Mojo

FEATURE

Quiet Storm

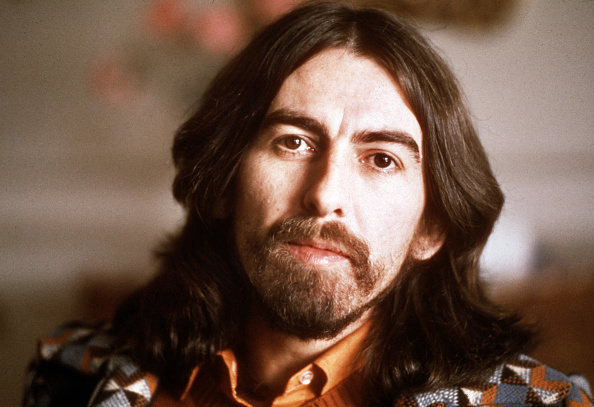

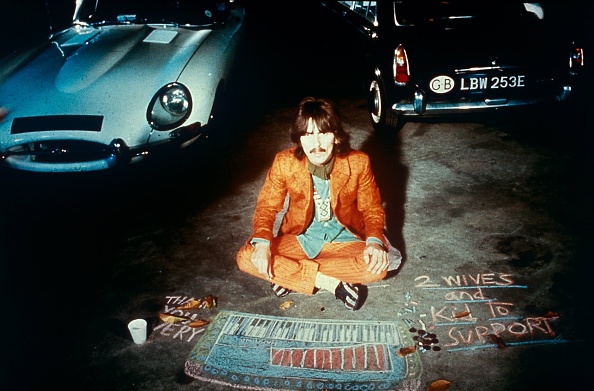

Hare Krishna or hari-kari? George Harrison’s solo years began in a riot of confusion, heartbreak and copyright infringement, noble crusades and genre-bending genius. As his Apple albums re-emerged in a lavish box set in 2014, it was time to boggle at the triumphs and transgressions of The Beatles’ dark horse. “George was a bad boy, believe me.”

Words by Mat Snow

Wonderwall Music: George Harrison

SELDOM WITHOUT A a cigar, Joe Massot looked the part of an American movie big shot. His tales of high adventure and habit of carrying a loaded shooting stick as protection from supposed Cuban assassins made him a cherished ornament of Swinging London.

In 1966 his short film, Reflections On Love, starred Jenny Boyd who, a year later, would co-manage The Beatles’ new Apple Boutique. At the opening on December 5, 1967, Massot charmed George Harrison – married to Jenny’s sister Pattie – into agreeing to provide the soundtrack to a feature he’d just completed. Wonderwall starred Jane Birkin with cameos by Stones girlfriends Anita Pallenberg and Suki Potier and psychedelic designs by The Fool; only Jack MacGowran and Irene Handl stopped the whole thing floating away.

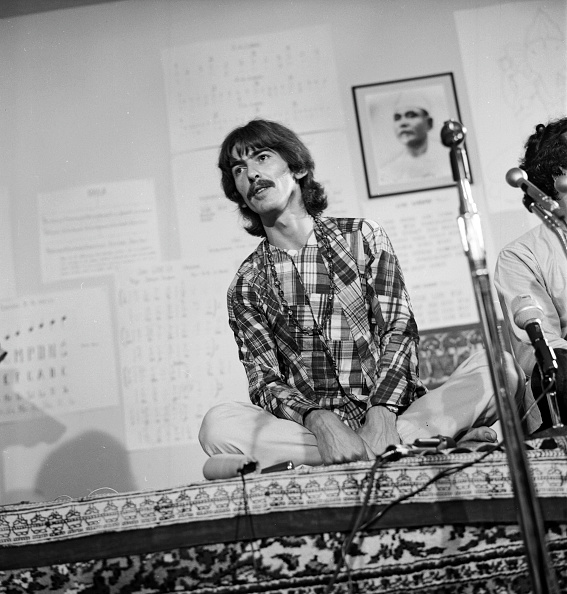

Massot did not exactly have to sell the project to Harrison, who needed an outlet for his stymied musical creativity. Paul McCartney had soundtracked The Family Way the year before, so here was his junior school friend’s chance to keep up. By now a seasoned recording and movie pro, George reviewed the edit with notepad and stopwatch, and planned the music: an East-West fusion along the lines of his friend Ravi Shankar’s score for Jonathan Miller’s 1966 BBC TV production of Alice In Wonderland. Versed in both classical Western and Eastern musics, Shankar’s collaborator was a young music graduate, John Barham. He and George got on, despite The Beatle’s distaste for his beloved Brahms.

