Mojo

Presents

The Madness Of King Dub

Was Lee “Scratch” Perry – reggae’s wildest producer, alchemist of sound and “God’s Scientist” – authentically mad? Or was it an act to deflect gangsters and journos? A vibration from a higher plane of existence? And would Perry deign to explain himself to MOJO? “Serious joke, that’s what it is,” he told Ian Harrison.

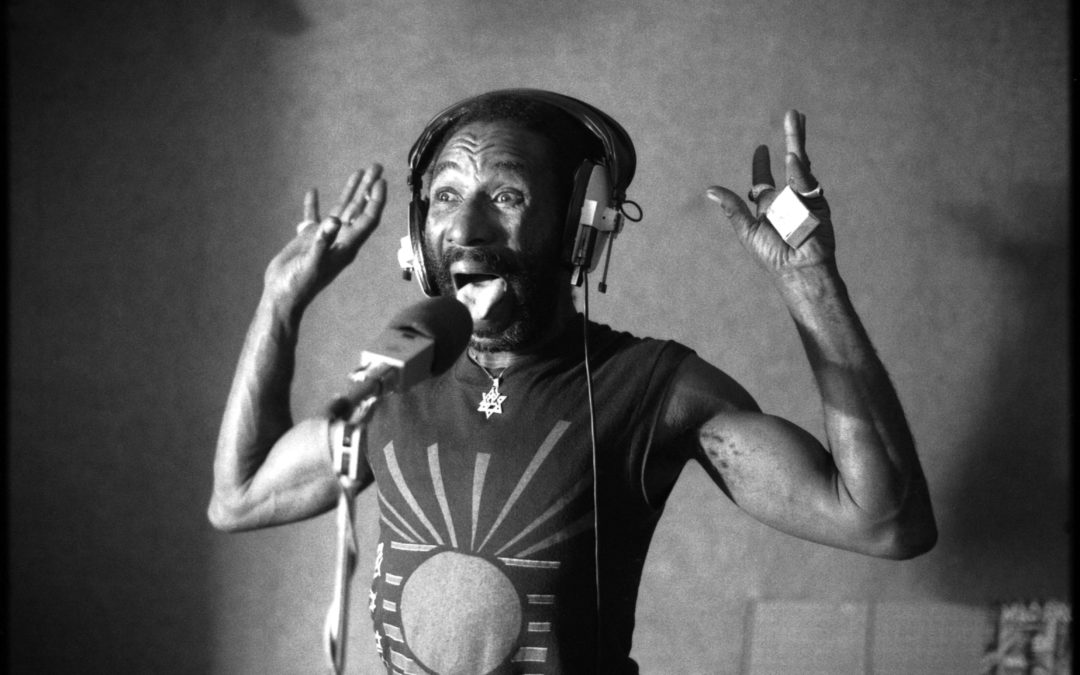

Revolution Dub: Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry in the studio c.1980.

“Are you fuckin’ mad?” reggae legend Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry asks MOJO, coldly displeased at an attempt to communicate. “I’m trying to get ready for a show. Fuckin’ behave yourself.”

It’s 2019 and we’re in a black Toyota Verso, running late and speeding down the darkened motorway from Bristol. This March 14 gig at the Gloucester Guildhall is the opening date of a UK tour taking in such off-piste reggae hotspots as Perranporth, Holmfirth and Kingsbridge’s Pig’s Nose Inn, and the pressure’s getting hot.

The lengthy in-car summit promised by Scratch’s press handlers has not gone to plan, and the near-two-hour first leg of the journey from Heathrow finds him in taciturn mood. Resplendent in a regal ermine robe/ dressing gown, crystal and badge-encrusted baseball cap and dyed crimson beard, the producer, vocaliser and omni-trickster landed late on a flight from Zürich. On arriving at our transport, he occupies the backseat with a large suitcase on wheels which is reputed to hold certain spiritual stones and other special items.

All attempts at conversation flop and wink out of existence. As the car descends the circular ramp from the airport carpark, and the 285 bus to Kingston rolls past, the silence deepens and solidifies.

