Q

GOLD

Three Imaginary Boys

How did a trio of bong-huffing street rats from Northern California end up selling over 40 million albums of “honest” punk rock and remain best pals for five decades? In early 2020 – on the 30th anniversary of their debut and just before the arrival of Green Day’s 13th album – Dave Everley joined Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt and Tré Cool on the road to discover exactly how they managed it.

Words by Dave Everley

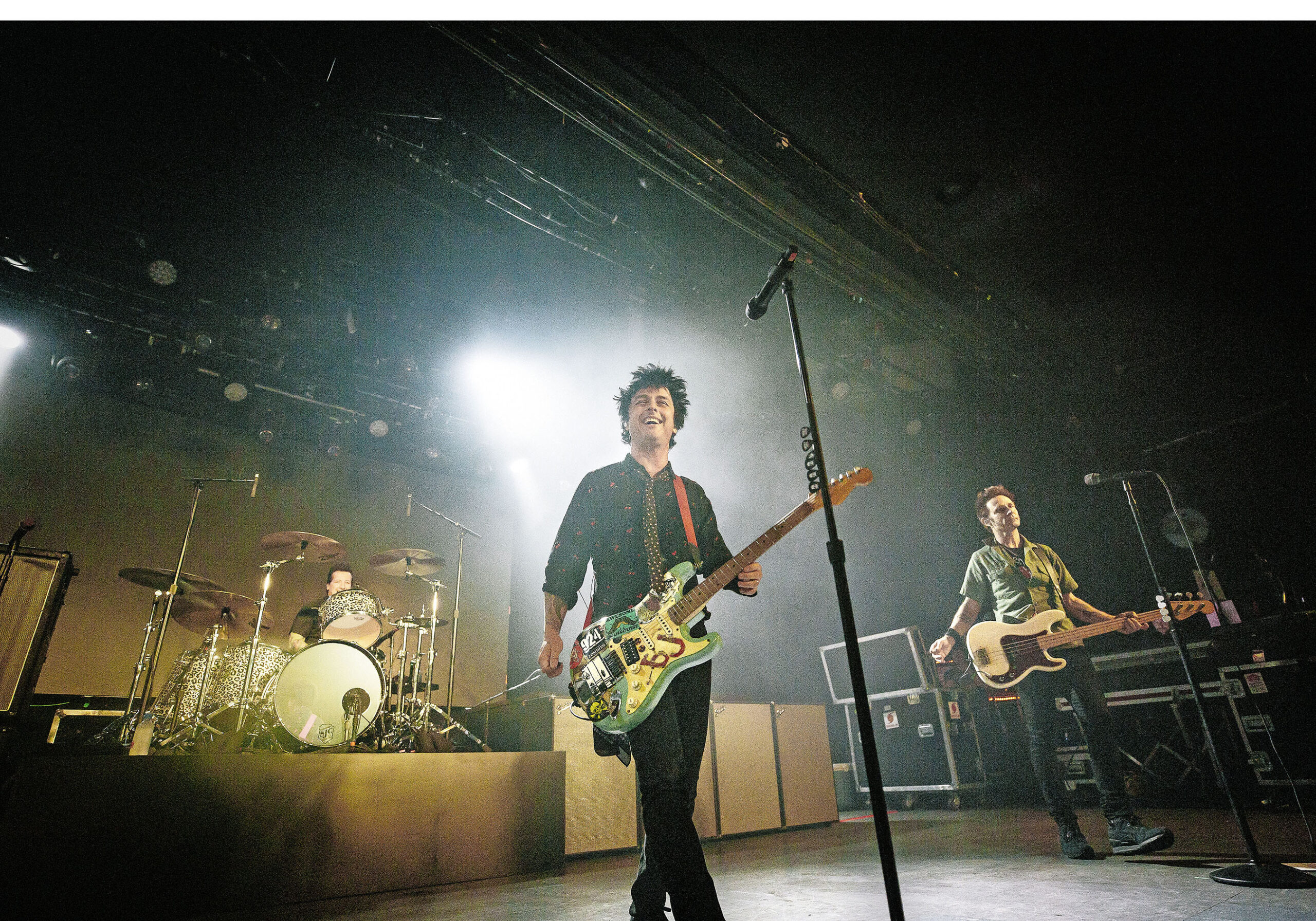

Sharp-dressed men: Mike Dirnt (left), Billie Joe Armstrong and Tré Cool.