“Once in his home in Esher,” Barham recalls, “he slowed down to 16rpm a record of the Brahms Violin Concerto played by David Oistrakh, who I really liked, to complain, ‘Listen to that awful vibrato!’”.

The fruit of their unlikely liaison, Wonderwall Music would provide two firsts: Apple Records’ initial album release and the first credited to George Harrison alone. From this promising start, George’s solo records would veer wildly in style and quality, trailing controversy as well as glory. Nor, despite his Krishna faith and dedication to meditation, would George’s personal life be any more placid. Overcoming his reticence to lead some of rock’s greatest stars to raise funds for disaster victims, life then dealt him a lesson in the world’s cynicism. Then yielding to temptation without a fight, he would lose his marriage and mislay his friends in a hard-partying rock’n’roll soap opera. Yes, George was the Quiet One all right…

ALL WAS TO was to come as 1968 dawned. Back then, Wonderwall offered fresh adventure and musical bonds outside The Beatles. There was a trip to Bombay to record local musicians; Harrison’s friend Eric Clapton attended sessions at Abbey Road. Shankar’s nephew, Aashish Khan, was enthralled when George had him overdub a second sarod part onto the first for the track Love Scene, a studio technique he had never encountered before. Then there were old Merseybeat friends, The Remo Four.

“Colin Manley [Remo Four singer/guitarist] had been at school with George,” explains drummer Roy Dyke. “The Beatles liked The Remo Four as a good band. George wanted some musicians and we were in the right place at the right time.”

George would give Dyke and co a timing and a few musical ideas. “He would say, ‘Can you play a cowboy type thing?’ and so on. It wasn’t like playing with a megastar but with a friend – a relaxed, friendly session. George was telling us about his experiences in India and his experiments in Indian music. Everything was new and interesting.”

The sessions yielded The Remo Four’s amazing, George-produced In The First Place – a lysergic extra lap of the Magical Mystery Tour that didn’t make the original soundtrack album but is restored on the box set version – and The Inner Light, recorded in Bombay as an instrumental but repurposed with George’s overdubbed vocal as his first Beatles B-side, to March ’68’s Lady Madonna. The Inner Light would be George’s last piece of Indian fusion music for decades. That summer he had a crisis of confidence about his efforts in the idiom. “Ravi said to George, ‘I think you should go back to your roots,’” recalls John Barham. “He should take what he wanted from what Ravi had to offer, but be true to his musical origins. Identify himself as a Westerner; don’t take on an alien identity.”

Advice George appeared to take into the troubled sessions for The White Album, from which his While My Guitar Gently Weeps (lead guitar by Clapton) was a highlight. Afterwards, he took off to the US, incorporating a Thanksgiving visit to Bob Dylan at his Bearsville home, where his host was so anxious that his restricted chordal knowledge would be shown up by Harrison’s virtuosity that the guitars stayed unplayed for days. But when they broke them out the result was their beatific co-write, I’d Have You Anytime.

On that trip, George helmed sessions at Sound Recorders in LA for old Mersey compadre Jackie Lomax’s debut Apple album, Is This What You Want? The tracks used Moog 3 synth probings by Bernie Krause, a former member of folk group The Weavers turned paid consultant for the new instrument.

George was intrigued and after the session asked Bernie to put the synthesizer through its paces. According to Krause’s detailed account in his memoir Into A Wild Sanctuary, Harrison had the tape operator record his demonstration without his knowledge or consent. A few months later, in February 1969, he ordered a Moog for Apple, to be escorted through UK customs and set up by Krause. Inviting the latter to his Esher home, Harrison enthusiastically played him a tape of synth music scheduled for release on Apple’s avant-garde sub-label, Zapple.

“It’s my first electronic piece,” George said, “done with a little help from my cats.”

