Mojo

FEATURE

Just Say No

The most significant underground band of the past 40 years, Fugazi have remained true to their libertarian DIY punk principals, refusing $10 million label deals and prizing kinship above commerce. “Nothing should get in the way of the music,” Ian MacKaye told Paul Brannigan in 2011.

In the summer of 1981, after graduating from high school, Ian MacKaye moved out of his parents’ Washington DC home and found a place of his own. There were practical considerations underpinning the teenager’s declaration of independence: his band, Minor Threat, were looking for a regular rehearsal space, he needed an office for Dischord, the fledgling record label he and Minor Threat drummer Jeff Nelson had set up to document the nascent DC punk scene, and his crew required a safe haven to socialise now that their regular hang-outs in the Georgetown district had become over-run with college jocks and marines intent upon meting out attitude adjustment to local punks.

With prohibitive prices ruling out apartments in the capital’s more fashionable zip codes, MacKaye and Nelson opted to rent a property across the Potomac River, moving into a four-bedroom bungalow in Arlington, Virginia with three fellow musicians.

Life at Dischord House, as the property became known, was soundtracked by hardcore punk, a searing, scorched-earth manifesto created by, for and about America’s angry, alienated youth. In DC, through bands such as Minor Threat, Faith, Scream and State Of Alert, the scene acquired definition and a sense of uncompromised righteous purpose. Dischord valued community above commerce, eschewing legal contracts, selling its releases at affordable prices and splitting all profits equally between artists and label.

A hive of industry, the Dischord House saw its basement serve as a communal rehearsal space, while a small room off the kitchen became the record label office. When their bands weren’t practising, MacKaye and his friends devoted their free time to cutting and folding record sleeves, designing flyers, penning columns for fanzines and writing letters to record-store owners, promoters and college radio DJs nationwide, as part of a collective mission to spread the hardcore gospel. That 31 years on from its inception, Dischord remains engaged, involved and connected to the community and city it serves is no small achievement.

“From the start people told us that the way we operated wouldn’t work, couldn’t work,” says MacKaye flatly. “Well, guess what? It worked.”

“Our point was never to smash the system, our point was to make our own world.”

Ian MacKaye

Labour Day may be a statutory federal holiday throughout the United States, but Ian MacKaye works to his own schedule. Attired in a logo-free dark blue T-shirt and capacious shorts, Dischord’s captain of industry swings by MOJO’s Georgetown hotel at 10am, ready for a full day’s shift at his HQ. Often portrayed as an austere, intense character, in person the 49-year-old musician is fine company, blessed with a dry wit, a disarmingly direct conversational style, a boundless enthusiasm for music, and no little charm. Nudging his 2000 Honda Odyssey through picturesque streets, we cross the state line before arriving on a nondescript suburban street where, behind a chain-link fence, a small red brick bungalow with a slate grey roof nestles amid verdant shrubbery. Immortalised when Minor Threat posed upon its front porch for the cover of their final single, Salad Days, this is Dischord House.

Though he no longer lives here (he moved back into the District of Columbia in 2002), MacKaye’s life is documented by almost every square foot of the property. There are framed flyers and band photographs on every wall and boxes of vinyl stacked from floor to ceiling. MacKaye’s three-decades old skateboard and guitar amps are in the basement (where he and his partner, Amy Farina, still rehearse as The Evens) and his office walls are lined with Dischord record sleeves. In a second office upstairs his Minor Threat tour diaries share shelf-space with Fugazi master tapes, a row of MOJO magazines he started reading while laid up in a Sydney hospital with a collapsed lung in 1996, and hundreds of DAT cassettes documenting almost every live show Fugazi played, from their first gig at DC’s Wilson Centre on September 3, 1987 to the triptych of shows at London’s Kentish Town Forum with which the band signed off from live work in November 2002.

