Mojo

FEATURE

Tougher Than Leather

Judas Priest were forged in the industrial grime of the West Midlands. British Steel apprentice Glenn Tipton and self-professed “stately homo of heavy metal” Rob Halford reveal how S&M and Elkie Brooks helped shape a genre. “Leather is primordial,” learned Roy Wilkinson in 2014.

Judas Priest (l-r) bassist Ian Hill, guitarist Glenn Tipton, lead singer Rob Halford, guitarist K.K. Downing and drummer Dave Holland in Detroit, Michigan, 1984

THE QUEEN ASKED ME, ‘WHY IS HEAVY METAL so loud?’” recalls Judas Priest frontman Rob Halford, sitting in a comfy armchair high up on the 35th floor of Sony’s Manhattan headquarters. “I said, It’s so you can bang your head, Your Majesty.”

Halford met the Queen at Buckingham Palace in 2005, at an event celebrating British music. Upon his arrival, Halford had made a new friend – a showbusiness fixture with a voice almost as striking as his own multi-octave air-raid siren.

“There was one invite per person,” says Halford. “So I’m sat there by myself in this big room at Buckingham Palace, looking at Brian May and Bruce [Dickinson] from [Iron] Maiden and all these classical musicians – all these great stars, and I’m sat there on my tod. Then I see Cilla Black standing there by herself. I couldn’t believe it. So I go over – All right, Cilla?”

Rob Halford’s singing voice is a piercing holler fit to catalyse fear, fight or flight and has been ringing out since he started fronting Judas Priest in 1973. But as he sits placidly in the record company HQ, his speaking voice is the opposite of vocal terror – gentle Midlands tones at once dolorous and friendly, tinged with that burr of permanent puzzlement that goes with a Brummie accent. As soon as he opens his mouth his fistfuls of rings and shaven, tattooed head take on a different aspect, no longer some Mad Max-style malefactor ready to smash down your door, rather a biker with a heart of gold, stopping to solicitously help old ladies cross the road. Halford is now 63 and lives between Phoenix, Arizona and his native Midlands.

As he talks to MOJO (in 2014) the new Judas Priest album, Redeemer Of Souls, is about to enter the US chart at Number 6, the band’s best ever placing in America. To mark its release they were driven through New York City in an open-top Cadillac, escorted by a thunderous squadron of around 30 motorbikes. But, despite his globe-spanning existence and decades in rock, Halford talks of May and Dickinson as if they’re strange alien beings. Cilla Black is somehow a more natural chum.

“So, there I was with Cilla,” he continues. “We were joined at the hip for the rest of the night. An equerry came over and told us Her Majesty was going to come over. I did the wrong thing – putting my hand out to shake her hand, which you’re not meant to do. Cilla give me a glance… But Her Majesty graciously shook my hand. I’ve always felt that I have two mothers – because I love the royal family. To meet [the Queen] in person was a dream come true. Royalty goes back centuries and to see someone who has that link with Great Britain in front of you, it’s empowering. It’s a buzz.”

There’s a certain logic to this meeting between Robert John Arthur Halford of Walsall and Elizabeth Alexandra Mary of Windsor. Both are pinnacles in their realms. He is known to friends as MG or Metal God. She has a title less succinct, but almost as potent – Her Majesty The Queen, by the Grace of God… the British Dominions beyond the Seas… Elizabeth II’s title also includes the phrase Defender of the Faith. By neat coincidence, Judas Priest’s 1984 album was called Defenders Of The Faith. The band, variously, come from West Midlands outposts – Walsall, West Bromwich, a big spread of council housing called the Yew Tree Estate. The Queen doesn’t have many obvious links with these areas, but she did look to the Midlands to produce the medal for her Diamond Jubilee. If you’re looking to make your mark in hot metal, where else would you go?

“Imagine me coming out in ’84 or ’85. I think there’s a chance metal’s house of cards might have collapsed.”

Rob Halford

HEAVY METAL IS SYNONYMOUS WITH BOTH JUDAS Priest and with the West Midlands. The grim reaches of Mordor in Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings were inspired by the industrialised grime of the Midlands area known as the Black Country. And, adjacent to the Black Country, in Birmingham, were Black Sabbath. With their black magic references and invincible down-tuned grind, Black Sabbath were the musical equivalent of Tolkien’s giant, whip-wielding Balrogs – charismatically brutal, clearing the way for others to follow. Judas Priest acquired their full rock heaviness a little after Sabbath had made their mark, but they pulled on heavy metal’s armour like no one else. After all, Judas Priest had grown up in close proximity to metal – as in the furnaces and forges that lingered on from the industrial revolution.