After an hour of sitting up front, listening to Scratch breathe and tap on his gold iPhone, MOJO asks again if we can speak. “I was dreaming when you just tell me you want to talk to me,” says Scratch, who would turn 83 in six days’ time. “I dream when I am awake, life itself is a dream. I’m writing what I dream, I have them all on computer (holds up phone)… the music always come from dream. The invisible being that talk, you hear words from nowhere. The Father God, him touch you sometime and say, Look at that, in order that you can make a story, and become a teacher, that people can learn and clear their mind and think about a future.”

The legend of Perry the riddler and madman has been established for 40 years now – being told you’re cracked by him is a badge of courage MOJO will wear with pride – but his gaze is steady as he bats away enquiries of mere earthly import and gets on explaining his divinely inspired cosmology. Meanwhile, there’s a services stop for the artist to pick up the Daily Mail and the National Enquirer (Scratch-appropriate stories, respectively: ‘Hurrah For The Budget Big Bras’ and ‘12-Year-Old Creates Fusion Reactor At Home’). Yet he’s disinclined to talk for long.

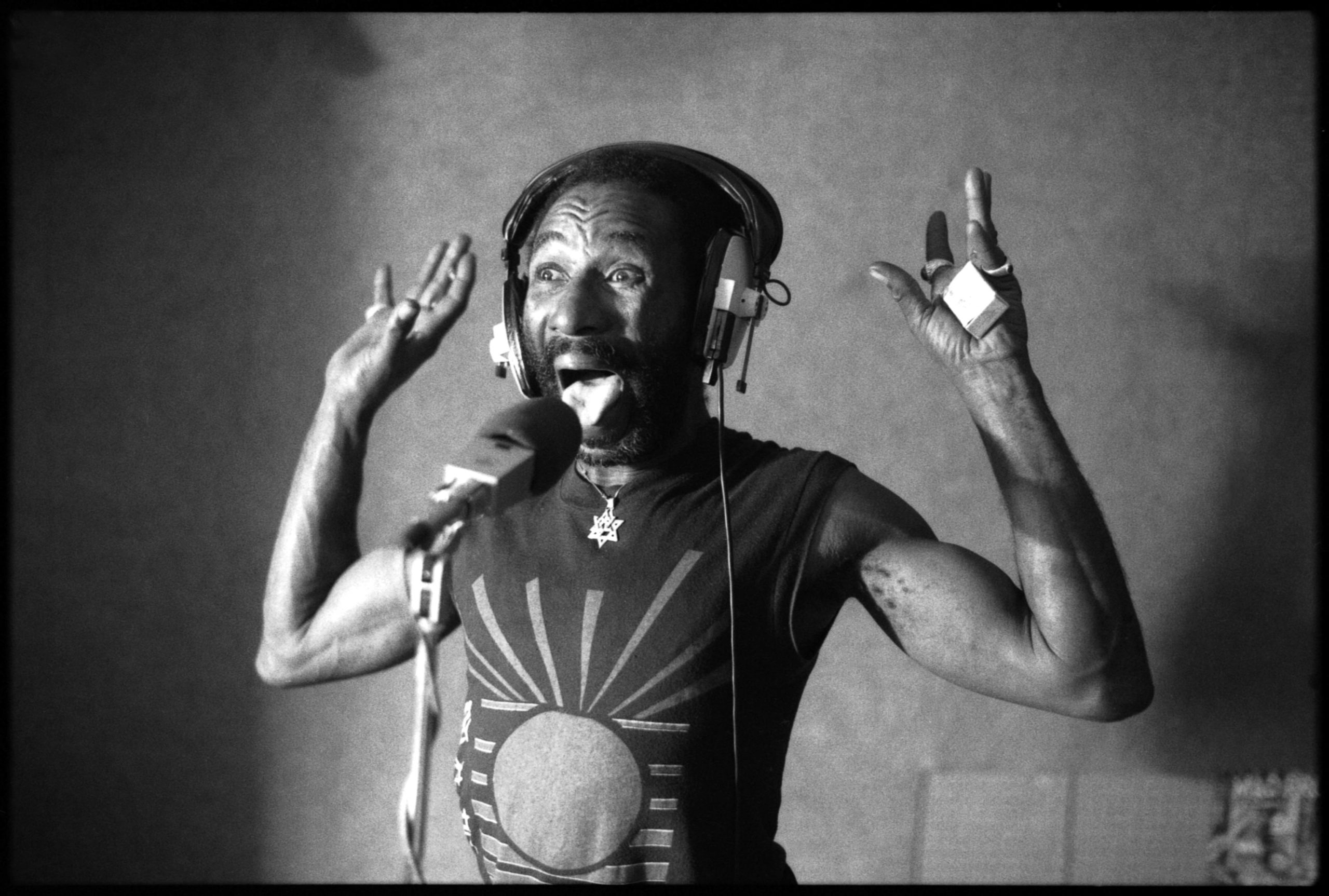

Mystic Warrior: Perry performs at Poppodium De Flux, Netherlands, in 2018.

When our somewhat subdued party finally arrives at Gloucester Guildhall, there’s only minutes to spare before the 9pm showtime and we find Scratch’s band – Strasbourg reggae three-piece Easy Riddim Maker – locked out of the dressing room. Before being guided away from the backstage area, MOJO sees the Mighty Upsetter fist-bump his group in turn, though nervous first night grimaces are seen.

Yet the show is triumphant. ERM are solid and well-versed in Scratch’s oeuvre: bubbling, grooving and extrapolating in all the right places, with sound-expanding dubular extras delivered via laptop. We get spirited versions of such Perry-produced prime cuts as Police & Thieves, Ketch Vampire, Roast Fish & Cornbread and War Ina Babylon, as Scratch speak-sings reordered lyrics, stands on one leg and touches his toes, manically grins at the sell-out crowd and accepts shiny gifts from fans, including a watch, a mirror and a spoon, which he pretends to eat with while crying like a baby. An adapted version of Max Romeo’s Chase The Devil is addressed to the former head of Island records: “Send Chris Blackwell down to hell!” The suitcase on wheels stays close to him throughout.

