Mojo

FEATURE

The Greatest Show On Earth!

In the autumn of 1975 Bob Dylan took a ragtag gypsy circus on the road. The aim: to rekindle his lifelong love of performance. There would be clowns in whiteface, musos flying by the seat of their pants, laughter and tears and an incomprehensible four-hour movie. In 2019 Michael Simmons tracked down its survivors and felt its reverberations: “It was an amazing cultural event that we’ll never see again.”

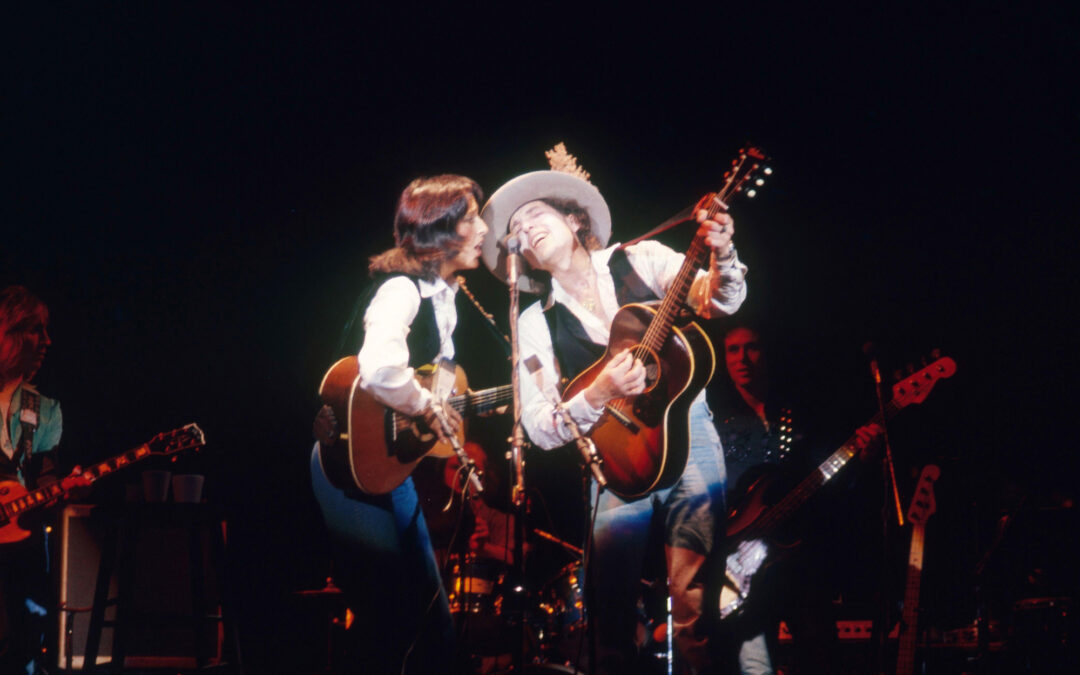

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan in concert during the Rolling Thunder Revue, at the Civic Center, Springfield, MA, 1975.

DID YOU HEAR ABOUT THAT BOB DYLAN CONCERT?” 19-year-old Dylan devotee Jeff Friedman had to check he’d heard his friend Bruce straight. What Bob Dylan concert? Friedman had heard nothing in the press or on the rock grapevine, but Bruce booked concerts at Brooklyn College, New York, and had a friend at Southeastern Massachusetts University in North Dartmouth who’d been offered a Bob Dylan/Roger McGuinn show. It was an unheard-of combo of world-shaking rock artists and backwater New England venue.

Friedman, hyperventilating, grabbed a pile of coins and called SMU. “Finally I get the right guy and I say, Are you having a Bob Dylan/Roger McGuinn concert? And he says, ‘No we’re not.’ My heart sinks.”

But the guy hadn’t finished his sentence. “‘…we’re having a Bob Dylan /Joan Baez concert.’”

