Mojo

FEATURE

A farewell to London

Billie Holiday’s last official London gig was on 14th February, 1954 at the Flamingo Club. Fred Dellar remembers a magical evening.

Words by Andrew Perry

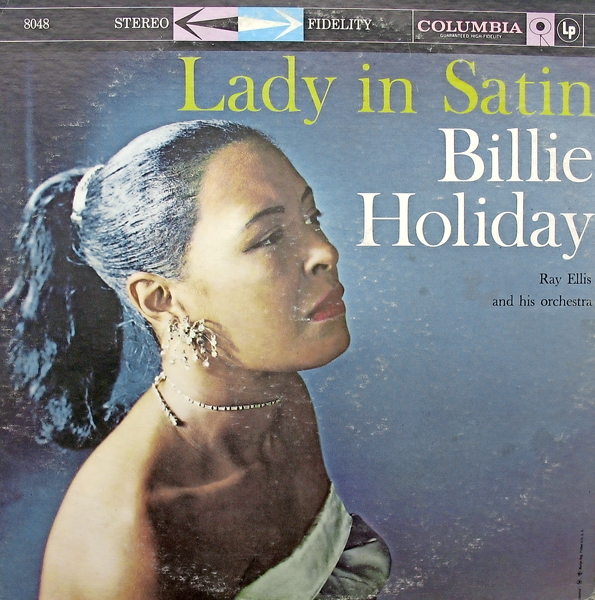

Billie Holiday records her penultimate album ‘Lady in Satin’ at the Columbia Records studio in December 1957.

Vocalion. I loved that label. In the era of 78 rpm shellac singles, Vocalion both caught the eye and captured jazz hearts. It looked regal and it was regal. No doubt about that. For it featured early releases by Billie Holiday. I was just a kid, hardly into my teens. I couldn’t afford to buy new records. I scoured junk-piles, accumulating a jazz collection for a few pence at a time. Hearing Billie’s lemon-edged voice, effortlessly swinging, yet heart-searing on ballads, was a fantastic reward for spending time in rat-infested junkyards. I never fell out of love with her. Never.

Fast forward to early 1954. I was 23 then, a factory worker who had survived two years in the RAF and come out the other side, still jazz-crazy. The news on the grapevine was that Billie Holiday was to play a club gig at The Flamingo, in the Mapleton Restaurant, just off Leicester Square, after her appearance with the Jack Parnell band at the Royal Albert Hall.

The Flamingo was London’s jazz Valhalla, launched by Jeff Kruger in August 1952. On the first day, a 400-strong queue formed early for the opening. A squad of police was drafted in to keep order before the first band appeared, four hours later. There’d been trouble there initially. But it was soon sorted out. Kruger’s father had been East End gangster Jack Spot’s barber. When a number of handbag thefts threatened the club, some friendly villains sorted things out.

“The local Charing Cross hospital had a spate of broken fingers to heal,” Kruger would later confide to me.

“No artist in the world would have wanted to follow Billie Holiday on the stage that night,”

It was on St Valentine’s Day, Sunday, February 14, 1954 that my girlfriend Pam and I caught the tube to Leicester Square and headed into the Flamingo. It was overcrowded from the start. It seemed that every jazz musician in London was in the place.

“Look, there’s Ray Ellington over there,” observed Pam as we waited for Billie to arrive from the Albert. At ten o’clock we were still waiting. Eventually and unbelievably, it happened.

Billie Holiday was on-stage. Her pianist Carl Drinkard played a lead-in, the club’s regular rhythm section – drummer Tony Kinsey plus bassist Sammy Stokes – moved into action and Billie was suddenly in incomparable flight. I can’t recall what she sang that night, just that she was there. I somehow clambered onto a chair and two girls (neither of which was Pam) clung on to either side of me. Sax-player Don Weller, whom Billie had invited to the Flamingo, tried desperately to reach the stage but was unable to make his way through the crowd and settled for a later drink with Billie in the band room. Somewhere, Jeff Kruger was smiling in the background.

“Everyone warned me that Billie was a drug addict but her manager, Joe Glaser, swore to me that she was clean,” Kruger mused later. “‘However,’ said Glaser, ‘She’s a kind of nervous lady and prone to take a drink. That’s the stuff you gotta watch.’”

Billie had played concerts in Manchester and Nottingham, prior to her two London dates. En route to the first show – at Manchester – Billie took a comfort stop at a transport cafe. “When she came out of the Ladies to rejoin us,” remembered Kruger, “she was staggering. She’d been drinking. But where was she getting it from? She didn’t even take her handbag in with her. She had no drinks in her purse or travelling bag. However, she did carry an inordinate number of small perfume bottles and it was in these that we found her drink.”

