Mojo

FEATURE

A Change Is Gonna Come

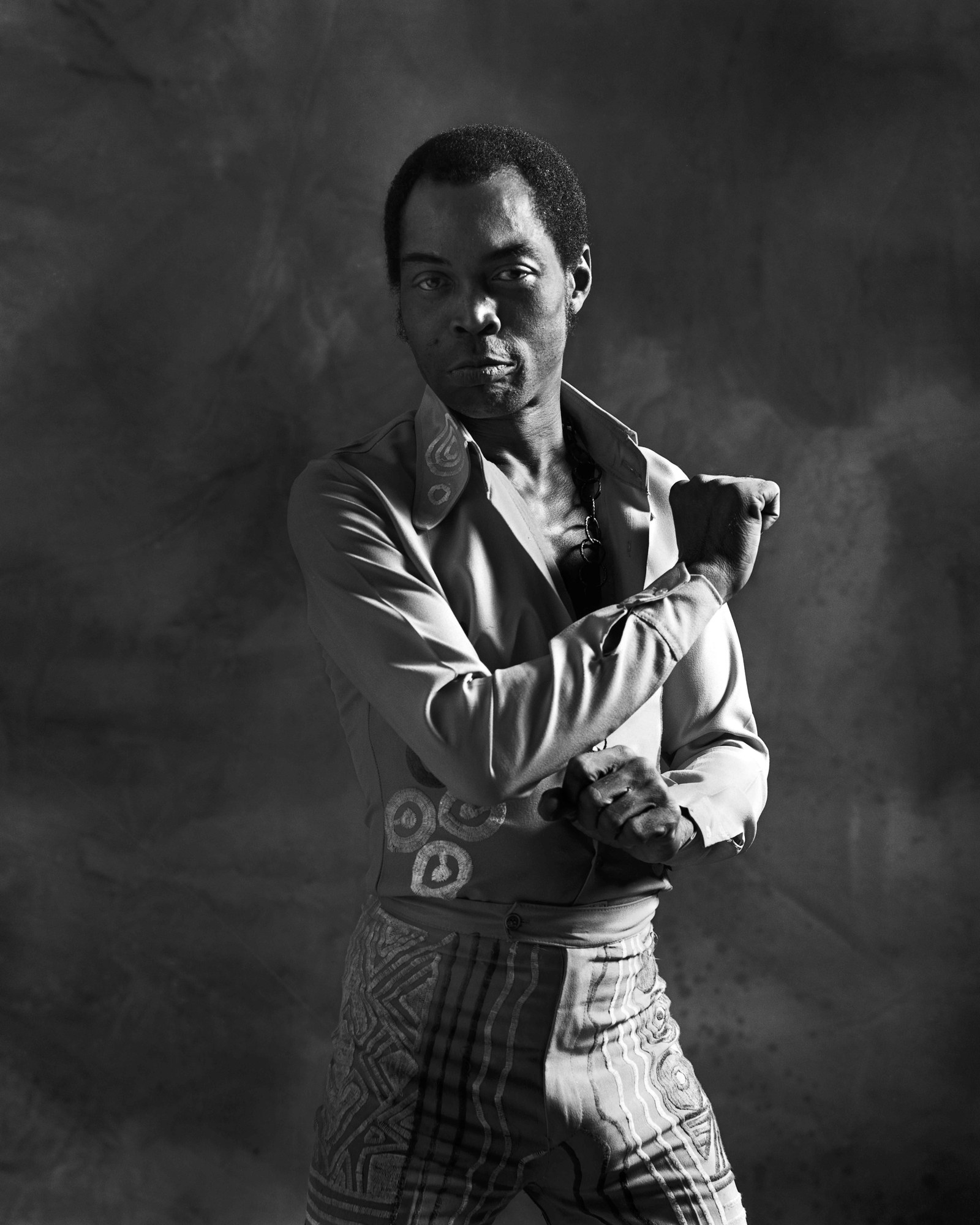

How did a middle class, prospective medical student rise from playing traditional highlife music to becoming Nigeria’s public enemy number one? In 2011 David Hutcheon spoke to those who knew him best and chronicles the radicalisation of Fela Kuti – Africa’s greatest and most revolutionary star…

Fela was a great father. If you got past his eccentricities and his peculiarities, you know… Once you got past them, he was a great guy. Even a lot of my siblings couldn’t cope with that.” Sitting in the lounge of a Dublin hotel, a chirpy Seun Kuti looks every bit his father’s son, and is happy to let anybody know what a sweet chap he was. This, of course, is not the man the world ever heard about.

