Q

GOLD

Redemption Song

Before the drugs and the tabloids and the notoriety, Pete Doherty was half of a songwriting partnership in THE LIBERTINES with Carl Barât that lit up the early noughties with youthful, poetic exuberance. Quickly, though, the skies darkened and after two albums they split. In 2015 ANDREW PERRY travelled to their Thailand base for their first joint interview in over a decade and to discover how bridges were rebuilt – and where the cracks still lie.

Words by Andrew Perry

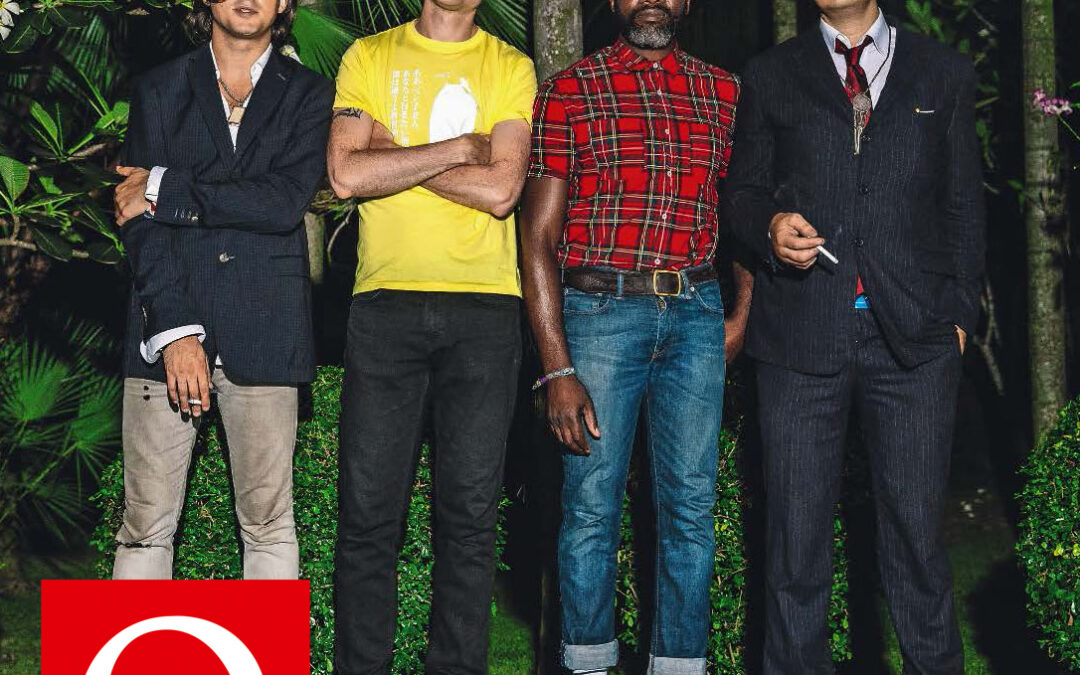

What became of the likely lads?: The Libertines (clockwise from left, Gary Powell, Carl Barât, John Hassall, Pete Doherty), Karma Sound, Bang Saray, 16 May, 2015.

You see that pack of wild dogs up ahead?” yells Pete Doherty over his shoulder, as his moped whizzes through the dusty backstreets of Bang Saray, Thailand. “When they come at us,” he advises, fag in mouth, “don’t flinch or lash out, yeah?” He gives it some throttle, and Q hangs on for dear life as Doherty accelerates through the mob of rabid mongrels. “Raaaaargh!” he hollers after we pass through unmolested. Your correspondent wimpers: “Please let me live!” The bike speeds onwards.

For the past month, Doherty has been residing at local recording studio Karma Sound, making the most eagerly anticipated British alternative rock record in years, with his reunited death-or-glory band, The Libertines. The group blew apart in 2004 amid burglary, arrests and a blizzard of hard drugs, chiefly because Doherty’s songwriting spar, co-frontman Carl Barât, wouldn’t tolerate his fledgling addiction to crack and heroin.

In the ensuing years, the two were not on speaking terms, until sporadic reunion gigs finally culminated in Doherty’s first serious effort at cleaning up last October, at the Hope Rehab Centre in the idyllic fishing village of Sriracha, an hour away from his current Thai address.

After completing the programme, he and Barât set about reigniting their creative fire out here. Reports suggested that everything was going swimmingly, but when Q arrives in Bang Saray during the fifth and final week of recording, it becomes clear that nothing is quite so cut and dried in the world of Mr Doherty.

On day one of our stay, a studio visit is cancelled due to “a tense atmosphere”. This, though, proves to be the birthing pains of a new song, and the following afternoon Doherty and Barât bugger off with a demo thereof to Bangkok, with a plan to pen the requisite lyrics on the two-hour drives there and back.

