Mojo

FEATURE

Rock And Roll Heart

Street hustler, heartbreaker – Johnny Thunders remains an icon wherever rock’n’roll is revered, but he was never a bigger star than he was in London, for 18 months at the acme of punk. In 2017, friends and bandmates sifted the man and his music from the junkie mythos, and mourned his fate anew for MOJO. “You always got the feeling that Johnny was hurtling towards something.”

Words by Andrew Perry

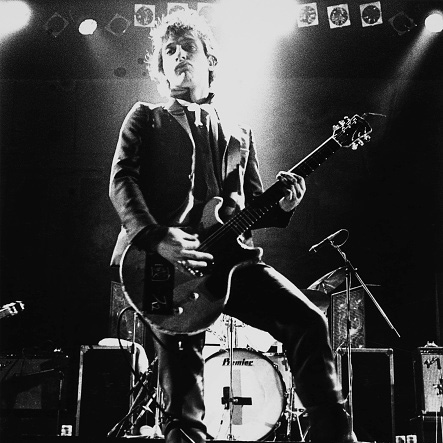

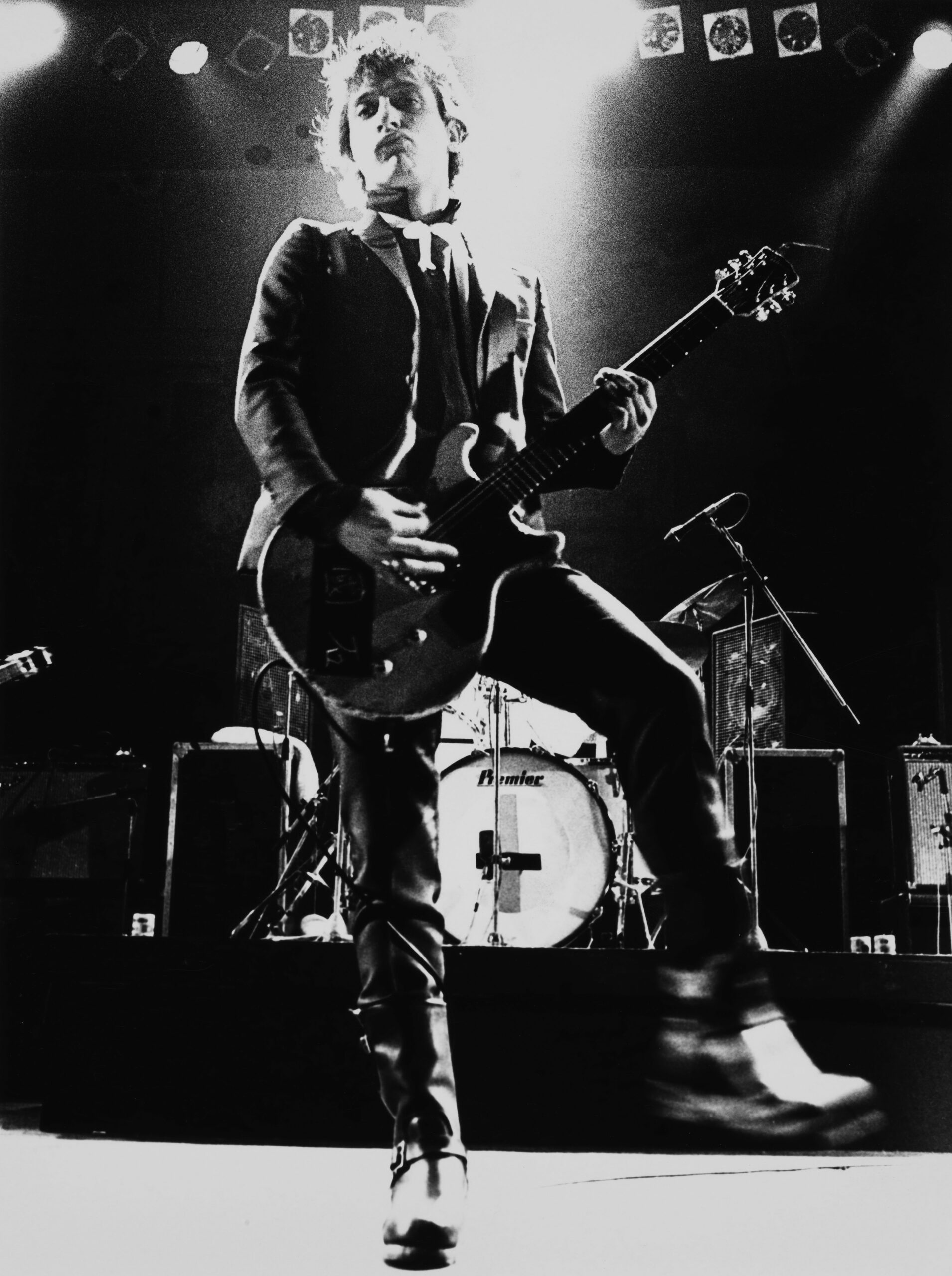

Jet Boy: American guitarist, singer and songwriter Johnny Thunders performing live on stage, UK, 1978.

