Mojo

FEATURE

The Outlaw

How do you survive five decades of sheer rock’n’roll excess? “No one here gets out alive, so why think about it?” snarled an unrepentant Lemmy in 2011. And so, Motörhead’s eternal champion of immoderation, guides us through a life of clamorous hedonism…

Motörhead frontman Ian Fraser Kilmister (aka Lemmy), November 2010.

I F I DIDN’T DYE MY HAIR AND BEARD I’D LOOK like Willie Nelson,” admits Lemmy with a self-deprecating cackle. Sitting with MOJO backstage at De Montfort Hall, Leicester in 2011, as he prepares to turn 65 on December 24, Lemmy still wears his excesses better than most.

A quick scan takes in an ursine head on broad shoulders, long, skinny legs and a pair of clumpy, intricately stitched cowboy boots. Black and silver are the only colours that matter, and, his Ace Of Spades tattoo and smoking Marlboro Red aside, you can see why Alice Cooper refers to Lemmy as “Captain Hook”.

Tonight, just as he has done for the best part of the past 50 years, the man born Ian Fraser Kilmister in Stoke-on-Trent will be grafting at rock’n’roll’s coalface, gruffly piloting Motörhead though another night of thunderous excess. But if the decibels and Lemmy’s taste for amphetamine sulphate have sometimes stolen the headlines, it’s worth remembering that his musical education has been thorough and wide-reaching, beginning with his love of Little Richard, encompassing a life-changing moment watching The Beatles at the Cavern club at the age of 16, not to mention his stint working for Jimi Hendrix. He can, of course, also play the crap out of a distorted Rickenbacker bass, but it’s his highly-attuned bullshit detector, his uncompromising approach to life and his ability to blur the lines between rock’n’roll, psychedelia, punk and metal, one senses, that has led to him being revered by fellow musicians as diverse as Slash, Jarvis Cocker and The Clash’s Mick Jones.

Lemmy’s dressing-room betrays one or two other preoccupations: a fruit-machine custom-built in Germany tours with him, and a well-thumbed copy of History Today magazine nestles alongside a jar of Marmite and some reading glasses. “’Scuse fingers,” he says, plinking ice cubes into two tall glasses and furnishing MOJO with a quadruple Jack Daniel’s and Coke. Always mirror your interviewees, they say, but that may not be wise when your subject has the constitution of an ox. That said, his has been a life less ordinary, and he commences to furnish us with a guided tour of it…

The Ace Of Spades: Lemmy and Motörhead perform at Glastonbury 2015

A-LOP-BAM-BOOM! – 1956

THE ANGLESEY PEACE is shattered as the young Ian Fraser Kilmister is enthralled by the sheer power and exoticism of Little Richard. Born in Burslem, Stoke-On-Trent, on Christmas Eve, 1945, the Artist Later Known As Lemmy moved to North Wales at the age of 10 and attended Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones secondary school where his lifelong pact with rock’n’roll began.

“I got into him properly around 1956-57 when he had hits with Lucille and Good Golly Miss Molly. Before that there was only Rosemary Clooney, but when Richard came along we knew he was ours. Bill Haley was first, but we knew it wasn’t him: a fat guy with a kiss curl and those terrible loud-check jackets. Little Richard credited Big Mama Thornton with a lot of his vocal style. He was one of those gospel shouters too, but he took that and turned it in to rock’n’ roll, and you can’t argue with that. I’d hear him on Radio Luxembourg, but you were always fucking with the tuning dial, trying to stop him fading away. There was a lot of mystique, because you never saw pictures. We didn’t know if they were black or white, these people. Chuck Berry – you didn’t know. We got pictures of Buddy Holly, because he was white and safe and the powers that be liked him. They thought, ‘Look at those glasses – he can’t do any harm.’ He did, though – Buddy was my second favourite. A few years back I saw Little Richard when my other band, The Head Cat, played up at Green Bay, Wisconsin. He did 10 bars of Good Golly Miss Molly, and then started handing out Bibles. That’s not what I’m after, you know?”

MORE TEA, VICKER? – 1965

HAVING PAID his dues with R&B act The Motown Sect, Lemmy joins The Rockin’ Vickers, another Blackpool-based outfit. Their early live set includes songs by The Beach Boys and Huey ‘Piano’ Smith, and they will go on to work with producer Shel Talmy (The Kinks, The Who). Indeed, it’s Talmy who overseas The Vickers’ final 45, a take on the Ray Davies-penned Dandy which rises to Number 93 in the US charts. The group also become curiously popular in Finland and are one of the first bands in England to utilise double bass-drums.