“As a teenager,” says Halford, “I would walk from our council house on the Beechdale estate in Walsall to the Richard C. Thomas School in Bloxwich. Spring, summer, winter – past pig-iron factories, bridges, canals. I would actually see molten metal coming out of the cauldrons and running down the gullies. It was like an apocalyptic environmental nightmare. I’d have this grit in my eyes, breathing in these fumes. That was heavy metal. I was breathing in the fumes of heavy metal before the music was even invented.”

Halford’s dad worked at Tubefabs, a Walsall metalworking company making components for nuclear reactors. Here was weighty metalwork beside plutonium and uranium – elements that chemists group among the heavy metals. How could there possibly be a more metallurgically Midlands background? Well, perhaps Glenn Tipton’s, one of Judas Priest’s two current guitarists. Tipton not only shares his surname with a Midlands town, but was also an apprentice at British Steel, the now-defunct nationalised industry that gave Judas Priest the title for the 1980 album that took them to Number 4 in the UK chart.

“We really did grow up in a labyrinth of heavy metal,” says Tipton, now 66 but still with the hair and shades of a rock lifer. “There were huge foundries, big steam hammers. It gave you a determination to get out…”

A band called Judas Priest began playing live in 1969 – but none of that line-up features in Judas Priest 2014. The original Priest were fronted by Al Atkins, a bluesy Paul Rodgers-style growler from West Bromwich. The Atkins-fronted Judas Priest gigged for four years without making it to vinyl. The venues didn’t indicate impending stardom: Hucknall Miners’ Welfare Club in Nottingham; Doncaster Top Rank; somewhere called Boobs in Merthyr Tydfil; the Brumling Budgie Club in London; a higher-education establishment with a particularly Midlands ring to it – Birmingham’s College Of Food And Domestic Art.

THE NAME JUDAS PRIEST – TAKEN from the Bob Dylan song The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest – was almost left to reside with the band’s original singer. In 1973 Atkins had left the band and considered launching a new Judas Priest with a new line-up, all of whom happened to be black. The name ended up in other hands – those of Midlanders Kenneth Downing and Ian Hill, who had found a new singer. Hill was going out with – and eventually married – Rob Halford’s sister. The essential Judas Priest line-up was taking shape: vocalist Halford, guitarist K.K. Downing, bassist Ian Hill. Glenn Tipton completed the band’s core quartet when he joined in 1974.

Judas Priest’s debut album, Rocka Rolla, was released in 1974. The cover featured a visual play on the Coca-Cola logo that graphic artist John Pasche had first offered to The Rolling Stones for their Goats Head Soup album. The songs on Rocka Rolla also had a second-hand element, with some of the composition coming from the Al Atkins era. The album – rooted in the earthy verities of blues rock – made little impact. Judas Priest had yet to find the sounds that would define both themselves and heavy metal.

“We knew Sabbath very well,” says Halford. “There was also that power in The Edgar Broughton Band, The Groundhogs and King Crimson… all before metal had been defined. That heaviness was already there, but we turned it up a notch and homed in on the riff. Vocally, I was interested in both Elkie Brooks and Robert Palmer in Vinegar Joe, in Roger Chapman from Family, in Little Richard, Janis Joplin, Planty – just listening to what the human voice was capable of and wondering what that would sound like in a heavy metal context.”