Officially, Fugazi are still on ‘indefinite hiatus’, yet the business of the band remains constant and demanding: for the past year, MacKaye has been engaged in digitising and cataloguing some 750 live recordings which will be made available for download – 100 shows at a time – as part of the Fugazi Live Series archive on the Dischord website in the coming months. In keeping with the label’s low-pricing policy, most sets will retail for $6, though fans will also have the option of paying anything from $1 to $100 for each recording, provided they write a note explaining their own personal pricing plan. The concept tickles MacKaye’s bandmates. Vocalist/guitarist Guy Picciotto and drummer Brendan Canty have also made the trip out to Dischord House this afternoon (bassist Joe Lally, currently on a solo tour in Japan, speaks via Skype) and watch as he runs through a demonstration of a beta version of the website on his laptop, discussing the photos and flyers appended to almost every entry. It’s an incredible albeit mind-boggling resource.

“We confuse people, because we don’t play by the rules,” MacKaye smiles. “The rules are dictated by an industry that we’re not a part of. I feel like this band defies definition. We’re kind of a freak show in a way.”

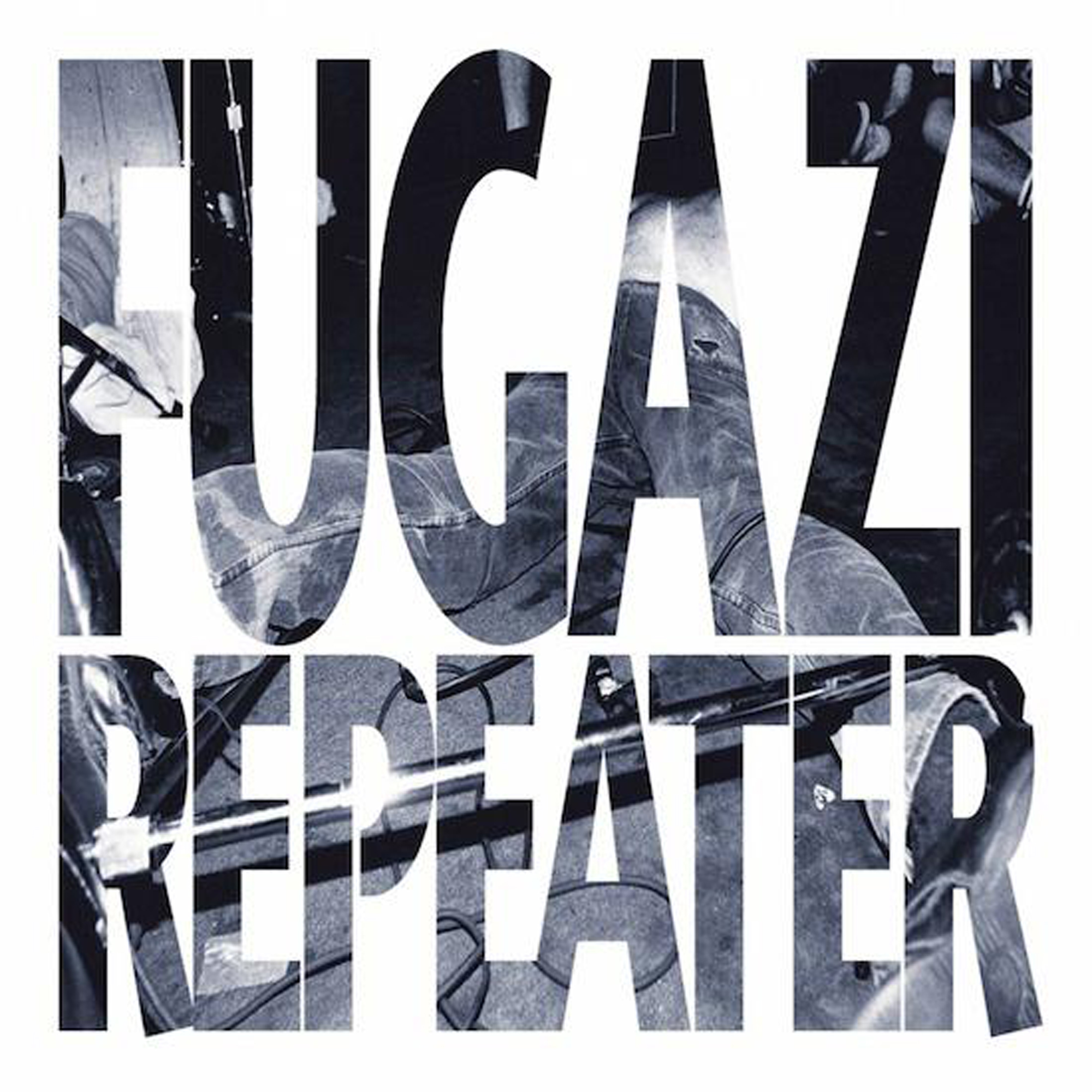

“Revolution is not the uprising against pre-existing order, but the setting up of a new order contradictory to the traditional one” runs a quote on the cassette version of Fugazi’s 1990 album Repeater. Lifted from Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset’s 1929 text La rebelión de las masas (The Revolt Of The Masses) these words offer an insight into Fugazi’s modus operandi since their inception in 1986. The band have never had a manager, a lawyer, a booking agent or road crew. They have never made a video, don’t sell merchandise, will only play all-ages shows, insist upon a $5 ticket price at gigs, and politely shun the attention of all facets of the corporate music industry. That this ethical code is considered to be such a maverick stance within that industry bemuses and irks the quartet.

“The central aspect of the way we present ourselves was based on the idea that this is about the music,” sighs MacKaye. “That’s the point: the music, the music, the music. And nothing should get in the way of the music. We came out of punk, and our point was never to smash the system, our point was to make our own world: just leave us alone, and let us do our thing.”