Krause recognised his demonstration piece, edited down to 25 minutes to fit one side of an album. A row ensued, with George seemingly baffled at Krause’s outrage. “If it sells, I’ll send you a couple of quid,” he said, according to Krause. “When Ravi Shankar comes to my house, he’s humble… Trust me. I’m a Beatle.”

Released in May 1969, Electronic Sound didn’t sell, and Krause was never sent so much as a quid. “I didn’t have the money or energy to sue,” he wrote. Today an eminent soundscape recordist and bio-acoustician, he tells MOJO, “I stand by the explanation of my experience as written.” And asked if the label has offered any payment in relation to the current reissue, he replies: “Not a sou. Not a pittance. Not a ha’penny. Nada, rien.”

“Ravi said to George, ‘I think you should go back to your roots – don’t take on an alien identity.”

John Barham

MEANWHILE, BACK AT the day job, Harrison’s reputation had never been higher, with Here Comes The Sun and Something the acclaimed peaks of The Beatles’ climactic Abbey Road album. Yet now he finally had the spotlight, George sought the shade of a new set of outsize musical personalities.

When Eric Clapton’s band Blind Faith toured the US in 1969, among their support acts were Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, a blue-eyed rock’n’soul revue fronted by husband-and-wife singer-songwriters Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett. They so appealed to Clapton that, losing interest in his own group, he would join them playing guitar on-stage. When Delaney & Bonnie toured Europe, Clapton stayed and, inspired to join in the fun as a humble sideman, Harrison overcame his distaste for the stage. “Would you mind if I joined the band?” he asked Delaney. “Would there be too many guitars?”

Picking up George at Kinfauns, his Esher bungalow, on the morning of December 2, 1969, the tour set off for the next date in Bristol. In the party was gospel-soul singer-organist Billy Preston, a contributor to The Beatles’ Get Back, Something and I Want You (She’s So Heavy). George loved The Edwin Hawkins Singers’ summer ’69 hit Oh Happy Day and asked Billy and Delaney how to write in that vein.

Like Imagine for John Lennon, My Sweet Lord would condense George’s idealism into an enduring worldwide anthem: his greatest, yet, it would transpire, most burdensome hit. Among a backlog of tunes dating back to 1966 including The Art Of Dying and Isn’t It A Pity, it was one of several new songs George brought to Abbey Road in spring 1970. They would pour into a triple album whose expansiveness, tunefulness and optimism filled the black hole left by The Beatles, whose split went public on April 10.

“I heard many of the songs that would appear on All Things Must Pass when George invited me to dinner,” recalls John Barham of a Saturday evening with the Harrisons at Friar Park, their vast new home in Henley-on-Thames. “Later we went through the arrangements together in one of the rooms with a piano. George played me some Phil Spector productions, including Proud Mary [by Checkmates Ltd],” Barham continues. “We were very impressed – I’d never heard a sound like that before, and that was the kind George wanted.”

Endearing himself to Harrison through his post-production work salvaging The Beatles’ final album Let It Be, Spector would now be working with a seasoned songsmith at Abbey Road rather than at Gold Star Studios with the puppets of his early ’60s heyday. Yet his approach to recording had not changed: a Wall of Sound.

“The way that symphony orchestras and choirs had been for hundreds of years, the studio was laid out for a rock orchestra, the guitarists and keyboardists regimented in rows,” says Barham.

Among the keyboardists was former Delaney & Bonnie sideman (and soon to be a Domino with Eric ‘Derek’ Clapton), Bobby Whitlock: “When you walked into this massive room, you’d see two sets of drums on risers, a piano, organ and other electric keyboards to the wall on the left, up against the far wall on the right were Badfinger, and in the centre were George and Eric and the guitars. Everybody played at once.”

“George made everybody feel at home,” remembers bassist and old friend from Hamburg, Klaus Voormann. “In the studio he made a little altar with his joss sticks and little figures; everyone felt good.”

Spector took the cymbals off the drum kits, as he had done for Lennon’s Instant Karma, and removed the buffers from between the amplifiers to enable leakage.

“When we recorded Wah-Wah, the sound in your headphones was reasonably dry, but in the control room to hear the playback, the sound was loud and incredible,” remembers Voormann.

“I loved it but George didn’t: ‘What are you doing to my song?’”