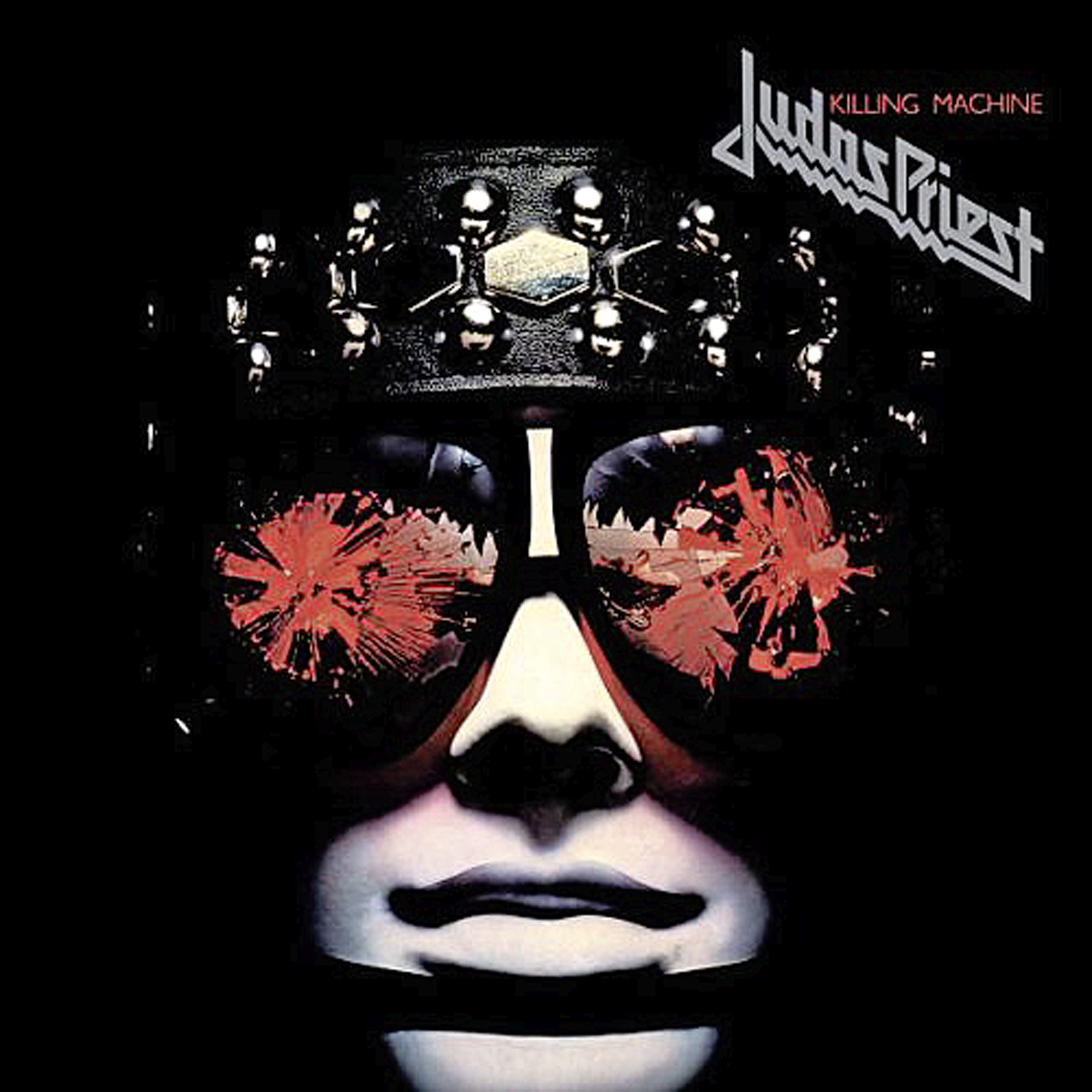

It was with the run of albums from 1978 to 1980 – Stained Class, Killing Machine, British Steel – that Judas Priest perfected their heavy metal archetypes. The band played a key part in defining metal’s musical character: amplified distortion; hysterical expressiveness on every instrument; vocals pitched at the edge of human capability; the primacy of the insistent, staccato guitar riff. Suddenly here was popular music that sounded like tuned, harmonised power tools. But Judas Priest also laid down definitive heavy metal dress-codes. By 1978, Halford was wrapped in leather and studs, and wielding a whip. Handcuffs dangled from his waist. It was all hugely camp, with the music press suggesting Halford looked like an S&M version of Tim Brooke-Taylor – at the time a major TV presence in The Goodies. In 1979 Halford started riding a motorbike on stage, heralding the track Hell Bent For Leather.

“There was a place in Soho in London called Mr S, an S&M shop,” he says. “I’d get gear from Mr S and it would be on Top Of The Pops two hours later. The song that really generated all that was Hell Bent For Leather, which, actually, Glenn wrote. I said to Glenn, Why don’t we bring a bike on stage? It was a Midlands show, maybe Derby. There were always some bikers at Priest shows, so I said to one of them, Lend us your bike and I’ll have it on stage. The place just erupted. That was a tipping point and we thought, Let’s expand on this. The bike is still there today. It’s like Angus and his shorts, you gotta do it. Leather is a primeval, primordial, animalistic look. I remember seeing Elvis in his ’68 Comeback special. I thought, Look at that hero, there in his leather. I was looking at some footage from the recent Pride parades and as soon as the leather guys go by it’s a completely different vibe. Everything and everyone is different in leather. In heavy metal it conveys confidence and power.”