Doherty loves a bit of cat-and-mouse. On our third day, we’re to wait in a bar, while the band have lunch. Time slips by. Back at the studio, Barât holes up in his room, waiting for Doherty to surface. When the latter breezes downstairs, he goes straight to his moped. “Jump on!” he says. I, who’ve only been on two wheels twice in my life and come off both times, inexplicably comply.

“Right,” Doherty asks with a sly grin, once we’re on our way, “can you call Tony [Linkin, Libertines PR] and get Carl to meet us at the Monks In Formaldehyde?” Operating a smartphone would mean letting go. He laughs throatily.

After a journey lasting somewhere between four years and 15 minutes, Doherty pulls up at Bang Saray’s fabulously ornate Buddhist temple. He calls Barât, then marches over to an arrangement of 12 glass cabinets, set in three rows of four, each containing a robed monk statue in cross-legged meditation. Several of the cabinets are missing a pane of glass, leading Q – jet-lagged, freaked – to believe that at least some of these dudes might actually be breathing. Doherty gets up close to one, pulling funny faces.

Down some steps, he caresses a statue of Naga, the “water-snake dragon” from Buddhist scripture, who is surrounded by vengeful Furies, the infernal deities that feature in both Greek and Roman mythology. “Karma Sound used to be a snakepit,” he says, “and the locals still call it ‘the Naga place’.

“The song we’ve just written,” he adds, “is called Fury Of Chonburi – that’s this area of Thailand’s name. It’s about trying to channel that fucking darkness that we have. Amid the optimism and bonhomie and love we’ve got in the band at the moment, I dunno…” – he gazes skyward – “there’s still this fucking anguish and violence going on in us. It’s like, ‘How do we use that?’”

Those rock singers today who may plausibly claim to have hellhounds on their trail, can be counted on one finger of one hand: Peter Doherty is that man.

“Amid the optimism, bonhomie and love we’ve got in the band at the moment, there’s still anguish and violence going on.”

Pete Doherty

The Libertines have often been cited as the most important British band of their era, bridging the gap between Britpop and Arctic Monkeys. When their peculiar breed of chaos erupted at last July’s British Summer Time concert in Hyde Park, however, in front of an audience many times larger than any they’d played to during their original earlynoughties tenure, the band’s generational significance had to be reappraised.

According to Barât, the gig was “the most chilling, beautiful, assuring thing I’ve ever done. It made my whole life make sense, just for that hour – but then I got desperate for the khazi, and everybody started beating each other up and crushing each other.”

It was hardly The Libertines’ fault they had to halt the show, while desperate punters near the front were rescued from terrifying crowd surges. Still, it’s hard to shake off memories of how catastrophically they ballsed things up during their first meteoric ascent. Surely they won’t salvage defeat from the jaws of victory this time?

Some have queried the wisdom of them recording their third album so close to Bangkok, arguably the world’s heroin capital, given that Doherty has bailed on numerous rehab efforts before. Yet Karma Sound, situated five minutes up from Bang Saray’s tranquil beach, offers a zen retreat from Thailand’s stereotypical drugs/sex industry madness.

When Doherty emerged from Hope in January, he and his manager, Adrian Hunter, had no idea where to go next. Pete, clean? This was virgin territory. A return to London, or Paris, where he’d been living with his girlfriend Katia de Vidas, was not on the agenda, for obvious reasons. “After Hope came reality,” he quips.

With a view to ramping up the tentatively mooted Libertines album, Hunter Googled studios in Thailand and discovered Karma Sound. Its owner, Chris Craker, a softly-spoken ex-manager at Sony-BMG, simply told them to come straight over. Doherty and de Vidas have been there ever since.

A sleekly designed brick complex, built around a small “lengths pool” and exquisite palmed gardens, it’s got to be one of the most relaxing places on earth. As Barât observes, “You quickly realise you’re not being chased by a wasp down Holloway Road – instead, we’ve got pit vipers, scorpions, lizards…”

The Libertines have turned this idyll into a busy multi-media hub. Adjoining a naga shrine, the basement room has been filled with Libs-y clutter – a pool table, knackered guitars, four ancient typewriters, a biography of poet Arthur Rimbaud, numerous self-painted artworks (in silver pen, spraypaint, action-style splodges, but mercifully none of the syringe-applied blood of Doherty’s junkie years), and a putative set-up for their album cover, with each letter in their band name presented in unmatching frames, fringed with temple candles.