Billie Joe Armstrong doesn’t want to talk about you-know-who, but there’s no way around it. It’s 13 December 2019, and we’re speaking a couple of hours after the US House Judiciary Committee approved two articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump. The grinding wheels of justice have been set in motion for the next stage in a process that could culminate in an historic decision.

Except Armstrong isn’t so sure. He’s been keeping an eye on how things are playing out, and he’s not feeling confident about the eventual outcome.

“Oh man, I don’t know if it looks so good,” he says. “The last word is going to come from the Senate, and they’re controlled by the Republican Party, the most dangerous political organisation in the world. And they’re going to acquit him.” He sighs. “They’ve declared war on liberals. Our country is heading towards civil war. It’s just fucking exhausting and depressing.”

There’s another reason why the Commander-in-Chief of the United States is an unavoidable topic when talking to Armstrong. Trump casts a puffed-up shadow over Green Day’s new album, officially titled Father Of All… but, according to the singer, really called Father Of All Motherfuckers.

Armstrong attempts to suggest that the phrase “Father Of All Motherfuckers” refers to himself, but he’s fooling no one. He concedes that one man’s name was the first that sprang to mind when he initially plucked it out of the air and scribbled it down. “Father of all Motherfuckers” might as well be Donald Trump’s Twitter bio.

“The way I look at it, he’s like this racist Yelp review of America,” says Armstrong. “Just shooting his mouth off, saying shit. The man must get up and look in a mirror and see Brad Pitt looking back at him. It doesn’t register that he’s a piece of shit. That’s the definition of narcissism.”

Green Day have been here before, 16 years ago. Back then the man in their crosshairs was George W Bush, and the weapon in their hands was American Idiot, arguably the defining protest album of the era and certainly the biggest. But this time around, says Armstrong, it’s different.

“It’s worse,” he says despondently. “It’s not even sad, it’s frightening. We’re dipping our toes into fascism. I wake up every day and go, ‘What the fuck is going to happen today?’”

What’s a multi-million-selling punk rock lifer to do? If you’re Billie Joe Armstrong, you make a 26-minute party record to soundtrack the end of history.

Green Day are America’s high school band, and have been since they gatecrashed the stage on prom night in 1994, drunk and gurning and refusing to leave.

Between then and now, they’ve cycled through juvenilia, agitation, sedition, self-destruction and redemption. They’ve teetered on the edge of irrelevance more than once, but managed to pull themselves back each time via a combination of self-belief, stubbornness and an unexpected, if accidental ability to reach beyond genre boundaries.

“It’s honest music,” is Mike Dirnt’s explanation. The bassist is a rock’n’roll fundamentalist with a terrier’s physique and a hangdog face. “Making honest music, and good music, is hard. Anyone can write three chords and some lies.”

For all their punk rock credentials, interviewing Green Day is an inflexible operation. Time with them is metered to the minute: an hour with Armstrong, Dirnt and Muppet-voiced drummer Tré Cool in a hotel room in Madrid, and a 30-minute phone call a few weeks later with Billie Joe. No more, no less.

This is partly due to the demands of time. Green Day are in Spain on a tight schedule. They’re due to open the MTV VMAs and play a show of their own at tiny (for them) 2000-capacity club in Madrid. The latter will see them run through their career-making 1994 album Dookie, a record with a longer tail than most other Gen X-era blockbusters.

It’s partly also down to the fact that Green Day are a gang, in the rock’n’roll sense of the term. Two junior school buddies (Armstrong and Dirnt) and a third they met in their mid-teens (Cool), they keep the circle around themselves tight. It works as a defence mechanism, but it’s even more elemental than that. “We’re a teenage rock’n’roll band in our mid-40s,” says a black-clad Armstrong, sitting in the centre of an arc of chairs in the band’s Spanish hotel suite, Cool and Dirnt either side of him. “And that feels great.”

Armstrong at 47 looks much the same as he did at 22: like a character who’s just stepped out of a Beano strip and headed for the nearest tattoo shop. He has the air of a man who didn’t get much sleep. It emerges that he landed in Spain yesterday to discover that members of his eldest son’s band, Swimmers, were involved in a bus crash back in the US. He’s been up all night with worry. (His son, Jacob, wasn’t involved, but Swimmers’ singer was admitted to hospital.)

Father Of All… is the perfect album to kick off an already-explosive new decade. Green Day have made a deliriously terse record, infused with soul, R&B and glam rock and spasming with defiance and despair. Armstrong says he set out to make an album that sounded like “the history of rock’n’roll”, and that’s what he’s done. It arrives at a point when neither guitars nor rock’n’roll are front and centre in the cultural conversation. It’s a decision that is either insane or fearless. “Or just dumb,” says Armstrong. Either way, it’s in keeping with the spirit of the times.