Today, Halford talks casually, affably, about watching footage of gay pride marches. He recently referred to himself in The Guardian as “the stately homo of heavy metal” – a hard-rock adjunct to the “stately homos of England”, as coined by Quentin Crisp. Halford also jokingly – but supportively – addressed the Florida prog-rock band Cynic, two of whom recently came out.

“I ain’t having that,” said Halford in an interview in Terrorizer magazine, “I am the only gay in the village!” – echoing Matt Lucas’s line in the recurring Little Britain sketch. But though Halford’s sexuality was understood by his bandmates, for much of Judas Priest’s career it was under wraps. Halford had fears about coming out as a gay man while working in the neurotically macho metal world.

“If you imagine me coming out in ’84 or ’85 at the peak of the gigantic metal movement,” he says, “I think there’s a chance metal’s house of cards might have collapsed. Life was different then. I think we were protecting each other, for the right reasons. That it might have had some destructive kickback was important to consider.”

“There were always some bikers at Priest shows, so I said to one of them, Lend us your bike and I’ll have it on stage. The place just erupted.”

Rob Halford

IN RETROSPECT THERE WERE CLUES in Priest’s lyrics. In 1980, the British Steel album brought a commercial quantum leap for the band in the UK – as well as making the Top 40 in the US. In the track Grinder, Halford sings “Never straight and narrow… Been inclined to wander/Off the beaten path.” When this writer asked Halford about these lyrics in 2010, on the 30th anniversary of the release of British Steel, he said he’d never previously been asked about these possible subliminal indicators, but that, “Yes, subconsciously, maybe that’s what it was. It certainly felt right. Why would I say, ‘Never straight and narrow…’?” Halford eventually came out in 1998 – during a period in which he’d left Judas Priest. As things have panned out, his sexuality has only produced occasional adverse reaction.

“When we played in St Petersburg recently,” he says, “the mayor’s office told us not to make any reference to gay rights. But I wouldn’t have wanted to do that anyway. I’m not an activist, but just me standing on that stage in that very homophobic place was a victory. I didn’t have to go on waving a rainbow banner. I am the rainbow flag of metal. I consider it a triumph, just the fact of us playing there.”

As with his fondness for Queen Elizabeth, Halford is a great admirer of Queen, the band. He says that Freddie Mercury’s decision not to come out maybe had some bearing on his own course.

“Everybody in Queen knew Freddie was gay,” he says, “and everybody in Priest knew I was gay. But he didn’t bring it into the limelight. That was probably in the back of my mind – Freddie’s not talking about it so why should I? Freddie is a hero to me. The closest I ever got to Freddie was in a gay bar in Athens on the way to Mykonos. We kind of glared at each other across the bar, in a kind of smiling, winking way. When we got to Mykonos I was determined to track him down, but I couldn’t because he’d rented this huge yacht. It was festooned in pink balloons and it just kept sailing around the island. He’s someone I wish I’d really met. I always regret not just walking over and shaking his hand.”

Through Judas Priest’s early-’80s boom time, Halford was clearly having fun – his sexuality may have been an official secret, but the leather and lyrical provocation meant his lifestyle was hardly that covert. The video for 1981 single Hot Rockin’ is an extraordinary slice of pro-am metal homoeroticism: Tom Of Finland relocated to a Walsall leisure centre, with Judas Priest cavorting semi-naked in the gym, shower and sauna. But while, in his own particular way, Halford was managing his sexuality, in other areas he was losing control.

“Cocaine,” he says. “I was snorting that like there’s no tomorrow. It’s a horrible, horrible drug. I used to drink vodka and tonic when I was on stage and I’d be doing lines of coke behind the speaker stacks. Then I’d come off stage and have a bottle of Dom Pérignon and half-a-dozen cans of beer. So, times that by five shows a week. It was a classic case of being utterly out of control. They say you have to hit rock bottom and when I hit that proverbial wall it was very, very serious. I was taken to hospital in Phoenix in 1986 and I haven’t had a drop of alcohol since. I still yearn for it now, but I can’t just have one drink – that is the addictive disease of alcoholism. When I see Glenn drinking today I think, Fuck, I could really crack one of them. But I know I can’t.”

Halford’s drugs crash was a bleak point, but for the band there was worse to come. In 1990 Judas Priest entered a Nevada courtroom. In 1985 two young Americans, James Vance and Raymond Belknap, had spent an afternoon drinking, smoking dope and listening to Judas Priest records. Belknap then decided to kill himself with a shotgun. Vance maimed himself with the same gun, dying three years later from his injuries. The pair had allegedly been prompted by a subliminal message on 1978’s Stained Class – supposedly contained in a cover of the Spooky Tooth song Better By You, Better Than Me. The parents of the deceased, and their legal team, argued that the Priest recording acted as a trigger. The case was eventually dismissed in court, but such a bleak interlude is unlikely to be forgotten.