“I dub you because I love you!” he tells the audience in farewell. But there are limits to Perry’s emanations of affection, and an attempt to reboot MOJO’s interview after the show is thwarted when he disappears quickly into the West Country night.

“Him just come on brave and say what him want to say and no care who vexed,” says Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, who produced the Wailers’ Tosh-led 400 Years and Downpressor. “Peter didn’t see himself as an artist to sing harmony; he have a star quality, but it did need somebody else to put out Peter’s message, because if I promote the two of them, Peter and Bob, it would be a big jealousy.”

Disgruntled with the increasing spotlight on Marley and fatigued by the band’s touring schedule, Tosh left the Wailers in 1973, shortly after Livingston. Seeking to extricate himself from the group’s Island Records contract, Tosh is said to have threatened label staffer Benjamin Foot (also the son of former governor, Sir Hugh) with a machete.

“I was a huge fan of Peter and respected him a lot, because he was truly brave — brave and crazy.” says Island boss Chris Blackwell. “But he never cared for me too much and called me Chris Whiteworst, and as soon as Don Taylor came in, he was managing Bob Marley and didn’t want Peter and Bunny around.”

“God send me to destroy the Queen, the Duke, the Presidents, the governments, the police.”

Lee “Scratch” Perry

One place where Lee Perry reveals himself more willingly is on his new album Rainford. Produced by On-U Sound mainman Adrian Sherwood, it presents vivid, electro-acoustic dubs peppered with biographical detail, past achievements, warnings, parables, philosophies and other ciphers for Scratch’s five decades-plus life in music. Recorded from 2017 in Negril in Jamaica and Ramsgate, it’s also the most consistent Perry transmission since his ’70s golden period.

“My right name is Rain – Rain-ford Hugh Perry,” Scratch reasons, in a much friendlier chat a few days after our M4 impasse. “I think this album could be a good education for the people. It’s about telling a story about my past life, and my present life, and I think it has a good vibration, a real good peaceful vibration.”