NO ONE EVER looked more like a rock star than Johnny Thunders. Dressed like a hooker in stack heels, hair teased into something indescribable, he manifested before British eyes on November 26, 1973, as lead guitarist in Big Apple glam-rockers the New York Dolls on BBC TV’s The Old Grey Whistle Test. Presenter ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris called them ‘mock-rock’, but a younger generation were transfixed. .

“We’d seen the Dolls at Wembley, when they supported the Faces [in November ’72],” remembers future Sex Pistols drummer Paul Cook. “They were so throbbing and relentless. Steve Jones [the Pistols guitarist] was in awe of Thunders.”

But under the make-up, the scowl and the violence with which he attacked his six strings, lurked a character of complexities impenetrable to all but those who knew him best. “Johnny could be a monster,” says lifelong friend and collaborator Patti Palladin, “but he was a sweetheart underneath all that.”

Born John Anthony Genzale Jr on July 15, 1952, Thunders was raised by his mother and sister in the Italian-American heartland of Queens. Palladin, a Brooklynite who has rarely spoken about Thunders since his untimely passing in 1991, hung out with him in the crowd at the Fillmore East, watching Jimi Hendrix. “Johnny’s mother used to say, ‘If he was a girl, he’d be you,’” she recalls, dark eyes affectionately twinkling, “‘and if you were a boy, you’d be him.’”

At 18, Genzale joined a bedroom band called Actress, which duly morphed into the New York Dolls. His musical role model was obvious and also ominous: Keith Richards.

“You always got the feeling that Johnny was hurtling towards something which wasn’t gonna end with him being able to do music,” says Peter Perrett, formerly of The Only Ones, who befriended him in London in the late ’70s. “He didn’t seem to take care about his personal wellbeing, and maybe that was part of the appeal.

“But there were other, deeper sides to Johnny – his love and knowledge of rock’n’roll, his sweeter nature – that nobody ever really saw or understood.”

AFTER THE DOLLS imploded on tour in Florida in summer 1975, Thunders and drummer Jerry Nolan formed the Heartbreakers, initially as a trio with bassist Richard Hell, who arrived from a fractious stint in Television with status as the emerging NYC punk scene’s poster boy, and – crucially for Thunders and Nolan – a heroin habit.

Thunders himself had reputedly been turned onto the drug by Iggy Pop circa July ’73, after Thunders started a full-time relationship with LA groupie Sable Starr, while Iggy was dating Starr’s sister Corel. Junkie lore would soon enshroud the Heartbreakers – but in the short term, his band made headway at Warholian NYC hipster dive Max’s Kansas City after poaching second guitarist Walter Lure from debutants The Demons.

“They needed another guitar player,” explains Lure, “because at that point Johnny could only carry it if he wasn’t singing.” When Hell quit to pursue his own band, the Voidoids, Thunders’ combo recruited mild-mannered Billy Rath, who, says Lure, was “a speed freak at that point, but he steadily became a junkie like the rest of us.” He adds: “Back then, it was cool to be one. People didn’t think you were slobbering or collapsing on-stage. Everyone was taking drugs.”

By autumn ’76, unable to land a record deal in New York, the newly rechristened Johnny Thunders & The Heartbreakers had plateaued. Their unlikely saviour: Malcolm McLaren, the English fashion entrepreneur whose first dabble in music had been to guide the Dolls through their second, terminal phase. McLaren’s new charges the Sex Pistols were about to unleash Anarchy In The UK, and he was calling to invite the Heartbreakers onto the Pistols’ first British tour. “We had no idea that the Pistols looked up to Johnny so much,” recalls Lure. “When we arrived, Malcolm took us out to a restaurant, and [the Pistols] were all kind of in the corner, not saying anything, and we later found it was because they were in awe – they were afraid to sound like idiots.”

A couple of hours later, the Pistols were whisked off to Thames TV Studios for a last-minute appearance on The Bill Grundy Show. “Next day,” says Lure, in a still-disbelieving Queens brogue, “we wake up and read the papers – ‘What the fuck is all this? Somebody’s cursed on television, and the whole country’s in an uproar? People are kicking their TVs in?’”