Ben Webster, Billie Holiday and Johnny Russell in 1935.

Billie had enjoyed a whisky or two prior to her set at the Flamingo and was singing as though inspired. Time has dimmed my memory of everything except that she was superb. Jack Parnell, the drummer who’d led the big band at the Albert Hall recalls that while Billie looked like a sack of old clothes at rehearsals, by the end of the evening she looked like a girl of 18.

“She was thrilled that we had given her a suite at a hotel,” said Jeff Kruger. “She was used to being shoved into third-rate rooms on the road. At Manchester, her [future] husband, the brutish [Louis] McKay was there, a man who had endearing habits like hitting his wife when the mood took him. When she needed him, more often than not he’d be out spending her money, usually on seducing other women. Little wonder that Billie turned to drink for consolation. Indeed, as I looked past McKay, I could see she was already out of her skull. Her slurred words came through a fog of alcohol.”

“Listen honey,” Billie told Kruger, “when it’s show time, you just take me out to that microphone. Put my left hand on the mike, open the curtain and I’ll go. When you want me to finish, after an hour or whatever, just shut the curtains and come and get me. I won’t disgrace you.”

Billie was as good as her word. “She did 50 minutes,” said Kruger, “sang like a bird, never missed a note – though she was roaring drunk.”

At the Flamingo, she turned on the magic yet again. “No artist in the world would have wanted to follow Billie Holiday on the stage that night,” said Kruger. Respected jazz critic Max Jones added that, “those present were fortunate to hear Lady Day at her exquisite best.”

As one of those fortunate souls and a Billie-believer of long standing, I can only concur. There are moments in life when something happens, moments so magical you know they can never, never be repeated. That night at the Flamingo, at the conclusion of her only British tour, Billie Holiday delivered such a moment.

Lady Sings The Blues

From joyful pop to agony and heartbreak, a life live in 10 songs…

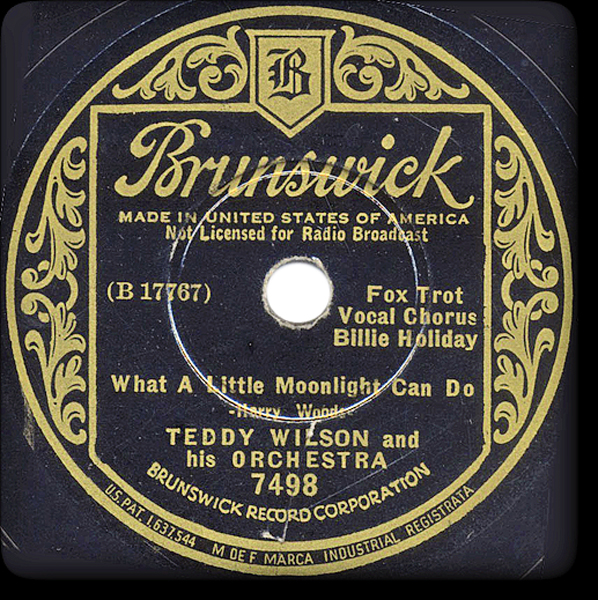

1 What A Little Moonlight Can Do

(Brunswick, 1935)

Not Billie’s debut recording – she’d recorded Riffin’ The Scotch with Benny Goodman in 1933 – this nevertheless was a joyous high-point in a session of four songs that really launched the New York-based singer’s on-disc career. Credited to The Teddy Wilson Orchestra, a small, all-star group featuring pianist Wilson, Benny Goodman on clarinet, Roy Eldridge on trumpet, John Kirby on bass, John Trueheart on guitar and drummer Cozy Cole, this was just a pop song of the moment, stemming from the British film Roadhouse and aimed at the burgeoning jukebox trade by producer John Hammond. But the 20-year-old Billie, small-voiced, less intense than later, was already phrasing in an inimitable and unique fashion, and transformed the number into a memorable standard, one that would still form part of her performances many years later. FD