When the origins of the American hardcore punk scene are debated, East Coast punks cite the release of Bad Brains’ breathless 1980 Pay To Cum single as hardcore’s Year Zero: West Coast punks point out that Middle Class’s full-tilt Out Of Vogue EP predates the DC rasta-punks’ debut by two full years. Few, though, would argue against Minor Threat’s status as the definitive hardcore band. MacKaye’s band blazed with an incandescent fury which left all who saw them indelibly marked: no band did more to foster a sense of community in the punk scene and break down the invisible wall between ‘artist’ and ‘audience’. Nonetheless, by the summer of 1983, MacKaye was thoroughly sick of both the broader punk rock scene – with its attendant macho violence and bigotry and formulaic screeds of empty rhetoric – and his own place within it, as internecine arguments on questions of materialism, ethics and aspirations tore his band apart. After Minor Threat’s dissolution that autumn, it took the emergence of Picciotto and Canty’s Rites Of Spring one year later to re-ignite MacKaye’s passion for punk. Rites Of Spring sang of love, loss, wasted potential and spiritual rebirth, their off-kilter compositions stripping away hardcore’s machismo in order to expose its heart. Their emotive, empowering songs saw MacKaye reconnect with punk’s potential.

“It was like, ‘We’re not going to shut down your punk, have your punk’,” he recalls. “We’re going to have our own punk.”

In August 1986, MacKaye began jamming at Dischord House with Lally, a genial metalhead from Rockville, Maryland, whose discovery of punk’s “liberating” mindset had inspired him to swap a promising career with NASA to roadie for Dischord favourites Beefeater the previous summer. The pair had bonded over a shared affinity for The Obsessed, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix and The Stooges, and MacKaye pitched his new friend the idea of starting a project which married the unfettered righteous fury of MC5 with the soul and pulse of dub reggae. Starting a new band was not on MacKaye’s mind – this was simply a project for self-expression – but when Canty and Picciotto sat in with the duo at rehearsals, the chemistry between the four was evident.