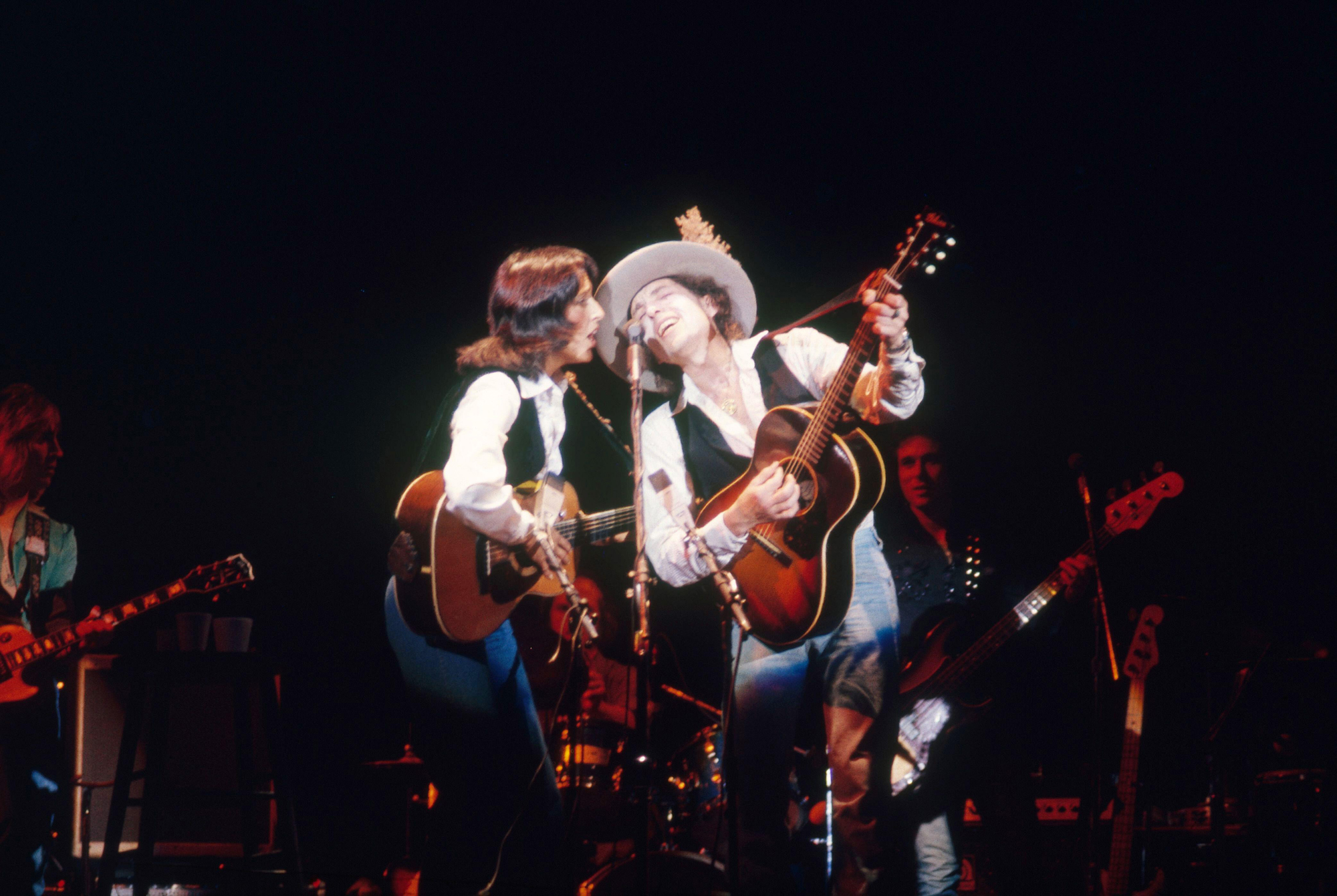

Friedman went from nerve-wracked to crushed to astonished in a matter of seconds. That Saturday, November 1, 1975, he borrowed his mother’s car and drove with his friend Ruth to SMU. Queuing outside the college’s gymnasium for four hours, he scored two tickets for $7.50 each: “I’m like, Is this really happening?”

They entered the gymnasium and grabbed two folding chairs in the sixth row. The show – the tour’s third – began with a sprawling band on-stage, none of whom Friedman recognised. “I was like, Is he gonna be here? Is he really gonna come out? And then that’s it, he’s fuckin’ there!”

Dylan led with When I Paint My Masterpiece, a duet with Bobby Neuwirth; it would remain the opener for the entire 1975 leg of what was destined to become one of the most storied of rock tours. Dylan’s performance was focused, dynamic. “And this was intimate,” says Friedman. “There was no distance between him and the audience. He was a different musician. Totally loose, not uptight at all.”

