Mojo

FEATURE

Every Loser Wins

No rock’n’roll band failed quite like The Replacements: proudly, spectacularly, hilariously, famously. Their poignant punk made tough guys melt, but behind the scrappy heroics were people drawn by tragedy to self-destruction. “It was a sure bet that they were going to do something ridiculous or outrageous or insulting,” discovers Bob Mehr.

Pleased To Meet Me: The Replacements in 1989 (l-r) Slim Dunlap, Tommy Stinson, Paul Westerberg and Chris Mars.

DECEMBER, 1984: NEW YORK CITY PUNK MECCA CBGB’S IS hosting a Sunday night concert by a band calling itself “Gary & The Boners”. This puerile bit of billing is a deception, however. The group headlining this secret show is actually one of the hottest properties in underground rock: The Replacements.

During indie rock’s annus mirabilis of 1984 – which saw era-defining releases from R.E.M., Hüsker Dü and the Minutemen – The Replacements have joyously and irreverently captured the Zeitgeist. Comprising singer-songwriter Paul Westerberg, guitarist Bob Stinson, his younger brother bassist Tommy Stinson and drummer Chris Mars, the Minneapolis combo has developed a reputation for unpredictable shows and perverse career moves. Constantly courting flame-out, the band – nicknamed The Placemats, or ’Mats by adherents – is known for trusting its heart before its head.

Yet their fourth album for hometown label Twin/Tone, with its Beatles-mocking title Let It Be, has been dubbed an instant classic, and a couple of weeks before Christmas The Replacements arrive in NYC on a wave of critical momentum, hard on the heels of a cover story in the Village Voice. The buzz on the band has reached New York’s major label A&R community, whose members are eagerly jockeying for the chance to sign them.

Ahead of a bigger concert at Irving Plaza, the pseudonymous CBGB’s gig has become an unofficial label showcase. It should be the band’s crowning moment, but those who know The Replacements know better. “If they were aware that important people were in the audience, it was a sure bet that they were going to do something ridiculous or outrageous or insulting,” says the group’s long-suffering manager Peter Jesperson.

Sure enough, at CBGB’s the band spend two hours blowing raspberries at the assembled A&R men, their set becoming a drunken lollapalooza of mangled cover songs and comedy routines. They begin with You’re A Mean One, Mr Grinch, move to their own anthem of disaffection Color Me Impressed, then zigzag randomly from Dolly Parton’s Jolene to Led Zeppelin’s Misty Mountain Hop, before getting their roadie up to sing Elvis Presley’s Do The Clam.

Late in the set, Kiss bassist Gene Simmons saunters into the club to check out the scene. Alerted to the God Of Thunder’s presence, the band immediately slams into its cover of Kiss’s Black Diamond – one of the unexpected highlights of Let It Be – though their version is so sour it literally chases Simmons from the venue. They follow up with an X-rated version of The Ballad Of Jed Clampett, then whistle their way through the Theme From The Andy Griffith Show, before finally leaving the stage. “This is our last, last fucking performance ever,” croaks Westerberg amid the chaos.

The band’s minders are crestfallen, having watched all the potential label suitors flee the club, shaking their heads in disbelief at such flagrant self-sabotage.

The upshot would come just a few nights later at Irving Plaza. With the pressure off, and not a record exec in sight, The Replacements are focused and ferocious, playing what almost everyone judges to be the best show of their career. Fortunately, one music business rebel happens to be there. Sire co-founder Seymour Stein – no stranger to difficult groups, having worked with the Ramones and Dead Boys, among others – instantly falls in love and promptly signs The Replacements.

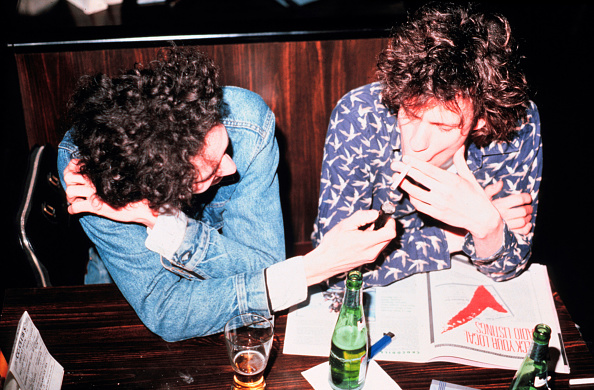

Can’t Hardly Wait: The Replacements’ lead guitarist Slim Dunlap and lead singer/guitarist Paul Westerberg in 1987.