With its title taken from US military slang for a fucked-up situation, the quartet’s eponymous debut EP, released on Dischord in November 1988, travelled beyond hardcore’s hackneyed musical framework, marrying taut, gridlocked guitars, rolling dub bass lines and shifting art-rock rhythms with two starkly contrasting voices – MacKaye all feral, vein-popping indignation, Picciotto offering a more feminine, abstract, atmospheric counterpoint. A second EP, Margin Walker, recorded in London in December at the end of a gruelling Europe tour which saw the quartet play 78 shows in 90 days without a record behind them, was more abstract, but it was the release of the band’s first full-length album, Repeater, in 1990 which marked Fugazi out as the most inventive, provocative and idiosyncratic collective within the underground punk community.

The most open-hearted declaration of independence since Gang Of Four’s Entertainment!, it articulated the seething frustration felt by a forgotten and marginalised American underclass and simultaneously laid out a manifesto for independent thought and deeds. “You say I need a job, I’ve got my own business,” sang MacKaye on the dizzying, scathing title track. “You want to know what I do? None of your fucking business.”

Back home in DC for Christmas after spending more than 200 days on the road in 1990, Ian MacKaye received a visitor at Dischord House. A familiar face from the DC hardcore scene, former Scream drummer Dave Grohl was back in town with a cassette of mixes of material that his new band Nirvana had been working on. Ever encouraging, MacKaye asked Grohl to play something for him.

“So he played a rough mix of… Teen Spirit,” MacKaye recalls. “I said, Wow, that is a fucking good song. That’s going to be a hit. Repeater had sold maybe 200,000 or 250,000 copies and at the time Nirvana had sold about 40,000 to 50,000 copies of Bleach, so when I said this would be popular I was thinking it could sell like maybe, 80 to 100,000 copies. I didn’t mean it like a hit in the Top 10, just a hit within our filthy mass of punks.”

“Nirvana got into bed with the devil and I think the industry was pleased.”

Ian MacKaye

As the Pentagon-authorised bombing of Baghdad began, initiating America’s most sustained armed conflict since the Vietnam war, the new year found Fugazi ensconced in Inner Ear studio in Arlington, toiling on their second album. Working without a producer for the first time, the band found themselves frustrated by their inability to commit to tape the raw aggression of songs they’d been honing for months on the road, and no one band member was prepared to lead the session: “We were feeling fucking fried,” admits Picciotto, “and we were making a record at a time when we should have been taking a break.” For all their discomfort, 1991’s Steady Diet Of Nothing was another landmark recording. The band’s most experimental and explicitly political album to date, it cast unforgiving eyes over George Bush’s America and offered a caustic dissection of a nation at war both internally and beyond its borders. Reclamation dealt with reproductive rights, Dear Justice Letter rang with desperate cries from the neglected margins of society and the aching Long Division offered a pained vision of crumbling relationships, both personal and political. Perhaps inevitably, given the social climate, it was the stark dread of Nice New Outfit and the activist call-to-arms Keep Your Eyes Open, anti-war songs both, which resonated most strongly.

In September ’91, two months after the album’s release, Fugazi toured Australia for the first time. In every club, every shop, every restaurant they visited, they found their trip soundtracked by a single song, the same song Dave Grohl had played for MacKaye at Dischord House the previous year: Smells Like Teen Spirit.

In the wake of the massive success of the recently released Nevermind, the quest for the ‘new Nirvana’ began in earnest. Major label A&R men descended upon America’s most fecund ‘alternative’ scenes – Seattle, Chicago, New York, DC – to cream off the most promising, or most commercially viable acts. DC bands Shudder To Think, Jawbox and Girls Against Boys were signed to major deals, while longtime Fugazi peers such as The Jesus Lizard, Butthole Surfers and Dinosaur Jr exited the underground. None prospered. With rock’s new poster boys Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder constantly namechecking Fugazi in interviews, the band were soon approached. MacKaye recalls a conversation he had with a representative of Atlantic Records in the early ’90s: he told the lady that Fugazi wanted $5 million and an assurance of complete creative control before they would consider signing to the label. After a moment’s silence on the line came the strained enquiry “Is that your final offer?”

