Mojo

Presents

Blood + Fire

In 1976, reggae was peaking – creatively aflame, and with its biggest star poised for global stardom, fuelled by the positive protest of Rastaman Vibration. But with a General Election due and domestic bloodshed rampant, Bob Marley was drawn into Jamaica’s bitter ‘politricks’ and menaced by the gangsters who enforced them. The year would end in one of the most dramatic and mysterious events in music history. “We were trying to bring peace and unity in the country,” discovers David Katz, “and they tried to kill us.”

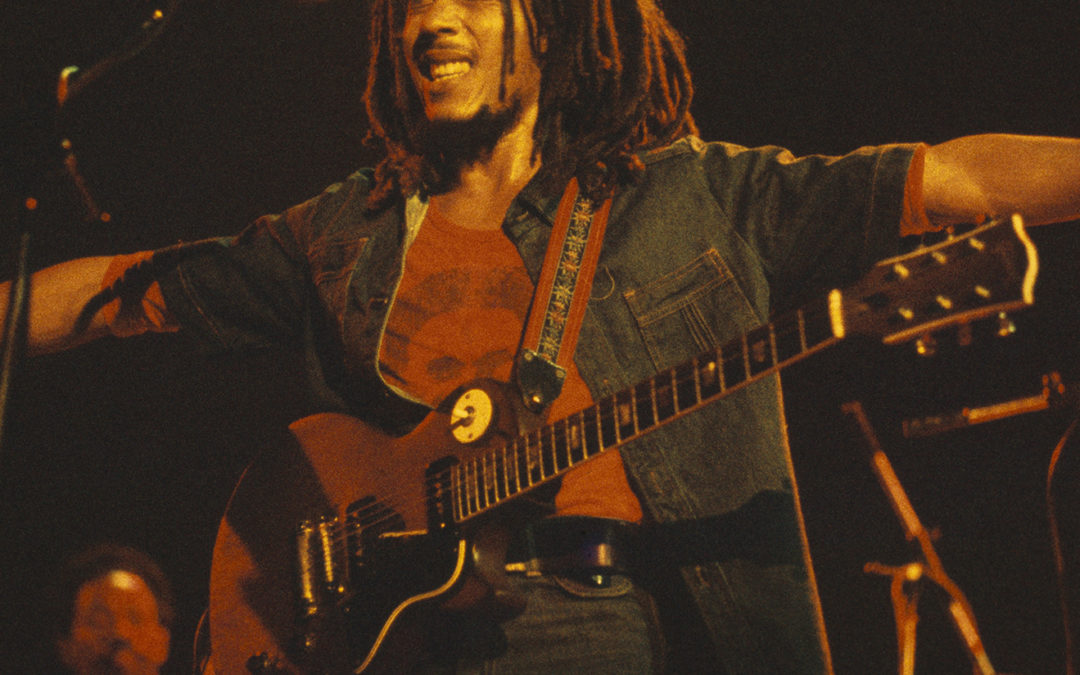

Natty Dread: Bob Marley performs live on stage with the Wailers in Voorburg, Holland in 1976

It’s the evening of 3 December 1976, and Bob Marley and The Wailers are rehearsing at their 56 Hope Road headquarters in uptown Kingston. The Rastaman Vibration album and tour has won them a new wave of fans across the world, and the group is preparing to take it to their compatriots at the Smile Jamaica concert, a free event to be held at Heroes Park in two days’ time. But the gig has just become problematized, since Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley announced a snap election to be held just ten days after the show. With Manley’s government helping to stage Smile Jamaica, the event and the election would be linked in people’s minds, suggesting Marley’s tacit support for the reigning People’s National Party (PNP), which greatly angers supporters of the right-wing opposition, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP).

After rehearsing for about 30 minutes, Marley takes a break and wanders to the adjacent kitchen at the rear of the property, flanked by his manager, Don Taylor, and guitarist Donald Kinsey; Rita Marley exits the front door as the rest of the band, and an entourage of Twelve Tribes of Israel members, remain in the rehearsal room. Then, as Marley reaches for a grapefruit and begins to peel it, unwelcome guests make their presence known with terrifying swiftness.