Father Of All Motherfuckers may be a throwback, but it’s not redundant. Like all the top-tier Green Day albums, there’s a point to it.

“It’s a party record, but it’s also depressing,” says Armstrong, pointing to the fucked-up buffoon crawling along a dancefloor, looking for their lost phone in the marvellously titled I Was A Teenage Teenager. Nor is it a political record with a capital ‘P’ – even the title track swerves tub thumping or finger pointing. “There are political moments, but I don’t want to beat on the drum that everybody’s beating on. They’re beating it to death.”

But the best thing about the album is its brevity. It’s the perfect fit for digital-age attention spans, its 10 tracks flash by like a train. Only one, the pulsing Junkies On A High, hangs around for more than three minutes. Here and then gone. If only the man in the Oval Office would do the same.

“When we started, punk was not part of the pop culture conversation. I jumped into this style of music that I knew damn well was never going to be big. I don’t know if that was being pessimistic or if it was empowering.”

Billie Joe Armstrong

The idea of three middle-aged malcontents having anything approaching a sustainable career in 2020, let alone one as successful as Green Day’s, seems ridiculous. Almost as ridiculous as the notion of a trio of bong-huffing street rats from Northern California having anything approaching a career in the first place. Yet the evidence is on record: Dookie and American Idiot, released 10 years apart, have combined sales of 36 million.

But success shouldn’t just be measured in spreadsheets or longevity. There’s also the way a band fixes its place on the cultural landscape, their influence trickling down onto subsequent generations. And in that respect, Green Day have cleaned up.

The 1975’s Matty Healy credits them with making him want to become a musician. “I was in Green Day for five minutes,” Healy tells Q. “You know when they pull kids out of the crowd to play onstage? They did that with me in Newcastle. I played the bass. Changed my life.”

That was in 2003, when Healy was 13. It was, he says, their undiluted approach that chimed with him. “It was a realisation of that punk idea, but that was at that point filling arenas. I was, like, ‘Fuck, you can actually do this shit.’”

Matty Healy isn’t alone in holding up Green Day as an inspiration. Wolf Alice and Post Malone have both covered their songs: the former stripped bittersweet break-up ballad Good Riddance (Time Of Your Life) of its caustic edge, the latter turned 1994 single Basket Case into a stoned acoustic campfire singalong (and taught Armstrong how to play beer pong backstage at a gig). Like Healy, Lewis Capaldi and Ed Sheeran both also cite gigs by the band as formative flashpoints. Sheeran told Armstrong as much when they met. “He fan-girled out pretty good,” Armstrong recalls, laughing.

Yet none of those are as odd as the alleged fandom of reclusive director Terrence Malick, who reputedly edited his 1998 war epic The Thin Red Line with the sound turned down and a Green Day album playing in the background.

And then there’s Billie Eilish. A few weeks before we meet, Billie Joe Armstrong was interviewed alongside the 17-year-old pop wunderkind for Rolling Stone magazine. “I can’t believe I’m in the same room as the guy who was on my wallpaper,” enthused Eilish, necessitating an explanation to a confused 47-year-old punk rocker that she meant the wallpaper on her phone. “It’s so genuine what you did,” she said of Green Day’s music, which she’d come across via her older brother, Finneas.

Generation gap aside, the pair deal in the shared currency of anxiety and alienation. “When I saw her live, it was this beautiful moment where all these kids – all these young women – were singing along to these dark bedroom anthems,” says Armstrong. “It felt like kids were singing soccer anthems, but it was really dark. All that stuff is universal.”

Eilish isn’t the only contemporary artist to have caught Armstrong’s attention. He cites Kendrick Lamar as an oblique influence on Father Of All Motherfuckers in terms of “truth-telling”. But then the current wave of hip-hop and Green Day aren’t hugely removed from each other in Billie Joe Armstrong’s head.

“Post Malone, Tyla Yaweh – a lot of it is really internal and insecure with its feelings,” he says. “It’s very emo. Like, ‘Fuck, this sounds like Basket Case.’”

The reign in Spain: three’s company at Madrid’s La Riviera

A few years ago, when Billie Joe Armstrong was feeling low and adrift, he wrote a letter to himself in the voice of his father, Andy. In it, he told himself not to take life too seriously, to enjoy where he was at. “I’m proud of you,” wrote Billie Joe-as-Andy. “And I’m proud of my grandkids.”

