Mojo

Presents

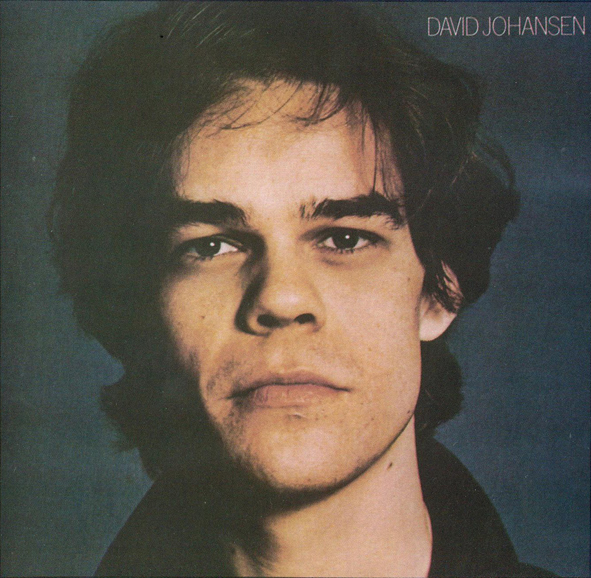

David Johansen

Amid fallen friends and mixed returns, the New York Dolls’ lipstick lothario gave “mock rock” its heart and soul and, refreshingly, he regrets rien. “History is pretty much a fiction,” reckons David Johansen.

Interview by Alan Light

DAVID JOHANSEN SITS ON THE COUCH in the living room of his wife’s walk-up apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The décor can only be described – in the words of one of his songs – as funky but chic. Scarves and wigs are draped over lamps. LPs by Arthur Prysock, Machito, Bohannon are on display. Black-and-white photos of Dolly Parton and the Brian Jones-era Rolling Stones adorn the walls. Johansen himself puffs on an e-cigarette and ponders the notion that after more than 40 years of making music as the singer of the pioneering New York Dolls, an acclaimed solo artist, and as lounge-lizard alter ego Buster Poindexter, he’s currently juggling all of these configurations as ongoing concerns.

“Well, my life is an ongoing concern,” he says with a chuckle. “I’m very concerned about it.”