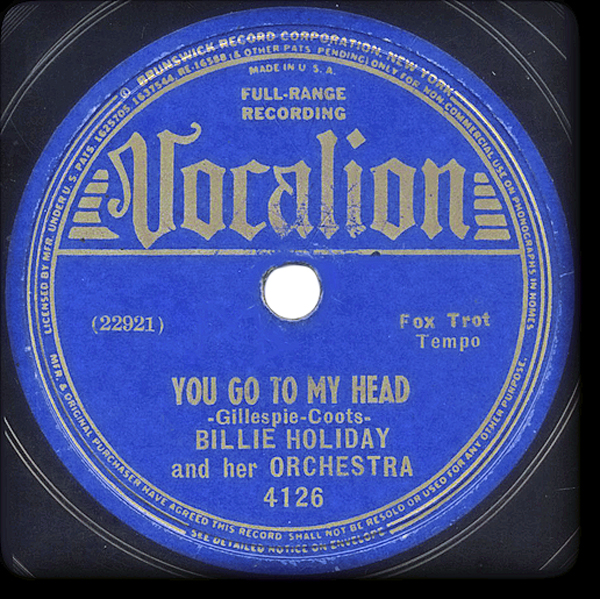

2 You Go To My Head

(Vocalion, 1938)

On May 11, 1938, Billie Holiday took a day off from touring with the Artie Shaw band to record this J Fred Coots and Haven Gillespie torch ballad with a six-piece pick-up band in New York. Her previous collaborator, Teddy Wilson, had already enjoyed a hit with Nan Wynn on their refined take; Billie would return with a more considered version under Norman Granz in 1952. Here though, she’s abandoned to the thrill of the moment, living the narcotic rush of cursed love through her woozy slur. Cushioned by lazily eloquent horns and strolling piano, her elongation of the title refrain conveys joy, hope, pain, self-doubt. The effect is dizzying and yields the second of three Top 20 hits for her that year. LW

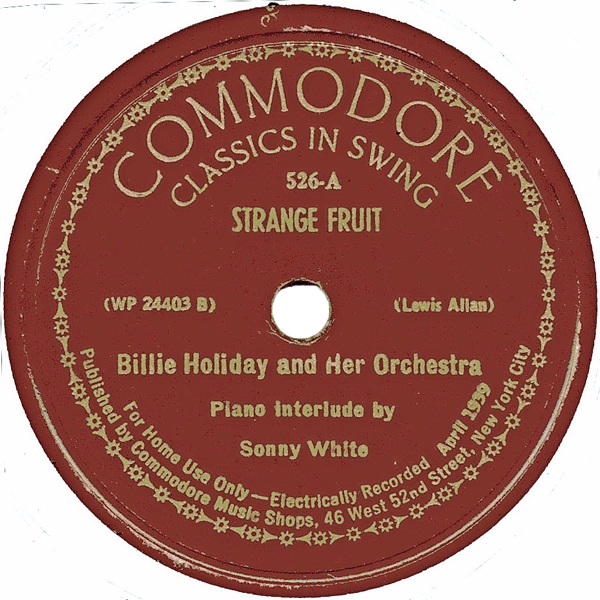

3 Strange Fruit

(Commodore, 1939)

Nothing like it ever. Haunts everyone who hears it. Haunted her the rest of her life. Communist teacher Abel Meeropol’s lynching song came for her when she was 23 – a vibrant blue-jazz chantoozie who knew her every minute happened because-she-was-black. She’d never said it. The song said it. She sang it. For little Commodore because John Hammond and Columbia couldn’t face it. The Café Society band’s long mood-set found the heart; muted trumpet then piano just remembering for a while and, after 70 seconds, Billie… telling it. No histrionics despite the terror, just her honey voice dripping thick blood from every curdled syllable. “Pastoral scene… bulging eyes… twisted mouth… burning flesh… rot… here is a strange and bitter crop”. See also the live video of 1959, shortly before she died – still all haunt. PS

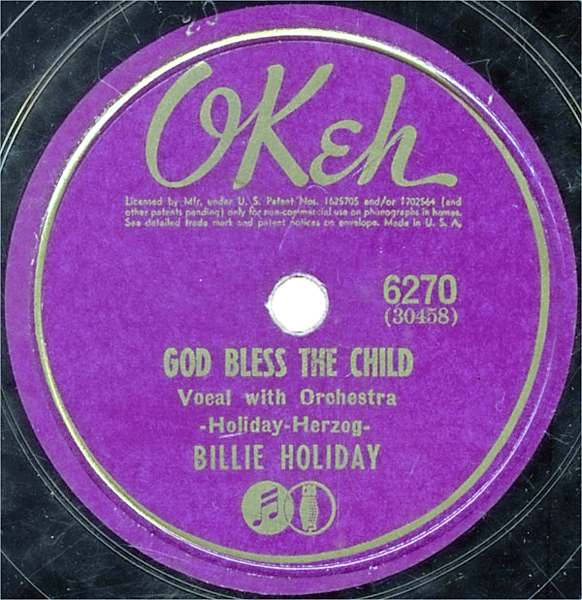

4 God Bless the Child

(Okeh, 1941)