THE GROUP HAD COME together five years earlier, in December 1979, a basement outfit from the wintry Land Of 10,000 Lakes. They were children of war veterans and alcoholics, from families steeped in mental illness and abuse, products of Midwestern recalcitrance and repression. “That held the bond in a peculiar way,” said front man Paul Westerberg. “We hit it off in ways that normal guys don’t. We understood each other.”

The most troubled member of the band, Bob Stinson had spent his teen years in juvenile jails and group homes, dealing with the aftermath of physical and mental abuse he’d suffered as a child.

He returned to his family determined to start a rock band, only to find his little brother Tommy heading down the same dead-end path. Instead he put a bass in his hands, and added Chris Mars – a shy artsy neighbour – on drums and launched a backyard party band called Dogbreath. The son of a Cadillac salesman, Paul Westerberg was a janitor and aspiring songwriter who’d kicked around playing lead guitar in suburban bands for half a decade. Passing the Stinson house on his way back from work, he heard Dogbreath jamming and saw an opportunity to harness their “delinquent energy”.

Joining forces, they would mix the music they’d absorbed throughout the ’70s – bubblegum pop, classic rock, and punk – and turn their limitations, both musical and personal, into strengths. As Westerberg would note, there wasn’t a high school diploma or a driver’s licence among the four of them. “On our own we were helpless losers,” he would say. “Together we were a band… of helpless losers.”

Their first gig came – ironically enough, given their future reputation – at a sober dance. At the time, they were billing themselves as the Impediments, a moniker they chucked after they were kicked out of the venue for drinking and threatened with a local blackball. From then on they were The Replacements – a nod to the fact that they were replacing themselves.

“We liked the funky quirks of the classic rock bands – the Who, the Stones, the Ramones.”

Paul Westerberg

Their career might’ve faded after a few months but for Peter Jesperson. A Minneapolis record store manager, nightclub DJ and co-founder of the city’s hip new wave label, Twin/Tone, he signed them after listening to a demo Westerberg had brought by the shop. “You mean you think this shit is worth recording?” replied a shocked Westerberg when Jesperson offered a deal.

The group’s debut, 1981’s Sorry Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash was a insolent blast of American punk rock, wrapped in Westerberg’s subtly sophisticated lyricism and sly rock mythmaking. Recorded in a single day, the mini-LP Stink would follow in early 1982 – a record that at once embraced the hardcore sound while effectively sending up the genre. By 1983 The Replacements were chafing at the shackles of punk/hardcore orthodoxy entirely. That philosophy would lead to the stylistic free-for-all of Hootenanny, and eventually find its apotheosis a year later with the more refined vision of Let It Be.

Tommy Stinson – who’d joined the band aged 12, quit school to hit the road at 15, and began drinking soon after – saw The Replacements’ ballooning mid-’80s mythos as “drunken, loveable losers” as both a calling card and a curse. “That self-sabotage, we got onto it early and stuck with it way too long,” he said. “People still come up to me and say, ‘I saw you play and you were so fucking trashed, it was the best show of my life.’ I’m thinking, What could’ve been so great about that?”

BY EARLY 1985, THANKS TO Seymour Stein’s patronage, the band was officially part of the presitigous Warner Bros family, which owned Sire. Though they’d cut demos with Box Tops/Big Star singer Alex Chilton – who’d opened the ill-fated CBGB’s show and lapped up the band’s nose-thumbing act – it was Ramones architect Tommy ‘Ramone’ Erdelyi who was tapped to make their major label debut, Tim.

While there would be complaints about the sound – Erdelyi’s production was derided as thin – the album would become a classic owing to a batch of Westerberg’s best songs: the generational howl of Bastards Of Young, the romantic ode to college radio Left Of The Dial, and stark drunkard’s lament Here Comes A Regular.

But the album felt less like a beginning than an end. Guitarist Bob Stinson had been absent for most of the sessions. Feeling estranged from the group creatively, and getting deeper into substance abuse, he began a protracted divorce from the band. Bob had provided emotional spark and on-stage daring – playing madcap guitar in dresses, diapers or totally nude – but had slowly been marginalised by Westerberg and his songs, particularly the ballads. “Save that for your solo album, Paul,” Stinson would tell him dismissively. But signing to Warner Bros fully tipped the balance of power. “I don’t know if there was a moment where he thought, ‘This is no longer my band,’” said Westerberg. “Because when we played the loud, fast shit, it was his band. But I felt like I can only do so much of that.”

