Mojo

FEATURE

In Xanadu

Last month, ELO’s orchestral pop maestro Jeff Lynn announced that the group’s last-ever show will take place at London’s Hyde Park next summer. In 2012, Lynn sat down with MOJO’s Keith Cameron to look back on the full unbelievable journey of Electric Light Orchestra. A journey that took him from being a Brummie lad spying on The Beatles at work in the studio to actually producing The Beatles…

Words by Keith Cameron

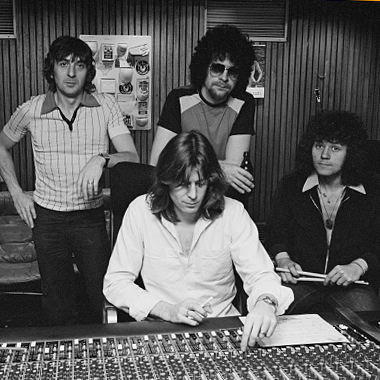

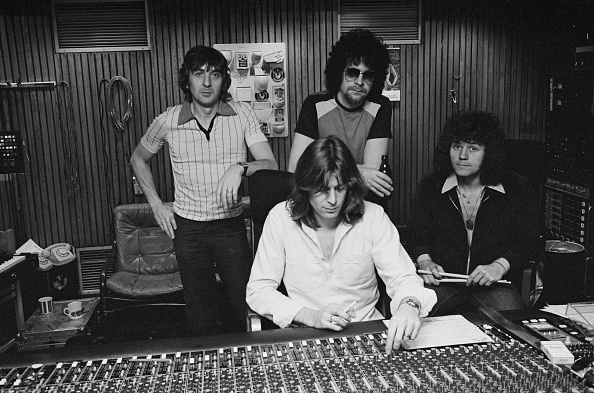

Strange Magic: ELO in a Munich recording studio (l-r) Richard Tandy, producer Reinhold Mack, Jeff Lynne and Bev Bevan, 1979

Thursday, October 10, 1968. In EMI’s Abbey Road Studio Three, Ringo Starr is at the piano, giving Paul McCartney a D note so he can start a take of Why Don’t We Do It In The Road? Through the window, transfixed, stare two 20-year-olds from Birmingham.

Jeff Lynne and Roger Spencer are the singer-guitarist and drummer respectively in The

Idle Race, a Brit-psych quartet just finishing its debut album at Advision Studios, three miles away on New Bond Street. One of the Advision engineers had casually mentioned that he knew someone at Abbey Road, if The Idle Race boys were interested in seeing what The Beatles were up to…?

It so happened that The Beatles were up to their necks in a creative frenzy as they pinged around Abbey Road hurrying to finish their contentious, confounding twin-record masterpiece, to be known as The White Album. For their part, Lynne and Spencer were a good deal more than ‘interested’. The Idle Race loved The Beatles, with songwriter Lynne particularly obsessed by the creative audacity laid bare on the Fabs’ three revolutionary records of 1967: Strawberry Fields Forever, I Am The Walrus and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. With its wonked-out vaudevillean ditties, the Idle Race’s album The Birthday Party would be emblematic of the post-Pepper landscape, while its gatefold sleeve was pure Pepper larceny, featuring a montage of famous figures superimposed on a giant banquet – The Beatles were there, along with DJ John Peel, an early Idle Race supporter. And now here’s Jeff, face-to-face with his idols.

Having relocated their lower jaws, Lynne and Spencer are ushered along to Studio Two. There they see George Martin recording the string octet’s parts for Glass Onion. Meanwhile, in the control room, there’s George Harrison and, on the day after his 28th birthday, John Lennon. “’Ello!” Lennon waves to the incredulous pair. “How you doin’?”

Even though this happened nearly 44 years ago, Jeff Lynne still goes a bit wobbly thinking about it.

“I remember Paul was playing a Fender Jazz bass, still with the price tag hanging off!” he laughs. “Then, to see George and John in the control room, looking at me! I was going, I can’t stand it… It was almost too much. I felt like a swooning school girl, ’cos I loved them so much. It was like meeting the gods.”

As good as it gets? “Aw, can’t get much better.” Jeff Lynne’s reverie suddenly halts and he raises a finger. “Unless you’re producing them!”

Face The Music: ELO do some pre-gig prep in 1976, (l-r) Mik Kaminski, Hugh McDowell, Jeff Lynne, Richard Tandy, Kelly Groucutt, Melvyn Gale & Bev Bevan

Sun is shining in the sky, there ain’t a cloud in sight… Actually, that’s not quite true. Los Angeles is hot and humid this early August morning, its regulation blue vistas seem coated with shimmering turbulence. Behind ever-present tinted sunglasses, Jeff Lynne eyes the horizon with a slight frown. As a rule, the view from the front of his Beverly Hills house offers a clear view of Catalina Island, 25 miles to the south, but today it’s barely visible as a smudge on the horizon. “Not usually like this,” says Lynne, almost apologetically. “But that’s heat-haze – not smog. It’s not yellow enough to be smog. After 17 years you become an expert on this stuff.”