Billie’s fractious relationship with her mother reached breaking point when the older woman refused to lend her daughter money, despite being the regular recipient of Billie’s post-success generosity. This frustrating situation fed into God Bless The Child, a jumbled piece of homespun philosophy about independence, survival of the fittest, the transient nature of money and the limitations of family ties. The song’s gentle wisdom produced one of Billie’s most touching performances and lauded compositions; except, she probably didn’t write it. Co-writer Arthur Herzog remembers asking Billie for a down-home Southern expression around which to build a song. Using some of her melodic suggestions, Herzog said, “Billie, I’ll give you half the song if you make the record.” CI

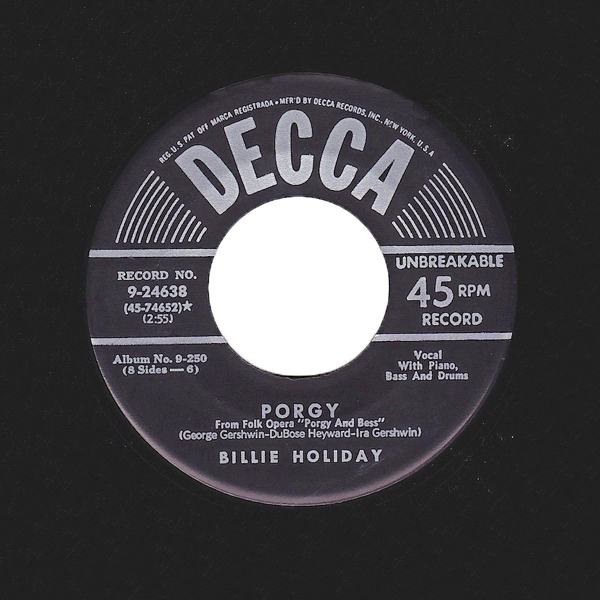

5 Porgy

(Decca, 1948)

By the ’40s Decca had become one of the foremost labels in America, buoyed by multimillion releases from Bing Crosby, The Andrews Sisters, etc. Signing for the label in 1944 should have revived Billie’s recording career – but in the wake of 1945’s Lover Man her hits dried up, possibly due to lack of airplay caused by her increasingly bad reputation. Even so, her material from this period was of high quality, beautifully produced, and often featuring top arrangers like Gordon Jenkins or Toots Camarata. Porgy was an unlikely vehicle. Originally titled I Loves You, Porgy and a duet from George Gershwin’s Porgy And Bess, Billie delivering the song in soft, resigned manner, with intimate backing from pianist Bobby Tucker’s trio. Nina Simone said the interpretation was the reason she first loved Billie Holiday. FD

6 My Sweet Hunk O’ Trash

(Decca, 1949)

Adolescent Billie earned cash by cleaning brothel stoops (and the wallets of unsuspecting johns) in Baltimore. One ‘house’ had a gramophone and she would spin 78s by her Jazz Age heroes: Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong. “I copied my style from Louis,” she later noted. “I heard a record [he] made called West End Blues. He doesn’t say any words and I thought, this is wonderful!” In 1947 she took a mostly-singing role in the Louis film New Orleans. After a year in prison for one of several dope busts, she recorded her only session with Satch in 1949, including this tongue-in-cheek sass contest, showing the wild wit of a torch singer known for gloomy Sundays. Controversially, Armstrong allegedly says, “Fuck ’em, baby” at 2:53. A re-record was ordered, but what sounds like the original is still available. MS

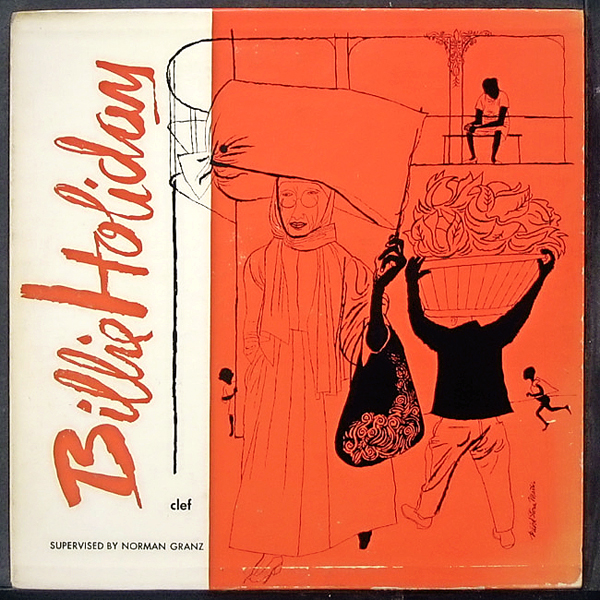

7 Love For Sale

(Clef/Verve, 1954)