The Anarchy tour’s faltering progress from that moment on has been amply documented, but for Thunders and co it was doubly mind-warping. “We were turning up in Derby and Worcester, not able to play,” says Cook, “and the Heartbreakers were all withdrawing from heroin, feeling shit. They’d be sitting up all night, acting strange, drinking loads of cough medicine, going, ‘Urgh, I can’t sleep!’”

At the few gigs that took place, Steve Jones, The Clash’s Mick Jones and The Damned’s Brian James watched open-mouthed side-of-stage as Thunders summoned a sound from his Les Paul Junior and Fender Twin Reverb that was both primitive and volatile, lyrical and inimitable. By the final cancelled show in Paignton, on December 23, Thunders and co, in Lure’s words, found themselves to be “in the aristocracy of punk bands in the UK”. So, instead of flying off to resume a fruitless struggle back home, they decided to remain in London, with a view to hustling for a British record deal.

On December 25, they joined their touring company at Melody Maker writer Caroline Coon’s house for Christmas turkey, and, on January 11, played the fourth show at UK punk’s first dedicated nitespot, the Roxy in Covent Garden. While the four Heartbreakers returned to New York to collect their possessions, their manager Leee Black Childers brokered a deal with Track Records, home of The Who in the ’60s. Thunders – a Pete Townshend-style powerhouse guitar hero for the punk era – was on course for stardom.

“Johnny’s mother used to say, ‘If he was a girl, he’d be you, and if you were a boy, you’d be him.’”

Patti Palladin

IN A STICKY-FLOORED private dining room on London’s Abbey Road, the mercurial spirit of Johnny Thunders seems to waft through the air, as Patti Palladin and Peter Perrett share their reminiscences.

“Johnny was above the whole punk movement,” says Perrett, who first met Thunders at the second Only Ones gig at the Speakeasy in January ’77. “He was someone who had charisma in any setting, but it gave him an audience. One time, he was on the phone to someone back in New York, and he was going, ‘You gotta come over here – they think we’re professional!’”

“Johnny and Jerry were completely bemused by the whole scene,” adds Palladin, who’d moved to London in ’74. “There they were in their ’50s threads – Mr Fuckin’ Suave – and there’s all these kids running around in binliners.”

Installed first in a tiny shared flat in Pimlico, then in a more palatial affair in Oakley Street, Chelsea, the Heartbreakers were living hand to mouth, and pulling together material for a debut album. Eventually dubbed L.A.M.F., it would boast the fast and furious Born To Lose, I Wanna Be Loved and Pirate Love, plus Chinese Rocks, a solid-gold anthem donated by Dee Dee Ramone. But internal divisions were already starting to appear when Jerry Nolan – on some level, a stabilising, elder-brother figure in Thunders’ life – got himself onto a methadone programme and moved into a girlfriend’s place out in Harrow.

“Jerry used to lose his temper with Johnny quite a lot,” says Perrett. “One time in Pimlico, Johnny asked me if The Only Ones would support the Heartbreakers. He goes next door to talk to Jerry and Jerry goes, ‘But you promised the Banshees they could do it.’ Then you heard shouting, and things being thrown and smashed. It was very much a love-hate relationship.”

The band’s album should ideally have been punched out quickly, tight and bright, but sessions dragged on through summer ’77 at several studios across town, with producer ‘Speedy’ Keen, formerly of Who protégés Thunderclap Newman. With time running out to make its October release date, there were post-production issues with L.A.M.F. which would diminish its potency. Nolan fumed at the muddy mix and initial pressing of 5,000 albums.

It soon transpired that Track’s motives in signing the Heartbreakers had been somewhat shady: in order to continue to receive royalties on The Who’s back catalogue, its bosses Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert had had to prove it was still a functioning label. When they lost a court case to secure those monies, they liquidated the company, with huge debts, casting L.A.M.F. and its creators to the void. “Johnny joked about it all,” says Perrett. “He told me he was gonna change their name to The Junkies. They’d been on Track Records, and the publishing was now gonna be Hepatitis Publishing. Maybe it was just his funny way of flagging up that it was about to fall apart.”

Before the year was out, the Heartbreakers were no more.

Trash: The New York Dolls’ singer David Johansen and Thunders performing live in Los Angeles, California, 1973

IN JANUARY 14, 1978, The Sex Pistols replicated the Heartbreakers’ demise, flaming out in comparable disarray on the opposite side of the Atlantic. With The Damned also no longer operational, Thunders was still handily placed, if he could just get his act together.

