Mojo

FEATURE

“I’m a musician, I’m not a war hero. It’s nothing to get big-headed about”

He cut his teeth in honky tonks, usurped Elvis and inspired The Beatles. Following the sad passing of Duane Eddy aged 86, MOJO revisits our 2010 interview with The King Of Twang. “By golly, I did something good!” he tells Phil Alexander.

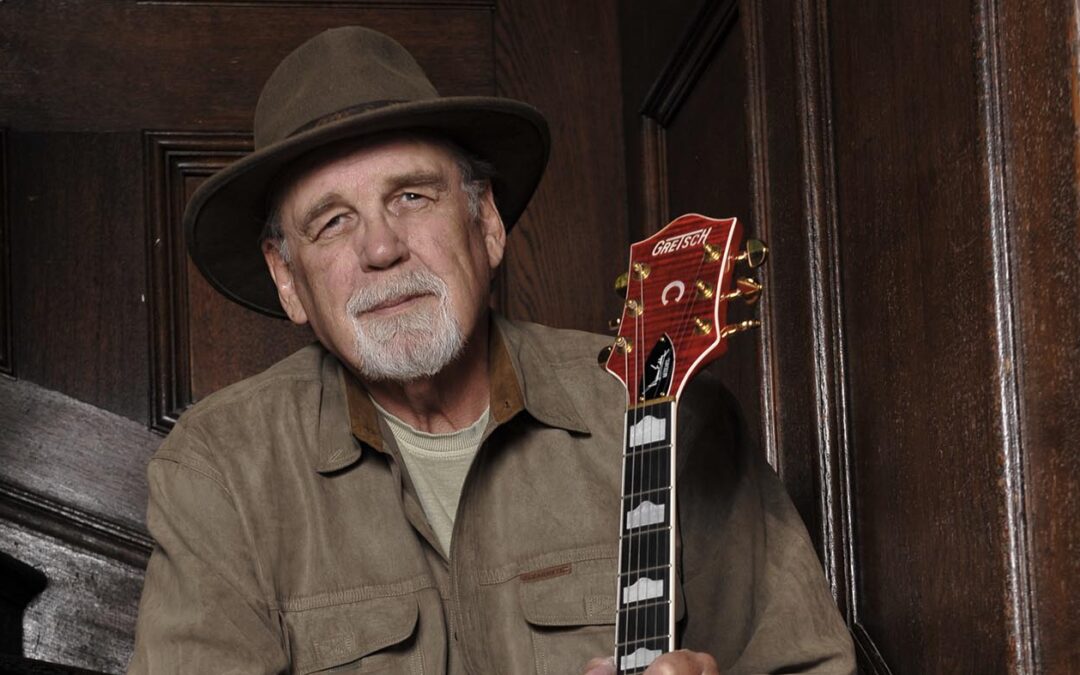

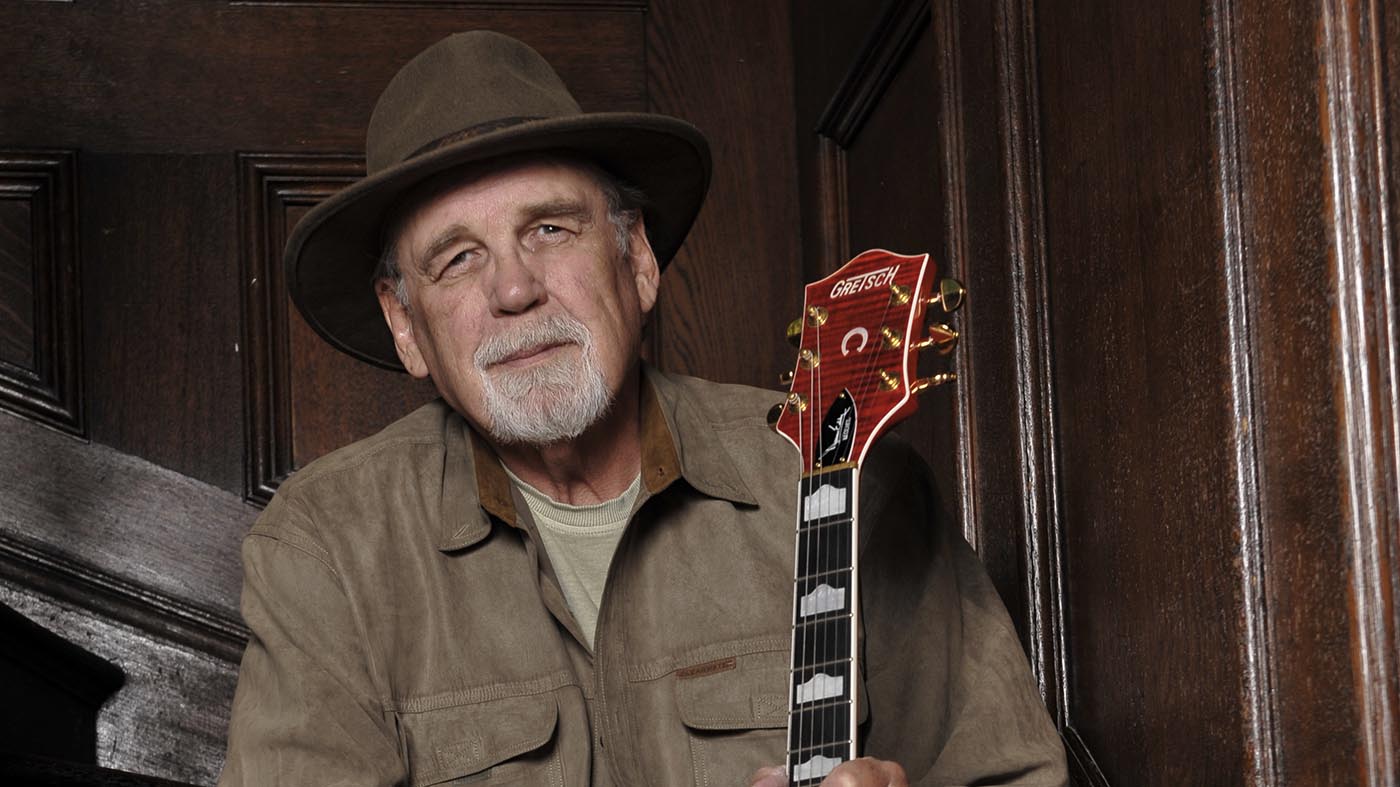

Rebel-‘Rouser: Duane Eddy, London, June, 2010,

IN AN UP-MARKET INDIAN RESTAURANT in London’s West End, few notice the bearded American gentleman with the cowboy hat who sits quietly with his wife enjoying a deliciously spicy vindaloo. The 72-year-old does little to draw attention to himself, washing down his curry with a cooling bottle of Cobra lager before repairing outside for a post-meal cigarette. Then again, Duane Eddy has always been an unassuming character.

Despite scoring in excess of 15 major US hits between 1958 and 1963 (a feat unheard of for an instrumentalist at the time) and dethroning Elvis Presley as the Number One Musical Personality in a UK magazine’s readers’ poll in 1960, the guitarist has little time for airs or graces. Indeed, a conversation with the man is full of examples of his genial humility.

“I’m a musician. I’m not a philosopher or a scientist, or even a war hero or a cop. I’ve entertained a few people but it’s nothing to get big-headed about,” he reasons. Yet for all his modesty, Eddy remains the most successful instrumentalist to emerge from the rock’n’roll era, the records he cut with his friend and mercurial producer Lee Hazlewood helping to shape the pre-Beatles world by placing his musicianship centre stage.

Tracks like Rebel-Rouser (his first Top 10 hit, and the song which begat the name for his backing band, The Rebels), Forty Miles Of Bad Road and the immortal Peter Gunn have thrilled generations of fans and musicians alike – a point evident at this year’s MOJO Honours List when life-long admirer Bill Nelson presented his hero with the MOJO Icon award while clutching his original copy of Because They’re Young, Duane’s life-altering 1960 single, as the likes of Jimmy Page, Roy Wood, Jarvis Cocker and Richard Hawley hollered their approval. In fact, the latter is the latest in a long line of musicians to work with Eddy, with Duane set to record a new album in Hawley’s native Sheffield.