By legend, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the progenitor of Afrobeat, whose name meant “He who carries death in his pouch”, was a philosopher-warrior – a mythical mix of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Leonidas of Sparta and Che Guevara – who took every beating dictators could hand out and came back for more; who single-handedly smoked more dope than the entire Rasta nation; whose simultaneous marriage to 26 (or was it 27?) women only boosted his outrageous sexual appetite; whose gigs lasted not hours but days. Was he really just a misunderstood family man?

Born in the Nigerian town of Abeokuta, 60 miles north of the then-capital, Lagos, in 1938, Kuti had a comfortably middle-class childhood: his father, Daudu, was an Anglican minister and teacher; his mother, Funmilayo, a progressive community leader, reputedly the first Nigerian woman to drive a car. Had Fela never been born, she would still be a chapter in West African history, but musicians who played with Kuti in his early days insist she was also among his most significant mentors.

Born in the Nigerian town of Abeokuta, 60 miles north of the then-capital, Lagos, in 1938, Kuti had a comfortably middle-class childhood: his father, Daudu, was an Anglican minister and teacher; his mother, Funmilayo, a progressive community leader, reputedly the first Nigerian woman to drive a car. Had Fela never been born, she would still be a chapter in West African history, but musicians who played with Kuti in his early days insist she was also among his most significant mentors.

“She was the number one activist in Nigeria,” says drummer Tony Allen, who joined Fela’s jazz quintet in 1964. “No other woman had reached her level in the culture. He took like his mother; she was very outspoken and never hid anything. Fela was like that.” Sax player Lekan Animashaun, who signed on in January 1965, credits Funmilayo with pointing Fela in the right direction musically: “She said, ‘If you want people to listen to your music you have to play something they can relate to easily.’ So when he wanted to become successful, he started composing songs that could appeal to the people, using a language they could readily recognise.”

Allen remembers Fela hanging around Lagos clubs in the late 1950s, when highlife was king. Among the important band-leaders playing this music, which owed a debt to both Cuba and the legacy of colonial brass bands, were ET Mensah, Cardinal Rex Lawson and Victor Olaiya. “I was working in the clubs then. I wasn’t playing drums but I was friends with Olaiya and his musicians, so I’d always be around. Fela would come and sing with them. Then one day he was gone.”

Like his brothers Koyu and Beko, and sister Dolupe, Fela had been sent to Britain to study medicine. Unlike them, he was set on doing something else. In August 1958, he enrolled at Trinity College of Music in London. By night, he was an aspiring professional trumpeter, hanging out in Soho’s modern jazz venues, a vibrant scene for immigrant jazzmen in the early ’60s. He befriended Joe Harriott, a Jamaican and the UK’s top alto player playing at the Metro Club on Tottenham Court Road. After leaving Britain, Fela would add sax to his weaponry.

The Africa Kuti returned to in 1963 was a very different continent to the one he had left: in those five years more than 20 countries, including Nigeria, had become independent. Fired by optimism for the future, and with a new band, the Koola Lobitos, Fela spent five years playing a unique fusion of highlife and jazz, recording over a dozen singles – including flag-wavers Nigerian Independence and Viva Nigeria – and a handful of albums. Yet, for the last time in his life, he couldn’t get arrested.

“We would never play highlife the normal way,” says Allen. “Those that did had an audience. It was tough for people to accommodate what we did, it sounded crazy to them. It took them a long time to catch up.”

The African crowds were instead turning to American soul, and the first to cash in was Geraldo Pino. Today seen as more Arthur Conley than Otis Redding, Pino is still a crucial influence on Afrobeat. Quoted in Carlos Moore’s Fela: This Bitch Of A Life, Kuti made his awe clear after witnessing the Sierra Leonean live in 1966: “What worried me was that he was going to come back again to Nigeria. I’d seen the impact this motherfucker had in Lagos. He had everyone in his pocket… there wasn’t shit I could do.” For a married man with young children to feed, the situation was desperate. Whatever American lightning Pino harnessed, Kuti wanted a part of it. When the opportunity to tour the States came up, he didn’t think twice.

“Fela said he couldn’t be a great man when people in his country were poor.”