The Tim tour further highlighted the professional pitfalls of The Replacements’ inability to play it straight. Following a troublesome appearance on NBC’s Saturday Night Live – in which Westerberg cursed, Bob Stinson flashed his bare ass, and the band destroyed a dressing room – they were banned by the network, and wouldn’t appear on US television for another three years.

The end of the album cycle brought a housecleaning meant to steady their career. After six years as their manager, label benefactor, and babysitter, Peter Jesperson parted ways with the band, replaced by the duo of Russ Rieger and Gary Hobbib. “I felt,” recalled Jesperson, “like I’d been kicked out of a club I’d help start.”

A few months later, things with Bob Stinson finally came to a head. “We were doing demos, recording… and he didn’t show up and that was the last straw,” recalled Westerberg. The reality of being in a band with Bob was no longer tenable. Something needed to be done. So during a barroom band meeting, Westerberg told Mars and Tommy Stinson he would quit the group. “I was ready to go solo. And [Chris and Tommy] said, very sweetly, ‘Well, like, who’s going to play bass with you? Who’s going to play drums? I thought, Well, do you guys wanna? Tommy and Chris wanted to stick with it. So then it became, ‘What are we going to do about Bob?’”

In the end, the decision – the very fate of The Replacements – came down to Tommy Stinson. Westerberg and Mars eyed the bassist intently, awaiting a verdict. After a long silence, he spoke up: “Well,” he sighed, “I guess we gotta fire my brother.” “In essence,” observed Westerberg later, “Tommy stepped up to save The Replacements.” However, the relationship between the two Stinsons would never fully recover (and after a decade kicking around various local bands, Bob would die tragically in 1995, felled by premature organ failure at the age of 35).

With Bob gone, and the group freed to explore new sonic territory, they headed south to Memphis to record with producer Jim Dickinson, an outsized character and recording studio raconteur whose CV included sessions with The Rolling Stones and Big Star. Cut as a trio with Westerberg handling lead guitar duties, Pleased To Meet Me was a noisy, crackling slab of high/low production values that saw Dickinson shepherd the band’s further evolution with the genteel folk of Skyway, the cocktail jazz of Nightclub Jitters, and the soul-pop of Can’t Hardly Wait (replete with brass from the Memphis Horns and Box Tops-like strings).

In early 1987, with new guitarist Bob ‘Slim’ Dunlap on board, Seymour Stein threw a playback party in Memphis, hoping to rally Warners’ promo staff to the cause, with a gold record the goal. Fatefully, the label chose The Ledge – a minor key rocker about suicide – as the lead single. Released just as a series of teen suicide pacts began dominating the headlines, MTV rejected the video and wary radio programmers stopped playing the song soon after. Pleased To Meet Me would stall at 175,000 copies.

Merry Go round: (clockwise from bottom left) Westerberg, Foley, Dunlap and Stinson in San Francisco, 1991

EVEN SO, HOPES FOR THE REPLACEMENTS’ NEXT album were high among their champions at Warner Bros. The label searched for a producer capable of midwifing their breakthrough: big names, from Stones veteran Jimmy Miller to Bon Jovi hitmaster Bob Rock, were considered. Ultimately, the band would decamp to Bearsville studios in upstate New York with Tony Berg, who’d served as Bette Midler’s musical director and Jack Nitzsche’s right-hand man, but sessions quickly degenerated into a buccaneering romp of drink, drugs and studio destruction. “It was like producing pirates,” says Berg. “They had everything but the Jolly Roger waving.”

Picking up the pieces was up-and-coming Matt Wallace, who would go on to helm hits for Faith No More and, later, Maroon 5. Though he also faced the band’s wrath – besides having to fight them from drunkenly erasing the master tapes – Wallace managed to make the expansive, dark-pop record Westerberg had been envisioning, although some of those qualities were diminished by a slick Chris Lord-Alge mix commissioned by management, without the hitmaking upside. “I wonder why a million people like R.E.M., for instance, and only 200,000 like us,” mused Westerberg in its wake. “Are they better than us, or have the other 800,000 not had the chance to hear us? If this record doesn’t sell I wanna know people heard it and decided, ‘Piece of shit, I don’t like it.’ Then we can get back to the basement, where we belong.”