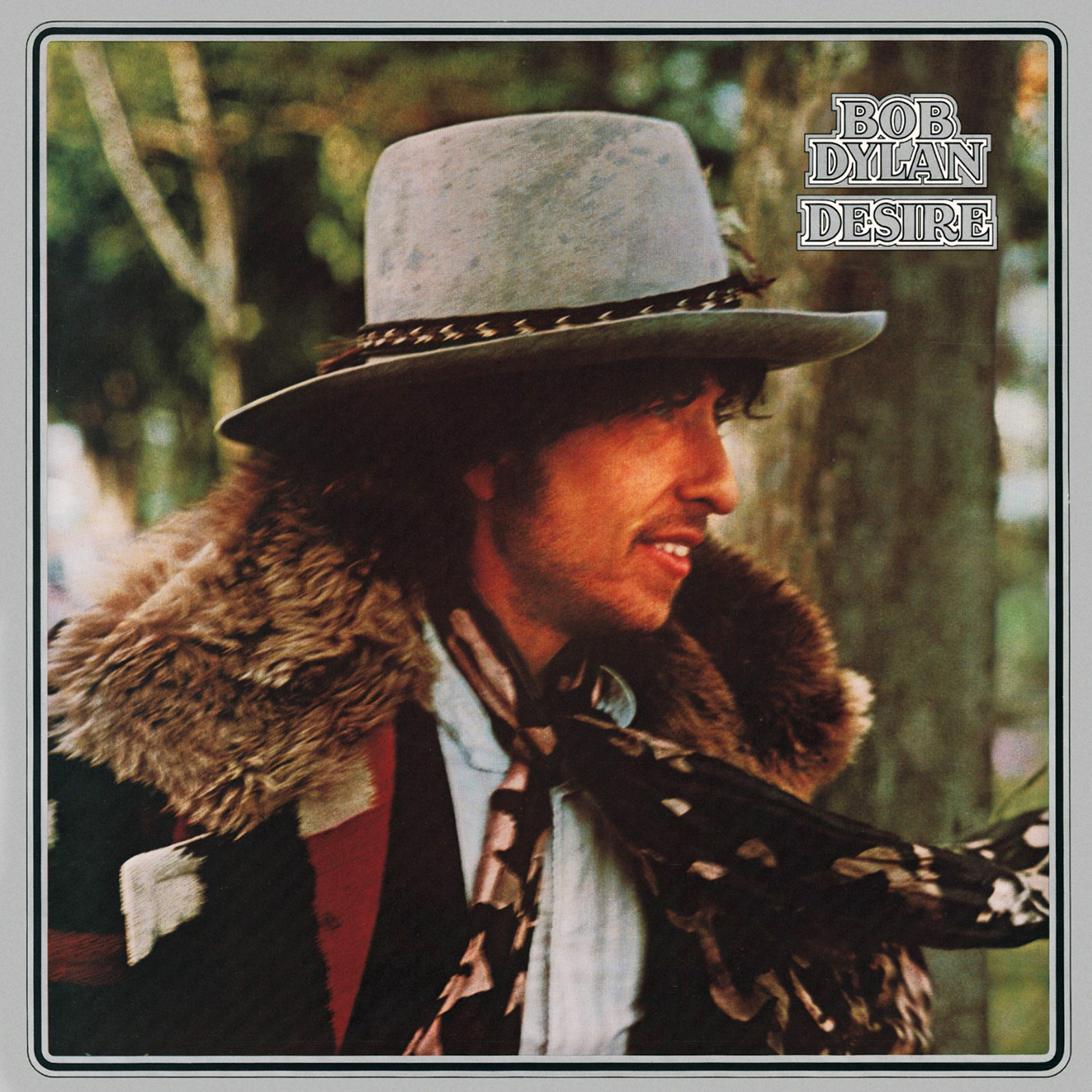

A half-dozen songs from Dylan’s set would be on his forthcoming LP, Desire. The rest were classics including It Ain’t Me, Babe; A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall; Just Like A Woman. Behind the singer, the ragtag band, including a mysterious woman playing gypsy-like violin, built a wall of sound. “Old songs that had been acoustic were now electric,” Friedman recalls. “He turned them inside out and they fit the band perfectly.”

There were four duets with Baez – the first time in a decade The King and Queen Of Folk had sung together. And the show wrapped with the entire cast singing Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land. It was as if a fresh autumn breeze had blown Dylan’s problematic early 1970s away. “He wasn’t just going through the motions,” says Friedman. “He was taking his time with the material and going deep. And they were all clearly having fun.”

“Bob said, ‘I don’t care if we make a profit as long as we break even… I wanna shoot a movie too.’”

Louie Kemp

THE STUFF OFF THE MAIN ROAD WAS WHERE the force of reality was,” Bob Dylan told interviewer Bill Flanagan in 2009. He recounted memories of carnival acts he was drawn to in mid-century Minnesota: “The side show performers – bluegrass singers, the black cowboy with chaps and a lariat doing rope tricks. Miss Europe, Quasimodo, the Bearded Lady, the half-man half-woman… I remember it like it was yesterday.”

In 1975, the appeal of the “main road” to Bob Dylan was limited. After virtually retiring from performance in 1966 at the height of his first wave of success and becoming “the Howard Hughes of rock” for eight years, he returned to live concerts in 1974 with a tour of stadiums with The Band. Yet he didn’t enjoy rock star touring, deriding it as “jets and limos”.

“Performing has always been his passion,” says his friend, the writer Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman. “But getting back on the road with The Band wasn’t satisfying. It was an alienating experience, going from stadium to stadium, not knowing what city they were in. He’d always been connected to the street – there’s a part of him that’s a street guy.”

Dylan and first aide Bobby Neuwirth had years before discussed a no-pressure musical jaunt in a station wagon. “The idea for the Rolling Thunder Revue was hatched by the two Bobs,” singer-songwriter Steven Soles told MOJO in 2012: “This was spoken very clearly by Neuwirth to me.” But a good idea has many fathers. Dylan songwriting collaborator Jacques Levy said he’d also suggested “a tour like lowest-of-the-low theatre tours. Just call it Bus & Truck. We’ll hire a couple of trucks and equipment and just go on the road.”

With his marriage to Sara Dylan increasingly rocky, the 34-year-old Dylan was in the south of France in May ’75 with painter pal David Oppenheim. Ratso Sloman remembers Bob’s account of “sitting on the back of a cart in Corsica, and he realised his destiny was to be performing in front of people.” He was soon headed back to America.

“There were entirely too many guitar players, man. You had ten guys playin’ a fuckin’ G chord! But it looked good.”

Rob Stoner

ONE HALLMARK OF GENIUS IS THE ABILITY TO realise one’s wildest dreams. Throughout Dylan’s career, he’s moved backwards in order to move forward, as if time is fluid. By June ’75, he was hanging out in Greenwich Village in New York, the scene of his early ascendance, seeing old friends and making new ones.

Theatrical director Jacques Levy had already co-written songs with Roger McGuinn, notably The Byrds’ Chestnut Mare. He lived on LaGuardia Place, around the corner from The Other End, a hub for singer-songwriters on Bleecker Street. Dylan and Levy ran into each other on the street and Bob suggested they collaborate. Levy unleashed Dylan’s theatrical inclination and worked with him to create songs that worked visually. Meanwhile, he met an artist friend of Dylan’s named Claudia Carr, and they soon fell in love. When Bob and Jacques’ work was done, they’d head over to The Other End to drink and hang out.

“I bumped into Bobby Neuwirth,” recalled Steven Soles. “He said, ‘I’m playing The Other End next week,’ and he asked me if I’d play with him.” An article in the July 22, 1975 edition of The New York Times, headlined “Dylan Makes Other End Scene”, describes Neuwirth’s residency and mentions folk vet Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Bowie guitarist Mick Ronson as two guests. An unnamed friend was quoted as saying that Dylan “was elated to find that he could once again walk into a club and play music without being mobbed or distracted.”