“I think we were playing I Shot The Sheriff and then I started hearing gunshots,” remembers keyboardist Tyrone Downie. “I saw a hand come round the door, just firing in the room, and instinctively, we all hit the ground; everybody swam to the bathroom, and when I got in there, Carly [drummer Carlton Barrett] was already in the bathtub. Then we saw Bob come in, bleeding, and I think we were all waiting to just be shot, cause there was no way out. Like, this is it: we’re all gonna die in this fucking bathroom.”

“I was playing percussion with [Wailers’ percussionist] Seeco [Patterson],” adds Twelve Tribes member Sangie Davis. “When the shots started, I ran into the bathroom, and someone was inside the bath. Me and Bob end up in the corner and somebody put a gun through the window, but no shots didn’t fire, because the bathroom was very dark. Then a lull passed, and nobody wanted to come out of the house. As a matter of fact, Rita was driving out when the people were coming in, and she got grazed.”

“Rita distracted them, and I think she saved our lives,” says Downie definitively. “We heard a car driving out, and they started shooting at the car; if no one was driving out, probably they would have kept coming in and just finish us off.”

Bob went to the hospital with a bullet lodged in his arm and Rita with one in her head; Don Taylor was airlifted to Miami for emergency surgery and miraculously survived, as did Twelve Tribes member Louis Griffiths, who’d been shot in the back. 1976, which had delivered so many landmarks for Bob Marley – including a classic album and the prospect of a real breakthrough in the US – as well as an extraordinary bounty of Jamaican music in toto, was ending in horror and confusion. Who wanted Jamaica’s cultural figurehead dead, and why?