He was an icon of the new order, right up there with Iggy. His reverb-overloaded guitar style – which Nolan once evocatively described as “like dinosaurs screaming in the forest” – was referenced by every wretched punk band on earth. Still, the foul-mouthed street-tough façade he saved for the stage. In private, he was very different. “He was that kind of vulnerable, lovely guy,” says Paul Cook, “who attracted people to come and look after him. There’d always be a lady around to take him in, and mother him.”

Indeed, on a fleeting trip back to Queens, he’d married his long-standing girlfriend, Julie Jourden. Says Perrett, “Part of him craved a stability, which he knew he could never adhere to.” Their relationship was fractious: Jourden, says Lure, was “a hard-ass, and they were always having these knock-down-drag-outs, where the police got called.”

When she duly came over to London with her two sons, John Jr and Vito, the latter fathered by Thunders, they moved into a flat above a sauna in D’Arblay Street, in the heart of sleazy Soho. Thus perilously ensconced, Thunders had his next move mapped out.

Recalls Perrett, “Johnny always used to say to me, ‘Chuck out [lead guitarist] John Perry, and let me join The Only Ones. He’d say it half-jokingly, and I’d sort of laugh it off. I think he was looking for someone to bounce off – a Jagger-Richards type thing. Then when the Heartbreakers split up, he asked me to get a band together for him, to start doing gigs.”

For the first night of a residency at the Speakeasy in February ’78, Perrett drafted in The Only Ones’ rhythm section – bassist Alan Mair and drummer Mike Kellie – and Palladin came in on vocals. Billed as The Living Dead, this loosely-arranged revue went on for some weeks, playing songs, old, new and borrowed, with line-ups featuring such admirers as the Pistols’ Cook and Jones, and Steve Nicol and Paul Gray from Eddie & The Hot Rods.

Thunders revelled in this freedom, until one cringeworthy evening when his most wayward apostle turned up, begging to share a stage. Sid Vicious had bought hook, line and sinker into Thunders’ lifestyle and look. When New York groupie Nancy Spungen arrived in London in an ongoing quest to bed Jerry Nolan, Vicious famously embraced her – and her drug habits – with open arms. His fanaticism and choice of girlfriend were bad enough, but to a guitarist for whom ‘chops’ were all-important in pulling off an ultra-cool stage act, Sid, newly freed of his duties in the Sex Pistols, belonged back in the moshpit whence he came.

“Sid was a nice guy, just a kid really,” smiles Palladin, “but he was in no way a musician. He came down to soundcheck, and he was going, ‘Oh, can I play now?’ and Johnny was turning to me, going, ‘What the fuck am I gonna do?’”

“I felt sorry for him,” says Perrett. “I persuaded Johnny to let him play, on condition that the roadies disconnected his amp from the speakers, so no actual sound came out.

“When we came on to do our set, Johnny had convinced Nancy to introduce us, topless. Sid was like a kid, upset that his girlfriend was up there being loud and topless, but for the first two or three songs, Sid was really jumping around enthusiastically. During the third song, he must’ve noticed there was nothing coming out. I was amazed it took him that long.”

“Johnny was above the whole punk movement. He was someone who had charisma in any setting.”

Peter Perrett

REMEMBERING THOSE NIGHTS in early ’78, all concerned go a little misty-eyed. “They were magical because it was all so loose and spontaneous,” says Palladin, “which was very Johnny.” At one of the later shows, Dave Hill, young boss of Warners-affiliated Real Records, who’d just signed Palladin’s emigrée pal Chrissie Hynde’s band, The Pretenders, approached Thunders with a view to replicating the Living Dead format on a star-studded solo album.

Perrett’s wife Xena brokered a deal for “a few thousand quid”. Again, Thunders entrusted Perrett with assembling the ensuing sessions, either side of an Only Ones tour supporting Television, with help from debutant producer Steve Lillywhite.

As well as firing off favourite covers from the Speakeasy, such as a Palladin-enhanced take on The Shangri-Las’ Give Him A Great Big Kiss, Thunders unveiled some more sophisticated material he’d been working on, including You Can’t Put Your Arms Around A Memory – a song destined to be acknowledged one of the best of any rock’n’roll era. “For him,” states Palladin, “…Memory was about capturing more than the typical frontline rhetoric of youth. It defaults instead to his background, the whole Italian family thing, which came with a lot of compassion, pain and pathos in his case.”

Another anti-anthem, So Alone, found him, in Perrett’s words, “almost pleading to be given a life that’s worth living”. At Island’s in-house studio in Chiswick, the track elicited an impassioned if somewhat unsteady performance from its author, who keeled over into Mike Kellie’s drum kit in the closing seconds, thus rendering the take unusable.