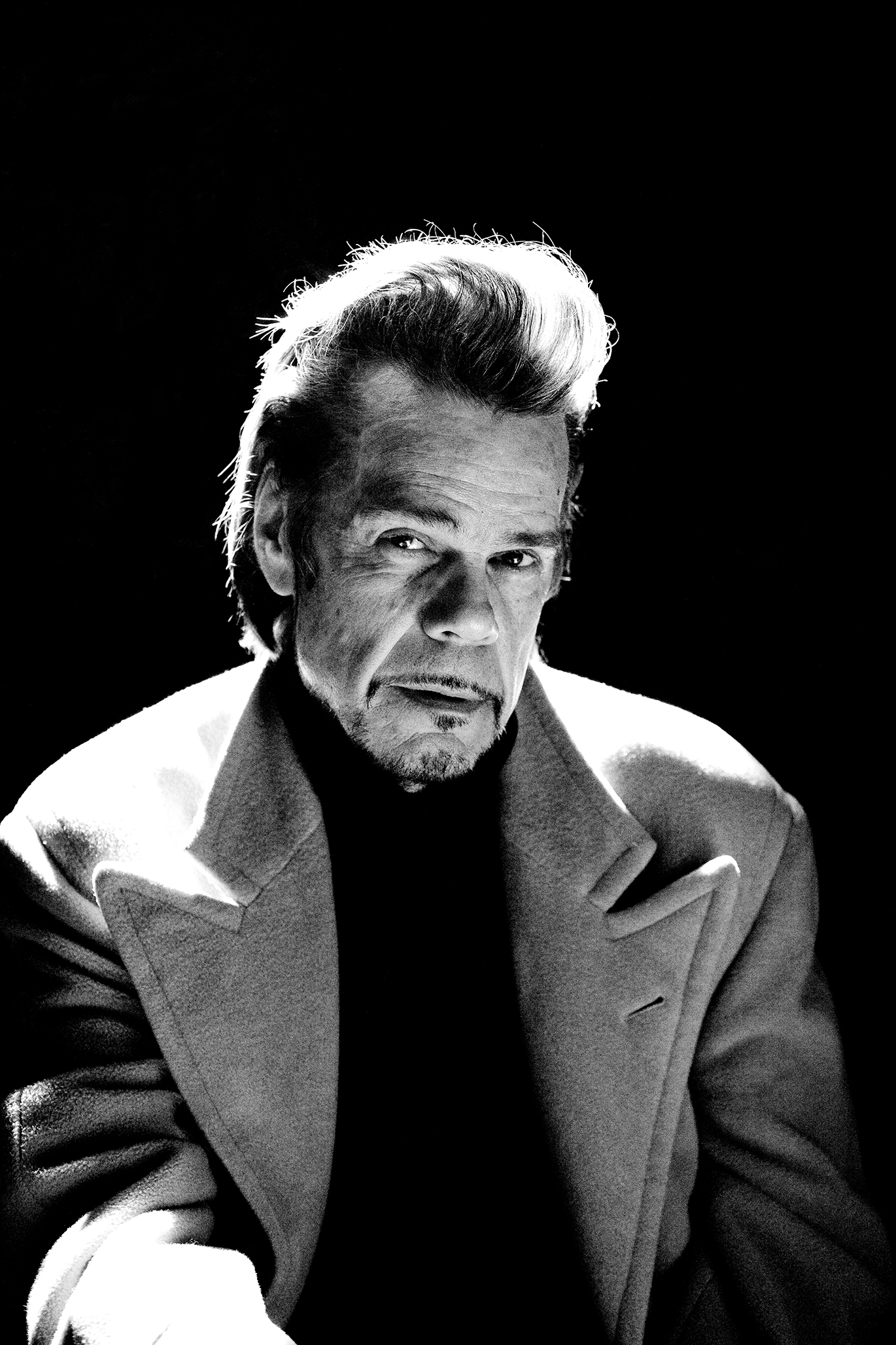

In 1971, the Staten Island-born singer teamed up with Johnny Thunders, Sylvain Sylvain, Arthur ‘Killer’ Kane and Billy Murcia to form the New York Dolls. The band’s stripped-down, balls-out sound – rooted in the groove and swagger of Chuck Berry and girl groups rather than the boogie’n’blues jams prevalent at the time – plus their outrageous, gender-blurring fashion sense helped pave the way for punk and glam. But the Dolls were beset by chaos. Murcia drowned in a bathtub following a drug overdose on the group’s first trip to London (he was replaced by Jerry Nolan), and their two albums – 1973’s New York Dolls and 1974’s Too Much Too Soon – flopped commercially. By the time punk’s moment arrived in 1977 the Dolls were no more.

Johansen, however, never slowed down, juggling musical projects and an acting career that included memorable turns in 1988’s Scrooged and, more recently, HBO’s prison drama Oz. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, the surviving Dolls (Thunders died of an overdose in 1991 and Nolan of a stroke the following year) reunited at the request of superfan Morrissey when the ex-Smith curated the 2004 Meltdown festival. A live album and a touching documentary were released following the triumphant show and, despite Kane’s death soon afterwards, the Dolls went on to tour and release three more albums.

Perhaps it’s just as well, but Johansen is sanguine about a career that’s more succèss d’estime than box-office blockbuster. “The less you try to accomplish, the better it is, ” he says, “the more loose, the more musical, the more fun. When people start getting serious about it, then it’s not really conducive to making good music.”

What’s the first music you remember hearing?

I think I heard Fats Domino or something in my father’s car. My father was a very musical guy, he sang – my mother sang, too, but my father sang in front of people. I have five siblings, so there was always a lot of music there, and I kind of took it for granted. I would play my brother’s records, much to his chagrin. I would go into my room – really the boys’ room – and by listening to music, I could get away from the politics of the household for a while. My brother is five years older than me and when I got old enough to use the record player, maybe six or whatever, he was digging some pretty deep doo wop. He was into the Diablos and things like that.

When did it call out to you as something you wanted to be involved in?

My time was so consumed as a child that I rarely thought about the future too much. I dug singing and dancing, though. I was maybe 13 and I started really digging Lightnin’ Hopkins and Howlin’ Wolf. I liked a lot of other things, as well; I like so many different kinds of music from different places in the world that it’s hard to keep it all straight. It’s all in this kind of primal musical ooze in my head. But I would get a record and sing along. I always sang along with The Platters, singing The Great Pretender and those really operatic songs, and Wilson Pickett, stuff that came out when I was coming of age. And then I got into wanting to perform it.