Recorded late April, 1952, probably during her first session for Norman Granz, Love For Sale overtured Billie’s final tragedy – correct usage: Aristotle would have acknowledged the “pity and awe” as she sang for everybody and hit the skids, her power unvanquished except by death. The track declares her ’40s ‘pop’ period over, setting her slur-and-veer vocal against a lone piano – Oscar Peterson playing with a near-classical formality, which works by ignoring her. Cole Porter wrote the song; Billie lived it as a teenage hooker. But she keeps her cool, her self-possession, to insinuate the brutal truths she knows: “Appetising young love for sale/Love that’s fresh and still unspoiled/Love that’s only slightly soiled…” PS

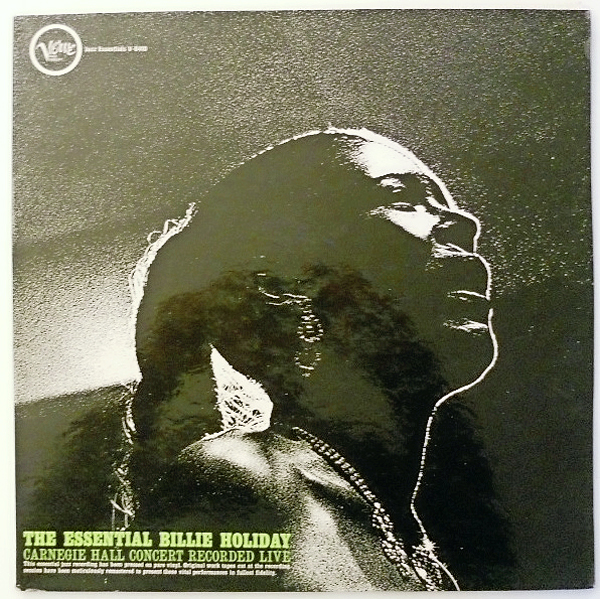

8 Don’t Explain

(Verve, 1957)

Like another Holiday favourite, My Man, Don’t Explain has a disturbing power. Co-authored by Billie with Arthur Herzog, the song is a moving portrayal of the kind of emotional dependency which Billie often suffered from (“You’re my joy and pain,” she sings, helplessly, “I’m so completely yours”) and exudes a poignant, painful authenticity. Though ostensibly inspired by husband Jimmy Monroe’s infidelities, the song’s acceptance of betrayal also speaks of Billie’s life-long attitude to romance. The 1945 recording with Toots Camarata’s lush strings underlines Billie’s vulnerability, but the starker 1957 Carnegie Hall version at a book-promoting concert designed to underline the autobiographical aspects of her music finds the singer at her most vivid and emotionally revealed. CI

9 Fine and Mellow

(The Sound Of Jazz TV show, 1957)

The producers of this TV special captured various performances with integrity and minimal pretension – qualities Holiday owned for a lifetime. In her segment, she sang her composition Fine And Mellow, a straight blues and setlist regular. Joining her was a jazz super-session: Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge and others. But her true co-star was old pal, fellow Count Basie alumnus and tenor legend Lester Young. He’d named her Lady Day, she’d dubbed him Prez – for President. Although sick with alcoholism, when Prez – the only horn-man seated – stood to solo he blew a chorus that wafted like a low, sad moan over the studio. Lady gave with a knowing, high-beam smile, as the crew in the control room quietly wept. MS

10 I’m A Fool To Want You

(Columbia, 1958)

February 20, 1958, with arranger/conductor Ray Ellis, a 40-piece orchestra and a water pitcher of vodka, Billie Holiday stares into the abyss on a cover of the Sinatra song which becomes the opening track on Lady In Satin, her penultimate album. Her trebly quaver, vitiated from years of abuse and mainlined to her soul, captures the agony and loneliness of a life of unrequited love, in its resigned, broken tone. Framed by muted horns and strings that rise then fall then rise again – as if atuned to her papery breathing – the depth of emotion and self-knowledge are palpable when she whisper-croaks, “Take me back, I love you.” In just 17 months’ time she’ll be gone. LW

Compiled and written by Fred Dellar, Chris Ingham, Michael Simmons, Phil Sutcliffe and Lois Wilson

These articles originally appeared in issue 259 of MOJO

Images: Getty