Neuwirth also enlisted bassist/singer Rob Stoner, drummer/pianist Howie Wyeth and eclectic multi-instrumentalist David Mansfield. Then there were a string of guests who’d show up and play. “That was Neuwirth’s idea,” says Soles. “He’d have a band of people who could sing their own songs and people could come sit in.” One night, singer/songwriter/actress Ronee Blakley – widely acclaimed for her role as a depressed country singer in Robert Altman’s Nashville – played four-handed piano with Dylan. After another show, Soles, Neuwirth, Stoner, Levy and Dylan went over to painter Larry Poons’ crib, joined by poet/rocker Patti Smith and Texas musician T Bone Burnett. “We all played songs,” says Soles. “Dylan played a number of songs that would appear on Desire.”

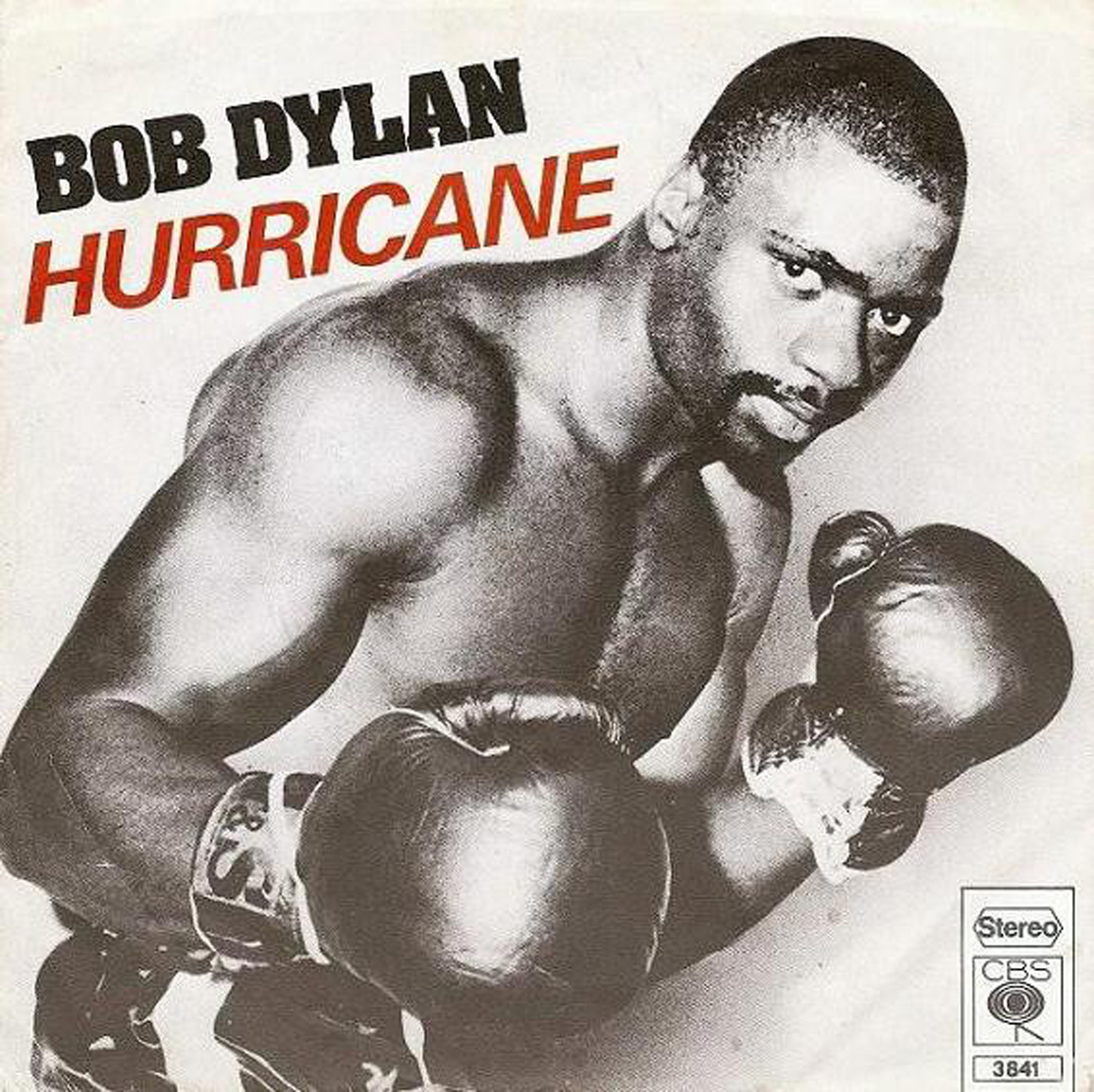

According to Soles, Dylan stayed up all night and the next morning visited boxer Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter in prison. Carter and another man named John Artis had been convicted of the 1966 murder of three patrons in a bar in Paterson, New Jersey. Carter wrote a memoir called The Sixteenth Round and had begun to amass supporters who believed he and Artis were innocent. One sent Dylan the book. He was moved by it and resolved to help Carter, declaring that “…the man’s philosophy and my philosophy were running down the same road.”

Sessions for Dylan’s next album began on July 14 at Columbia Recording Studios. Dylan and Levy co-wrote most of the material – including a plea for Rubin Carter’s exoneration called Hurricane. Despite initial traffic jams in the studio, a core band of Stoner, Wyeth and violinist Scarlet Rivera emerged. The album Desire was released the following January and reached Number 1 on the US charts and Number 3 in the UK.