Beverly Hills is a long way from Shard End, the sprawling post-war housing estate five miles east of Birmingham city centre where Jeff Lynne grew up. Yet in many aspects, most obviously his accent but also a self-effacing good-naturedness, Lynne’s roots are never far away. If this bungalow he shares with girlfriend Camelia and Lucy the dog is modest by LA rock star standards, it’s only a measure of the man. Jeff makes MOJO a cup of tea and explains that for years now he’s been meaning to build an extra storey, but it would put his studio out of action and he can’t contemplate such upheaval.

Lynne’s house literally is his studio, each room wired for sound so he can record wherever, and whenever, he feels like it. The mixing desk is next door to the lounge/kitchen/diner, where a pinboard full of photographs shows Jeff with various musical heroes and friends – two categories which, to his eternal amazement, merge into one. A framed shot of Jeff with Les Paul occupies pride of place, on top of Trevor Francis’s autobiography. In 1979, with Francis the UK’s first £1million footballer and Lynne’s Electric Light Orchestra embedded in the pop charts like a symphonic stick of candyfloss, the Birmingham blues were big news.

The only obvious sign of extravagance is the annexe, a high-ceilinged piano room with a bar, a jukebox stocked with key Lynne touchstones (Del Shannon, Roy Orbison, Everly Brothers, some obscure quartet from Liverpool), Jeff’s favourite guitar (a 1966 Fender Esquire), Fred The Robot from ELO’s 1981/82 tour and a billiard table, which MOJO wanders over to inspect, only to discover that most of its baize is covered by a massive framed presentation case, some four feet across, of every Electric Light Orchestra album, acknowledging the eye-watering collected sales of 50 million records. The wall behind the table is covered with ELO memorabilia, so it’s curious that this behemoth of baubles should remain overlooked. As will become clear, although he might wish it otherwise, ELO are far from out of Jeff Lynne’s mind.

“It can’t get better than meeting The Beatles. Unless you’re producing them.”

Amid the often ludicrous pomp of their music’s presentation, as well as some truly gruesome wardrobe mishaps, ELO were easily mocked – the gargantuan spaceship set for 1978’s Out Of The Blue tour, with malfunctioning hydraulics that left cellists trapped beneath the stage, typified the perilous nature of arena rock theatrics in the pre-digital age. But their best songs, the inimitable Livin’ Thing or Mr. Blue Sky, are timeless and ever-present and unique. That’s down to Jeff Lynne – ELO’s songwriter, producer, singer, guitarist, grafting away with a dedication that he ascribes to his father Phil.

“He was an honest, hard-working guy on the roads department of Birmingham Corporation,” says Jeff. “He could pick out tunes on the radio and play them with one finger on piano. He probably had the same musical knowledge that I did but didn’t have the opportunity I had to put it into practice.”

The influence of Phil Lynne is honoured on his son’s new album. Titled Long Wave in recognition of the music he heard as a boy on the BBC’s Light Programme (broadcast from the Droitwich transmitter in the West Midlands), it sees Lynne covering a selection of tunes from the post-war era. Thus, Bewitched, Bothered And Bewildered and If I Loved You, Broadway standards beloved of his father, get the creamy Jeff Lynne treatment. It’s a project he’s been chipping away at for the last three years.

“As a kid I used to think Rodgers & Hammerstein was a big load of posh stuff – I would

never be good enough to do that. But once you study, you realise it’s just a really clever song, brilliantly done.”

His reputation as a painstaking and efficient studio hand, as much as the adroit qualities of his own music, took Jeff Lynne beyond ELO and into orbit with his idols. After disbanding ELO in 1986, he produced George Harrison’s 1987 album, Cloud Nine, but only after cloistering himself for a year, learning about frequencies and compression ratios, the technical side of production, codifying years of practical experience into knowledge.

Cloud Nine didn’t just resuscitate George Harrison’s musical career, it changed Jeff Lynne’s life. Through his friendship with Harrison, he joined the Traveling Wilburys, where he played guitar, wrote and produced alongside Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and Roy Orbison, the singer whose voice had entranced Lynne as a boy. “I loved the Traveling Wilburys, because I didn’t have to think of everything, I didn’t have to write all the songs. We’d all be sitting round a table, strumming, and somebody would go, ‘Hey, how about this? It’s in G.’ And we’d go, ‘Oh yeah, that’s good’.” He laughs. “Of course, if Bob thinks of it, we’d go, ‘That’s great!’”