Eddy’s eternal appeal lies in his ability to switch between reverb-soaked raunchiness and impossibly elegant six-string flurries, his style being based on a love of jazz, blues and country music – most notably the playing of Nashville legend Chet Atkins – and his translation of those genres into the rock’n’roll idiom.

“I said to Lee Hazlewood one day, Y’know, I’m playing rock’n’roll but my heart’s in country,” says Eddy, reflecting on his modus operandi. “And Lee said, ‘Well, just think of it as country music with drums.’ And that’s what I did…”

“The Beatles said they were influenced by me, then it was people like Bruce Springsteen. It makes me think: By golly, I did something good.”

You were born in New York in 1938, so what was the first music you remember hearing?

My parents had a little portable record player, they’d play these big old 78s. The first one I remember was Gene Autry. That and Jimmie Davis, You Are My Sunshine. At around five I started playing guitar, learning chords that my dad showed me. Then I lived in upstate New York and I watched Gene Autry/Roy Rogers movies for 10 cents on a Saturday. The other kids would run and get their soda when the singing started, but I’d stay glued.

And what was the first song you tried to play?

I was about nine when I got into Hank Williams Sr and tried to sing his songs. When I was 12, I got up at the school assembly talent show and sang [Williams’] Long Gone Lonesome Blues and It Is No Secret, which is a Stuart Hamblen song. After that I went on a radio show with the kids from the class, and played The Missouri Waltz. So I actually played my first instrumental on a radio station in upstate New York when I was about 12, I think!

At 13 you moved to Arizona with your family. What impact did that have on you?

I fell in love with the desert. It was so open and big and beautiful, with cactus and the mesquite trees. There’s nothing that beats that feeling of when a storm is coming. You can smell it long before you see it, and when the wetness hits that desert sand, you would just smell that smell. It’s exotic, just amazing. Musically, I could always go out into the desert with just an acoustic guitar and write a song.

What was the first band you assembled? And what did you sound like?

Well, there was no rock’n’roll in ’53 or ’54, it was either country or pop. Then, Bill Haley came along with Rock Around The Clock in ’55 and stirred things up, and so did Elvis with his Sun recordings. The year before that, I was going to high school in this little town called Coolidge. I’d been there a couple of months and my father ran into the local radio DJ and told him I played. He said, “Bring him out and we’ll record a little song on him.” I went and played a Chet Atkins song [Spinning Wheel] and he played it on his early morning show. Then, this kid named Jimmy Delbridge came running up to me at school and says, “You wanna come over to my house and play music?” “Well, sure.” He played piano and I played guitar and we sang country songs. That was our first group. His brother played a little banjo, another friend of mine played a little bit of rhythm. Soon after that, the DJ I knew left town for a bigger market and we got this new guy that had just gotten out of broadcasting school: Lee Hazlewood.

How did your relationship with Lee develop?

He came and heard us play, and he wanted to get in the bigger [radio] market in Phoenix but didn’t know quite how to go about that, so he decided to become our manager. By 1955 he was doing real good. He had a live show on Saturday and Jimmy and I would do a 10-minute slot there. The station manager figured he’d fire Lee and do his own show. Lee was wondering what to do when this guy came up and said there was an opening at KRUX in Phoenix, and if Lee wanted the job he had to start Monday. Lee pretended he wasn’t sure about it, but he took the job and turned up on that Monday. One day we were in the car park at the radio station and this local country singer came up to us and said, “There’s this kid who’s tearing this up down South. I brought you some records, Lee. Maybe you want to play him.” So we all trouped into the studio and heard Elvis for the first time.

Lee loved him but he almost lost his job for playing him all the time on a country station. People would call up and say, “What are you playing that race music for?” And they couldn’t learn his name. The lady at the local record store called up one day saying, “Lee what are you doing to me? Who’s this guy Arvis Barsely? And where do I get these records from?” In early ’56 Elvis hit with Heartbreak Hotel and it became a real monster. At that point Lee decided he wanted to try and record with me and Jimmy.

So that was your first record, released under the name Jimmy And Duane in 1956?