“It still crosses my mind,” says Halford. “Firstly, the loss of those lads and then the terrible injustice that was done to their memory, because they loved their metal music, they loved Judas Priest and their passing was used in a very nasty way, from people who couldn’t accept the reality of the situation. To put the blame on a band who were 8,000 miles away, on a song that was years and years ago, it was just ridiculous. It was a very, very difficult time for us, personally, emotionally.”

JUDAS PRIEST RELEASED THE Painkiller album soon after the court case. It followed an excursion into MTV-friendly synth-guitars with 1986’s Turbo album and the self-parodic Ram It Down in 1988 (which failed to live up to the base-metal bravado of titles such as Heavy Metal and Monsters Of Rock). Painkiller renewed the band’s signature sense of power but also refreshed the group by taking in the speed metal of Metallica and Megadeth, bands Judas Priest had strongly influenced. But just as Priest seemed to be rejuvenated there was further trauma. In 1992 Halford announced he was quitting. Today he says this decision had nothing to do with the court case – he felt he needed a break from the working environment he’d been enmeshed in since 1973.

Halford now admits his exit could have been better handled – and that the ensuing acrimony might have been avoided. In a 1993 press statement Halford talked about needing “to protect himself against Mr Tipton, Downing and Hill’s tyrannical behaviour”. In return the Priest rump objected to the “demented mumblings of our ex-vocalist Robert Halford”. The singer released albums under a series of new band names – Fight, Two, Halford. The remaining members of Judas Priest found a new singer – Tim ‘Ripper’ Owens, whose previous activity included fronting a Judas Priest tribute band called British Steel. Owens’s odd interregnum became the basis for the 2001 film Rock Star, with Mark Wahlberg taking the Ripper role.

In a 2001 interview, K.K. Downing announced that, “Rob Halford will never sing with this band again, because he doesn’t fucking deserve it.” By 2004 Halford was once more singing with Judas Priest – and continues to do so to this day, albeit now as part of a band which no longer contains K.K. Downing, who left in 2011 citing an “ongoing breakdown in working relationships”.

Over the decades at least 14 men have served under the Judas Priest banner. This metal multitude might be seen as an illustration of heavy metal’s traditional all-in-it football-terrace communality. Or it could make Judas Priest seem like some hard-rocking gang show, an entertainment spectacle of such essential potency that it exists above and beyond the individual. If heavy metal’s crowd-pleasing conventions can occasionally make it seem like very loud pantomime, or high-decibel music hall, such comparisons don’t worry Halford.

“I wouldn’t take offence in the least,” he says, “because I love both those things. It takes a lot of work to make a really good panto. The biggest film in America right now is the new Transformers film and that’s kids’ toys made into this billion-dollar movie. I like that – the childlike quality in humanity that we’re drawn to. In fact, the Transformers aren’t far from something you’d see on a Judas Priest album sleeve. ‘Loud pantomime’ is one way of looking at what we do – 50 million albums later…”

A new movie-style fiend glares out from the cover of the Redeemer Of Souls – a winged ghoul wreathed in fire. As Halford says, “In what other form of music could I have written about something like our Painkiller creature and got away with it. You can’t do that in jazz…”

If Judas Priest’s thrill-packed showbiz heritage needs any further underlining it comes with new guitarist Richie Faulkner, a 34-year-old Star Wars fan from north London. Before he joined the band in 2011, his most notable musical role had been as arranger on a heavy metal concept album, Charlemagne: The Omens Of Death. The vocalist on that album has a history of sinister success that eclipses even that of Judas Priest – Sir Christopher Lee. “A great guy,” says Faulkner. “He’s 92 and he’s making heavy metal records…” It seems heavy metal is an all-ages arena. “My mum is still a headbanger,” says Halford. “She can’t wait to hear Redeemer Of Souls. She’s just turned 86, bless her.”

As we close the interview and Judas Priest prepare to descend into the Manhattan heat, Halford looks around Sony’s plush New York eyrie and meditates further on his Midlands origins. “The first thing I do when I go home is go for a curry,” he says, “to a balti house in Caldmore, in Walsall. Walsall is a tough place, a working-class place, but it’s important to me… We always go back to the Midlands to rehearse for tours. The Midlands is what made us – and what made heavy metal.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 252 of MOJO