Did that seem attainable? It’s a long way from Staten Island to Lightnin’ Hopkins.

We used to have Hoot Night at the Jewish Community Centre. Kids with guitars would go to this little auditorium and get up and do numbers. I would do, like, Black Betty in a basso voice. It would be outrageous, but they would clap, “Very nice… now I will sing A Maid Of Constant Sorrow.” So I was into that, and then the guys I hung out with on the corner started talking about how we should have a band. One guy would say, “I’ll be the bass player.” One guy would say, “I was in the drum and bugle corps, so I’ll be the drummer.” And I just thought, “Well, I’m going to be the singer, because I’m not gonna have these equipment schleppage issues.” They would push the stuff in shopping carts, and I would show up with a harmonica in my pocket.

So we started up, very rudimentary, doing In The Midnight Hour and songs like that at the Battle Of The Bands, at the church or whatever. We were called The Vagabond Missionaries. You can say, “Oh, I knew that I was going to be doing this forever,” but I never really thought about what I was going to be doing, I just did. Then, when I was about 15, I went to Murray The K’s show and Mitch Ryder came out and he wrecked the place. Something happened in that moment where I thought, “I want to be in this scene and be with this kind of people.” If there was one cataclysmic moment, that was it.

How did you hook up with the guys who became the Dolls?

I started living in the East Village when I was 17. I was working at this store on St Mark’s Place where we used to, like, cut the Budweiser logo off a beer can and then fix it like a pop-art earring. In the basement, we would do mail order, cutting that stuff up and mailing it to Cleveland or whatever. And the owner had all these garish, kind of lurid costumes hanging all over the place, all these boas and rhinestone outfits and stuff like kings would wear in some kind of fantasy. It turns out that he was making costumes for Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company. So I started going around to where they would rehearse and getting involved in that, playing guitar or doing the sound and lights. Sometimes I would be a spear-carrier or something. I would see the cats walking around on St Mark’s and we had a similar aesthetic that made us notice each other.

There was a cat who lived in my building from Colombia, and he knew Billy, and said he knew these guys that were looking for a singer. So I said, “Yeah, I’d like to check that out.” One day, Billy and Arthur came to my door and said, “We got a band.” As I recall, it was on 6th Street, and I think John [Genzale, aka Thunders] had a place on 10th Street and we went over there and started playing and then we were like, “OK, let’s have a band.” They all knew Syl already, but he wasn’t there that night; he was in Europe somewhere. He showed up one night from the airport, with a carpet bag and a guitar. He plugged in and I thought, “Now this is really perfect.” He had a very swinging way of playing, which we needed to make that thing balanced just right.

Was the Dolls sound identifiable from the beginning?

The whole thing with the Dolls, there was nothing really manufactured about it; it was just us doing the best we could do. It wasn’t like we would talk about what we were going to sound like or what we were going to look like or anything, we just kinda did it. We would play and people would say, “You guys are great,” and we’d say, “Hey, people like it, let’s just keep playing.” At that time in the East Village there was a lot of burgeoning liberation movements going, so we became the band for those people. When we played Mercer [Arts Centre] it was a place for all these people who saw each other on the street but didn’t really know each other. A lot of them went on and did really great things, so we were like the band of that scene for a while.

“There was nothing manufactured about the Dolls; it was just us doing the best we could.”

Were there bands that you looked on as peers? Were you looking at The Stooges or anyone as doing something comparable?

I don’t think I would compare like that; maybe some of the other guys would. I would see The Stooges and go, “Wow!” But I wouldn’t compartmentalise or anything. At that time we knew what we didn’t want to be, but we didn’t know what we wanted to be. There were certain bands I really liked in the late ’60s. I thought Big Brother & The Holding Company was a really great band. Not on purpose, but I think we sounded a little like them – faster, but sonically some similarities there.

How do you feel the recordings of the Dolls stand up?

It’s funny because when we got back together in ’04, I listened to all the records and I thought, “These fucking records are great.” They don’t have dating tells on them – sometimes you hear a song and go, “That’s an ’80s record,” but when you hear that, it could be from any decade. I guess because there wasn’t anything else quite like it.

At one point, you said some really negative things about Todd Rundgren’s production on the first record.

