Mojo

FEATURE

A Riot Of Their Own

In spring ’77, with the Sex Pistols off the road, it fell to The Clash to take punk properly UK-wide. In 2017, 40 years after, MOJO sifted the frolics, fisticuffs and fallout of the White Riot Tour to find: the real reason The Jam got fired; how much money it actually lost; and which Clash member packed his Noddy jim-jams. “It was an absolute shambles!” discovers Pat Gilbert.

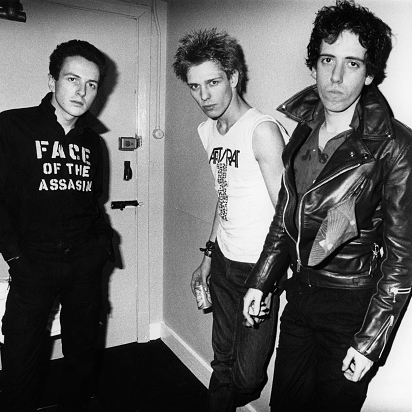

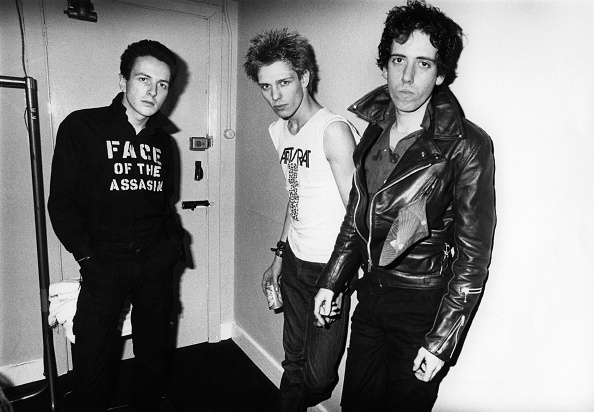

London Calling: The Clash (l-r) Joe Strummer, Paul Simonon and Mick Jones backstage at the Rainbow Theatre in 1977.

ON THE MORNING OF SUNDAY, MAY 1, 1977, AN ARTICULATED lorry pulled up in the courtyard of what is now the Stables Market in Camden Town to collect The Clash’s equipment for their first-ever national tour. The group were due to travel by coach to the opening show in Guildford later that day, and were unaware of the events unfolding in the semi-derelict, brown-brick Victorian warehouse where they rehearsed. Steve Connolly, aka Roadent, their 19-year-old confidante and roadie, had decided for added visual oomph to paint the group’s backline bright pink, but miscalculated the work involved. Consequently, the amps, speakers and flight cases were still dripping wet.

“It was an absolute shambles!” recalls their notoriously teetotal drum tech and handyman Barry ‘Baker’ Auguste, who has never before spoken publicly about his seven years working with The Clash. “We’re going out on this huge tour, and we can’t put the [protective] covers on the equipment because the paint isn’t dry. We get to the venue and the speakers are damaged and have to be repaired, all the grilles have to be screwed back on… It was complete chaos before it even started.”

And complete chaos it was. Over the next month The Clash would headline 29 dates that, for the first time, would take punk to some of the biggest rock venues in the country, at a time when the movement was as fresh as the paint on the band’s gear. The Clash’s anti-establishment rubric would express itself in exhilarating, politically charged rock’n’roll and an orgy of vandalism that would result in around £40,000’s worth of damage to hotels, vehicles and concert halls. Yet the destruction on the White Riot Tour wasn’t just collateral: the shows also marked the moment when punk itself dramatically fragmented, as the support bands – The Slits, Subway Sect, Buzzcocks and Prefects – peeled off into distinct factions, and a still-murky bust-up with The Jam caused a bitter rift with the headliners that would fester for years.

“It was called the White Riot tour,” says Topper Headon, who’d then not long joined The Clash on drums and today admits to being central to the mayhem. “But really, the Anarchy tour would have been a better name…”