He subsequently became a go-to producer for the classic rock oligarchy – even TheBeatles, in 1994 and 1995, when he found himself helping the three surviving Fabs record Free As A Bird and Real Love from John Lennon’s demo tape DNA.

“When you’re in Birmingham and you’re playing club gigs every night, you have these dreams – and I’ve had better stuff happen than I ever dreamed of,” says Lynne. “Working with George, working with Paul, I never would have dreamed of doing that! I mean, I did dream of it, but I never thought it would ever come true. I went into making music knowing what I wanted but not knowing how to get it. Years of trial and error, and work. Work, work, work. Your voice don’t just come. Unless you’re Roy Orbison.”

At 15, listening to Only The Lonely, Jeff Lynne realised he wanted to be a producer. He heard The Big O’s unearthly croon, and marvelled. “It was a mystery to me – almost like a miracle,” he says. “How did it happen, this wonderful sound, this beautiful voice, it all sounded just perfect. Who put that together? It was the first time I thought about how a record gets made.”

In an odd premonition of his current domestic arrangements, the teenage Lynne built a primitive but functional recording studio in his parents’ living room. Perhaps because he was the youngest of four children, Phil and Nancy Lynne tolerated their son’s flights of fancy – his dad bought him his first acoustic guitar, a smart investment at £2 – though not with unreserved enthusiasm.

“My mum wasn’t a very big fan of mine. She always wanted me to pack it up and get a proper job. She used to work at ATV, in the canteen. She’d say, ‘You should see this wonderful job waiting for you.’ I was already in The Idle Race, we’d made an album by now. I said, What do you mean? I don’t want a job, I’m in a group, I’m a professional! And she said, ‘But this is a cameraman. You’d love that…’ No, I wouldn’t!”

One day Nancy Lynne opened Jeff’s bedroom drawer and found it full of money. She assumed he’d stolen it, when in fact these were his earnings from playing lead guitar with The Nightriders, the same band that Lynne used to watch at Shard End Community Centre every Saturday night. In 1963, the-then Mike Sheridan & The Nightriders were the hottest thing in Brumbeat. By day, guitarist Alan Johnson managed a branch of Burton’s tailors on Corporation Street, but by night he became ‘Big Al’, a deity in the eyes of 15-year-old Jeff Lynne, not least because at the end of gigs he would let the youngster play his Fender Stratocaster for five minutes.

“It was like having a gold-plated dream in your hand,” says Jeff. “It had a tremolo arm! It was just fantastic. He started to show me little Chuck Berry riffs. And that’s how I got into it. Big Al was a lovely chap. A great inspiration to me.”

Saturday nights at Shard End Community Centre were about dancing, though not for Jeff. He would stand on his own by the PA, staring at Big Al.

“I was all about the music. Nothing else. I mean, I used to have girlfriends, but it wasn’t serious – I wasn’t that bothered. It was just: when am I going to get that real amplifier and that real electric guitar?”

By his own estimation, Jeff Lynne’s prospects after leaving the local secondary modern weren’t the brightest. “I could go and work in any factory I wanted!” he laughs. “I started off in the top class and came second. Every year subsequently I dropped down five places. I was joint 39th in the last year. All I wanted to do was get out – get some work and get some money. Maybe buy some new strings.” In 1964, Lynne bought his first electric guitar, a Burns Sonic, on hire purchase, for £39 – “a considerable sum, especially when you’ve not got much”. After cutting his teeth with The Andicaps and The Chads, he played his first gig as a full-time professional with The Nightriders on April 4, 1966, at The Belfry. Not only was Jeff filling Big Al’s shoes, but those of Johnson’s successor, Roy Wood, an erstwhile student at Moseley College of Art who had left to form his own band, The Move.

“I met Roy at the Cedar Club in Birmingham, where all the groups used to meet up after their shows,” says Lynne. “Roy was great – we used to get on terrifically well. And we used to talk about this ELO thing, the ‘string band’. We imagined how we could do it.”

Next to The Move, thanks to presence of both Lynne and Wood in the final line-up, which duly morphed into ELO in 1972, the significance of The Idle Race in Lynne’s musical journey gets overlooked. But the band’s 1969 self-titled second album is a crucial document: it was the first record Jeff Lynne produced, and its failure to reach a wide audience hit him hard. It also reveals his compositional instincts coalescing around a wistful melancholia that clearly prefigures his greatest work with ELO. Big Chief Woolley Bosher is an austere prototype for Wild West Hero, Out Of The Blue’s widescreen heartbreaking finale, and the influence of Lynne’s Abbey Road pilgrimage is keenly felt: Girl At The Window even invokes The Beatles by name, while it isn’t hard to place Lynne’s narrative perspective vis-a-vis that song’s “lonely boy” who tempts the girl outside, “free as a bird”, and they sit together listening “to the sound of the music going round…”

As Lynne himself acknowledges, even his purportedly upbeat songs have regret – a profound sense of blue – at their core.