When George’s mother died suddenly that July, sessions were suspended. Progress further slowed as he insisted upon retake after retake of small vocal and instrumental details. Behind the scenes, meanwhile, Eric Clapton had fallen in love with the neglected Pattie, threatening to lose himself in heroin if she didn’t run off with him.

“I went down that road of smack with Eric, which started during the recording of All Things in the Abbey Road tea room,” recalls Bobby Whitlock. “This African conga player who played with Stevie Winwood and used to supply everybody brought it – Reebop [Kwaku Baah, who died in 1983].”

And then there was My Sweet Lord. “Listening to the playback of My Sweet Lord in the control room at EMI,” says Whitlock, “I innocently brought up, Man, that’s just like He’s So Fine [the 1962 Chiffons’ hit]. Whoah! A hush all over the room. George said, ‘I’ll take care of it if it ever comes around.’”

Klaus Voormann: “George was laughing, ‘I didn’t know!’ I don’t think he realised the trouble he could get into if he released it; I think he thought that you’d just pay some money.”

The chart-topping single that heralded All Things Must Pass (an unprecedented worldwide Number 1 triple LP), My Sweet Lord was a hit immediately slapped with a writ by Bright Tunes, which controlled the copyright of He’s So Fine. The copyright case would drag on for 20 years. But worse was to come.

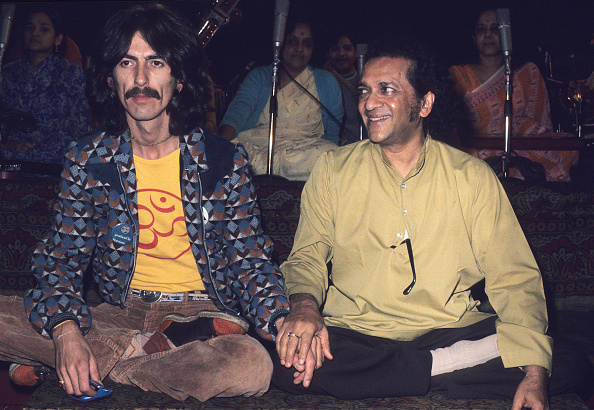

Got My Mind Set On You: George Harrison sits with Ravi Shankar in 1974 in London, England.

A FORTNIGHT BEOFRE the release of All Things Must Pass, in November 1970 a tropical cyclone struck the Ganges Delta; some half-a-million people died. Civil war then added manmade to natural disaster. To help his fellow Bengalis, Ravi Shankar enlisted his superstar friend. As well as recording the charity chart-topper, Bangla Desh, George organised the first ever all-star rock’n’roll benefit concert, featuring Bob Dylan’s live US comeback, on Sunday, August 1, 1971, at New York’s Madison Square Garden, with a spin-off album and movie.

The triumph had a bitter aftermath. Record companies and retail creamed off vast profits, while Harrison’s manager Allen Klein failed to claim charitable status on the income. In the UK alone George had to write a personal cheque for a million pounds as tax on income he’d donated straight to charity.

“George told me later that the way the money disappeared was brutal,” recalls Neil Innes of The Bonzo Dog Band. “To naively set out with such a good cause and discover that humanity is horrible and the world a rough neighbourhood when there are large sums of money around hurt George a lot.”

Harrison withdrew and would do little but mutter his mantra “Gopala Krishna, Om Hari Om…” for comfort. Eventually, the songs for Living In The Material World would emerge, from Sue Me, Sue You Blues to the visionary The Day The World Gets ’Round. With renewed creativity, darkness lifted. Drummer Jim Keltner had befriended George on Lennon’s Imagine sessions and worked on Harrison’s new album: “During the Material World sessions, George’s hair was long, thick and shiny, his skin and eyes were clear. He wasn’t smoking and he had the beads. And always at Friar Park the smell of incense wafting from somewhere. He would sit down with his guitar and play his song for you. That’s just how John and Bob Dylan would do it too – the classic singer-songwriter approach.”

Much of the recording took place at Friar Park, with Keltner, Voormann, Spooky Tooth keyboard player Gary Wright and pianist-by-appointment Nicky Hopkins. “It was an intimate, quiet, friendly atmosphere,” reflects Voormann, “a big difference from Imagine with John in Ascot and film cameras leaning over our shoulders and Yoko interrupting the sessions for a song like Jealous Guy screaming that [self-styled black revolutionary] Michael X was on the phone. George would never have allowed anything like that.”