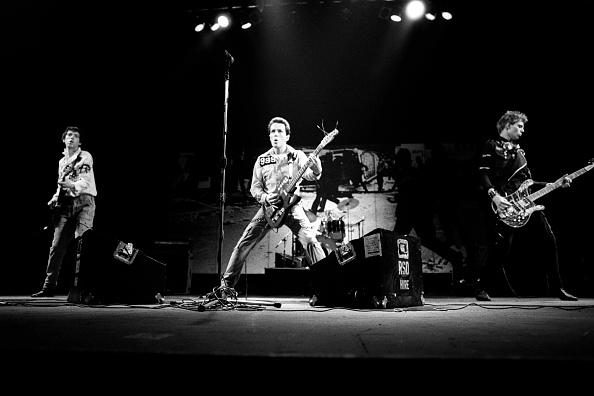

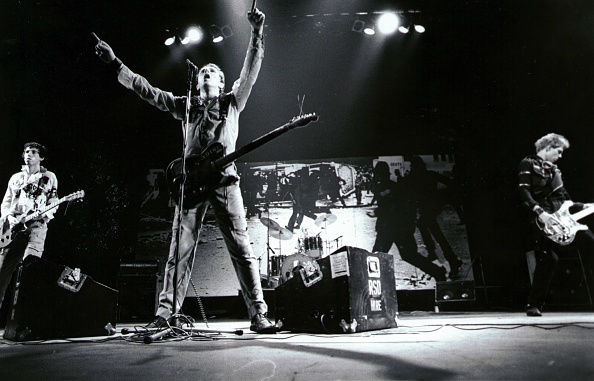

Complete Control: Jones, Strummer and Simonon live at the Rainbow Theatre in 1977.

ALMOST 40 YEARS TO THE DAY SINCE THE WHITE RIOT TOUR SET OFF from Rehearsal Rehearsals, the nickname for The Clash’s run-down Camden HQ, MOJO is sipping a coffee with Robin Banks in his Notting Hill flat. Now an urbane and actorly 63-year-old writer and film-maker, then a wayward ex-schoolfriend of Mick Jones, Banks’s outlaw activities – culminating in a prison sentence for armed robbery – were romanticised in Stay Free on The Clash’s second LP, Give ’Em Enough Rope.

Following his release, Banks had been hanging around the band since their first-album sessions at CBS studios in Whitfield Street in February 1977. Indeed, he recalls Jones excitedly spinning him an acetate of The Clash in the guitarist’s bedroom at his grandmother’s flat, on the 18th floor of Wilmcote House, a council tower block off the Harrow Road. “Mick kept asking me, repeatedly, ‘Does it sound like a real record?’” he recalls. “I don’t think any of them could believe what they’d just done.”

But a snag prevented The Clash moving forward: in March 1977 they still had no permanent drummer. Terry Chimes had given notice in November, alienated by manager Bernie Rhodes’s street-radical polemics. Having signed The Clash in January for an advance of £100,000, the CBS label expected a national tour to begin soon after the LP hit the shops on April 8. But a candidate with the correct combination of image, attitude and musical ability was proving hard to find.

“The band said they auditioned 212 drummers. I don’t know whether they did, but on the last three days the cream turned up,” remembers Baker, an 18-year-old friend of Rhodes’ other charges, Subway Sect, who’d drifted into working for The Clash the previous autumn. “I was sent to pick up Jon Moss [later of Culture Club] from this huge white mansion in Hampstead. He was good but too pretty. [Future Visage star] Rusty Egan came down. Mick quite liked him but Paul and Joe were, ‘No way!’ Then there was Mark Laff – he was a great drummer with a terrific sense of humour. He was going to get the job.”

“People looked at us as if we were Martians. The Clash in all their military-style gear, The Slits in ripped-up clothes and two Rastas.”

Robin Banks

But on Thursday, March 24, Jones, at the Finsbury Park Rainbow to see The Kinks, ran into Nicky Headon, a gifted drummer from Dover who 15 months earlier had auditioned for London SS, a pre-punk hothouse for Jones, The Damned’s Brian James and Rat Scabies, and Generation X’s Tony James. Jones invited Headon to Rehearsals the following day, but, showing signs of the wilfulness that would become a theme, the drummer “messed them about and didn’t turn up”.

With his no-show, the pressure to offer Laff the job grew, but Jones insisted they hold off another 24 hours. After an exchange of phone calls, Baker was dispatched to an address in Finsbury Park. “I knocked on the door and this little feller came dancing down the steps, going, ‘All right!’” he says. “We struck up an immediate rapport. We were both heavily into soul music and jazz. His audition was unbelievable, he was throwing in jazz things, his power was incredible.”

Headon knew what was required: in London SS, Jones had told him to “hit the drums hard”, like Jerry Nolan of the New York Dolls. Since then, Headon had been fired from both Canadian rocker Pat Travers’ band and another group, Fury, for not smacking the kit hard enough. “It’s no secret that when I joined The Clash, I thought I’d stick with them for a year to make my name and then do something more interesting musically,” he recalled. “So I thought, Whatever happens, I’m going to knock shit out of those drums. I had to re-learn my style.”