Maybe I did, I don’t remember. I might have been intoxicated. That record happened so fast that Todd probably had a lot of pressure on him from everybody in the band, so it would be like producing a lot of people at once. I like that record. Maybe at one time it was kind of the rap of the day, to say, “This sucks, that sucks, you suck…”

Malcolm McLaren managed the band for a while. Tell us about that.

There’s not a lot to tell. We knew Malcolm because he used to come to New York and be in these trade shows, and we were always trolling for clothes. All the people were showing their wares; you would go from room to room and people would buy the clothes for their stores. But on the last day, nobody wanted to schlep their stuff home, so they would sell it really cheap, so we would go down there and check out the stuff, and that’s how we became friends with Malcolm.

He was going through some kind of situation at home, so he came over and started getting really energetic – OK, boys, we’re going to do this and that, and that was a period of maybe two months. He had a lot of really good work habits. He would make charts and lists of things to do and then cross them off when they were done. Once he came over with all these red leather clothes, which we had ordered, and we all tried them on, and me and Syl wrote the song Red Patent Leather.

So you’d already put the “red” idea in motion? Because it’s usually told that he imposed this concept on you.

No, it was us. We said, “Let’s put up a Communist flag, and we’ll make it a Communist party.” We thought that was really funny. I think he said, “I’ll make red party favours,” or some- thing. But he wanted to have a band, so I think when he went back he told all those guys hanging around his store, “Oh, I did this, I did that.” That’s how showbusiness works.

Did the image, drugs and tragedy overshadow everything else about the Dolls?

A lot of people conflate when the Dolls were around and five years later. When we were around, yeah, everybody took drugs, the whole neighbourhood did, but nobody was strung out or anything. Those cats started getting strung out a little later, and then people superimpose that. [Famed NY scenester] Danny Fields is fond of saying there is no history, there is no truth. History is just what it becomes; it’s pretty much a fiction.

I know John got into smack and saw God and he was no quitter, but that wasn’t the scene for the majority of the time we spent together.

But as the drugs came in harder, for Johnny and others, that must’ve been hard to watch.

I remember we had a couple of incidents with John getting too high – but we all got too high. Everybody would get drunk, fucked up, it would always be somebody. But we were like a gang, so it was OK. We didn’t have a very commercial or businesslike outlook on things. No one ever took us in hand and said, “Boys, boys…”

I remember that Malcolm helped Arthur go to a dry-out clinic one time, and I didn’t even know that those things existed.

Jet Boys: New York Dolls’ (l-r) Jerry Nolan, Sylvain Sylvain, David Johansen, Johnny Thunders, Arthur Kane in London, November 1973.

What was it like seeing the punk movement starting up?

It wasn’t a movement until it was over. When the Ramones came out and Punk magazine and all that, it wasn’t the punk scene, it was just art or whatever. There were so many different groups when the CBGB thing came along, Blondie and Talking Heads and a lot of great bands that didn’t really sound anything like each other. They didn’t call it punk in ’76 or whatever. Later they started calling it punk, and then it became this rigorous, almost military thing: “You play these three chords and this beat and if you don’t play that, you’re drummed out of the corps.”

You didn’t think, “We did all this already!”?

No, I used to go [to CBGB] all the time. Those people were all my friends. When the Dolls were playing, those were our friends saying, “Oh, we’re going to make a band!” So no, that never crossed my mind. I don’t really think like that.

McLaren said that the Sex Pistols were really just imitating the Dolls, studying each one of you and copying it.

You know, when we heard the Sex Pistols record, I thought, “That guitar sounds a lot like Dolls guitar.” I just kind of assumed that’s the way things were going. But everything that you do, you took from someplace else. Each person has all these micro-elements of things they dig floating around in their brain and when they put forth, it comes out as something else. So that sound definitely became part of the recipe, and it stuck out because the guitars and the words in the Dolls songs were not like the records that were going around at that time; there wasn’t really any bands that were doing that. MC5 had that heavy thing and they came before us; we were inspired by them. But there’s so many things – “I like this group because of that guy’s shoes, I like the hair on that group…”

Did you have a sense of what you wanted to do after the Dolls ended?

After the Dolls, me and Syl played. We used to call ourselves the Doll-ettes. We had a great band, played a lot of insane gigs, had a lot of great adventures. But it wasn’t a permanent thing. We were just keeping our chops up, and we were writing songs, like Frenchette, stuff like that. I can’t remember exactly how that ended, but I met this guy, Frankie LaRocka, and he kept bugging me to come and hear this band he was working with in Staten Island. So I went over and they were like a ready-made band, playing in the garage. I really liked the way they sounded, so we started booking gigs.