Before recording started, Barât shuttled over four times from North London, where he lives with his cellist partner, Edie Langley, and their two young children, to battery-farm new songs. Neither was certain much would come of it. Signing their first ever major deal with Virgin EMI in December, they had a safety blanket of old demoes, which never made their original two records, 2002’s raggedly furious Up The Bracket and 2004’s brink-of-collapse The Libertines. They didn’t want to fall back on those, and they haven’t had to.

“We’re extremely excited by the new stuff,” says Barât, after his moped screeches up at the temple. “It’s been great to be in the trenches again, but of course it doesn’t come without the highs and the lows, and the tos and the fros, which are part of the Libertines mantra.”

On arrival, Barât doesn’t remonstrate with Doherty for leaving without him, just denies him eye contact. Doherty cackles at him. They decide upon a beachside bar as a location for their first joint interview in 12 years.

After another hairy bike ride, the band’s favourite haunt turns out to be a colonial club-style bar run by Anglo-German expats. Shambling up across its fetishistically manicured lawn, we’re glared at by retired major types with bloodshot eyes. “You can tell there’s been a few gin and tonics,” stage-whispers Doherty.

We find a quiet table outside, and over three beers and a brandy each (Doherty’s allowed booze), this volatile double act give a guided tour of those highs and lows. They bicker constantly. Barât is surprisingly shy; Doherty’s confident but self-deprecating. Both are passionate, literate, hyper-sensitive, vulnerable, but where Barât bottles up his grievances, Doherty obsessively needles at them. The freshest was inflicted only last night, while they were both on the mic, extemporising lyrics for Fury Of Chonburi in a semi-rap style.

“We got really low down and dirty, an’ proper havin’ a pop,”Doherty reveals. “We laughed it off at the time, and it was entertaining for everybody, but actually a lot of it was really dark and hard to bear. He goes, ‘You think that it’s easy, with a friend that deceives me…’”

“Yeah, you didn’t like that one, did you?” Barât chuckles remorselessly.

A deeper division has opened up over the fittingly entitled Anthem For Doomed Youth.

“It’s a brand new belter, the song we’ve never been able to write,” says Doherty, in a pleading tone. “It was jointly written – so beautiful, the big moment on the album – and we were supposed to be singing a verse each. [Flaring up at Carl] Then you were avoiding me, and I had to learn from the engineer that you’d already done the fucking vocal take on your own. [To Q] He took advantage of me sleeping in, and he sang it so well, there’s nothing I can do.”

“I was making hay while the sun shines,” Barât shrugs.

“I just want a bit of communication,” Doherty retorts.

“You think I’m not communicative?”

“No, you need a coffee.”

There’s an intense silence, before Barât clarifies: “Pete has to choose a new bugbear for the next decade.”

Miraculously, the album is almost finished.

Boys in the band: “This is who we are. We’re proud and honoured by it.”

“Every time I went out to buy a pint of milk, I’d get asked how Pete was and when we were getting back together. I taught myself to consider it a blessing that it was part of my past.”

Carl Barât

One little riff, interpolated in the middle-eight of rousing newie Fame And Fortune, apparently dates back to 1997, when Doherty and Barât – each a university drop-out, from an itinerant upbringing – first started knocking around together.

“Carl was living in Mortlake, above a furniture shop called Planet Pine,” Doherty recalls. “He had a Kings And Queens Of The Realm tea towel on the wall, and an open fire. The first night I went over, I took my four-string guitar, and we’ve actually had that riff ever since.”

The Libertines had a messy genesis, but were signed in December 2001 by Rough Trade, as a British answer to The Strokes. As muscular New Jersey-raised drummer Gary Powell recalls, he joined barely three months earlier, while bassist John Hassall, who’d quit the band in disillusionment, was beggingly recalled once their deal was struck. Meeting those two – Powell, the eldest by eight years, a brash, garrulous character; Hassall, a teetotal, cryogenically-spoken Buddhist (even back then!) – you realise how, like countless classic groups, The Libertines were an alchemy of conflicting personalities, not just a dominant couple.

In their songs, though, Doherty and Barât often wrote about – and to – each other, mythologising themselves and their shared dreams.

“We were just children,” Barât reflects, “and in finding the world, we became tangled up in one another, and we learnt and grew together.”

“We both had this romantic vision of life,” adds Doherty, “a world we’d seen in books and films. But no matter what dream we had, or what angle we came at it from, it was always scuppered. The only place where we could succeed and triumph every time was in a song, with guitars. That was the power and the glory – the only place where we were ourselves.”

Charged by such idealism, The Libertines’ sound referenced The Smiths, skiffle and The Clash, whose musical leader, Mick Jones, recorded their two albums in breathless live takes. Their live shows were total anarchy, some among the first “guerilla gigs”, held in fans’ front rooms.