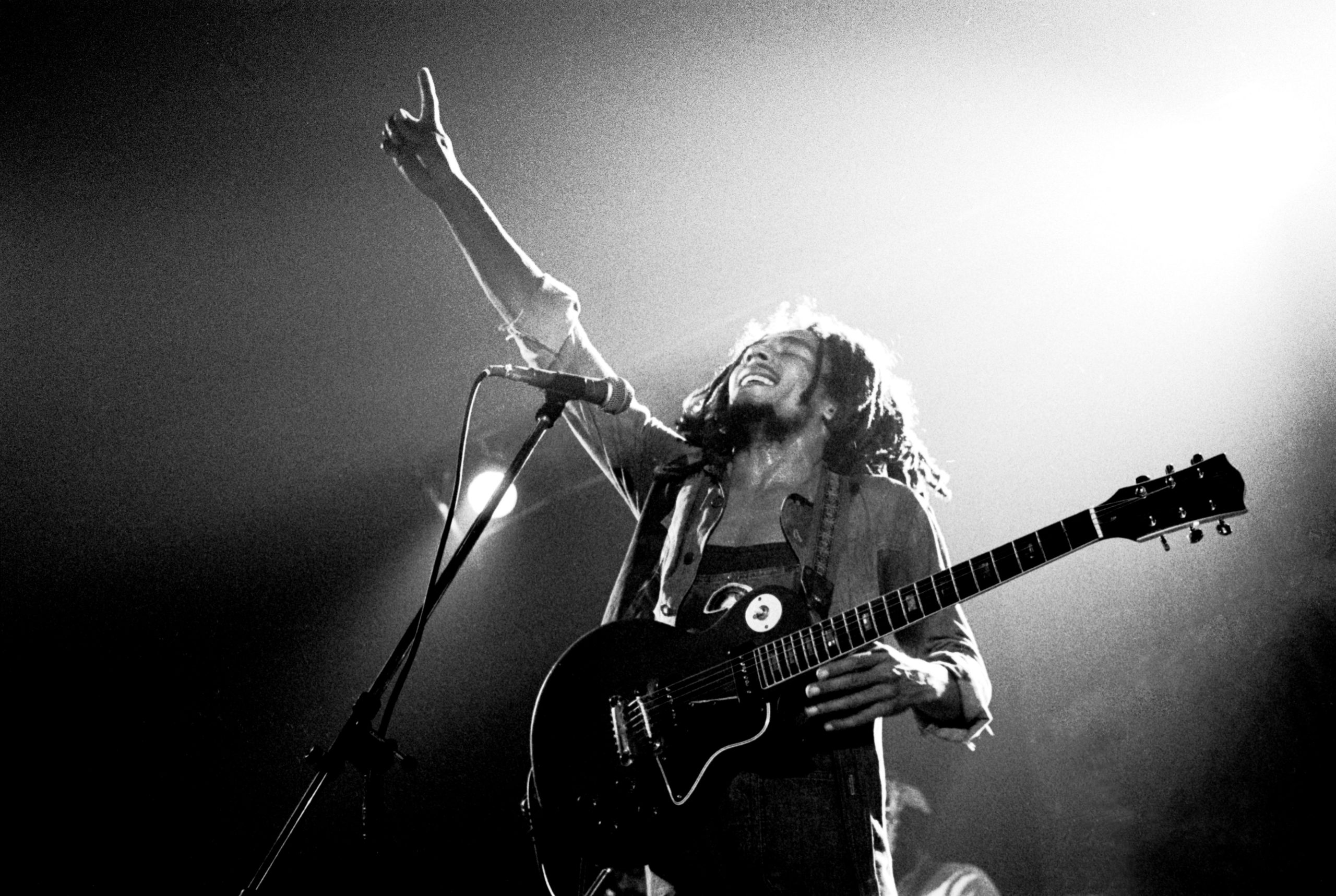

Roots, Rock, Reggae: Marley mania hits the UK, Hammersmith Odeon, London, June 1976.

IN JAMAICA, POLITICS, criminality and music culture had been intertwined for as long as anyone could remember. The island’s two-party system had been born in the bitter labour disputes of the 1930s, the PNP built on Fabian socialism and JLP championing the free market. With party leaders drawing tangible support from a criminal underclass, who ultimately bossed the electoral districts of Kingston, partisan violence was already a problem in the mid-’40s, and the bourgeoning street gangs escalated their battles in the run-up to Jamaica achieving its independence from Britain in 1962.

It was a reality that musicians and record business entrepreneurs were obliged to work within and reflect. Joe Higgs, who tutored The Wailers in Trench Town, described the politically-aligned street battles on a 1961 single called Gun Talk, recorded with his singing partner, Roy Wilson. The JLP’s rising star, Edward Seaga, who had opened the West Indies Records Limited recording studio before devoting himself to politics full time, held his constituency meetings in one of west Kingston’s most prominent dancehalls, and ska legend Cecil Bustamente Campbell – aka Prince Buster – was even named for JLP founder Alexander Bustamante. Such links would become more explicit in the mid-’60s, when harmony groups like The Tartans and The Slickers had gang members pass through their ranks.

The elections of 1967 and 1972 saw increasing levels of violence, and alarm bells began ringing farther afield when Michael Manley declared an era of Democratic Socialism in November 1974, directing the nation further left through closer ties with Cuba. Opposition leader Edward Seaga appealed to the Ford administration in Washington, while political violence spun so out of control that Manley opened the Gun Court, a punitive detention centre for firearms offences whose trials took place without a jury, indefinite detention with hard labour the only sentence. Henry Kissinger would soon cancel loans to Jamaica after Manley refused to denounce Cuba’s military intervention in Angola.

At the same time, Marley’s rising overseas status was helping galvanise the Rastafari movement in Jamaica. The Rastafari had emerged in the 1930s, following the coronation of Haile Selassie as Emperor of Ethiopia, after various Kingston preachers began proclaiming that Selassie was God and that the rightful place for black Jamaicans was Africa. The island’s long colonial phase had bequeathed it a distinct racial hierarchy, where anything seen as too African was deemed ‘backward’, so Rasta adherents faced open hostility from the authorities, with instances of police brutality all too common. As a rejection of mainstream Jamaican society, the Rastafari movement naturally proclaimed itself to be non-partisan, since the only government it recognised was Selassie’s divine one. Yet, the Rastafari could not always remain impervious to the capital’s heavily demarcated, conflict-ridden boundaries, with rival politically-aligned communities sitting cheek-by-jowl with one another. The divisive landscape affected everyday life in Kingston, regardless of one’s spiritual affiliation.

“We saw Bob come in, bleeding, and I think we were all waiting to just be shot. Like, this is it: we’re all gonna die in this bathroom.”