When Perrett disappeared on tour, Lillywhite corralled sessions with Cook and Jones. These yielded London Boys – Thunders’ swingeing riposte to the Pistols’ New York – but the Perrett-Kellie and Jones-Cook camps only came together for one late-night romp through Otis Blackwell’s Daddy Rollin’ Stone, where they were joined by Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott, a Speakeasy regular, and Steve Marriott, the erstwhile Small Faces frontman, with whom Thunders had first collided at a party during one of the Dolls’ early-’70s UK visits.

In July ’78, the rolling sessions had to wind up, as Thunders’ residence permit was up. Again, there was a rush to finish the album for October release, with a star-studded show booked to coincide at London’s Lyceum, and while the album was now titled So Alone, there apparently wasn’t time for the track it was named after to be fixed.

Come October 12, the Johnny Thunders All Stars convened at the Lyceum, with bonus attractions like The Pretenders’ James Honeyman-Scott on keyboards, but without two of its biggest names. “Steve and I went to rehearsals,” says Paul Cook, “and Johnny was in a bad way, nodding out. It was starting to get pretty dark, and we’d had enough – neither of us was into drugs at that point. Malcolm was onto us, going, ‘You’ve gotta get away from him.’”

Unpredictable as ever, Thunders played a blinder, but there was a sense of the audience chafing at his more sensitive material. “It just didn’t fit with what people had come to expect of him,” shrugs Perrett, “and it must’ve felt to him like he was stuck with a punk audience.”

There was much, much worse to come. “When I get home from the show,” says Palladin, “my phone rings and it’s Johnny. I’m like, What the fuck? He’s like, ‘I just spoke to someone in New York, and you’ll never believe this – Sid killed Nancy at the Chelsea.’”

While we will never know what happed that night, punk’s days of innocence were over.

Born To Lose: Johnny Thunders And The Heartbreakers with a Ford Transit tour van, St Albans, United Kingdom, 1977.

AS OUR THREE-HOUR conversation with Perrett and Palladin winds up, Pedro Mercedes, boss of Thunders’ reissue label Remarquable Records, arrives with artwork proofs for a forthcoming re-release of So Alone, including unused shots from the original album cover session. Back in ’78, Johnny’s label chose to depict him as slit-eyed, wasted and backed into a corner, but they also had close-ups of him looking bright-eyed and cheeky. Obviously, late-’70s marketing wisdom dictated there was nothing to be gained by presenting Thunders at his best – it was the half-dead junkie that the public wanted.

“Drugs are like the evil grandmother hanging over Johnny’s legacy,” observes Walter Lure, who in the ’80s left-turned into a career on Wall Street and duly beat addiction. Yet the fact remains that, in his lifetime, Thunders was totally unabashed about broadcasting his narcotic predilections.

“I sort of admired his brashness, in being so open about it,” argues Perrett, “but I also thought it was foolish, because it attracted a certain ghoulish interest, rather than people appreciating the art for what it was.”

After his frantic 18 months in London, Thunders’ plan was to relocate to New Orleans, and, says Palladin, “basically to play with a bunch of brilliant old blues musicians. In his head, he was hearing a horn section.” None of that came to pass as, for the next 13 years, he wandered between Detroit, Paris, Sweden and beyond, playing with pick-up bands, with the reformed Heartbreakers, with Wayne Kramer in the short-lived Gang War, or sometimes, for a full cut of the door money, solo on acoustic guitar.

Says Palladin, “His attitude became, ‘If you’re really paying this money, happy to see me play fucked up, hoping this is gonna be the gig where I actually die on-stage, then fuck you!’”

On April 22, 1991, a 38-year-old Thunders finally made it to a hotel in New Orleans’ French Quarter. “But he didn’t find what he was searching for,” says Palladin, “because within 24 hours he was dead.”

A somewhat inconclusive autopsy showed that he hadn’t died from an overdose, but was suffering from an advanced stage of lymphatic leukaemia. There was no mention that his passport, guitar and suitcase, plus $20,000 in cash, had been taken from the room, raising a suspicion, not officially acknowledged, of murder.

Outside on Abbey Road, an early-evening darkness has descended, as Perrett, Palladin and Mercedes pile into MOJO’s VW Polo in order to hear a CD of unreleased outtakes from the So Alone sessions, including an alternate Give Him A Great Big Kiss, imminently to be released as a picture disc, and a newly discovered full version of the title track. When the CD ends, the car feels suddenly drained of an explosive presence, and both Perrett and Palladin gaze out at the passing streets in silence.

Palladin breaks it, finally. “I really miss him so much – it’s so annoying…”

This article originally appeared in issue 289 of MOJO.

Words: Andrew Perry Images: Getty