It culminates in closing track The Autobiography Of The Upsetter. A rolling, morphing rumination that echoes classic Perry productions, this uncommonly lucid sketch of his life details his birth in poor, rural Hanover Parish, Jamaica on March 20, 1936 and his parents Henry Perry (“a freemason”) and Ina Davis, “an Ettu queen” whose spirit- and ancestor-communing dances can be traced back to the African Yoruba presence on the island. Mum and dad, the song tells, “share a drink together, say them gonna make a godly being.”

“I used that Johnny Cash/Rick Rubin album, *American Recordings, a very intimate record, as the model for it,” says Sherwood. “A lot of the records Lee’s made have him as this jovial, funny ha-ha figure, and he has got that eccentric side and childlike humour, but there’s also the very serious side that’s produced all these great records. I thought, Tell a story and give a bit of yourself, which is something he tends not to do all the time. He’s at a certain age now. Let’s see the real Lee.”

Since he arrived in Kingston in 1961, there have been several Lee Perrys, all playing different roles. Famed early on as an exceptional dancer, he was first turned onto music by the sounds of American R&B. “Fats Domino was my favourite artist, my number one,” Scratch recalls. “Otis Redding was my favourite singer – ‘I’ve got dreams to remember,’ ha ha! It was the soul of the music, you are getting the spirit… it is fire, a flame of fire, and you are caught up in it.”

Working as factotum to Studio One production heavyweight Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd, he hawked his songs in the cutthroat music business centred around downtown Kingston’s Orange Street. His mid-’60s output as a singer included ebullient ska smut-fests including Doctor Dick and Roast Duck, though even here there was an emerging idiosyncrasy and particular intensity. After leaving Coxsone, frustrated at his musical ideas going unrecognised, Scratch set up as a player in his own right. Attempts to move forward with producer Joe Gibbs having floundered, the first Lee Perry hit would be 1968’s People Funny Boy, an attack on Gibbs’ lack of generosity that featured the sound of a crying, hungry baby and an early appearance of the beat that would become known worldwide as reggae.

“They wasn’t nice people who wanted to teach people,” reflects Scratch on those days of producer rivalry. “Coxsone wasn’t such a nice guy. He was all about stupid, he want to rule other people, to be a big bully and a top man. They love to fight and beat up people.”

Did Scratch ever fight?

“Not really. Me is here to heal people, not to destroy them… unless they deserve to be destroyed. Because even God destroy people, if they are ungrateful and unrighteous.”

“Ronnie Wood was a really good friend of mine and I introduced Ronnie and Keith to Peter,” claims Al Anderson. “They fell in love with the guy and wanted to help.”

Jagger and Richards had been fans of Jamaican music since the early 1960s. More recently, The Stones had recorded Goat’s Head Soup in Jamaica in 1971 and Richards was spending more and more time there, having purchased a home in Ocho Rios. Signing Tosh made sense, but Ahmet Ertegun, head of Rolling Stones Records’ parent label, Atlantic, was hesitant; meanwhile, Virgin also had their eye on Tosh.

“I see a lot of misrepresentation on how we ended up with The Stones,” suggests longtime Tosh manager Herbie Miller. “Arma Andon was a Tosh fan at Columbia who hooked us up. We began negotiating with Earl McGrath [President of Rolling Stones Records], having sit-down conversations in New York, but Richard Branson wanted to sign Peter too. One day we drove over to Peter’s home on the outskirts of Spanish Town; Branson is barefoot with a leather bag, khaki shorts and a short-sleeved jacket like he was on safari. We sit on the ledge of Peter’s veranda and Branson said, ‘The only thing The Stones can offer you that I can’t is a tour with The Rolling Stones.’ And the rest is history: in April, Mick and Keith came to Jamaica on our invitation to see Peter perform, as they had not seen him previously: ‘Peter will be doing the Peace Concert, so why not come down?’”