After Headon was ‘interviewed’ by Rhodes in his office upstairs, Baker was instructed to offer him the job on the way back to Finsbury Park. The next day, the drummer’s initiation into the nuanced, unsentimental world of The Clash began. First, Paul Simonon, their bassist and style overseer, dubbed him ‘Topper’, after the kids’ comic featuring the big-eared Mickey The Monkey character; then came a drastic punk makeover. “They cut my hair off and dyed it blond,” he says. “Then I was given a copy of the first album and told to learn it.”

Topper’s first task was to drum on the Capital Radio EP, recorded at CBS studios on April 3, the day after The Clash appeared on the cover of NME, Tony Parsons’ “Thinking Man’s Yobs” piece emphasising their radical politics, ‘street’ credentials and anti-racist agenda. Three weeks later, after intensive rehearsals, the band headed off to France to perform three warm-up gigs in preparation for their UK tour, booked for May. But the militant punk regimen that prevailed at their Camden HQ, and which had claimed Terry Chimes as an early victim, almost threatened to fracture the classic line-up of The Clash before it had even settled. “I remember lying on the floor of Rehearsals before we went to Paris, thinking, Shall I just get up and do a runner?” says Topper. “I didn’t know any of the people, it was totally new to me. I was scared. Thank God I didn’t run.”

Robin Banks: “It was difficult for him being the new boy. But being Topper, he very quickly developed a protective shell. He became the lunatic of the band and would take things further than anyone else.”

Baker: “Topper had to find a way to fit in. Paul was the big prankster, out for fun, looked cool. Mick was the most stand-offish but when you got to know him he was also the most caring and compassionate – he never called me ‘Baker’, which Paul came up with, always ‘Barry’. Joe was respectful, and as the oldest was looked upon as leader. Then, of course, you had to deal with Bernie – a man who thrived on chaos and creating difficult situations.”

TO ORGANISE THE WHITE RIOT TOUR, RHODES HAD employed Dave Cork and Mike Barnet of the Birmingham-based firm Endale Associates, who had promoted the Sex Pistols’ ill-starred Anarchy tour six months earlier. Like his close friend Malcolm McLaren, Rhodes had little experience of the music industry, and was spectacularly winging it. In the following weeks, he would counter complaints that the tour was a shambles with the mantra, “Listen, the whole thing was arranged from a telephone box!” Apparently, Endale’s office didn’t have a working phone.

“Nothing was laid on, hotels weren’t booked for us in advance,” explains Baker. “Dave Cork was a car-trade friend of Bernie’s [Rhodes had a side-line repairing Renault cars] and Mike Barnet was this really nerdy, librarian bloke who wore carpet slippers for the whole tour. I didn’t know what he was doing there.”

There were, however, few gripes about the music. From show one at Guildford’s Civic Hall on May 1, their bright pink amps still sticky to the touch, The Clash’s thunderous set consisted of most – if not all – of their first album, plus Capital Radio, 1977 (the B-side of the White Riot single) and a cover of Toots And The Maytals’ Pressure Drop. With Subway Sect, complete with a close-but-no-cigar Mark Laff on drums, as main support, the first few dates ran relatively smoothly. But at Swindon’s Central Hall on May 4 the first signs of disorder emerged. After the soundcheck, when the audience was piling into the venue, the fire alarm was set off and the building cleared by fire fighters and police.

Determined The Clash should never let the people down, Rhodes instructed fans to carry the equipment to the Affair nightclub opposite, where the show eventually went ahead. “We didn’t lose anything, not a single plectrum!” crows Baker. “The audience was fantastic, and at that stage a lot of them were just curious music fans, not necessarily punks. Spitting was already quite big, though.”

The following night at Liverpool Eric’s, the crew stuck black gaffa-tape over John, Paul, George and Ringo’s eyes on a Fab Four mural behind the stage. The manager threatened to cancel the show until Rhodes shouted him down. But the mayhem really began when The Slits joined the tour in Edinburgh. An all-girl band with a radically unschooled instrumental style, they were punk’s DIY manifesto incarnate, and accompanied by Roxy club DJ Don Letts acting as their manager, and Leo Williams, the club’s barman, as their roadie. “People looked at us as if we were Martians,” recalls Robin Banks. “The Clash in all their military-style gear, The Slits in ripped-up clothes and two Rastas – Don and Leo. You have to remember the context of the times. Businessmen would stare at you agape.”

That night at the Edinburgh Playhouse Theatre, The Slits’ 15-year-old singer, Ari Up, was dragged from the stage into the audience, whereupon the other Slits downed instruments and beat up her assailant. Guitarist Viv Albertine later recalled the band boarding the official White Riot coach the following morning, and immediately incurring the wrath of the fusty driver, Norman, who, alarmed at Ari’s bum-revealing dress and inability to remain seated, ordered the girls off the bus. Letts intervened and finally a compromise was reached – Ari was locked in the toilet with her ghetto blaster.