Lekan Animashaun

The trip was a financial disaster, but witnessing the civil rights struggle awakened something in Fela. Based in Sunset Boulevard’s Citadel d’Haiti club, run by Bernie Hamilton (future Captain Dobey in Starsky And Hutch, brother of Chico), the band were renamed first Nigeria 70, then Africa 70, as Kuti’s interest in his continent’s cultural heritage grew, thanks to the guidance of Black Panther friends such as Sandra Isidore. The irony of a Nigerian having to go to the new world to learn about African history impressed him deeply.

“In those nine months, Fela and some of us were exposed to things that were being kept from us in Africa,” says Animashaun. “I’m talking about history books not available in Nigeria. When we got back home from that tour, Fela said he couldn’t be a great man when people in his country were poor.”

The decision to Africanise his music, turning to tribal beats and call-and-response chants, meant an increased prominence for Allen, who had a wealth of knowledge of African rhythms. “In America, we were advised to keep it simple to make money. When the music became simple and trancey, with a good groove, that’s when people became fans, that’s when everything became like an explosion.”

The drummer bristles at any suggestion that Kuti was copying the funk template developed by James Brown, who had already made two trips to West Africa, in 1966 and 1968. “Have you ever heard anybody play like me? James Brown’s drummer? James Brown’s two drummers? No.”

And Fred Wesley, Brown’s trombonist at the time, adds: “Fela got a lot from James, but what’s not as obvious is what James got from Africa – the hard drive. He’d heard music there that undoubtedly influenced him. It was the same beat, sure, the same chords, but the drive was African. There Was A Time was influenced by Africa, and that became a big hit for us in Africa.”

The Africa 70 fled America before immigration officials could ask them about their long-expired visas and non-existent work permits. “We were happy to go home,” says Animashaun. “In America, we saw the great difference between the black and the white. I realised things there were a fantasy, the black people had little or no rights, they were bullied. In many aspects of life, you saw black people wanting. From then, the changes started coming. Fela was getting revolutionary in his music and his lyrics.”

Over the next few years a series of singles and albums were released combining sex talk (Na Poi, Lady), the pan-Africanism brought back from the US (My Lady Frustration) and social observation (Monday Morning In Lagos, Gentleman). Finally, Fela was a star and the seven-hour Africa 70 shows at his Shrine nightclub were the hottest tickets in town. As word grew, there were collaborations with Ginger Baker (Stratavarious) and run-ins with Paul McCartney. Yet not even his unpopularity among Nigeria’s polite society suggested Kuti was about to become public enemy number one.

Everything changed in 1974. In April, the band’s compound in Surulere, then known simply as Fela’s House or the Africa 70 Organisation, was raided for drugs. “I had nothing to fear,” he told Carlos Moore. “I wasn’t even thinking they could have something against me. I was just preaching revolution for Africa, you know. I didn’t know they were planning against me, man.”

Fifty policeman arrived, found marijuana and took the male residents to the Nigerian police station Alagbon Close. Kuti spent more than a week in prison before returning home, only to be promptly busted again. This time, he was stuck in a cell until he could give a stool sample for analysis. The result was negative. On release, Kuti erected a 10ft, electrified, barbed-wire fence around his home, as if expecting further trouble. He also wrote the satirical Expensive Shit, the first in a sequence of songs that recorded his dealings with the agencies of oppression. The tension increased with what became known as the Kalakuta Show, in November, which began when a man came looking for his sister.

“It started as a joke,” says alto sax player Adedimeji ‘Showboy’ Fagbemi, who had recently joined Fela’s crew. “He was just passing and saw somebody who looked like his kid sister, who had been missing for two months. He came in, found out it was her and started beating her up.” It was a rule that women were not hit in Fela’s house. The brother was attacked and thrown out.

The girl’s mother visited next, but when her daughter refused to leave Kuti said there was nothing he could do. “Fela told her he didn’t write ‘Vacancy’ in front of his house, that his gate was open to everybody,” Showboy continues. “She left and we thought that was it.”

Nobody knew, however, that the girl’s father was a police commissioner. “On Friday night we went to the Shrine to play. By the time we finished on Saturday morning, the police had surrounded the compound, but they didn’t hassle us, didn’t make any arrests. They were waiting for reinforcements. Around 1pm, we heard some sirens coming towards us. Before we knew it, 500 cops with cutlasses, hammers and other weapons were at the fence. They started chopping the wire, then they shot about 300 canisters of tear gas and attacked. I was standing next to Fela, watching them.