“No,” MacKaye said. “Make it $10 million.”

“It was never a consideration,” he says. “Control was what we most dearly valued, and we knew that once we got into that, it’d be compromised. Once you’re an object of investment, people will do everything they can to maximise their returns. You can resist it, but it doesn’t make a difference. When you think about it, that term The Year That Punk Broke has an ironic double meaning. In some ways 1991 was the year that broke punk.

“The way the music industry works, they seek the fertile ground, they rape the ground and then they move on: they don’t take care of the soil at all, they don’t care. It was a very dark time in many ways for music. We were just watching people get chewed up.”

“I would never trade what we had for what Nirvana had in a million years,” adds Brendan Canty. “They had too much fucking misery in their lives. We got that there was a big trade-off in all that business, it was just a freak show. And it ultimately killed them. They got in bed with the devil and I think the industry was pleased as punch the way it all turned out. Now they have a dead icon to work with.”

It would be foolish to pretend that Nevermind’s success had no impact upon Fugazi. With their name a byword for integrity, independence and innovation, pre-orders for the band’s 1993 album In On The Kill Taker were the largest in Dischord history and the venues they were playing almost doubled in size. Canty recalls more “jocks and assholes” appearing at shows, and remembers feeling “insecure” about Fugazi’s ability to connect in larger rooms: MacKaye points to a ludicrous logistical problem whereby health and safety requirements in more traditional rock’n’roll venues led to a situation where installing a crowd safety barrier at one show meant his band had to pay out more money than they earned from the gig itself.

Fugazi’s response to the MTV-driven ‘alternative rock revolution’ was to step away from the noise and confusion. Save for a short South American tour and a handful of benefit shows in their hometown, the band took 1994 off. When they returned in ’95 with the more oblique Red Medicine album, the tumult had died down. Two more albums, ’98’s End Hits and 2001’s superb The Argument followed, while 1999’s Instrument, a visual collaboration with film-maker and longtime friend Jem Cohen, gave an intimate insight into their inner workings. Then, following 2002’s European tour, came the announcement that the band were to take their ‘indefinite’ break.

As MacKaye explains it, life circumstances began to make Fugazi’s traditional working practices harder to sustain: parents got sick and died, relationships expired, children were born. Band members had always committed to Fugazi 100 per cent – they practised five hours per day, five times a week when not on tour – and to step back and commit less seemed wrong. And so Fugazi simply stopped.

Since 2002, all four members of the band have continued making music. MacKaye has The Evens, Picciotto toured and recorded with the late Vic Chestnutt and produced records for The Gossip and Blonde Redhead, Lally has recorded three solo albums and released two more with ex and current Red Hot Chili Peppers guitarists John Frusciante and Josh Klinghoffer as Ataxia, while Canty has recorded TV soundtracks, played with Bob Mould and made films for Wilco and Eddie Vedder, among others. But all four men bristle when asked to pin down Fugazi’s own future in specific terms. Asked what Fugazi means to him in 2011, Picciotto, who admits to feeling “shocked” and “disorientated” when the band stopped playing together, pauses for a full 30 seconds before answering.

“I don’t know how to answer the question really,” he says finally. “Asking me what the band is to me is like asking me how I feel about breathing oxygen in the world. The music, the relationships, that’s just part of the environment that I’m in: the band is an ongoing thing. I mean, The Beatles broke up, but those guys could never leave The Beatles. I think I share, personally, that idea that there needs to be a coherent bracketing to this, but it doesn’t really make any sense: this is my life.”

Ever thoughtful, Ian MacKaye’s brow furrows as the question is placed to him.

“We may never play again,” he says, “Or we may play a lot of shows. I have no idea, and it doesn’t matter. Our relationships and our lives tower over people’s needs to have a nice tidy package.

This article originally appeared in Issue 217 of MOJO