Some interruptions, however, were tolerated…

“On Be Here Now I played upright bass in the toilet to get a nice sound. As I was playing [veteran Beatles driver/minder] Mal Evans came in and flushed it. George would laugh. I did not know Oasis used the same title. George hated them: ‘Fucking Oasis – can’t stand them!’”

John Barham has less happy memories: “I began to sense a dark atmosphere around Friar Park. George was getting moody and introverted. Something was upsetting him. It didn’t feel very good to be around him. My instinct was to stay away. I didn’t see George again for 17 years.”

A friend to both George and Pattie, Harrison’s PA Chris O’Dell recalls “a darkness to do with their relationship. Pattie simply was not going in the same direction that George was, with his meditation and spiritual life.” Contrastingly, cocaine and booze weren’t helping, with a low point when George announced to a stunned Ringo that he was in love with his wife, Maureen.

“Maureen and Ringo had their own problems before things started with George,” says O’Dell. “Neither George nor Maureen ever said of their relationship that it became physical though I definitely witnessed a deep attraction. Women threw themselves at George.”

Harrison, meanwhile, threw himself into work. Itching to leave EMI/Capitol and the increasingly moribund Apple label, he planned a new record deal and his own label, Dark Horse. He produced its first two album releases: Ravi Shankar’s Shankar Family & Friends, and the South Shields soft-rock duo Splinter’s The Place I Love. Dark Horse’s distributor, A&M, hired the super-efficient and attractive Olivia Arias as George’s secretary. With Pattie finally having left George for Eric Clapton in July 1974, romance was only a matter of time.

“Wah Wah sounded loud and incredible. I loved it but George didn’t: ‘What are you doing to my song?’”

Klaus Voormann

A US NUMBER 1 album, Living In The Material World had knocked Paul McCartney’s Red Rose Speedway off the summit and spawned the sprightly but lightweight Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth), a Stateside chart-topper again at Paul’s expense (My Love). But George could not match Paul for productivity and the self-imposed pressure was on. Getting Dark Horse Records and its artists off to a flying start had drained him and left little time to make his own music. Worse, he had given himself a deadline by agreeing to a full North American tour, teamed with Ravi Shankar and scheduled for November/December.

In songs destined for his fifth solo album, George responded to the end of his marriage both conventionally, in So Sad, and sourly, in his rewrite of The Everly Brothers’ Bye Bye Love (“There goes our lady/With a you-know-who/I know she’s happy/And old Clapper too”). New to the musicianly mix was Sly Stone drummer Andy Newmark, who’d bumped into the Beatle at Ronnie Wood’s Richmond pad: “Willie [Weeks, bassist] and I came down to the kitchen and there was George drinking a cup of tea. Wow! He looked just like in all the pictures.”

Invited with Weeks to Friar Park to play on what was to become Dark Horse, Newmark found Harrison “a very relaxed, easy-going, non-assertive band-leader. George brought in people he knew had the musical instincts to play his songs the way he wanted so he didn’t have to be too specific in his direction. He let us do our thing.”

Talent-spotted by George with Tom Scott’s LA Express backing Joni Mitchell live in London, young guitarist Robben Ford was also invited to Friar Park. “We went up at about 1pm and Pattie made tea while we waited because George got up around four. She had the loveliest personality, like an angel. When George showed up they didn’t interact and she just disappeared. At one in the morning we started recording and cut two songs – Simply Shady and Hari’s On Tour – then returned to London to resume the tour with Joni.”

George finished the album in LA and rehearsed the touring band there, but the schedule was too much for his voice, shot from laryngitis, abuse and overwork. Though propped up on-stage by Billy Preston’s energy and good humour, Harrison was not a commanding front man over those seven weeks on the road with Shankar. Dubbing it the ‘Dark Hoarse Tour’, critics were not kind.

Chris O’Dell was tour manager: “The success of the Bangladesh event allowed him to think he would enjoy a huge tour. And then musicians like CSNY would say how much money they made with Bill Graham as promoter. Much as George loved Ravi, by the time he got on stage he could tell that people were bored, and if he couldn’t sing as well, he was having a hard time.”