Tyrone Downie

YET, WHEN THE Wailers returned to Jamaica in July 1975 at the end of their Natty Dread tour, the island was relatively peaceful, which was just as well, since the exhausted group members needed a break. The defection of Al Anderson to ex-Wailer Peter Tosh’s band just before Tosh signed to the Rolling Stones’ Columbia label also meant that Marley was seeking a new guitarist.

“Peter had the most amazing group with Robbie [Shakespeare, bass] and Sly [Dunbar, drums], it was more of a power-rock trio,” says Anderson. “I wanted to be a part of that because The Wailers had just broken the sound barrier with money, and here comes Don Taylor, the Dapper-Dan manager, and these were the guys that were stealing the crumbs from the band, taking everything that wasn’t bolted down financially. When we did a Bob Marley album, it was like three or four months straight, in the studio, without even taking a shower; I lived at Hope Road and slept on the floor for a year. It wasn’t interesting anymore.”

In pondering a suitable replacement, Marley turned in the opposite direction: New Jersey-born Anderson was essentially a blues-rock player, but Marley opted for Earl ‘Chinna’ Smith, a mainstay of the Soul Syndicate band whose playing style was distinctly Jamaican. Chinna had recently been playing on a Martha Velez’s Escape From Babylon album for Sire, initiated with producer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. “When Bob come back, him hear Dennis Brown and Johnny Clarke, and Bob is a curious man who want to know who are the artists and the musicians,” says Chinna. “So [Marley’s sometime manager] Skill Cole come check I round Scratch’s studio, when them was doing the Martha Velez album, and Scratch just move the session from there to Harry J with all the musicians that was working.”

The Rastaman Vibration sessions thus began in September 1975 at Harry J, the uptown studio part-owned by Marley’s label boss Chris Blackwell. The core Wailers band were bassist Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett, his drumming brother Carlton, and percussionist Alvin ‘Seeco’ Patterson. Main keyboardist Tyrone Downie shared duties with Bernard ‘Touter’ Harvey, as well as pianist Gladstone Anderson and organist Winston Wright. Later, the I-Three, made up of Bob’s wife Rita, Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt, would be brought in to overdub their vocal harmony, while Perry was present early on, making his customary leftfield suggestions. Sessions were apparently relaxed.

“Bob never really had so much rehearsals as such,” explains Marley confidant and graphic designer Neville Garrick, who had recently moved to 56 Hope Road after a ganja bust. “Bob would come up with his songs by writing them with his acoustic guitar and most of the time, the band really heard the song almost for the first time when they went into the studio. Bob used to like a live feel – more of an impromptu feel.”

The censorious Crazy Baldhead, which features subtle blues licks from Al Anderson, was either left over from an earlier session or was one of the first to be crafted that September. The song speaks to the aeons of social injustice that had cemented Jamaica’s social strata, with the black majority at the bottom, and the white and light-skinned upper echelons forming the elite. War memorably adapted a speech that Haile Selassie delivered in California in 1968, speaking of the destruction wrought by armed conflict in Africa. Perhaps strongest of all was Rat Race, which decried Jamaica’s status as a pawn in the Cold War atop a chord structure adapted from a Philly Soul hit.

“Rat Race was just an idea that me and Tyrone jam,” explains Chinna. “Actually, it was one of them R&B songs, The Spinners’ Since I’ve Been Gone, and Carly started to feel it, so Scratch say, ‘Record it!’ ’cause him creative like that. Bunny Wailer was there too, and him say, ‘Add on an intro,’ so that’s my chords at the start. Then Bob write a mad, mad tune; him and Rita Marley come up with the lyrics.”

Politics was unavoidable. In fact, politics came looking for him.

“Edward Seaga walked into the studio during that time, ’cause he was a friend of Harry J,” says Neville Garrick. “So I don’t know if that influenced Bob to say, ‘Rasta don’t work for no CIA.’”

“I wasn’t listening to the conversation,” adds DownieDowney, who says that Seaga appeared when they were working on Johnny Was, which depicted an innocent victim of political violence, “but from what I heard, he came to tell Bob not to support the PNP.”