Do you think history remembers the David Johansen band records well?

I think so. I get a lot of compliments about those. That was when I really hit the road. We used to play like 280 nights a year, in a van. I put in several years doing that. We used to drive 300 miles, do a show, then drive 300 miles and sleep for a while, and then 300 more and do the next show, living in a van and crashing in motels as you go along. Constant touring like that is very educational for giving you the stuff that you need to really deliver every night. But it gets to the point where, Oh my God, I’m going to kill myself.

How did Buster Poindexter come about?

In those days, we had the Walkman, and I used to get tapes of a lot of different kinds of music – jump blues and all kinds of things. So I started listening to all that in the van, and there used to be this bar on 15th Street I used to hang out in called Tramps. They would have Joe Turner there for three months, Charles Brown. But on Monday night, just the bar was open and the back was closed. I decided I would do this little cabaret for four Mondays, under the radar, just for fun. So we put out “Buster Poindexter will be here Monday” – like, who the fuck is that? We started doing that, and by the fourth Monday it was such a scene that we started doing weekends.

You’ve called Hot Hot Hot the bane of your existence.

Well, you know, there’s a lot of things I say like that. I had been down in the Caribbean doing Buster and we heard that everywhere for a week, and I thought, “That’s a cool song, let’s play that when we go home.” Then we recorded it and it was a hit. I went to my nephew’s wedding and they made me sing it – it’s excruciating! It hardly describes what the rest of the music is all about, but you put this thing out there and then people make it what they want it to be for them, and you can’t expect anything else.

“The less you try to accomplish, the better it is. The more loose, the more musical, the more fun.”

Can you believe that, 30 years later, Buster is still in your life?

Buster is an opportunity for me to sing songs that I didn’t write. And I go through phases with music where I get to a point where if I ever hear, like, another blues song, it’ll be too soon. So I went on this whole Latin thing and did the Buster’s Spanish Rocket Ship record [1997], which was really a hoot. Then when that was over, I started listening to Lightnin’ Hopkins again, listening to these songs I thought I knew, and I was hearing them as like a different person. Music has that transcendent thing – you think you’re hearing it, but then go away and be somebody else and come back and you’re going to hear all this other stuff in there that you never noticed before. Soon after, they did some kind of anniversary programme at the Bottom Line [in Greenwich Village] where they had artists come in and do shows that were different to what they had been doing, so that’s how we started doing [Johansen’s folk-blues project] the Harry Smiths. We made a couple of records and played all over the place and got into another world of people, playing Newport Folk Festival and places I hadn’t really been to before, which was kind of a cool thing. And I was simultaneously singing with [Howlin’ Wolf’s guitarist] Hubert Sumlin. We became really good friends and started doing a lot of ‘Howlin’ For Hubert’ gigs, which was a whole other world, too.

And then in the middle of all this comes the 21st century New York Dolls reunion.

We didn’t know that was going to happen. Morrissey wanted us to do this gig, and we went over to London, played at the Royal Festival Hall and stayed in a really nice hotel. Arthur was there and it was beautiful. Then Arthur got sick and passed away, but we were getting offers to play festivals around Europe and we thought, “We sound great, let’s just do it.” We just kept accepting dates and then it was a year later and we were like, “I guess this is what we’re doing,” so we made a record. It was so great for me philosophically, because I was able to experience it and see where it took us, as opposed to trying to fit a square peg in a round hole and getting frustrated because it wasn’t working. It was kind of a zen thing. It was really good – we went around the world three times, did three albums. We toured for eight years, which is more than most bands are together.

Did you know that the interest, the hunger for the band was out there?

It hadn’t occurred to me. I don’t know that it was hunger; it was curiosity. But also we’re a pretty good rock’n’roll band, so people would come back and see us again. It wasn’t Madame Tussaud’s, it was a pretty good band.

Does it feel like a resolution, a kind of justice, that after all these years of people talking about the commercial disappointment of the Dolls, now you’re playing big stages, selling out all these rooms?