Robben Ford: “When we went out there the audience would go nuts, then it would get dull. The audience area was full of smoke and both on-stage and off-stage there was a tremendous amount of coke, weed, and booze. It affected everything.”

Andy Newmark: “I had never toured on that level with private jets, five star hotels, your luggage being collected. You were part of a giant machine. George was very approachable and down to earth. But lingering in the background were the facts that he’d lost his voice, his marriage had ended, and he was clearly under stress, struggling to keep it all going. We all wanted to make him feel supported.”

As well as his marriage, George’s ’70s honeymoon with the public was over. “Olivia came into the picture at just the right time, a crazy, dark time,” says Jim Keltner. “She is a strong person, and when he fell for her we all agreed that was a good thing. It wasn’t good for him to be on his own, and without her things would have got worse.”

“He’d lost his voice, his marriage had ended, and he was clearly struggling to keep it all going.”

Andy Newmark

My Sweet Lord: Guitarist George Harrison poses for a portrait with Indian sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar in circa 1975.

THEY DIDN’T IMPROVE at once. Dark Horse had been a relative disappointment. Fulfilling his expiring Apple contract, could the next album, Extra Texture (Read All About It), restore his fortunes? When Splinter pulled out of sessions booked at A&M’s LA studios due to illness, George took them. “Where on previous records George was living at home in Friar Park, in LA he was staying in a hotel and he was a big deal,” says Keltner. “Too many people wanted to get to him, too many bad things were available. He should never have made a record outside Friar Park.”

Klaus Voormann agrees: “In LA I was not happy about the way George was developing, and I think he felt embarrassed about that. When they do too much cocaine, people lose their reliability. They turn vicious. It was not the old George.”

Today a record industry kingpin and producer of some of pop’s biggest stars, keyboardist David Foster was in his apartment when he got the call. He was overjoyed, but the scene in the studio was sobering: “We would be playing with the piano facing the wall for soundproof reasons, so I couldn’t see any of the other musicians. The bass would drop out, then the drums, then the guitar, so I thought maybe this is where I should play a solo. I was so young and naive I didn’t realise they were leaving the room – to do whatever they were doing.”

The final solo album of the Apple era is a mixed bag, perhaps the best song a sincere synth-soul tribute to Motown singer-songwriter Smokey Robinson, Ooh Baby (You Know That I Love You). At the end, His Name Is Legs (Ladies And Gentlemen) features the japes of George’s Bonzos pal ‘Legs’ Larry Smith.

“One night he invited me over to dinner and said he had a little surprise for me,” Smith remembers. “In the main hall there was a Steinway grand piano, and he burst in, sat down, gave me a little nod, and started playing this song. Jesus Christ, I realised, it’s about me! I sang the chorus, and did my overdubs one crazy night. I was greatly touched by the whole thing.”

Larry’s fellow Bonzo, Neil Innes, had teamed with Monty Python’s Eric Idle on a new BBC2 comedy, Rutland Weekend Television, and Python fan Harrison was drawn into their orbit.

“Pattie had left George for Eric Clapton, and while the Pythons were playing Drury Lane, Eric Idle’s wife left as well,” Innes recalls. “So the two victims of love became bosom pals.”

One of Innes’s ideas was a spoof of The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night. It all tied in when George appeared on the RWT Christmas special on Boxing Day, 1975. “He’d already met the [Rutles prefiguring] band, Fatso, and we did drink rather a lot of Dom Perignon which he brought,” says Innes. “Eric Clapton was envious of the Bonzos because we could muck about, and always said he wished he could go on stage with a parrot on his shoulder. George beat him to it.”

It was George all over: unpredictable. Who guessed he would produce a solo album that would outdo John or Paul? Or overcome his distaste for the spotlight to lead his fellow superstars in a stand on behalf of the world’s starving? And who would have tipped the po-faced former Fab to turn his talent to laughter? “After The Beatles, Monty Python was my favourite thing,” he explained. “They were the only ones who could see that everything was a big joke.”

As they migrated from the small to the big screen, Python became George’s new team where he could resume his role as the Quiet One – behind the scenes, as a movie producer. Making records slipped down his priorities, yet there were musical successes to come. He and Olivia married and Dhani was born. George’s dark age was over.

This article originally appeared in issue 258 of MOJO.

Words: Andrew Perry Images: Getty