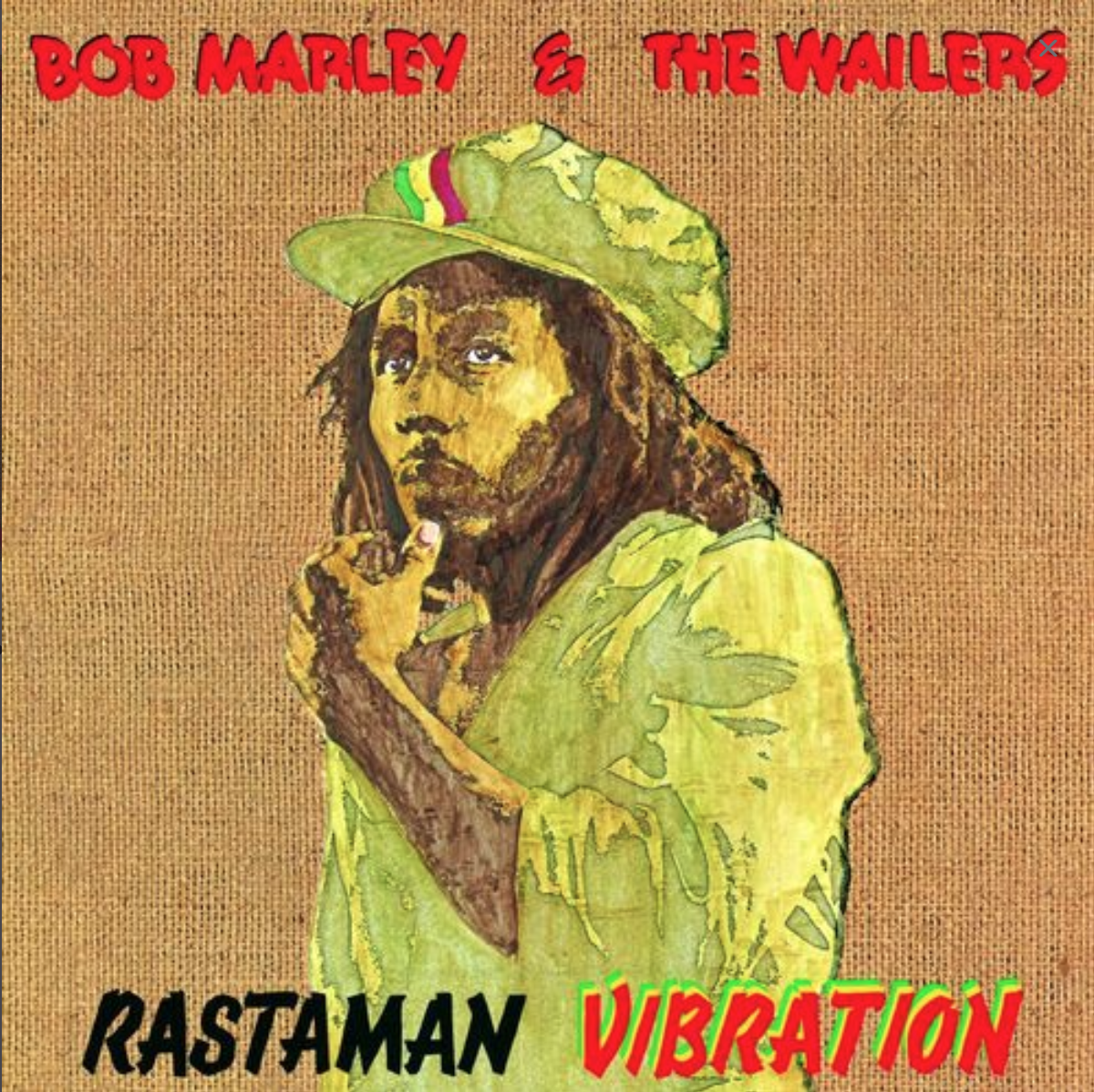

1976’s Rastaman Vibration

IN THE WEEKS that followed, the band laid the bare bones of the rest of the album. Roots, Rock, Reggae and Positive Vibration kept optimism at their core. By contrast, Want More decried greed, and prophesied the triumph of Rastafari over its enemies. The remaining tracks revisited The Wailers’ voluminous back catalogue, Cry To Me, Who The Cap Fit and Night Shift part of Chris Blackwell’s long-term strategy for Marley to earn royalties for material that was not properly registered in the past. Other tracks laid down in September would not surface for some considerable time, including One Love, Three Little Birds, The Heathen and I Know.