“Paul Simonon was constantly taking the piss out of The Jam. We all thought they were a mockery.”

Barry ‘Baker’ Auguste

The next night, at Manchester’s Electric Circus, Joe Strummer’s impish humour made its presence felt. “Joe said he’d found a note that had been thrown on the stage, threatening to burn down the hotel with all of us in it,” recalls Banks. “We thought nothing of it, but about 3am the fire alarm went off. The whole building was evacuated out on the street, and there was Topper wearing a pair of Noddy pyjamas (laughs). It transpired that Joe had written the note himself; the alarm was just a coincidence.”

The next morning, the bleary-eyed entourage headed south for the tour’s only London date, at the prestigious 3,000-capacity Rainbow Theatre. The Clash’s first show in the capital since their LP had hit the streets – and climbed to Number 12 in the charts – the atmosphere was electric. Throughout the afternoon, however, there were growing backstage tensions with The Jam, who’d joined the tour in Scotland. Still a suburban R&B band, who ostensibly shared little in common with The Clash’s political rabble-rousing, Subway Sect’s anti-rock stance or The Slits’ iconoclastic fem-punk, they were from the beginning a square peg. But debate still persists over why exactly they were ejected from the tour.

“The Jam left because they thought they should be headlining the show,” attests Baker. “Paul [Simonon] was constantly taking the piss out of them, we all thought they were a mockery. Weller’s dad [manager John] would come into the dressing room and start bossing everyone around. In the end, he said they wanted more money. But Joe in particular felt they weren’t right for the tour. Joe and Paul [Weller] later became good friends, but then there was a lot of animosity.”

Banks: “It was Bernie stirring it up. We liked them as individuals, especially Weller. But Bernie kept saying, ‘The Jam are going to be bigger than The Clash,’ winding everyone up. He didn’t want them on the tour and we were quite happy with it. They disappeared quietly into the night.”

Rhodes subsequently released a statement to the press, accusing The Jam of reneging on a promise to underwrite a portion of the support bands’ costs; meanwhile, the Wellers countered with a statement claiming they’d already paid Rhodes a four-figure sum – then provocatively announced they were playing several shows to celebrate the Queen’s forthcoming Silver Jubilee.

The off-stage friction fed into the Rainbow show, which ended in a mêlée as the seats were torn up and hurled onto the stage. “As soon as The Jam came on, the seats started coming up,” recalls Baker. “They were piling up at the side. Then The Clash came on and it was unbelievable – cushions, seat backs, legs, they all came flying through the air. The people at the Rainbow had never seen anything like it.”

After the exhilaration of the Rainbow riot, the tour gathered momentum and the band’s performances even greater confidence. Reckless behaviour became the norm, and shoplifting from motorway service stations almost compulsory. In Leicester, Mick Jones saluted their ever-under-siege coach driver by singing, “What a Norman!”, during the coda of Deny. One night, at a provincial hotel, Banks and Headon were unable to get into their hotel room. “The key didn’t fit in the lock,” Banks explains, “so we kicked the door off its hinges. Standing in the dark was this businessman looking rather alarmed. It turned out we had the wrong room.”

Baker: “Every single night you’d go straight into the hotel and take the fire extinguishers off the wall, because there would always be a water fight, whether it was started by Paul or Topper or the Brummie road crew. Topper would usually take the rap, even if he wasn’t there. The hotel managers loved it, they just added the damages to the bill.”

But as the tour ricocheted from Stourbridge and Plymouth to Swansea and Leeds, the mood darkened. Behind the tour’s tough, anarchic carapace, a very human scene was playing out involving Mick Jones and Viv Albertine. On-off lovers, they’d become a couple again before the tour started, but with The Slits consigned to cheap B&Bs, and the headliners busy with interviews, soundchecks and fans, they didn’t spend much time together. Mid-tour, as Albertine described in her 2015 memoir Clothes Music Boys, a romance blossomed between her and Subway Sect guitarist Rob Symmons.

When Jones, with Banks in tow, discovered the couple together in the Sect’s hotel room, a fight broke out, which left an indelible stain on inter-band relations. “The next day the tension was unbelievable,” recalls Baker. “Mick finally came out of his room and he had this huge black eye. It was one of [Mick and Viv’s] big rucks; it was never mentioned again.”