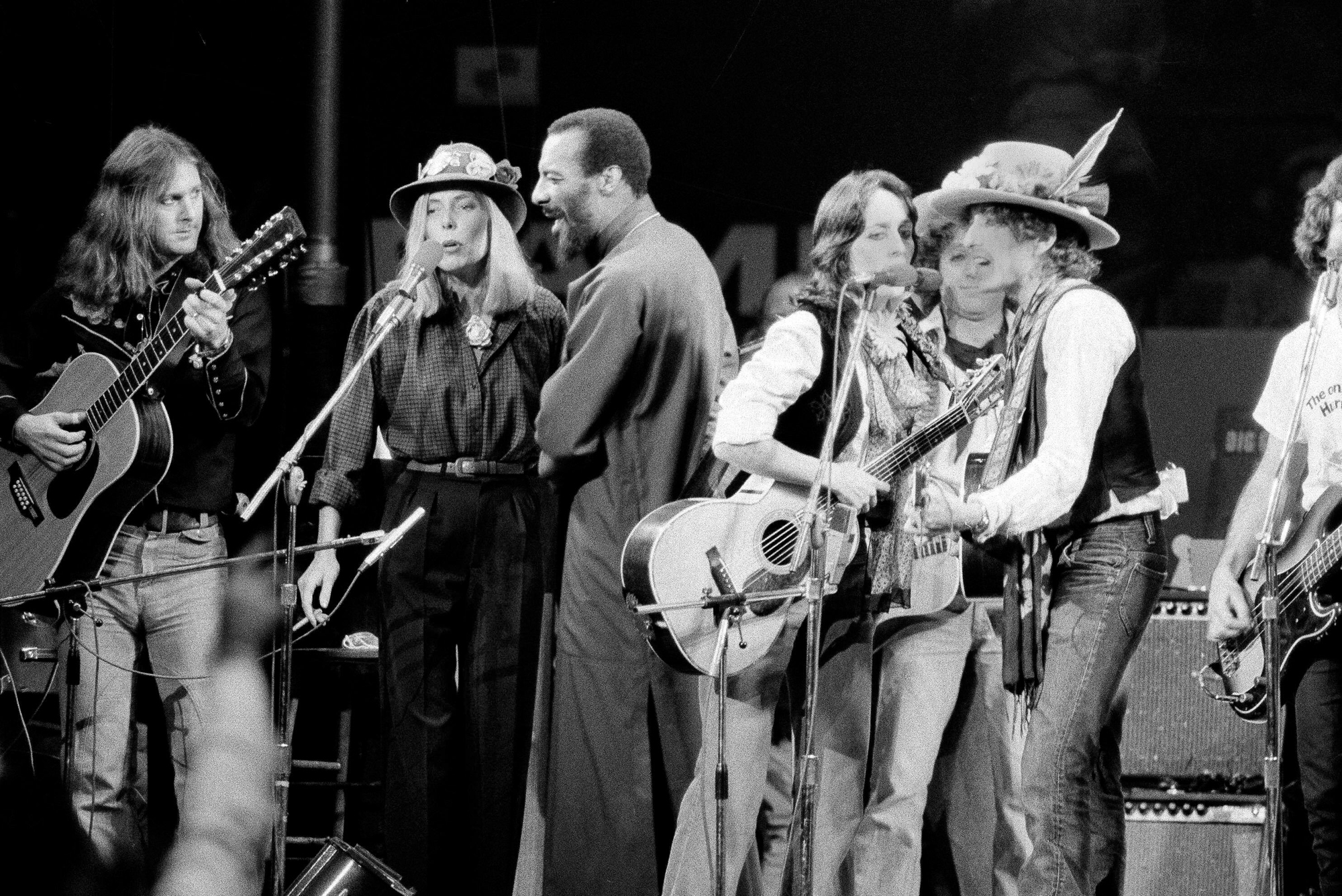

By October, the basic line-up for Dylan’s “travelling variety carnival-type show” was set in stone, a combination of established stars, Neuwirth’s Other Enders and strays: Joan Baez, McGuinn, Ramblin’ Jack, Blakley, Stoner, Wyeth, Rivera, Soles, T Bone, Ronson, Mansfield and drummer/percussionist Luther Rix. Neuwirth was master of ceremonies and Beat daddy Allen Ginsberg was road poet. Joni Mitchell would join up in November and Gordon Lightfoot, Arlo Guthrie, Richie Havens, Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko would sit in along the route. With all these humans coming on-and-off-stage, Jacques Levy would oversee transitions and lighting.

Dylan hired Duluth childhood pal Louie Kemp to manage the entire operation. Kemp had made a fortune with his seafood business and Dylan trusted him. “Bob said, ‘I don’t care if we make a profit as long as we break even,’” recalls Kemp. The singer added a rider: “‘As long as we’re going out, I wanna shoot a movie too.’ So we hired a movie crew.” Playwright and future movie star Sam Shepard was enlisted to write the screenplay. There was also a tour astrologer, herbalist, and the baggage handler was poet/Ginsberg companion Peter Orlovsky. Ratso Sloman became the embedded reporter. Dylan told Ratso he came up with the name ‘Rolling Thunder’ after hearing a series of booms in the sky.