Once the basic backing tracks had been completed, the core of The Wailers and Chris Blackwell decamped to Miami to add finishing touches at Criteria Studios, working closely for the first time with Alex Sadkin, a gifted engineer who brought a new sonic clarity. “His real job there was doing the mastering, but I needed somebody to engineer and he was the best engineer I’ve ever worked with,” says Blackwell. “He was a real master at what he did, a perfectionist, and it was really by luck that we used him.”

“If anyone is responsible for the outcome of the sound of Rastaman Vibration, it’s Alex Sadkin,” concurs Tyrone Downie. “He was very precise, had really good ears, and he did a simple mix — not over-producing — so you’re gonna hear the rim-shot, you’re gonna hear the guitar. More a blues mix than a rock mix. Alex could have done a Dylan album or a John Lennon album, easy.”

To further broaden the appeal to international audiences, Marley enlisted Donald Kinsey, the Indiana-born, Chicago-based guitarist formerly of Island Records blues-funk act White Lightnin’. Kinsey had recently been playing with Al Anderson in Peter Tosh’s band but was still surprised to receive a summons from the Tuff Gong. “My dad said, ‘Somebody called for you, sounded like he had a Jamaican accent.’” Kinsey told me last year. “So I called the number and they put me on the phone with Bob, and we talked like we’d known each other for years. He’s just really uplifting, real upbeat, real positive, like, ‘Donald Kinsey, I wonder if you can play some guitar for me?’ It was a new experience for me to hang with those cats, but I found out that we had so much in common, my parents being from the Mississippi Delta, the same types of things that they dealing with in Jamaica, and you can feel that gospel thing in their music.”

The first track they tackled at Criteria was Roots, Rock, Reggae, which gained a new dimension with Kinsey’s blues licks, a ska guitar pattern from Chinna, new percussion parts from Seeco, Chinna and Family Man, and a jaunty sax riff from an unknown local session player. “I told Alex I wanted to get somebody like King Curtis,” says Blackwell, “and later in the day, this small, quiet, white guy turned up, and I said, ‘Well, he don’t look like King Curtis,’ but his playing was fantastic.”

Want More also got the Kinsey blues-rock treatment (cut on the fly, when the guitarist was just doing a trial run), and several tracks were given prominent keyboard overdubs by Downie, with Cry To Me making good use of the then-new Elka Rhapsody, a quaint-looking Italian-built strings emulator. “It had a little weird piano sound, and it had strings, and then you can mix both the piano and strings at the same time,” laughs Downie. “I used the same thing [later]on Three Little Birds.”

Then it was back to 56 Hope Road to prepare for the forthcoming tour. “We just rehearse, play ball, eat food, and probably get some pussy, you know?” says Downie. “That’s what work was about at that time: living together, eating together, playing football, playing music together.”

“Bob was really uplifting, real upbeat: ‘Donald Kinsey, I wonder if you can play some guitar for me?’”

Donald Kinsey

THE EVOLUTION OF Bob Marley & The Wailers into the kind of group international rock audiences could understand and embrace had reached a crucial stage. Meanwhile, beneath the Marley-generated headlines, Jamaican music was entering a hugely creative, varied phase.

Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston had left The Wailers in the wake of the snowbound UK leg of the Burnin’ tour in November 1973 and their divergence, musically and politically, from Marley was exemplified by their solo debut albums, both released in 1976. Bunny’s Blackheart Man opted for insularity, the track Fig Tree steeped in religious allegory and his experience of imprisonment obliquely reflected in Battering Down Sentence. Tosh’s Legalize It took a more in-your-face approach, the title track and Watcha Gonna Do focusing on the victimisation of ganja smokers while Ketchy Shuby recounted his teenage sexual experiences in impenetrable patois. Both contrasted sharply with Marley’s broader themes. On October 4, 1975, the three performed at the National Stadium’s Wonder Dream concert, staged by Stevie Wonder to benefit the Jamaica School for the Blind, but it would be the last time that Marley, Tosh and Livingston would share the same stage.