Yes. Jimmy was very involved with the church. After we got the record made Jimmy came in and says, “I got saved.” “Saved from what?” “Saved in church.” “Oh, well, congratulations.” He said he couldn’t sing worldly music any more so Lee was sitting there with 400, 500 copies of this record he’d made and paid for and couldn’t do anything with. That was Soda Fountain Girl with I Want Some Loving Baby. Both songs were a bit corny. Lee had written one song before that he’d actually copyrighted but this was the first attempt at producing and writing for an artist.

Anyway, I was playing in Phoenix with The Sunset Riders and Buddy Long when Lee cut another song, The Fool, with a singer called Sanford Clark. He put it out on a local label [MCI] and Dot Records took notice and put it out properly. It became a Top 10 hit but Lee never lucked out with anything else he produced. Finally, he ran out of people to work with and, because I wasn’t a singer per se, he said, “Let’s write an instrumental.” That’s when I went home and wrote Movin’ ’N’ Groovin’, in November of ’57.

How did your sound develop? Was it just by playing live endlessly as a Sunset Rider?

Yeah, with Buddy Long. Just playing the honky tonks. Some of them were nice halls, but we also worked the bad places. One night we drove up to one honky tonk, suddenly Buddy slammed on the brakes and I nearly hit the windshield. “Look over there!” He points over at a sign. It says, “Dance and fight to the music of Buddy Long.” He was laughing so hard, I was too. So we played for them to dance and fight. There’d usually be about one good fight a night at those places. We just played through it, hoping the rest of the club wouldn’t notice. Usually they didn’t.

Movin’ ’N’ Groovin’ on the Jamie label wasn’t a huge hit. Rebel-Rouser, your second single, went Top 10. Suddenly you were a star. What effect did that have on you?

That was the summer of ’58 and I took off in my car with three musicians: sax, bass and a drummer and did The Dick Clark Show in Philadelphia. We did promotion down the East Coast a while. We did another show, Dick Clark on location for his Saturday night show. It was on at seven o’clock and we’d have 63 million people watching us. These days it’s unheard of. I spent three months on the road and it was fantastic. Then I got home, I hadn’t changed, but I realised everyone else had. People wanted to know me. I found it strange.

Your first album was Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar Will Travel in 1958. Who coined the word ‘twang’?

We were recording in Phoenix, starting my first album, and one of the guys said, “Man, that guitar sounds twangy.” And [Hazlewood’s business partner] Lester Sill fell down laughing. He’d never heard that word and it just became a running joke. “Is that twangy enough?” So we finished the first album and named it Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar Will Travel. To be honest, I never really liked the word. I thought it was kind of corny and rather undignified, but at the same time so many people liked it I just shut up and went with it.

What were you and Lee striving to do with the records you were making?

What we were trying to do was simple: to cut a hit record. That’s all we were after and we were quite successful at that.

So much so that in 1960, you were voted Number One Musical Personality by NME readers in the UK, deposing Elvis from the top slot. How did Elvis react to that?

With Elvis, I never had that conversation with him about that ’cos I met him for the first time in 1971 backstage in Las Vegas. He was just great to me. He treated me really like a peer – which I didn’t feel I was. We sat and talked all night long. At one point he was standing there and I was sitting on the couch, he looked at me and he goes, “Duane!” and he made like he’s playing air guitar. He said “Duane Eddy, you’re too much!” And right on ‘too much’ he did a big Elvis pose with an arm over his head and a twist of the legs – the trademark thing he did on-stage. He looked great. I watched him say goodnight to people as they left and he was just the perfect Southern gentleman. He had impeccable manners and he looked like a knight standing there. Priscilla was there too that night so he was so happy. This was before she left and he became unhappy. He was everything I wanted him to be, but he did have a naïve side to him.

“Elvis said, ‘Duane Eddy, you’re too much!’ And right on ‘too much’ he did a big Elvis pose with an arm over his head.”

You made your film debut in Because They’re Young in 1960 alongside Tuesday Weld and Doug McClure. How did that come about?