“They took all of us to the police office, but the man in charge said he couldn’t hold us because we were too many. So they took us to Alagbon Close and put us all in Kalakuta [ruffian] cell.”

“They threw tear-gas and beat the shit outta us,” Kuti told Moore. “I was cut, bleeding profusely. Couldn’t even stand up or walk.”

“Fela was beaten,” continues Showboy, “They broke his head, broke his arm. His mother followed the police and insisted he was taken to hospital and not locked up. She went to a judge and got him bail on Monday morning. We stayed in jail for two weeks. When we got home, Fela had renamed the compound Kalakuta Republic.”

“500 cops with cutlasses, hammers and other weapons shot about 300 canisters of tear gas and attacked.”

Adedimeji ‘Showboy’ Fagbemi

The first half of 1975 saw the persecution continue, with Fela’s men regularly harassed. The bandleader, however, seemed to absorb the attacks, transforming himself into the Kuti of myth, unbowed, righteous and cocksure, berating his audience and mocking his enemies, revelling in his notoriety and status. His mischievous creativity came in inverse proportion to his popularity among the Establishment, and in 1974-76, he was on a roll.

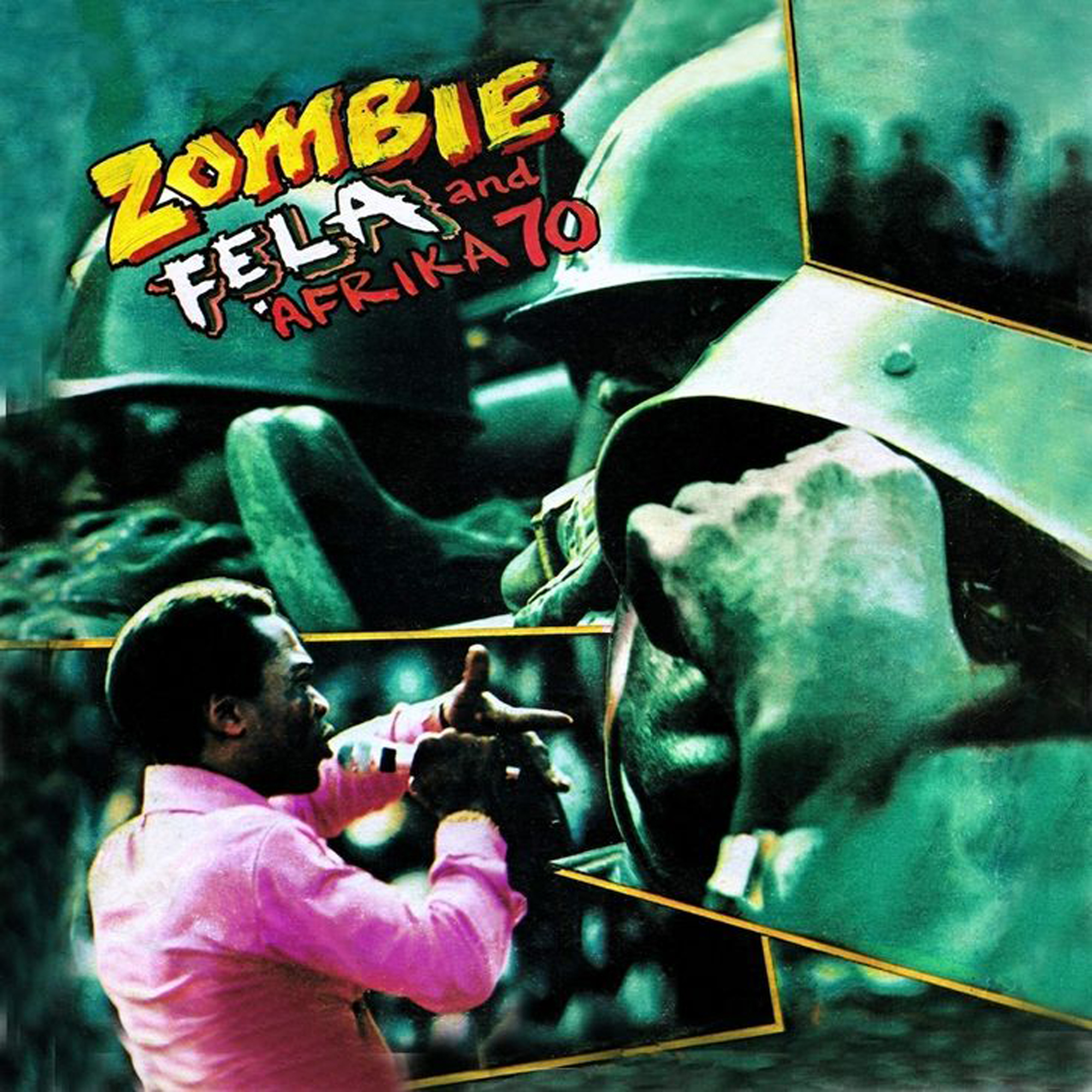

After the Expensive Shit LP came Alagbon Close, Everything Scatter, Kalakuta Show, with its sleeve featuring a battered Kuti, and, at the end of 1976, his 13th album in two years and his most successful to date, Zombie. If the sleeve, which crudely imposed a tiny Fela in front of a wall of helmets, wasn’t explicit enough, the lyrics – “Zombie no go go, unless you tell him to go/Zombie no go stop unless you tell him to stop” – would prove too much for his enemies.

In January 1977, as Nigeria celebrated the FESTAC festival of black and African culture, Fela fumed about corruption from the sidelines. The Shrine did a roaring trade, however, with Stevie Wonder, Sun Ra and Archie Shepp all making the trek to Fela’s to meet and play with the self-proclaimed ‘Black President’.

On February 18, in excess of 1,000 soldiers attacked Kalakuta. In This Bitch Of A Life, Moore interviews a number of Kuti’s queens, and their harrowing recollections of the attack make grim reading. Beko was left in a wheelchair; Funmilayo, then 78, was thrown from a window and would later die of her injuries; Fela only escaped death through the intervention of an army officer who told his charges to stop beating him. The compound was burnt to the ground, along with a clinic and recording studio. Two months later, a government inquiry found that Kalakuta had been destroyed by “an unknown soldier”.