As 1975 became 1976, reggae was an increasingly broad church. Harmony trios The Mighty Diamonds, The Gladiators and The Heptones joined Burning Spear in widening their audiences through international deals with Island and Virgin. The improvised microphone chatter of sound system deejays such as Ewart “U -Roy” Beckford, Roy “I -Roy” Reid, and Lester Bullock, aka “Dillinger”, was becoming an album genre in its own right, as was dub – originally relegated to the B-sides of singles. Lee Perry’s Super Ape, Augustus Pablo’s King Tubby Meets The Rockers Uptown, Yabby You’s Prophesy Of Dub, The Revolutionaries’ Vital Dub and Tappa Zukie’s Tappa Zukie In Dub were just four of 1976’s outstanding dub LPs.

Neither were Jamaican artists short of subject matter that year. The government declared a State of Emergency in June, with a curfew in effect, and prominent opposition leaders were detained under the pretext that they were trying to overthrow the government. Fires raged downtown in targeted arson attacks. As cannabis growers increased their clandestine exports, there was rapidly declining official trade and a grave shortage of foreign exchange, while unemployment rocketed, leading the island’s business community to increase its steady exodus to Miami — a destination gunmen on both sides of the political divide were also eyeing, pending the result of an election whose date had not yet been set.

Easy Skanking: The Wailers take an Amsterdam cruise, 1976.

ONE JAMAICAN EXPORT, at least, was thriving. With Rastaman Vibration finished and Neville Garrick’s burlap cover art approved, Bob Marley & The Wailers went straight on tour, kicking off at the historic Tower Theater in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania on April 23, and reaching 18 North American cities over the course of five weeks. The dual-guitar format gave an added textural dimension, with Kinsey’s fiery rock lead lines offset by Chinna’s understated reggae licks. The two nights at New York’s Beacon Theatre drew rave reviews (thanks in part to a well-executed PR campaign by New York-based Liverpudlian Charlie Comer), and when the band rolled into Chicago on May 11, Kinsey discovered they were indeed “bubblin’ on the Top 100”, as Marley had predicted in his lyric to Roots, Rock, Reggae.

At the Roxy in Los Angeles on May 26 the stars came out to anoint them. “I remember liking that show because it was very intimate,” says Downie. “Also, it had star-studded guests: Herbie Hancock, Joni Mitchell, Billy Preston, Buddy Miles. I think Jerry Garcia was there too. Who wasn’t there?”

“It was kind of remarkable,” adds Neville Garrick, “because he had people like Ringo Starr and George from the Beatles, and Doctor Hook, all kinds of mega-stars. I think that’s when they said Bob Marley had arrived.”

A press campaign aimed at introducing Marley to the US college audience had paid off. Rastaman Vibration reached Number 8 on the Billboard charts – the highest US chart position any Wailers album would achieve during Marley’s lifetime. It charted in Britain as well, just as The Wailers travelled to mainland Europe for the very first time, starting that leg before a massive crowd at the Sunrise Festival in Offenburg on a shared bill with Wishbone Ash, Stephen Stills, The Kinks, War and Van Der Graaf Generator. “They had a curfew and they actually turned off the sound before we finished,” says Neville Garrick. “That’s the only time I can remember the plug being pulled, and the audience rioted.”

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

“The LA show had star-studded guests: Herbie Hancock, Joni Mitchell. I think Jerry Garcia was there too. Who wasn’t there?”

Tyrone Downie

They went on to three more German cities, followed by dates in Stockholm, Amsterdam and Paris. Then, in Britain, there were four nights at the Hammersmith Odeon, where the band met Eric Clapton, followed by dates in Wales, the Midlands, Leeds, Exeter and Manchester.

“Cardiff was a mad show, because the rain ah fall and Bob just played inna the rain,” says Chinna. “We were afraid he was going to be electrocuted.”

“Leaving Hammersmith, there were people climbing all over the bus,” adds Downie. “It was dangerous, and I really felt like, ‘Damn, we’re rock stars!’”