Rehearsals that month were loose. “Dylan would start playing a song and the band would fall in behind him,” says David Mansfield. “There were no band directions. It was great training as an accompanist because he was so unpredictable. As we rehearsed more, the arrangements became finely honed. It was a band dynamic as opposed to a leader-and-musicians dynamic.”

While there were some excellent players in the Rolling Thunder band – particularly Mansfield and bassist Stoner – flexibility and a checked ego were more valued than virtuosity. By the end of October, everyone was ready. It was an audacious combination: musical tour, film shoot and political cause to free Hurricane Carter, with a legend at the helm. But as Dylan made clear to Kemp, the F-word was foremost in his thoughts: “I want the audiences and musicians to have fun.”

Thunder Road: (l-r) Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, Richi Havens, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan perform the finale of the The Rolling Thunder Revue

THE FIRST TWO SHOWS WERE IN PLYMOUTH, Massachusetts on October 30-31, 1975. It was historically symbolic as the location of Plymouth Colony, one of the earliest European settlements in what would be termed North America. Kemp chose the route. “I’d always found New England enchanting. I thought starting this magical mystery tour there as well as on Halloween amusing and apropos. We combined the pilgrims and the goblins.”

The area is also renowned for its breathtaking autumn scenery. “New England was beautiful,” remembers McGuinn. “It was in the fall and the leaves were turning. The trees looked like fire – orange and red and yellow. It was crisp and cold. We’d stop at these little theatres, do this four and a half hour show, jump on the bus and do it again.”

The band rode in a bus procured from Frank Zappa, dubbed ‘Phydeaux’. The film crew and others had a separate bus and Dylan had a camper to himself and invited guests. An advance team had been sent out to scout the gigs and distribute leaflets announcing the shows. Road manager and Beatles/Stones vet Chris O’Dell edited an in-house newsletter that disseminated news, gossip, in-jokes – and the location of the next gig. Ronee Blakley: “Our destinations were secret. We didn’t know our itinerary. We’d do a show and sometimes head straight to another place without knowing where.”

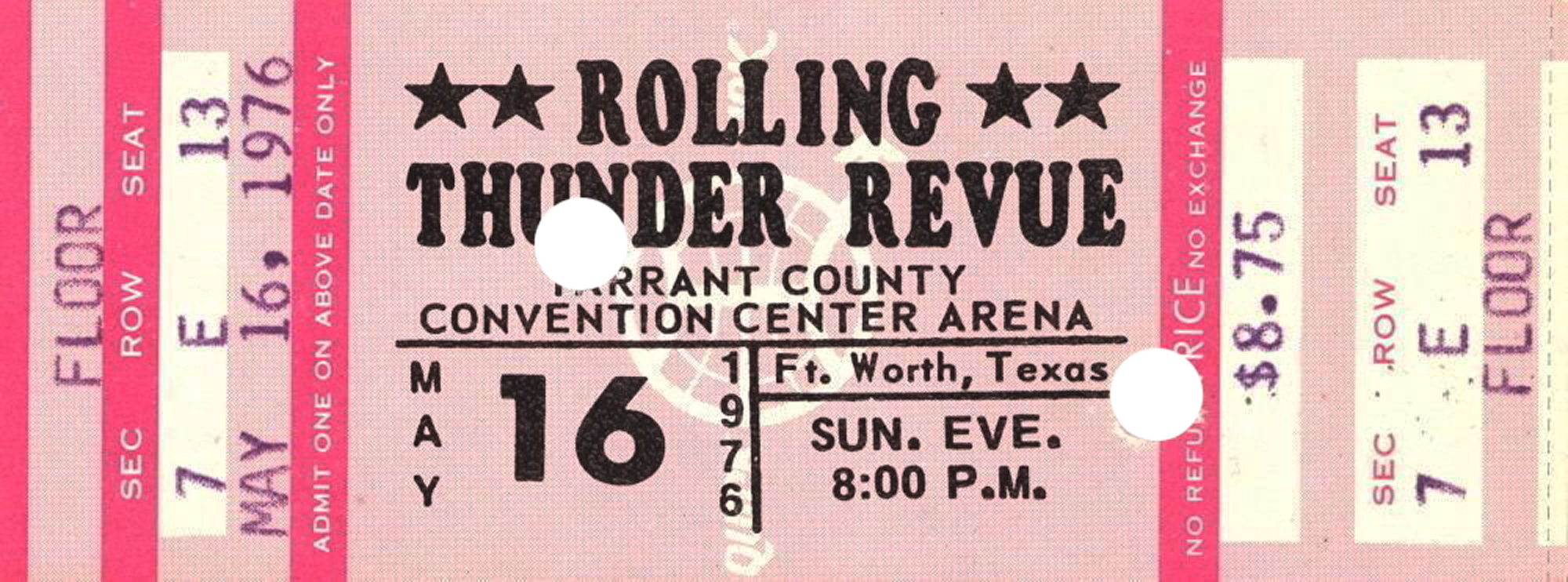

Shows would begin with an eclectic band set in which all the singer-songwriters took turns. Highlights included Stoner’s sleek rockabilly tunes; Blakley’s powerhouse vocals; T Bone’s rendition of Warren Zevon’s Werewolves Of London (before the author’s release); Ronson’s Is There Life On Mars? (not the Bowie song); McGuinn’s Eight Miles High; and Ramblin’ Jack’s masterclass in Folk 101. Then Dylan would materialise to the audience’s audible glee and perform a short set. After an intermission, two anonymous voices in harmony were heard in the dark. As the lights came up, the fans were ecstatic to recognise Baez and Dylan, who would perform four or five songs as a duo. Baez followed with her solo set, then Dylan solo acoustic, finishing with band.