“It was just, ‘Come round and have a knees-up, tenners on the door, bring a bit of what you fancy,’” Doherty remembers, his face darkening. “At the same time, we were getting a bit of status, and we were on this conveyor belt, having to toe the line in order to reap the reward – basically, the money.

“So, it was a bit twisted, to be honest. It felt like we were betraying ourselves, and it was a dark energy that was being created – it wasn’t a celebratory thing. It was getting to the point where every gig was a riot. Everything was getting kicked over and destroyed. You couldn’t play some beautiful melodic song in the middle of the set, like Radio America – well, you could, but you’d get a fucking bottle in your face.”

“It was me making everything fast,” Barât admits, “I loved it.”

So, as documented in the second album’s Can’t Stand Me Now, the disagreements which saw Doherty sacked from the group were about more than just his narcotic preferences. In the ensuing months, Doherty pursued his other band, Babyshambles, dated Kate Moss, and, as his addiction escalated, became tabloid shock-horror material. Barât was ostensibly left to carry the can for the band’s failure.

“Every time I went out to buy a pint of milk, I’d get asked how Pete was, and when we were getting back together,” he recalls, unhappily, “but I taught myself to consider it a blessing that it was part of my past.”

Doherty, who’s been listening impassively, suddenly rises and launches over the pub table at his compadre. “Here, give me your tattoo!” he orders, putting his inner left forearm skin-to-skin with Barât’s right bicep – the spots where both have the word “libertine” inked.

“This is who we are,” he says, eyes a mixture of fire and water. “It’s so deep, so much who we are. We’re proud and honoured by it. And if it’s an off day, just fuck ’em all anyway.”

He sits down, simmering.

“The only place where we could triumph every time was in a song. That was the power and the glory – the only place where we were ourselves.”

Pete Doherty

Back at the ranch, tracks from the album, newly entitled Anthems For Doomed Youth, are aired by Jake Gosling, its producer. Eyebrows were raised when Gosling landed the job: his CV includes Ed Sheeran’s + and One Direction’s Little Things. Virgin EMI, explains Doherty, “were determined to get in somebody who’d sold records.” To their surprise, he clicked on a personal level. “The fella’s really buzzy,” Doherty enthuses.

By contrast with Mick Jones’s warts-and-all live takes, Gosling has honed Doherty and Barât’s pop smarts, allowing their every melodic hook to shine through. Doherty’s dissatisfaction with their early repertoire’s hurtling speed has clearly been addressed. Up against four upbeat tunes, a further seven are slow-building anthems, or emotionally ravaged ballads, in the vein of his pole-axingly heartfelt solo elegy for Amy Winehouse from earlier this year, Flags Of The Old Regime.

“It’s a different pace,” Doherty reasons, “but all in the same frame. Otherwise it’d be like a film noir where you had nothing but gunshots all the way through, and no beautiful dialogue.”

For his part, Barât possibly burnt off any habitual rowdiness with his recently debuted new band, The Jackals. For Doherty, it’s as if he’s emerging from 15 years of addiction and surveying the collateral damage to his dreams, feelings and friendships. One song, Dead For Love, is a sublime lament for his pal Alan Wass, who died, aged 33, during the sessions.

Doherty’s rehabilitation is an ongoing process. It would be naive to expect an addiction that’s dominated nearly half his life to be “cured” by three months in a clinic. On our final evening, indeed, his counsellor drops by. Asked about his progress, he starts to talk, then starts again:

“I was gonna say, ‘The problem is…’ – but it’s not a problem,” Doherty says. “The dilemma is: life is better without it. It’s just understanding that, and remembering that, in those moments when you feel the need. If you succumb, five seconds later you realise it’s too late, and you’re just going through the same motions.

“That’s why it is a disease. It’s an abnormality, a malfunction of the brain. It’s like skiing down the same path so many times that you’re no longer capable of going in any other direction. Financially, it’s fucking expensive, too, but in other ways that’s just as well, because it’ll cost you your health, your teeth, all your loved ones, your family, your children…”

As Nick Cave points out: drug use per se isn’t “the demons” – people use drugs to shut the demons up. Doherty has an exceptionally lively mind – he’s quite possibly the most articulate and searching interviewee in all of contemporary rock. Now 36, his second bite at the cherry with The Libertines is his big shot at redemption, at reacquiring that sense of purpose, which might adequately occupy his time, talent and intellect.

As I leave Karma Sound, Pete Doherty and his allies are laughing, goofing and looking great in a variety of suits and hats for the camera – an ever-fractious but unified gang, who now, says Gary Powell, have a mature “combat mechanism” for overcoming their differences. Here’s hoping.

This article originally appeared in issue 350 of Q.

Words: Andrew Perry Images: Rachael Wright