It was a Dick Clark film. He and I had become friends. He really liked the group and had us on American Bandstand every time I had a new record out. He wanted Lee and I to come up with the movie’s theme. Then somebody sent Lee the song that became Because They’re Young, written by Don Costa, Wally Gold and Aaron Schroeder. It just blew his mind, he just knew it was a natural hit. He said he sat there from seven in the evening ’til about 11, missed his dinner and everything, and just kept playing it over, listening to it. He decided we’d record it, so we recorded that in United’s Studio B. It was the first time I’d recorded in Hollywood. Then we went over to the Columbia soundstage to record the same song for the movie, and they had a guy named Johnny there who was doing his first score for a movie. His last name was Williams… John Williams [the now-legendary soundtrack composer]. I worked with him and didn’t even realise it. He just conducted the orchestra. I don’t think he said two words to me.

Because They’re Young became your biggest hit in the US, reaching Number 4.

We did the soundtrack for the movie and the theme for it. But my session was a different thing, and that became the hit single. We had strings from the LA Philharmonic and we had a great rhythm section: Shelly Manne on drums, Red Callender on bass and Howard Roberts, the guitar player, was playing rhythm. He introduced me to this new guy I didn’t know and I started to shake hands and he said, “This is Barney Kessel.” I pulled my hand back and said, “What are you doing here!?” and he said, “Just earning a living.” I was such a big fan of his, I couldn’t believe it. After the session Howard showed Barney a guitar he’d just bought and they started playing. Shelly Manne picked up his brushes, Red picked up his bass, and they played Witchcraft for about 10 minutes. It was amazing.

In 1960, you also had a hit with a cover of Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn. Why did you choose that?

We were doing the second album, Especially For You. [Saxophonist] Steve Douglas said, “Duane, I learnt Peter Gunn last night.” I said, “Well, that’s nice.” He thought it’d just be good as an album cut but I didn’t think so. So we forgot about it and we got 11 or 12 songs done. We had room for one more. Lee and me were sitting there discussing what we could do and Steve wandered over and said, “We could do Peter Gunn.” I thought, “What the heck! It’s only an album cut.” So we figured out the intro, then the riff, and we cut it. It became a single because somebody in Australia in the record company took it from the album and it got to Number 3. Somebody in England noticed that so they released it as a single. It got to the top of the charts. Finally, Jamie noticed this and said, “Maybe we should make this a single in the US.” So that’s how Peter Gunn came to be.

Four years later the British Invasion seemed to kill American rock’n’roll. How did you feel?

It affected me ’cos I suddenly wasn’t hot any more. Every face was turned toward England; every chart filled with English records. I thought, “I’ve had my five-year run.” I was exhausted from being on the road and I was out of ideas. I was in my last year with RCA, I’d done nine albums with them and couldn’t stay on top of the trends any more. They wanted to plan everything six months ahead, so the first album I did was a Twist album and it didn’t come out ’til the Twist [craze] was over. I gave up and thought, I won’t do that again. It’s times like that when you get these weird off-the-wall ideas, like my water skiing album. I thought, “They’re all surfing on the West Coast but what about the middle of the country? They’re water skiing!” So I cut this album (1964’s Water Skiing) with all these water skiing songs in it – the worst-selling album I’ve ever had!

The late ’60s were quite tough for you as an artist…

I could see the writing was on the wall. I loved The Beatles. They had the same excitement as Elvis but I couldn’t do what they did. I did some other albums, went to Warners for a while. I even had a hit with Freight Train in 1970 but it was an Easy Listening chart hit. I thought, “Man, I’ve gone from edgy to easy listening in five years.” So I came to England, and worked from 1968 for most of the year in clubs. During that time I realised I’d got paid about a fourth of what I should have had in royalties. In about 1972 I finally found out the whole story of how much I had been cheated out of things financially.

What were you doing as the ’70s dawned?

I wasn’t very high profile. In 1969 a friend of mine was working a session with the singer Al Martino. Al asked my friend for a country guitar player and he suggested me. I went out on the road with Al but he had just missed my whole boat so at first he had no idea who I was. A couple of reviews upset him a little, but he was always the gentleman about it. They’d write a paragraph about Al and say, “But the real surprise of the night was the bearded guitar player,” and they’d write the rest of the article about me. I felt bad about that but I couldn’t do anything about it. We got through a year of touring, then, halfway through a month’s stay at The Riviera in Las Vegas, he got the part in The Godfather so he paid us off for the last two weeks and went off to film. I toured the Orient that fall. I went to Vietnam, played a couple of weeks there, then back to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Guam.