The theatrical touches, like the Dylan/Baez lighting, were the work of Jacques Levy, with input from the star, and included Dylan’s whiteface make-up, a mask, an ever-present flower-bedecked gaucho hat and mysterious arm gestures (such as crossing his clenched fists during Isis). The latter gave rise to baffled gossip among onlookers, but Sloman explains them simply: “These were epic songs and Dylan was performing in character and dramatically gesticulating.”

Levy’s future-wife Claudia Carr Levy was there for the tour’s duration. “It was very romantic,” she says now. “The arc of the tour Bob had in his mind was going to be this drama. That’s when he started wearing whiteface. Jacques worked with him to deal with the way he moved on-stage. Bob is very graceful, he moves like a dancer.”

Since the 1967 film release of Dont Look Back had made public the friction between them, Dylan and Baez’s professional relationship had been considered as finished as their romantic one. But here they were, sharing a stage once more. “The audience went crazy,” says Claudia. “Here was Bob and Joan performing together again. It was very dramatic! Jacques was trying to keep this drama going and he lit it like a drama.” But there was humour as well. “At one gig, Bob and Joan came out dressed identically, both in hats and whiteface – you couldn’t tell who was who!”

“Our destinations were secret. We’d do a show and head straight to another place without knowing where.”

Ronee Blakley

THE MUSIC EVOLVED ORGANICALLY AS THE TOUR progressed, but for de facto bandleader Rob Stoner it was a leap in the dark. “I picked up the baton,” says the bassist. “If you listen to the bootlegs of our first show in Plymouth and you compare them to a show a few weeks later you’ll notice that all kinds of things were added – intros, endings, instrumental figures that complement the vocals. Much was accomplished by me staying up all night with cassettes of the rehearsal or gig.”

But the mercurial star could be a challenge. Stoner: “Bob was enamoured of arrangements that would stop and start, that would intentionally go out of tempo, like the bridge at the end of O Sister. Maggie’s Farm was another one. Romance In Durango. Every time the song stopped, I’d be sweatin’: Jesus – I hope everybody comes back in at the same place! There were no train wrecks, but there were a lotta close ones.”

According to Stoner, not everyone was musically indispensable. “There were entirely too many guitar players, man,” he says, chuckling. “You had 10 guys playin’ a fuckin’ G chord! But it looked good to have an army of guitar players up there.”

“Occasionally arrangements got cluttered,” says David Mansfield. “But most of these rhythm guitarists were also singer-songwriters or producers. They had a knack for staying out of the way, never elevating their own position at the expense of the arrangement. Mick Ronson was known as a guitar god, but he was a really good producer-arranger and he would never clutter up an arrangement for self-aggrandisement.”

By the middle of the tour, the RTR band were a well-oiled machine. The lion’s share of credit – according to everyone – was the ringmaster’s due. “Dylan was in great shape – probably the best I’ve ever seen him,” notes McGuinn. “His energy level was really up. His vocals were in tune and on time. He did trills. Like his vocal gymnastics on One More Cup Of Coffee – it’s hard to do.”

Stoner concurs: “I’ve never heard Bob’s chops as good as in the mid-to-late-’70s. He had amazing power, he conveyed a lot of emotion, his range was great – he could hold a note for a long time. As the main harmony singer, I’ll tell you the guy was great to sing with. He pushed me to not only stay with him because of his unpredictable phrasing, but to try and match his raw emotional power. When you have anything to do with him, you bring your best game.”

Dylan was also directing a feature film, with musicians doubling as actors, and friends and professional thespians like Harry Dean Stanton joining in. Bob portrayed a character named Renaldo and Sara Dylan played his beloved Clara. Despite Shepard’s work, the scenes were improvised based on concepts by Dylan and others (legend has it the musicians weren’t learning their lines). Fiction alternated with reality, including exchanges between Dylan and Baez that reflected back on their ’60s romance (Baez did the same on-stage with her autobiographical song Diamonds And Rust). “They’d shoot movie scenes before and after he went on-stage,” says Sloman. “It was amazing that he had the stamina to do all this.”

As the tour wended its way, small halls made way for the arenas Dylan had so deplored in ’74, the hike in takings needed to fund the movie and offset rising expenses. On December 7, the RTR played for prisoners, including Hurricane Carter, at the Clinton Correctional Institute in New Jersey. The following day was the Night Of The Hurricane at New York’s Madison Square Garden, a benefit for the boxer’s defence fund. With 30-odd shows under their belts (special commemorative belt buckles courtesy of Bob and Sara), the gang rested over the holidays.

Dylan had been in a good place, something remarked on by everyone. “Bob was very happy,” says Claudia Levy. “He was accessible and having a real good time.” Uncharacteristically garrulous on-stage, he repeatedly dedicated songs to friends and joked with fans. When one loudly requested Just Like A Woman, he responded with “What’s just like a woman? [There’s] nothing like a woman!” Dylan’s enthusiasm helped maintain the mood. “The spirit of camaraderie was very intense,” recalls Mansfield. Dylan had realised his dream of a “different” tour with “fun” for all – including himself. Things would soon change.