The Buzzcocks, who joined the bill at bigger venues, but travelled separately from the other groups, were also experiencing difficulties – in this case with their volatile bassist Garth Smith. They were obliged to leave the tour in its final stages, to be replaced by another teenage anti-rock act in the Slits/Subways mode, The Prefects from Birmingham. Meanwhile, The Clash’s reputation as punk’s outlaw answer to the Stones was amplified en route to St Albans, where their coach was stopped by police and the whole White Riot entourage turfed out on the roadside to be searched. “Mick gave me his dope to hide,” says Robin, “which I did, though obviously not on my own person.” The police found what they were looking for – a pillowcase and keyring taken from the Holiday Inn hotel in Newcastle; Topper and Joe were later charged with theft.

With only two nights off in a month, the tour ended on May 29 at Dunstable’s California Ballroom, where Subway Sect, Slits and The Prefects jammed a cacophonous version of Sister Ray. It was then back to London to recuperate and take stock. The Clash had performed to tens of thousands of people nationwide and established themselves as a powerful live act. But the achievement had come at a price – physical, emotional and, it transpired, financial. Strummer told the music press later that year that the White Riot tour lost the group £18,000; Baker contends that the figure was closer to £80,000 – £40,000 to underwrite travel, hotels, insurance, equipment hire, sound and lighting crews, plus a similar sum for bar bills, food, phone calls and damage to property.

Just four months after banking the £100,000 advance from CBS that had so rattled punk’s purists, the band were already skint again. Rhodes thus resolved not to pay The Clash and Subway Sect’s wages for the rest of the summer.

White Riot: Stummer in full frontman mode, 1977.

DURING THE CLASH’S ABSENCE ON TOUR, CBS followed-up the group’s debut single White Riot in a fashion that made a mockery of the group’s much-publicised contractual right to “artistic control”. Not only was Remote Control the ‘softest’ song on The Clash, but it was backed by a dodgy “live” version of London’s Burning – actually a sound studio recording for a promo film they’d shot. The group were incensed at the label’s old-school skulduggery, but there was a silver lining – it inspired what many fans still regard as their greatest-ever single. The White Riot tour, and the Remote Control debacle, exposed the fact that, apart from Capital Radio, Strummer and Jones had written no new original material since February, when Cheat was quickly knocked up for inclusion on The Clash. So it was that, in June ’77, the songwriters knuckled down to a series of intense writing sessions in Jones’s bedroom. Robin Banks was one of the first to hear the results.

“I was with a girl one night and these yobs came out of the Lyceum and attacked me, five or six of them,” he recalls. “The police arrived, let them go and nicked me! That was the danger of being a punk. I spent the night in a cell, then went straight up to Wilmcote House. Mick said, ‘What’s happened to you?’ I had blood all over the blue Lewis leather jacket he’d given me as a present. We went inside and he said, ‘Listen, we’ve just written a new song…’ It was Complete Control.”

Complete Control was one of Strummer’s first lyrics about life in The Clash – later to be a recurring theme – referencing CBS’s dealings with Remote Control, the band’s mid-White Riot tour one-night-stand in Amsterdam (on May 14), hassles from police, and smuggling fans into provincial concert halls. It was followed that month by (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais, Strummer penning the words after attending an edgy Jamaican all-nighter with Roadent on June 4/5, and for which Jones crafted a backing track that hybridised punk rock and reggae into an exhilarating new form.

The two tracks, together with The Prisoner and Pressure Drop, were recorded at Sarm West studios in Whitechapel in the last week of July, with Jamaican dub general Lee Perry – hanging out in London with an exiled, post-shooting Bob Marley – producing. Perry’s version of Complete Control was later remixed, as his dubby treatment sadly didn’t suit the song; even more frustratingly for posterity, his work on White Man was never completed due to The Clash’s impending engagement at the Mont De Marsan Festival in south-west France on August 5.

The show, in a bullring with The Damned also on the bill, proved to be an appropriately anarchic and unusual setting to debut White Man and its future B-side The Prisoner. “Before the show, Bernie told me to climb up a ladder with some spray paint and write, ‘This is Joe Public speaking!’ behind the stage,” recalls Baker. “All the Frenchies were trying to get me off the ladder, it was insane. Then halfway through The Clash’s set Captain Sensible casually walked on the stage and let off two stink bombs. So amid all the political ferocity there was this most juvenile of schoolboy pranks. Joe couldn’t even sing the words. I was livid! I caught up with Sensible under the stage and I threw him against the wall.”

The White Riot tour may have been over, but, for The Clash, newly armed with several of their greatest-ever songs, another eight years of pandemonium had only just begun.

This article originally appeared in Issue 285 of MOJO

Images: Getty