This is the whole thing, this is the frigging psychosis of the times. You read about the Dolls and it’s, “Oh, they failed to achieve commercial success” – whatever, to the majority of the people, is success. Whereas when we were in the Dolls we were certainly not shooting for commercial success; we were in on the ground floor of this revolution that was going on, and it was the opposite of commercial. It wasn’t supposed to be commercial. But people can’t wrap their head around that; that’s an idea that’s alien to most people. People are so into getting and spending that I don’t even know if, when they’re on their deathbed, they realise that they’ve been shovelling shit for the man for the last 70 years. But there’s a lot more to life than that.

What do you think is most misunderstood about the Dolls?

Oh, everything. New York Dolls was a very hip kind of collective for its time. We were very socially involved in the whole scene in the East Village – I guess you would call it the arts scene but that’s such a corporate name now. At the time it was just people making stuff and doing stuff for political reasons. We inspired a lot of people. Not just musically, but to do and to get involved and have fun with it. If you think about what it is to be an artist, that’s what you’re supposed to do.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 256.

PILLS FOR THRILLS

Lois Wilson sifts three pearls from DJ’s box of delights.

The glam/punk bible!

New York Dolls

(Mercury, 1973)

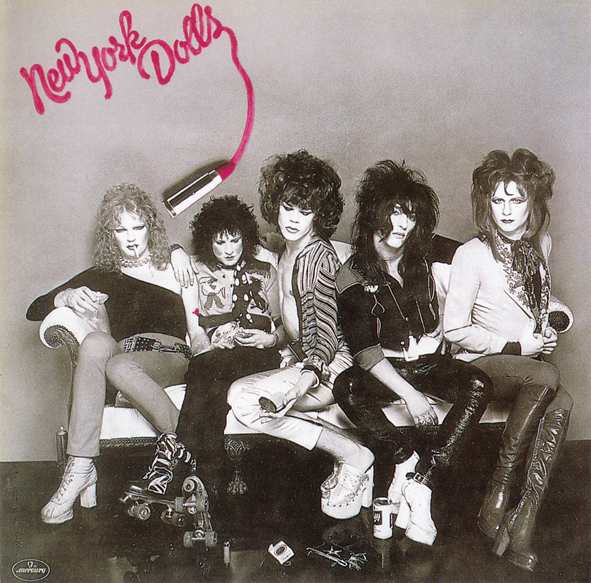

The Tough But Tender One:

David Johansen

(Blue Sky, 1978)

The first of four albums for Columbia imprint Blue Sky, Johansen’s solo debut places the Dolls’ street aesthetic in a hard-rock setting, exemplified best on the Johansen-Sylvain co-write single, Funky But Chic. “Mama says I look fruity, but in jeans I feel rotten,” sings Johansen, peacock-strutting over a Stonesy disco groove as Labelle’s Sarah Dash and Nona Hendryx coo behind him.

The Dolls Come Alive!

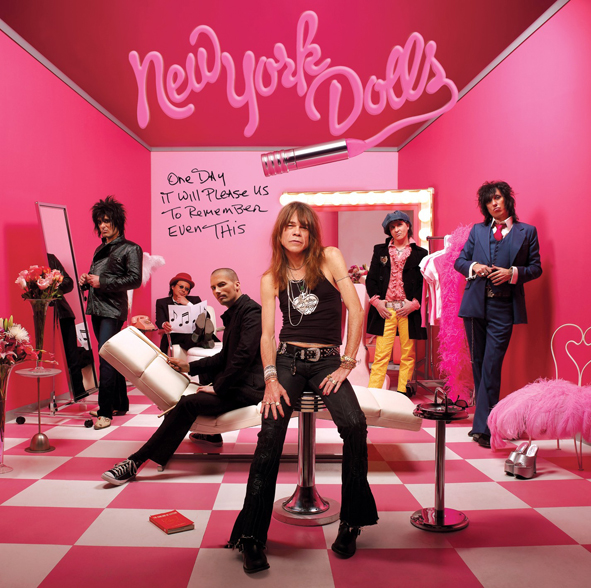

One Day It Will Please Us To Remember Even This

(Roadrunner, 2006)

Belated third album by the two living dolls – Johansen and Sylvain – it has a heart full of soul and a belly full of mischief. Michael Stipe lends vocals on the countryish Dancing On The Lip Of A Volcano; Iggy Pop crashes Gimme Luv And Turn On The Light; Rainbow Store rewrites The Shangri-Las’ Give Him A Great Big Kiss; glee-frugging Dance Like A Monkey invents the word “polymorphosise”.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 266

Images: Guy Eppel, Getty