt and violence and fear and confusion. He was a master of all of that, of creating that and bringing it out. We’d go on field trips to Coney Island to test out his theories. We’d go on rides like the Rotowhirl, where the bottom would drop out and plaster you to the side of the spinning cylinder, and right before the ride would start he’d be saying, “I don’t think this ride is safe.” People who were about to have fun on the ride, a lot of them got off.

You recorded your 1981 single O Superman through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and pressed up just 100 copies. John Peel played it on Radio 1, you were signed to Warners and it went to Number 2 in the UK singles chart. Do you ever wonder what might have happened if John Peel had never played it?

I think I had a fairly anthropological interest in that. Or tried to. When you get something that you didn’t dream of, it means a different thing than it would if you’d always dreamed of having it. I knew this would be dangerous if I wanted it to go on and on because this was a quirk of fate and it’s like, even now, I’m the kind of artist who wants to get smaller rather than bigger. I don’t ever want to open the Berlin office.

You perform O Superman during Habeas Corpus’ evening shows. Those lines “When love is gone, there’s always justice. And when justice is gone, there’s always force” really resonated with audiences. Similarly, when you played O Superman at Town Hall in New York City in the week after 9/11 and sang, “Here come the planes / They’re American planes,” you said you suddenly realized you were “singing about the present”. Does it spook you out, how much that song continues to accrue meaning?

No it doesn’t, because we’re in the same war. Most people don’t recognise that. And it’s working kind of the same way. The same things keep breaking down, the same questions keep being asked. And force, justice and love are still major themes.

At the height of your popular attention, you made one of your biggest multi-media productions, the Home Of The Brave concert movie. There’s so much going on in that film, so many people on stage… Were you trying to hide from pop stardom behind all that spectacle?

I’m not sure I wanted to hide. No. During that time, and part of it comes from being a snob, when I went out to Warner Brothers to do my eight record deal, they sat me down in a room and said, “I want you to meet the other artists”, and there were these guys like [mimes slouchy, gurning, nose-picking urchin] and I was like, Who are these guys? ‘Artists’ for me was like Duchamp. But they spoke about “the artists” with heavy quote marks around them. Wow, you’re being so cynical. We’re your marketing tools. We’re not the artists.

On the other hand, Warners was an incredible label. They actually really liked singer-songwriters. They supported them. They supported me. They said, “We like you music and we’d like to put it out,” and I thought, OK, why not? What is the downside of this? Plus, the other part of the snobbism was that I didn’t like that artworks cost so much and I liked that anyone could buy a record. I got a lot of flak from the art world for signing with Warners. They were like, “You sold out. Why did you do that?” It only took about four or five months before it was called ‘crossing over’ and everyone did that. In the end I was happily floating between both worlds but I never quite belonged to either one.

One single from Home Of The Brave, Language Is A Virus (From Outer Space), was inspired by a line, a concept in William Burroughs’ The Ticket That Exploded. Was he a big influence?

Definitely, because he really made me laugh. That guy was insanely funny. And dark. I toured with him and John Giorno on the club circuit in 1981 and we had a great time. It felt very vaudeville because Bill would always bring his cane and… wait a second… he brought guns. And he would go out and practice. In the back. That bothered me. That he liked guns, and that he didn’t really like women. Those were the two things that put me off a bit. Otherwise, I loved him, because he was an old coot and hilarious and really cranky. And I have a real attraction to cranky people. I don’t know why.

Am I allowed to mention Lou Reed at this point?

Oh, you are. You are. What makes you so cranky? I’m interested in that.

“When your partner is gone part of you goes with it, but part of them stays too… Lou is still a lot more real than many people I know, because he came to play.”

In 1991 you interviewed John Cage for a Buddhist magazine. Another influence?

More twins. Cage and Burroughs. Light and dark twins. I really fell in love with [Cage] in the last year of his life. He made a huge impression on me. So many old people are angry, bored and he was not like that for one second. He almost reminded me a little bit of the happiness of a dog, whose mouth is open, he’s looking around, Wow! He was dazzled by things, and that is probably the thing I most admire in humans, their ability to be dazzled. And he really was in weird circumstances. Merce [Cunningham] had left him, he’s by himself, it’s harder for him to go places… He said, I can’t pick up my suitcase. So I said, I’ll come with you! I was so happy to spend time with him. He was beyond inspiring. His ability to see and appreciate the world as music, and as a completely finished artwork, I think about that all the time, and his ability to be in the present and not be worried about something or projecting something.

Tracks like Night In Bagdad and the Cultural Ambassador on your mid-’90s albums Bright Red and The Ugly One With The Jewels were direct responses to the Gulf War. That seemed to have a major effect on you. It was a multi-media war.

Well, all the wars. But, yeah, sure, it had its own music, its own graphics. It’s like we’ve been saying, the one who gets the best focus is the one with the best story. Do you like the story, do you like the music that goes along with it…

One of your biggest productions was 1999’s Songs And Stories From Moby Dick. The album based on that show became something else entirely, 2001’s Life On A String, and you later said, “If you ever get any idea about doing an opera based on a book you love, don’t do it.”

Yes, and I am so serious about that.

Did you get swallowed up by it?

Yes, just like a whale. I was the smaller fish. I was too worshipful. I loved it too much. That made me too shy and careful. You can’t be shy and careful if you’re going to carve up a whale. I wish I hadn’t done that.

You seem to have this pattern though. After a huge project like that your next project is always stripped back, spare, simple…

Yeah. It’s a question of energy more than anything else because I like to make these beautiful simple things. Like… I’m doing these drawings for this show in Switzerland and… It was in the middle of the summer and I was kind of in trouble from Habeas Corpus. I had to get some therapy because I couldn’t get these pictures out of my head. Do you remember the first time you saw the pictures from Abu Ghraib? This combination of pornography and violence? What is that? And you just can’t get those images out of your head? That’s what happened to me.