Andy Armstrong looms large in his son’s life, even though he has been absent for most of it. Armstrong Sr, a jazz musician turned truck driver, died of cancer when Billie Joe was 10, an event poignantly memorialised in Green Day’s 2004 song, Wake Me Up When September Ends.

Losing his father was understandably tough for the young Armstrong. He found an escape in music: hard rock and ’80s metal at first, but soon tired of it and graduated to punk. “This was raw shit,” he says now. “Rock’n’roll at its most basic. It sounded real and lo-fi, not slick and processed.”

He doesn’t go so far as to say that punk saved him, but it did educate him. “That’s where I made my first friends who were anti-racist, anti-homophobic, queer kids, teenage runaways. It became a family to me. I feel like I was adopted by punk.”

The sense of community he found in punk rock, particularly at legendary Berkeley underground club 924 Gilman Street, is something he says that he still carries with him. It’s that which prompted him to travel to New Orleans to help rebuild houses in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, hammer and nails in hand. “We’re up on the roof with these volunteer kids and they’re going, ‘I didn’t expect to be here with you,’” he says.

When the 14-year-old Armstrong and Dirnt formed the earliest version of Green Day in 1986, they had no clue as to what the future would hold. They had an idea of what it wouldn’t hold, though: fame, money or any of the material trappings of success they saw on MTV.

“When we started, punk was not part of the pop culture conversation,” says Armstrong. “I jumped into this style of music that I knew damn well was never going to be big. I don’t know if that was being pessimistic or if it was empowering.”

It was Dookie that ruined his plans for obsurity. Released in February 1994, two months before Kurt Cobain’s death, its bug-eyed-Banana-Splits energy was brighter and buzzier than grunge’s shop-soiled grimness, its internal psychologies less overtly self-flagellating.

Dookie filled the hole left by Cobain with something superficially shinier – a platinum-coloured balm that propelled the three dazed musicians who made it to superstardom and turned punk from cultural curio in the US into a musical gold mine.

More than 25 years later, it stands as a touchstone for musicians who weren’t even born when it was released, from Billie Eilish to genre-mashing British maverick Rex Orange County.

“Dookie was the first record I ever bought from HMV,” says Bea Kristi, aka rising grunge-pop star Beabadoobee. Kristi, who featured in the BBC’s Sound Of 2020 longlist, is 19; she discovered Green Day via a schoolfriend when she was 14, instantly pivoting away from One Direction. “It was pop, but it was angry.”

It was the simplicity of their songs that grabbed her attention. “If a band can make great music with just power chords, you know they’re not shit.” But there was something else that provided a through-line to a record more than 25 years old.

“I thought, ‘This sounds familiar, even though it isn’t familiar. I know I never grew up in the ’90s, but it’s got this nostalgia thing. It’s super-timeless.”

If Dookie turned Green Day into a successful band, then American Idiot turned them into a vital one. The incendiary title track touched a nerve. Some loved it for its rabble-rousing spirit. Some decried it as unpatriotic. Millions bought both the single and the album it came from.

“I felt like Green Day became something important,” says Armstrong of that period. “Before, we had songs about masturbation. Now we had this song that was inspiring people. I didn’t see it as negative. I saw it as joyous.”

American Idiot also opened doors that were jammed shut before. In 2006, they collaborated with U2 on Hurricane Katrina benefit single The Saints Are Coming – a tacit Papal blessing from Bono. Weirder still, Facebook founder and Green Day fan Mark Zuckerberg asked Armstrong to play at his wedding in 2012.

“If there’s one thing I could take back…” says Armstrong now.

Facebook, he says, has shifted from social media network into propaganda machine. “Nothing against him personally, cos he seems like a nice guy. But he’s got a beast on his hands and he’s got to tame it.”

On the plus side, Zuckerberg did set up Armstrong’s first Facebook account for him. “It’s a secret one,” he says. “Nobody knows I’m on there.”

“We are ministers in the church of rock’n’roll. I believe in this shit. It’s important. A lot of popular music is not important to me. But rock’n’roll speaks to me. It’s a religion.”

Mike Dirnt

While he was writing Father Of All…, Billie Joe Armstrong came across a tweet referencing the recent spate of deaths in hip-hop: Lil Peep, Mac Miller, XXXTentacion. “This kid said, ‘Death has become the best marketing tool for the music industry.’

I was, like, ‘Wow, that’s so true.’”