“We wore dog collars, which was kind of ironic. My old man was a vicar and he fucked off when I was three months old. My mother never went to church and she never took me, so I didn’t give a fuck. With the Vickers we made £200 a week each free and clear. We were nothing south of Birmingham, but north of there we sold out the Locarnos with the revolving stages. It was great: screaming chicks tearing your clothes off and going at your hair with scissors – pretty crazy when you consider that you couldn’t buy alcohol on the premises. Then one day the taxman came by. He had a Homburg hat and a clipboard, and we were lying around with chicks draped over us. He says, ‘You haven’t filed a tax return in three years – I’m taking possession of your speedboat and those three Jags outside.’ Harry [Feeney, aka ‘The Reverend Black’; singer] goes, ‘Sorry, no can do – I just signed everything over to this chick here.’ In the end we got the guy drunk and he lost his job. Working with Shel Talmy was great, but he couldn’t see very well. You’d hear this crash from the other room, then: ‘Ow! Fuck me!’”

“The taxman came to reposses our speedboat. We got the guy drunk and he lost his job.”

Lemmy

’SCUSE ME WHILE I KISS THE SKY – 1967

LEMMY MOVES to London, where he is befriended by Ronnie Wood (then in The Birds), later moving to the floor of Jimi Hendrix’s roadie, Neville Chesters. A job humping gear for Hendrix, Pink Floyd and others brings in £10 a week, and night after night, Lemmy sees Jimi at the height of his powers. He repairs Jimi’s stomp-boxes with tape and string – and learns that you can play a coherent show on two tabs of acid.

“Acid didn’t take any prisoners: you put your mind at its disposal. The best trips were when I realised there was more to it than religion and a lot less to it than God. Hendrix had met [underground LSD guru] Owsley Stanley in California and brought some tabs with the little owls on them back to the UK, so my introduction to acid came from Jimi’s roadie, Neville. I took a whole pill, not realising it was four trips, but fair play to Neville: he came with me at the same dosage. It was 18 hours of Technicolor explosions: Bang! Bang! Bang! Then halfway down we went to the Speakeasy and saw Keith Emerson chucking fucking knives at his Hammond with The Nice. Jimi was just the best: absolute control of his guitar, a total gentlemen, and a real boost to be around. I only knew him in ’67, but when he went back to the States The Black Panthers fucked him around, saying, ‘What are you doing playing with those honkies?’ I can’t listen to the Band Of Gypsys album he recorded with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles at the Fillmore East. People swear by it, but that’s not Hendrix for me.”

KING OF SPEED – 1971

AFTER A brief, if fruitful spell with tabla-toting psychonauts Sam Gopal (he wrote much of 1969’s rated album Escalator), Lemmy “bluffs” his way into Ladbroke Grove-based space rockers Hawkwind. Quickly proving his worth, he goes on to sing lead on the band’s biggest hit, Silver Machine. As well as leader Dave Brock, his bandmates include six-foot-tall dancer Stacia Blake, and resident poet/lyricist Robert Calvert. Lemmy tours the US with Hawkwind for the first time in November 1973, and that same year their double live album, Space Ritual, reaches Number 9 on the UK charts.

“I listened to Space Ritual on the bus the other night and it was fucking great. That’s how Hawkwind actually sounded. The studio albums don’t really get it across, although Hall Of The Mountain Grill comes close. Before I joined the band in August 1971 I was a dope dealer, but then I got busted and they confiscated my gear and I had to give it up. Being in Hawkwind was one of the best times in my life. I was still really young, then. I had this amazing rapport with Dave Brock on-stage, and I’ve never had it with anybody else since. We could be facing in opposite directions and we’d still change note at the same time. We just knew. It was unfortunate that there was so much drug snobbery in Hawkwind; a lot of people going, ‘Oh, we only do organic drugs.’ Actually, there’s no such thing. By the time you get whatever it is it’s already been through about six people, two of whom have definitely cut it with something other than Shredded Wheat, you know? But I would never have left Hawkwind if they hadn’t fired me.”

Silver Machine: Hawkwind c. 1973, (L-R) Nik Turner, Dik Mik, Del Dettmar, Simon King, Dave Brock, Lemmy.