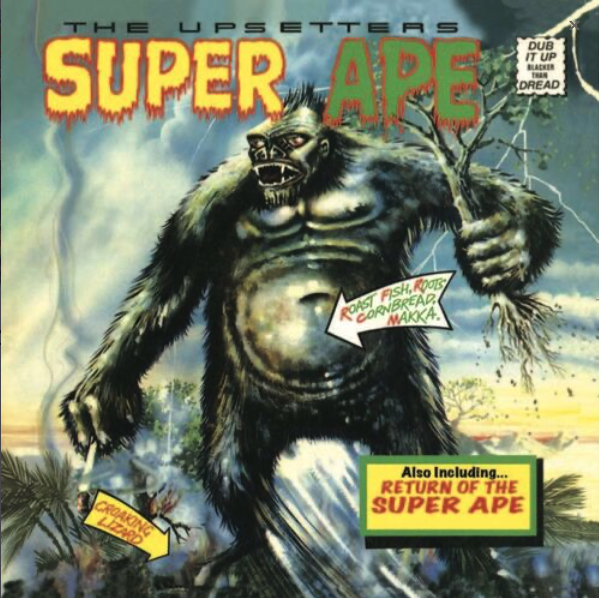

The Upsetter’s Super Ape, 1976.

This steely instinct informed the next, extraordinary decade of Perry’s production career. The Hippy Boys, soon renamed The Upsetters, were the ace house band who would build on the success of 1968’s gleeful Return Of Django – actually recorded by Gladdy’s All-Stars, and a Number 5 UK hit in November 1969 – playing on a series of albums with loose western themes which presented cockeyed, chugging organ instrumentals and vocal R&B covers. The Jamaican public had started taking notice.

“Scratch was like the new generation,” says Dennis Alcapone, DJ and eyewitness. “Before him the top producers monopolised the scene, people like Sir Coxsone, Duke Reid, Prince Buster, all those people. He came with a different genre, actually – Scratch’s type of riddims, they were different from the norm, and that sound started to dominate.”

In 1970, a fellow unreimbursed Coxsone refugee called Bob Marley called at Scratch’s Charles Street premises. Their collaboration would result in The Wailers’ seismic first two LPs, as well as the anthemic, Coxsone-bashing Small Axe. Yet history would repeat itself, after a fashion, when Marley split with Perry, his international ambitions leading him to Chris Blackwell’s Island label in 1972. Scratch was so incensed – Marley added insult to injury by taking The Upsetters with him to be the full-time Wailers band – that he would, Dennis Alcapone says, throw darts at pictures of Jamaica’s future superstar. Yet the two reggae titans would work together again on occasion, as on 1977’s JA-UK hat-tip Punky Reggae Party.

“My job was to tell him what the spirit want me to tell him,” says Scratch today of Marley. “It was very great doing that, for a young man, to show him the way to have a family and an education and to become a king. I think he learned a lot from me, and he’s somebody that I love very much, to the heart (touches chest).”

“He worked fast, and he danced while he mixed. He had four tracks on the board and eight tracks in his head.”