The tweet inspired a line in the track Junkies On A High. In it Armstrong sings: “Rock and roll tragedy/I think the next one could be me.” He denies it’s autobiographical, but it’s hard not to draw parallels with his own life.

In September 2012, a drunk and riled-up Armstrong smashed a guitar and stormed offstage during a very public meltdown at a gig for streaming service IHeartRadio in Las Vegas. Unluckily for him, it was captured on camera. Worse, the timing was lousy – it happened days before the release of Uno!, the first in a grand trilogy of albums that were ultimately sunk by the singer’s flame-out.

In the hairshirt interviews that followed, Armstrong admitted that the incident was a product of an out-of-control addiction to alcohol and prescription drugs. He gave up booze and substances, and spent the next few years crucifying himself for it in the media. Today, he’s pivoted 180 degrees on that view.

“I thought it was more negative than it was,” he says. “Now, I think it was one of the most punk rock moments of the last 10 years. I should have taken it as that instead of a nervous breakdown. I know it gets pretty dark for other people that were involved, like my wife and my kids, but as a piece of theatre, it was pretty amazing.”

He’s sure he still would have gone through what he went through if he’d been a truck driver like his dad and not the singer in a world-famous band. “Probably not in front of so many people,” he says. “I did it on a massive scale. But judging from other family members, there were a lot of issues. Was it hardwired into me? Yeah, I think it was.”

Armstrong puts his problems with drink and drugs down to a need to deal with “anxiety issues”. Presumably those issues haven’t gone away?

“No,” he says. “I just have to deal with it. I have moments [laughing]. Middle-aged moments.”

There were other reasons for self-medicating. “There’s a lot of PTSD that’s happened in my life. Growing up in difficult circumstances, without parents around. But I’m dealing with it.”

Did the suicides of peers like Chris Cornell and Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington affect him? Was he on that same path at any point?

“No, I don’t think so. I don’t think I have those kind of dark tendencies where I would kill myself. Self-destructive, yeah, but I’m not going to take myself out.”

Is he still sober? He shrugs non-committally.

“I try to choose my moments more nowadays,” he says, which means ‘no’. “I’m not Mr Sober or anything like that, but I lay off anything that’s kind of a ‘down’ narcotic. I did have five years where it was nice just to clear my head out.”

Is he worried about slipping back into bad habits?

“I go through cycles where I’m really healthy, then I’ll get that feeling where I’m not… having enough fun. There’s a fine line between partying and celebrating and I definitely walk it sometimes. It’s something I’m always gonna end up dealing with, drugs and alcohol.”

“We’re a teenage rock’n’roll band in our mid-40s, and that feels great.”

Billie Joe Armstrong

Bowl with it: Green Day stay in their respective lanes at the Bless Hotel, Madrid, Spain, 29 October, 2019.

The drink and the drugs and the onstage tantrums plug into rock’n’roll’s great overarching mythology. And these 40-something teenagers are nothing if not in love with the myths of rock’n’roll.

Despite all their success, there’s something anachronistic about Green Day in 2020. With their talk of “honesty” and “authenticity”, they feel like a holdover from a different era. Mike Dirnt, particularly, brandishes the unswerving but currently unfashionable view that guitar music is the pinnacle of modern culture like a Bible.

“We are ministers in the church of rock’n’roll,” says the bassist. “I believe in this shit. It’s important. A lot of popular music is not important to me. But rock’n’roll speaks to me. It’s a religion.”

In fairness, music provided even more of a lifeline to Dirnt than his bandmates – he was raised in a troubled household by a heroin addict mother.

The 2000 people packed into the La Riviera club later that evening are on-board with those same sentiments. As promised, the first half of the set features Dookie top-to-tail in all its angsty, bamboozled glory. The second half is a run-through of their greatest hits, culminating with American Idiot’s twin highlights, the seething title track and the nine-minute punk rock opera Jesus Of Suburbia. The former has never sounded more on-the-nose. It turns out that Green Day wrote the ultimate takedown of Trump’s America 16 years ago.

Armstrong is still trying to work out how he’ll deal with the oncoming political trials of the next 12 months. He’s onside with Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and wants to get involved “if I can figure out how to do it the right way, without trying to shove a rock star’s opinion down people’s throats.” The answer, he thinks, is “trying to have something in common with people who feel slighted, who live in places like Kansas, not California.”

Barring a judicial miracle, he’s got time to work that one out. And if the worst does come to the worst, Green Day are going out dancing.

This article originally appeared in issue 409 of Q.

Words: Dave Everley Images: Michael Clement