LIVE TO WIN – 1975

RELATIONS WITHIN Hawkwind fray when Lemmy’s bandmates abandon him by the side of the road in Niles, Michigan, not realising he’s been mugged for his new Spotmatic camera. His dismissal follows five days spent in jail after arrest for drug possession at the Canadian border. What the authorities think is cocaine is, in fact, speed. Loopholes in Canadian law see Lemmy released without charge. Now 30, he forms Motörhead, taking the name from the last song he wrote with Hawkwind.

“Did I feel I had something to prove to Hawkwind? Oh yeah. In a band as druggy as that it felt a bit rich to be sacked for doing the wrong ones. But I just wanted to keep on working. The first Motörhead line-up with Larry [Wallis; guitar] and Lucas [Fox; drums] was when we were still called Bastard, and it wasn’t really happening. Larry left on the eve of our fast few shows, which was the best thing he ever did for Motörhead. The first gigs with Eddie [Clarke] and Phil [Taylor] were when everything coalesced. We played some absolute blinders, we’d come off-stage feeling 10-feet tall. Eddie wasn’t on our first record, On Parole, the one that United Artists rejected [in 1975 and finally released in ’79], but by the time of Overkill [March 1979] we were starting to get our sound together. Motörhead were on the up just as Hawkwind were on the way down, which was fun. It was like, Ha! Told you so!”

OVER THE TOP – 1980

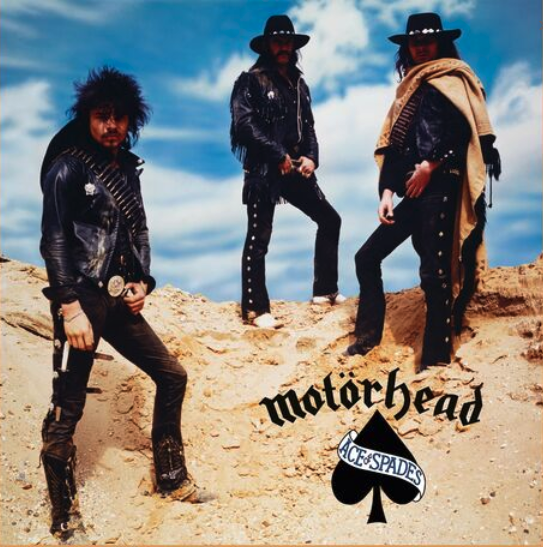

EXISTING ON a diet of Jack Daniel’s, Special Brew and speed, Motörhead release their definitive album, Ace Of Spades, in November 1980. It reaches Number 4 in the UK. A subsequent live album, No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith, soars to Number 1 the following year, its playful title entering the lexicon of touring bands everywhere. The Ace Of Spades cover, shot at a sand quarry in South Mimms depicting three black-clad gunslingers, cements Motörhead’s image.

“Ace Of Spades is unbeatable, apparently, but I never knew it was such a good song. Writing it was just a word-exercise on gambling, all the clichés. I’m glad we got famous for that rather than for some turkey, but I sang ‘the eight of spades’ for two years and nobody noticed. When No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith went to Number 1 it made a difference financially, but a lot of it went back into the show. We had this giant Iron Fist that was supposed to open up, but always got stuck in a V-sign. That line-up of Motörhead looked unbreakable for a while, but then Eddie broke it. I did a cover of Stand By Your Man with Wendy ‘O’ Williams of The Plasmatics, and he didn’t like that. We were in New Orleans and Eddie was co-producing, but Wendy took about nine or 10 takes on her vocal and Eddie went, ‘Bollocks to this,’ and quit, just fucked off. It was petty squabbling, really, and I thought Wendy did a great job in the end. Not everything good is instant, right?”

1980’s Ace Of Spades

GOOD TIMES, BAD TIMES – 1983

LEMMY SHORES up Motörhead with a temporary recruit, but ex-Thin Lizzy guitarist Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson’s wearing of shorts and ballet shoes live doesn’t quite fit the image and there will be many line-up changes ahead. Lemmy doesn’t know it yet, but the period’s more enjoyable pre-Robbo collaborations, with Wendy ‘O’ Williams and with Girlschool on the 1981 hit EP St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, will also come to seem poignant.