Max Romeo

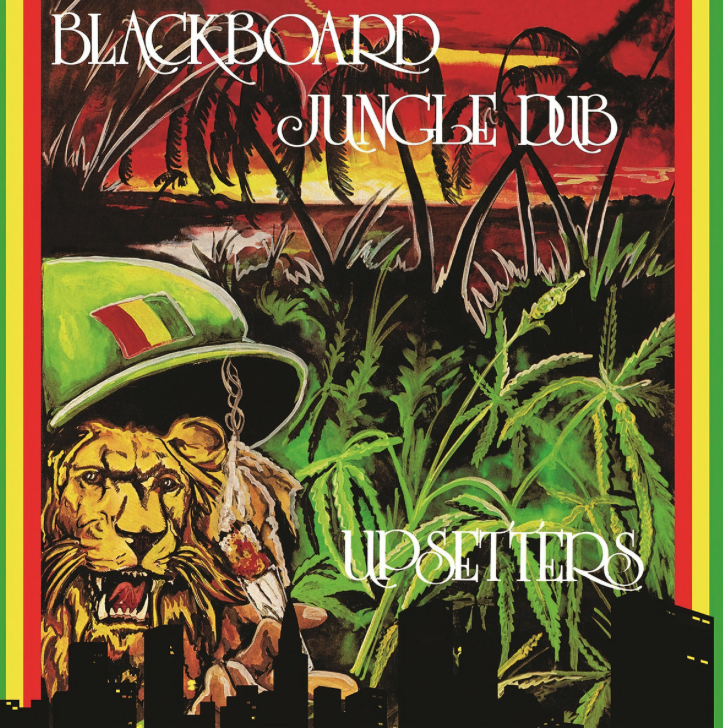

While Marley’s departure must have stung, 1973 saw Perry’s creativity shift into high gear. That year’s Double Seven, where I-Roy, U-Roy and various squiggling analogue synthesizers met in a grooving fug of increasing sonic confusion, was followed before the year’s end by one of Perry’s most satisfying, game-changing shots to the head. Released on an estimated edition of just 300 copies and mixed at King Tubby’s studio using existing Scratch-produced rhythms, Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle played wildly with stereo, foregrounded planet-sized sound effects and transported listeners into phantom zones of drum and bass. “Japanese made equipment and I love to use it,” says Scratch of the inexpensive studio kit he favoured at the time. “Japanese always on my shoulder. That’s why I’m not getting any older…”

Its location revealed to him in a vision, Scratch would build his storied Black Ark studio in the grounds of his home in Kingston’s Washington Gardens neighbourhood. The four-track facility would be fully operational in early 1974.

“The Black Ark was another education,” he says. “It was a museum, a museum study about God’s creation. God make the Ark of The Covenant to control the universe, so me just called it Black Ark, because the Ark is black, and the art is black and the heart is black. It’s all about the shadow of a man. Even if you are white, your shadow’s black. You are two people walking, you are the day and the night… it was a positive vibration there.”

In 1976 and 1977, such spiritually charged reggae classics as Max Romeo’s War Ina Babylon, Junior Murvin’s Police & Thieves, The Heptones’ Party Time, Scratch’s own Super Ape and The Congos’ Heart Of The Congos would be recorded there (all but the latter would be licensed by Chris Blackwell’s Island for European release). “They were the best of days,” remembers Max Romeo. “The Black Ark was a very small space, very clean, the equipment was very miniature. Scratch didn’t like to rent it out a lot unless it was to people that he knows. He was what I’d call a professional, and a musical genius – he’d keep bouncing from track to track [ie. mixing four tracks down to one to make room for more overdubs]. He worked fast, and he danced while he mixed. One of his phrases was, he had four tracks on the board and eight tracks in his head. And he’s very inspirational, very comic. He’d make you laugh – in those days, there was never a sad moment around Scratch, man.”

Romeo also attests to the producer’s ability to pick a hit. Initially, the singer disliked Chase The Devil, the screwy 1976 roots exorcism that would prove to be his most celebrated recording. “Scratch said, You’ve got to be kidding, this is what you call original, it’s the best track on the album. And it’s true. He’s got vision.”

1973’s Blackboard Jungle Dub

“God burned it down with fire because God want me to come to the world,”

Lee “Scratch” Perry

The vision was spreading. In 1977 Scratch produced The Clash’s Complete Control, and Paul McCartney sent for backing tracks for Linda to re-voice: soon after, Robert Palmer came to record at the Black Ark. In Cologne, krautrock superpower Can were also listening. “This music was really new, but also what was so fascinating was the way he used the studio as an instrument,” says Can keyboardist Irmin Schmidt. “Playing the mixing console like it was a keyboard, moving the faders with the rhythm… that means you pick up the atmosphere and the acoustics in the room and explore them with whatever you have, technically. If Can had been produced by Lee Perry? That would have been wonderful.”

Yet for the Black Ark, destruction was approaching. After Island declined to release 1978 Perry albums Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread and Return Of The Super Ape, output slowed and inspiration faltered. YouTube footage of a lively mid-’70s Junior Murvin session compares unhappily with its murky and debris-strewn 1982 incarnation. Then in mid-1983, the disintegrating studio was consumed by fire.