The Vietnamese tour must have been terrifying, bearing in mind that the war was still going on.

No, actually. I felt completely secure, as long as I was on a base or with our guys. We did have one experience one night where we were in a van when they stopped us at a road block on the way back to Saigon. They told us they were the national guard and they wanted some cigarettes. I thought, well, they were just poor soldiers on the South Vietnamese side; but I wondered why they were wearing black T-shirts. I got back to Saigon and was telling, one of the military guys there about it, and he said, “There is no national guard. That was the Viet Cong.” But apart from that, we were fine.

In 1973 you produced Phil Everly’s solo album, Star Spangled Springer. How would you characterise the ’70s as a whole?

Well, the good thing about that time was that I met my wife Deed in 1973 and from then on it didn’t matter what happened. I was a happy man. We came to England in 1975 and did another hit record, Play Me Like You Would Play Your Guitar, with [UK songwriter] Tony Macaulay. Top 10 all over the world, except for America, where they wouldn’t release it. Then that fizzled out. Tony decided to write a play or something.

In ’86 you collaborated with The Art Of Noise on another hit version of Peter Gunn…

Yes, a friend sent a couple of their records saying, “Could you do something with them?” I listened and I thought, “OK, it’s weird, it’s bizarre but why not?” Then when I talked to them, they wanted to do Peter Gunn. I thought, “That’s easy!” So I flew over and put my guitar on their track and they finished it up. I did publicity for the record and the next thing it’s a chart record everywhere.

You released a self-titled album on Capitol in 1987 featuring John Fogerty, Ry Cooder, Steve Cropper and The Art Of Noise, with Paul McCartney and Jeff Lynne among the producers. How did that come about?

I ran into Jeff Lynne at a festival with The Art Of Noise. He came up to me and said, “I know you’re going to be doing an album after this, so I want you to know I’d be willing to produce, write or play, whatever you want me to do.” So I called him and he says, “Oh man, I’d love to do some- thing, but I’m producing George Harrison’s album.” I said, “Say no more, I understand.” I hung up, and 10-15 minutes later he rings back and says, “I was talking to George about it, he wants to put his album on hold and do yours.” A couple of weeks later we flew to England and went to George’s, and that was a lovely, lovely experience. George was wonderful and had a beautiful place, Friar Park, up there on the Thames. He, Olivia and Dani were there, and we got to hang with them and had a grand time.

And Paul McCartney also got involved…

Yes. Somebody I knew asked Paul if he was interested in doing a track and he said he was. So we went down to The Mill and cut Rockestra Theme in one day. I had to go to Brighton for a Capitol meeting with the distributors to promote the album. Paul was still working on a dance mix of the Rockestra Theme. Suddenly the doors of the meeting burst open and here come Paul and Linda. Everybody went dead silent and Paul walks up to me and he says, “You want to hear the dance mix?” I’m thinking this is a weird place to come and play it for me! But we went outside and he left us to listen to it in the car. We were amazed and enthralled. I couldn’t believe the work he’d done on it. We went back inside and Paul was there having his picture taken with everyone and talking about my new album to the distributors. It was incredibly kind of him.

Richard Hawley is the latest in a long line of your collaborators. So what kind of a record would you like to make with him?

I’m really wrestling with that. I would like to do something new, different and original with Richard. I love that big sound he gets. I’m going to make the record up in Sheffield with him and we’ll see what happens. I’m sure that the combination of the two of us will allow us to do something interesting.

Final question: after all this time, what have you learned?

I’ve learned that life is great. Even though I was cheated out of so much money, people make up the difference. At first, young kids like The Beatles said they were influenced by me, then it was people like Bruce Springsteen. It makes me think, “By golly, I did something good.”

This article originally appears in MOJO 204

Words: Phil Alexander Images: Getty