If the human toll of the attack was awful, the financial implications left Kuti in dire straits. His followers had no homes, his band had nowhere to play, no instruments and no studio, his queens were traumatised and treated worse than prostitutes, and he was in self-imposed exile in Ghana for his own safety. Dates in Germany in 1978 saw many of the Africa 70 quit, including Allen. “He treated me like a child and I ran out of patience,” says the drummer. Kuti’s best years were behind him.

The next decade saw Kuti’s fame grow, yet success came at a price. The outside world caught up with Afrobeat, but didn’t always like what it saw or heard. The new band, Egypt 80, led by Animashaun, still produced fine albums, but their shows could mesmerise – his late-night set at Glastonbury 1984, captured by the BBC – or disappoint – Brixton Academy, 1983 – thanks to Kuti’s refusal to play anything crowds already knew. If you want to hear Zombie again, buy the LP.

Then there was his polygamy, even misogyny. Seun, the son of one of the wives he married in 1978, points the finger at western attitudes: “In Kalakuta, after Fela the most important people in the house, the most powerful, were the women. So he actually thought of them as very strong politically. Now look at Bill Clinton: he was married and sneaking into the Oval Office to get a blow job. If Clinton was an African, he would have been getting a blow job in his house, he could have been chilling with the kids and his wife, his second wife.”

Meanwhile, the Nigerian government kept on Kuti’s back, keeping him in court throughout the first half of the 1980s. A 1984 tour of America proved to be eldest son Femi’s big break when he had to stand in for his father, imprisoned on trumped-up smuggling charges. Yet even he would soon depart.

Fela had discovered an Egypt-centric African spirituality, which left him out of step with even the most sympathetic ears in the western world. In 1984, he told the NME’s Len Brown that Queen Elizabeth had come to Egypt in 1470 to steal power from the Yoruba people, then the explorer Mungo Park brought back a witchpot to Buckingham Palace, thus stealing African technology for Europe.

“I’m giving you fact whether people like to know it or not. Science uses words like theory to debase spiritual happenings.” Fatally, that was an attitude he took towards the arrival of a new disease in Africa.

His death in August 1997, of complications brought on by Aids, encouraged more than a million people onto the streets of Lagos. “My father was cool,” says Femi in a manner that brooks no disagreement. “He was hip, he stood by his beliefs and confronted the government. People pretend they are Fela’s guys, but when the problems come, they chicken out. He never ran, he was the only one standing.

This article originally appeared in Issue 210 of MOJO