“When Eddie left there was no big crisis, we just had to be pragmatic. We were stuck in New York running up hotel bills with a tour to do, so we got in Robbo. We made a good record together [1983’s Another Perfect Day], but he would work on one solo for 10 fucking hours, wipe it, and then start again. Plus, he always wanted to let people know he was a star guest, which wasn’t quite what we were after. Truthfully, it’s the women that I’ve lost I think about, not ex-members of Motörhead. Wendy ‘O’ Williams [who committed suicide in 1998, aged 48] was a great woman. Fucking mental. And Kelly Johnson from Girlschool – she died young as well [to cancer in 2007, aged 49], which was a terrible, terrible shame. I had a small affair with Kelly. She was a good-looking girl and a great guitarist. People used to say, ‘She’s all right for a girl’, and I’d be like, She’s better than you, motherfucker! On a good night Kelly played like a young Jeff Beck. Rock Goddess were fantastic, too. I’m pro-girls in general because I was brought up by my mum and my grandmother. Do I like American women? I like all women; I don’t care where they come from. Most of the time I don’t care where they’re going, either.”

CALIFORNIA SUN – 1991

LEMMY PARTS company with manager Douglas Smith, then swaps the St Mortiz Club, Wardour St, for the Rainbow on Sunset Strip, Los Angeles, where he is crowned by LA’s metal faithful. He lives in a cramped two-bedroom apartment that he rams to the rafters with war memorabilia and Motörhead-related “crap”.

“I hate it when people are snobby about LA. It’s bollocks. Think about it: the weather’s a lot better and the chicks wear less clothing because of this. When I moved over it was like Hendrix in reverse; I got a lot more respect in America than I did at home. My apartment’s definitely too full, but most of the time I prefer being on the road, because that’s where you prove yourself. I’d probably be happier in a bigger apartment, but I can’t bear the thought of moving all that shit, and my rent’s only about $1,000 a month. What I miss most about England is the cheese. In America they can’t make cheese to save their life. So I miss Cheddar and I miss 10, maybe nine people over here. They’re girls, mostly. This place is certainly not the England I was born into, or even the one I used to work in. New Labour or the Tories? Christ, what kind of a choice is that?”

“I’m glad we got famous for that rather than for some turkey, but I sang ‘the eight of spades’ for two years and nobody noticed.”

Lemmy

WE’RE NOT WORTHY – 1995

METALLICA CELEBRATE Mr Kilmister’s half-century by dressing-up as ‘The Lemmys’ and playing a set of Motörhead covers at the Whisky A Go-Go, LA. In 2004, Lemmy and Motörhead returned the compliment, covering James Hetfield and co’s Whiplash for the album Metallic Attack: A Tribute To Metallica.

“It’s lovely to get that kind of respect. Hopefully, it proves you did something right and it makes a change from the tabloids asking you how many groupies you’ve slept with. For a band as big as they are, Metallica always give something back to the people that influenced them in the early days. When they dressed up as me they all had my ‘Ace Of Spades’ tattoo drawn-on in black marker, but it was on the wrong fucking arm. They played 45 minutes of Motörhead songs, sometimes better than we could do them, but maybe not with quite so much attitude. Motörhead getting a Grammy in 1995 for our cover of Whiplash was kind of ironic. The powers that be stuck the knife in even giving me an award, but I appreciate a nod.”

WE ARE MOTÖRHEAD – 2010

LEMMY RELEASES his 21st studio album with Motörhead, then tours The Wörld Is Yours with Welsh guitarist Phil Campbell (a Motörheader since 1984), and Swedish drummer Mikkey Dee (who joined in 1992). Film directors Greg Olliver and Wes Orshoski release the Lemmy documentary, which deals with the man’s accomplishments and also sees Motörhead’s seemingly indestructible leader contemplating life…

“My son Paul is definitely my greatest achievement. He’ll outlive all the shit I’ve done and hopefully make a name for himself and have kids who make their names. Paul’s mum lost her virginity to John Lennon, and yet she called our boy Paul. I’ve always wondered what was behind that – was she trying to get to Paul through John? As far as professional achievements go, I’m most proud of No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith getting to Number 1. It’s that and that Grammy, but it would have meant more if it was for something Motörhead wrote. Staying alive – I’m quite proud of that, too. The legs aren’t as good as they used to be, but the heart murmur thing is cured and I feel OK despite the diabetes. I don’t bother to reflect on mortality – nobody here gets out alive, so why think about it? I just hope that, when I do go, it’s quick (laughs). I’d like a Number 1 record in America. It’s not going to happen but a man can dream. Shows in China, India and Africa would be good as well. I like going somewhere where you have something to prove. Apart from that…”

This article originally appeared in issue 207 of MOJO

Words: James McNair Images: Getty