One of your stranger commissions must have been when you became NASA’s first (and last) artist in residence in 2003. How did that come about?

Just a phonecall. Why they thought I would be good PR for NASA is beyond me. It was definitely a PR move to get NASA into the public awareness more. Behind that was this idea that its military applications had become dominant in the public imagination, that they were just making rockets and shields and weren’t looking out any more so much as looking down and spying on people and creating fast weapons and that’s very true. They didn’t really know what a NASA artist-in-residence did, so I just became a fly on the wall looking at them.

You don’t need NASA’s budget to make art. You can make visionary art, dangerous art, with a pencil and paper. Artists tend to forget that these days, especially now the Russians are in the market. You notice how many more works have gold dust or diamonds encrusted into the canvas. Extra added value – that’s a nauseating development for me. But I got to poke around in the corners [at NASA] and any time you get to do that is great. This is what I love about being able to do what I do. Without war, I’d never have been friends with Mohammed, who’s not an Al Qaeda operative, but a goat-herder from Saudi Arabia. War gave me the chance to meet this person.

Was that the thinking behind 2003’s Happiness? You prepared for that show by taking a job at McDonalds, working on an Amish farm, Zen river-rafting…

Yeah, get out of my rut. That’s what I should do. I’m in a kind of rut right now. Do you have any good ideas?

Your work is about how you look at the world, and how that changes us you. After Lou died you spoke very eloquently about his life and his passing. At the 30th Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony this year you said his death propelled you into “a magic world where you finally understand things that were complete mysteries up to that point.”

Did I say that? Well, that’s true. I have not rowed my boat back from that. I probably never will, because it’s too wild, and I’ve met a lot of people who were suddenly very absorbed in a partnership, and then your partner is gone and part of you goes with it, but part of that partner stays too. It’s a very, very weird thing to be part of and it becomes a very real thing. Also, when your partner is a really real person the way Lou… Lou is still, I have to say, a lot more real than many people I know because, he came to play. He was not goofing around.

What next?

Who am I? What am I? Those questions are always in the background of what I’m doing. And giant landscape paintings. I feel the need to make something enormous and still.

THE ANDERSON TAPES

Essential Laurie, by Andrew Male.

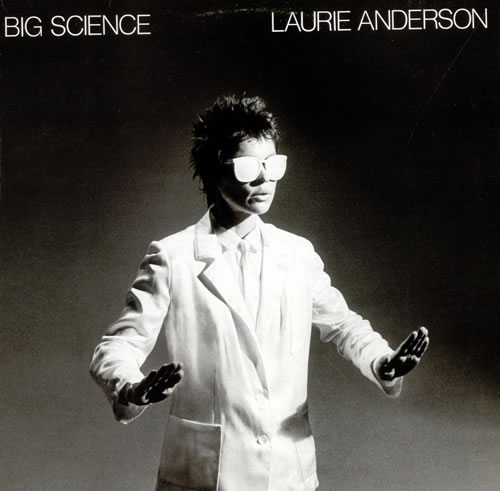

The First One: Big Science

(Warner Bros, 1982)

A flinty distillation of United States I-IV, her eight-hour multimedia performance-art epic about the U.S. military industrial complex, Anderson’s major label debut is a surprisingly moving and groovy collection, somewhere between minimalist post punk electronica and a comic Robert Wilson spoken-word opera about plane crashes and dreams of falling in post-war America. Also, U.S. pop’s love affair with Autotune can probably be traced back to Anderson’s eerily seductive use of vocoder on this LP.

The Ambient One: Bright Red

(Warner Bros, 1994)

“I learned something important when I worked on Bright Red,” said producer, Brian Eno, recently, “I said, what do I really like here? I really like her voice. So I just listened to the voice until I wanted to hear something else happen.” As a result, Bright Red is Anderson’s most spare and spooky LP. Written in the wake of the first Gulf War, it is an hypnotic, unsettling listen, like some deep, long, waking dream on “this tightrope made of sound”.

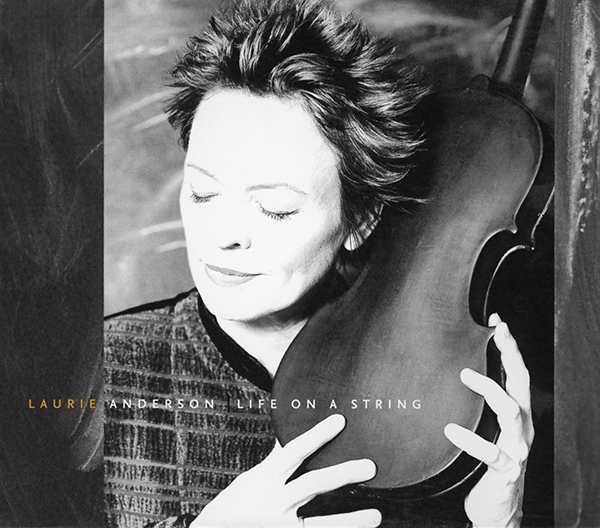

The Diverse One: Life On A String

(Nonesuch, 2002)

Originally intended as an audio document of her vast, impressionistic 1999 performance-art piece, Songs And Stories From Moby Dick, Anderson’s sixth studio LP became something else entirely: three numbers from Songs And Stories plus some of her most honest, emotional and stylistically varied compositions, including collaborations with Bill Frisell, Mitchell Froom and, on the sonically unsettling One Beautiful Evening, her new boyfriend Lou Reed.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 266

Images: Tom Oldham, Getty