“I get letters saying, ‘When I’m fed up and I’ve had enough I just listen to your music and I feel great.’ That’s unbelievable, because I never felt I was doing that. Many of my songs are quite sad. Most of my favourite songs are sad songs. As for the ‘blue’, I think it’s just the other half of the whole. I think some of the blue bits are built into you and some are learned though life and wear and tear.”

Discovery: The founder members of Electric Light Orchestra (l-r) Jeff Lynne, Bev Bevan and Roy Wood in 1972

At 64, Jeff Lynne is wearing pretty well. His hair remains a Brumbrella thicket. His trousers are Sta-Prest; his Vans are slip-on. “No laces – brilliant!” he laughs. “No need to worry about your beer belly getting in the way when you bend over to tie them.” MOJO drags him over to the billiard table to inspect his ELO commemorative slab, which features the artwork from every one of the band’s original albums plus compilations. Does he have a favourite?

“Difficult to say,” he says. “I like something on all of them. And I dislike things on all of them. Probably Out Of The Blue, that was a big job, doing a double album. (Points to 1976’s A New World Record, the band’s first UK Top 10) That’s pretty good. A few good ones on there (Face The Music, 1975, first US Top 10), but the sound is a bit dull. I actually like Eldorado [1974] very much – some pretentious songs, but some really nice ones, like Can’t Get It Out Of My Head.”

Lynne looks uncomfortable confronting his past – the part of his past that defines him to the public, at least – because ELO’s ostensibly sunny legacy veils many difficult moments. The band’s early gigs were “a shambles”, and then Roy Wood left: “We weren’t getting on as well as we could have done.”

The next few years were “messy, and I don’t want to dwell on them”, as Lynne struggled to satisfactorily bed down the string element of the sound that was now his responsibility alone. By the time he’d cracked it with A New World Record, and Out Of The Blue, ELO were an unwieldy tour-weary beast. “I never liked touring,” says Lynne. “Of course, we all want to stay up all night drinking and smoking, but I always worried whether I was gonna be able to sing tomorrow. And that does not make it fun.”

He points to 1979’s hit-stuffed Discovery, ELO’s first UK Number 1 and their first without the resident string trio. “Y’know what? I’d had enough of strings by then. Making an album used to be: Oh, string day tomorrow! Fucking great! But by then it’s like: Euhhh, string day tomorrow. Do I even want strings on this?”

He admits that the albums after Discovery suffered from his resentment at being contractually obliged to make ELO records. By 1986’s Balance Of Power, following the acrimonious departure of bassist Kelly Groucutt, the group was down to a rump of Lynne, drummer Bev Bevan and keyboardist Richard Tandy. “It had run its course,” admits Lynne. “We were tired of each other.”

Yet he still can’t get those songs out of his head. Released simultaneously with Long Wave is Mr. Blue Sky: The Very Best Of Electric Light Orchestra – not another ELO compilation but some of their most famous songs completely re-recorded. Apart from a small string section and some female backing vocals, Lynne has done everything himself.

“When I used to hear those songs on the radio I’d go, Fuck, that ain’t right – I thought it was better than that! So I tried Mr Blue Sky as an experiment, to see if I could get it better. And I found that I could.”

The rest of the world might reasonably wonder how Mr Blue Sky could be improved upon. Jeff Lynne looks baffled, as if it’s the most ridiculous question ever.

“It’s a better sound,” he eventually says. “Better bass sound, better piano sound, better guitar sound, better drum sound, better harmonies sound. It’s all better. Because I know more. I know what I did in the old days and I know what I did now, so I know how much better they are. That’s what I’m saying, and I’m sticking to it!”

Given such ingrained perfectionism, it’s easy to see why he hasn’t released any bona fide new music since 2001’s Zoom (credited to ELO, it’s a solo album in all but name). Offering MOJO a warm farewell handshake, he says he’s written and recorded seven or eight new songs, and there could be an album next year. No tour, of course, but he suggests that he and Richard Tandy might get together for a one-off performance. “Me and Richard are still great pals. We just made a little film of us playing in here. It was nice not to have all the clutter and clatter going on. Nice just to hear the tune as it really is.”

He smiles, ruefully this time. “It’s difficult, but you’ve got to work. There’s no alternative to work.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 228 of MOJO

Images: Getty