“My memories of that tour was that everything was just fresh and all the energy was there, because here is a man who is determined to take his message to the world, and he would do it, any form, any way, as long as it’s going over positively,” says I-Three stalwart Marcia Griffiths. “Let me tell you, nothing came before his music; Bob’s music was his life, and he was overwhelmed.”

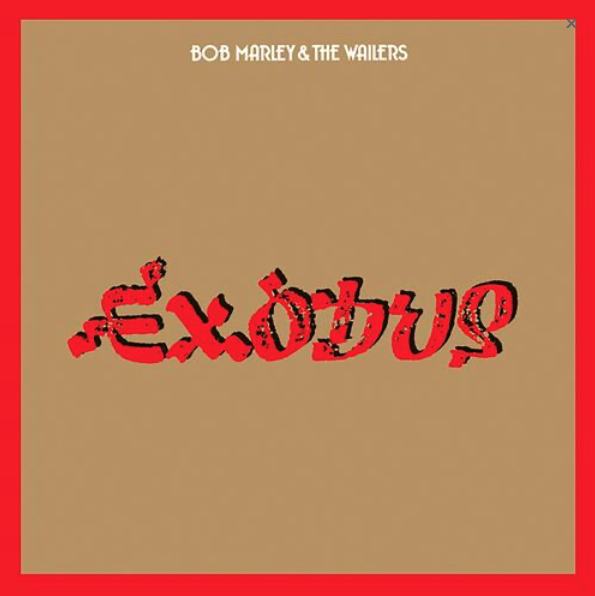

1977’s game-changer Exodus

MARLEY’S RESERVES of positivity would be sorely taxed in the months to come. When The Wailers returned to Jamaica in July 163 Jamaican citizens had already lost their lives to political violence since the start of the year – including 19 policemen – and by the end of 1976 the headcount would top the 300 mark. The mounting pressure was a theme in the island’s music that summer and autumn, explicit in Bob Andy’s War In The City and Johnnie Clarke’s Stop The Tribal War.

Courted and cajoled by both of the main political parties, Marley himself was careful to offer no endorsements, though some had not forgotten his longstanding links with Michael Manley, The Wailers having participated in the political bandwagons that helped bring him to power in 1972. Kudos for Marley at home came with expectations of support: personal, financial, or political.

Nevertheless, following Rastaman Vibration’s international acclaim, Jamaica’s main newspaper, the conservative Daily Gleaner, began portraying Rastafari in a more sympathetic light and lauded Marley as an international ambassador for Jamaican culture. Yet that appeared to make no difference to the gunmen that burst in at 56 Hope Rd on December 3.

“I heard the first gunshot, and then I saw this guy come up through the back door,” remembers Donald Kinsey. “He had on a leather glove, with a gun, and just let loose. After I seen that gun pull back out through the door, I ran out the kitchen and ducked behind one of my Ammo guitar amp cases, and when I peeped around, I could see guns going – just gunshots, man! It sounded like war. Then Bob ran out the kitchen and came through the rehearsal room and went on down the hallway. Don Taylor finally came out and blood was just coming out of him like ketchup. He collapsed right there in the rehearsal room, and I just sat there and waited to not hear any more bullets.”

“Leaving Hammersmith, there were people climbing all over the bus. I felt like, ‘Damn, we’re rock stars!’”

Tyrone Downie

ON DECEMBER 15, Jamaica’s General Election returned Michael Manley’s PNP with an increased 34-seat majority, and promises not to kowtow to foreign influence, but the plummeting economy forced him to sign a deal with the IMF within a year. The 1980 election would prove the bloodiest in the nation’s history, with over one thousand citizens killed through election-related violence (including an MP), and candidates shot at while on the campaign trail. The splintering of the PNP and the unravelling of Manley’s administration ultimately yielded a massive victory for Seaga and the JLP. Meanwhile, Marley’s exile brought him into contact with UK musicians – inaugurating the so-called punky reggae party – and the short-term result would be June 1977’s Exodus album. His music would forge forwards, and look increasingly to the world, the assassination attempt part of his ever-augmenting aura.

“I have no doubt that all of it was ordained by Almighty God,” says Donald Kinsey, with absolute finality. “Everything that happened, the way how it went, it was for a reason and a purpose.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 274

Images: Getty