Don’t Tell A Soul’s first single – the snappy call-and-response number I’ll Be You – showed signs of being a hit, heading towards the Top 40 before sputtering. To restore momentum The Replacements undertook a summer tour opening for Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers, but even at their most antagonising the group drew a lukewarm reception. “It was like playing a tiny club where no one cared – except there was 20,000 of them every night,” said Westerberg. “I mean, the rejection of a small club is one thing. But the rejection of a small city was tough.”

“That self-sabotage, we got onto it early and stuck with it way too long.”

Tommy Stinson

The failure of Don’t Tell A Soul convinced Westerberg his career prospects were better going solo, although not before a final Replacements album (in name only – All Shook Down was a downbeat singer-songwriter collection with a star-studded crew of session players, including John Cale, Los Lobos’s Steve Berlin, and the Heartbreakers’ Benmont Tench, produced by R.E.M. consigliere Scott Litt).

The album was released as Westerberg – who’d reached a “near-death” state of alcoholic toxicity – decided to give up the bottle. Sobriety shone a light on the band’s failing relationships, and a bitter bust-up with Chris Mars – whose input and role in the band had been steadily reduced – followed after comments Westerberg made in the press about his playing. (Mars would record a pair of solo albums for Island imprint Smash before finding a successful second career as a visual artist). Minneapolis trapsman Steve Foley would take over the drum stool for The Replacements’ final tour in 1991, a funereal affair that Westerberg referred to as a “travelling wake.”

Their farewell came in front of a huge festival crowd in Chicago on Independence Day 1991. At set’s end they ceremonially handed off their instruments to their roadies to play. Tommy Stinson was last on stage, riffing over a blues vamp, offering shades of Johnny Rotten’s Sex Pistols adieu.

“Yeah, you were robbed,” Stinson bellowed at the audience. “And I was robbed at birth. And I’m still being robbed!”

The symbolic hand-off had been a fitting final gesture. The Replacements had been replaced.

WITHIN A FEW MONTHS OF THE GROUP’S apparent demise, a funny thing happened: Nirvana exploded. By early 1992, the Seattle trio’s Geffen debut Nevermind was shifting 300,000 copies a week, roughly what the best-selling Replacements albums had sold in total.

Pundits would suggest Nirvana had picked up the proverbial torch that The Replacements had fumbled, but Westerberg thought they had little in common: “I guess I wore a plaid shirt and yes, I played real loud but… Nirvana sounds to me like Boston with a hair up its ass.”

It was the start of a reputational upswing for The Replacements, but it seemed too little, too late for its prime movers.

Westerberg’s own major label career expired as the ’90s ended, after a couple of disappointing solo records for Warner Bros and a piano-album departure for Capitol that the label orphaned on its release.

Tommy Stinson would struggle with a pair of post-Replacements bands, before having to get a job as a telemarketer. Though he’d sworn himself to rock’n’roll as a kid, Stinson experienced an epiphany of another kind while making cold calls selling office supplies. “In the process, I learned how to sell myself,” he said. “And I got out of the Replacements mindset – that self-sabotage, self-defeating shit.”

The ’00s were better. Westerberg returned to the indie ranks, releasing a series of reinvigorated records for the Vagrant and Fat Possum labels. Stinson, somewhat improbably, joined Guns N’Roses, and became Axl Rose’s musical lieutenant for the better part of 15 years.

Offers to reform The Replacements came up annually, becoming more lucrative with each passing year, but Westerberg resisted. “When I listen to those first few Replacements records,” he said in 2008, “I think, Could I go out and do that again?”

The catalyst finally came in 2012 after Slim Dunlap suffered a debilitating stroke. As part of an effort to defray his medical costs, Westerberg and Stinson regrouped and recorded an EP of Dunlap’s songs and covers. This would lead to series of rapturously received Replacements reunion shows (with drummer Josh Freese and guitarist Dave Minehan filling out the live line-up) in the fall of 2013. They played on and off until summer 2015, when Westerberg announced that a festival appearance in Portugal would be their last ever performance (naturally, that remains to be seen).

In the midst of their return, The Replacements were named among the finalists for induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. They lost out, of course, but Westerberg was encouraged to think that the band had earned their nomination.

“We liked all of the funky quirks of the classic rock bands – The Who, The Rolling Stones, the Ramones,” mused Westerberg. “We didn’t have the things that made those bands huge; we had the thing that made them infamous and decadent and, perhaps, great.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 274 of MOJO

Images: Getty