THE FIRST GIG OF THE ROLLING THUNDER restart began in Los Angeles on January 22, 1976, but was primarily a tour of the American South. While Ramblin’ Jack, Ginsberg, Joni and Ronee were all gone (with occasional return appearances by some) – and Texas country singer/humourist Kinky Friedman joined up – the line-up was otherwise the same, but the mood was not. A frustrated Sam Shepard had left after his movie script was discarded. David Mansfield: “It felt like we were trying to recapture what we did in ’75, with varying degrees of success.” The region may have had something to do with it. “The South wasn’t enamoured of Bob the same way the North-east was,” notes Claudia.

But it was Dylan’s personal life that was the biggest problem: his marriage was falling apart. The fun, accessible Bob was gone. “Bob’s interactions with the band were sometimes difficult,” says Mansfield. “He had a black cloud over his head – the band could feel that. And the music had a more aggressive, harder-edged sound than ’75.”

That sound is evident on the Hard Rain TV special and album that was filmed/recorded in Colorado at the end of the tour on May 23. Channelled anger can make for compelling art, and the music remained first-rate, yet that black cloud hovered throughout.

Claudia Levy recalls one night on leg two: “I was backstage and it hadn’t been a good performance. And Bob had a towel and he was wiping his face. There was something about the way that he was. And I said something about it being a really interesting performance. He looked at me and said, ‘Ya think so?’ And then he just walked away. Bob took a chair and moved it away from everybody and sat by himself. Nobody would talk to him and he didn’t want anybody near him.”

There were still some good times. “I remember singing I’m Proud To Be An Asshole From El Paso with Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell singing on either side of me wearing big sombreros,” says Kinky Friedman. “That was classic.” McGuinn recounts the troupe’s visit to swamp rocker Bobby Charles’s house in Louisiana. “He had this alligator on a platter in his hallway and kegs of beer. Beer and alligator for breakfast!”

The Rolling Thunder Revue ended in Salt Lake City on May 25. Bob and Kinky flew to Yelapa in Mexico to unwind. Kinky chuckles at the memory. “There was no first class. Bob was sitting next to a civilian – this woman. And she starts shouting, ‘I’m sitting next to Bob Dylan! I can’t believe it! I’m sitting next to Bob Dylan – I can’t believe it!’ And without missing a beat, Bob said: ‘Pinch yourself.’”

The four-hour film Renaldo & Clara was eventually released in 1978 to disparaging reviews. A combination dramatic art film, surreal documentary and rock concert, the New York Times called it “a film no one is likely to find altogether comprehensible.” (T Bone Burnett half-jokes that “Everybody was playing [variations of] Bob or Sara.”) It’s certainly not a mainstream movie, just as Tarantula was not a mainstream novel. “I made it for a specific group of people and myself, and that’s all,” Dylan told Jonathan Cott in 1978. “That’s how I wrote Blowin’ In The Wind and The Times They Are A-Changin’. They were written for a certain crowd of people and for certain artists. Who knew they were going to be big songs?”

Opinions of the film were mixed even among the participants. “It was misbegotten,” says Claudia Levy. “It was a good effort that didn’t coalesce. It lost the trajectory of what it was supposed to be.” Ratso Sloman, on the other hand, dug it. “While it may have been a little too long, I respect the ambition that went into it. It completely transcends the usual music documentary about a tour and raised huge issues about identity, fidelity and mortality.”

FOOTAGE SHOT FOR Renaldo & Clara can be seen in the forthcoming documentary Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. The long-awaited film will debut on Netflix globally in the next month or so. A veil of secrecy has prevented the few who’ve seen it from discussing it. As MOJO went to press, a lone announcement described it as “part documentary, part concert film, part fever dream”. We know many original participants were interviewed and that the concert footage of Dylan is rumoured to be extraordinary.

Meanwhile, a 14-CD companion box, Bob Dylan – The 1975 Live Recordings is due soon. As well as rehearsals and rarities, most of the discs capture entire Dylan sets, unlike 2002’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975 in which performances from four cities were cherrypicked. Sonically superior to the bootlegs in circulation, the recordings are thrilling evidence of Dylan and band’s relentless energy and commitment to the music night after night (dig the transformation of The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll from its topical folk origin to spitting-mad hard rocker on December 4 in Montreal). “As effortless as Dylan makes it seem, it’s not magic – you have to fuckin’ put in the work,” notes Ratso Sloman.

As well as giving Dylan a shot in the arm, Rolling Thunder boosted the careers of many of the tour’s other musicians. “It was an act of deep generosity by Bob [when] he opened his stage up to us,” says T Bone Burnett, pointing to the “collaborative nature” of the project. “Rolling Thunder taught me everything I needed to know to survive for 50 years in show business.”

Scarlet Rivera agrees: “I can draw a direct line from Bob to each of the many things I have accomplished both in my continued music career and personal evolution. He saw who I could be before I did.”

Forty-three years after the last clap of Rolling Thunder, its reputation as a singular tour lives on. Ratso: “It was an amazing cultural event that we’ll never see again.” Roger McGuinn: “My take on the whole thing was the music business had gone very bland and commercial in the mid-‘70s. It wasn’t like the excitement of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones and the ’60s we all had.” As a veteran of that era, ex-Byrd McGuinn would know. “There’s always a balance between art and commerce and commerce had taken over in the ’70s. Bob restored the art side of the balance.”

Today, Rolling Thunder still resonates powerfully. Dylan may not have been the first megastar to loathe the soulless barns that commercial success decrees, and he won’t be the last. But he created an alternative, however short-lived, for subsequent musicians to learn from. Ultimately, the spirit of the Rolling Thunder Revue informed the music and we’ll have the music forever.

This article originally appeared in Issue 307 of MOJO

Images: Getty