“God burned it down with fire because God want me to come to the world,” is Scratch’s explanation today. He has previously declared that he burned the Ark himself. “I think he was sick of being hustled, gangster people coming round trying to screw him for money all the time,” is Sherwood’s understanding of why the Ark fell. “That and personal issues, and a combination of spliff and too much rum… he cracked up a bit, and decided to let everyone think he was mad.”

Max Romeo agrees that reports of Scratch’s mental instability have been exaggerated: “He started acting a certain way to get guys away from him. Finally, everybody did scatter. Then everybody starts saying he’s mad, pay no mind. I always say, he’s eccentric to a dimension, but I think it’s all an act, a gimmick. When I see him he always talks to me normally. Scratch is not mad.”

But, with Scratch declaring “divine madness is the greatest power”, calling fire his father and being seen sipping petrol at an ’80s UK studio date, it certainly seemed that he was in the grip of some psychic turmoil in the years that followed. At times of great stress, has he ever lost touch with who he is, MOJO wonders?

“I cannot forget who I am,” says Scratch. “Because the thing that I do, people believe in it. So I have to live with what I do, and make it manifest and come to life. If a rough time come along, I go through the rough time until the time right to be God-time, and when it God-time, nobody can stop it.”

Having moved to London in 1984, since 1989 Scratch has resided in Switzerland with his wife and manager Mireille Campbell. The last 35 years have seen him record 40-odd post-Ark albums with the likes of the Mad Professor, The Orb and Sherwood’s On-U set up. Standouts include the latter’s 1987 Dub Syndicate team-up Time Boom X De Devil Dead and 2008’s The Mighty Upsetter, though almost all have a spark of the old fire about them.

“Scratch still has an incredible creative drive,” says Emch of New York bass merchants Subatomic Sound System, who’ve replicated the Blackboard Jungle and Super Ape albums for collaborative live performances with Perry in recent years. “When we were recording with him, if there was 10 minutes downtime, he’d start drawing or doing something else. He’ll give you directions that have to be interpreted and decoded, but you can’t tell him what to do. ‘Cos his name is Rainford, he’ll say, ‘You can’t control the rain, fuck you!’ And he’ll destroy things as quickly as he’ll create them. You can talk about how he was the first producer to be considered a musician, or his influence on hip hop – Kanye West is a cheap knock-off of Lee Perry, in a way – or how he’s the unsung godfather of exactly what’s going on in music today, but actually, he’s transcended his own genres. He has no fear, basically.”

“The Holy Spirit want me to never sell my soul to the devil for money, nothing like that. I am working for God.”

Lee “Scratch” Perry”

In 2019, Lee “Scratch” Perry knows exactly what he’s doing, he says. “God send me to destroy the Queen, the Duke, the Presidents, the governments, the police and the soldiers. I am God lightning and God’s scientist, I do God magic and I do God miracles…”

In 2012 he was also awarded the Jamaican Order Of Distinction. “Uh-huh,” he says. “Everything is alright in Jamaica.” There is method in his madness, clearly. “Serious joke, that’s what it is,” he says. “I’m glad for serious jokes. But I don’t support the Joker. Superman, Batman and Robin and Spiderman are my favourites. I love comic, most of my music are comic. Superman X-Ray vision, he see you when you go to bed, he sees you’re asleep, when you dream a dream, that’s super-vision, I have it. This is where the music come from, from dream, from super-hero, from man named Stan Lee. I am Stan Lee’s number one fan. He is still with us, all the time, not for a moment, but forever. Stan Lee and Lee Scratch Perry, forever!”

Intoxicated by his singular company, it’s not such a stretch to equate Scratch’s eternal battle with evil with the archetypes of the Marvel universe. Eighty-three years forever young, off the booze and ganja and eating healthily, Rainford Hugh Perry is still throwing words of power at his enemies.

“I’m not running down money and riches or silver and gold,” he says, our audience approaching an end. ”The Holy Spirit want me to never sell my soul to the devil for money, nothing like that. I am working for God. The people who don’t work for god are devil-people…”

And who is a good person, Scratch?

“I am a good man, I am sure of that.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 307

Images: Getty