Mojo

FEATURE

The Thunder Machine

Ginger Baker was one of the iconic architects of rock’s expansive era, a drummer who played as if literally possessed. He was also intimidating, contrary, complicated, imperious and unpredictable in ways his peers and progeny are still coming to terms with. “He seemed like a person who’d experienced pain and was carrying it with him,” they told Mark Paytress in 2019.

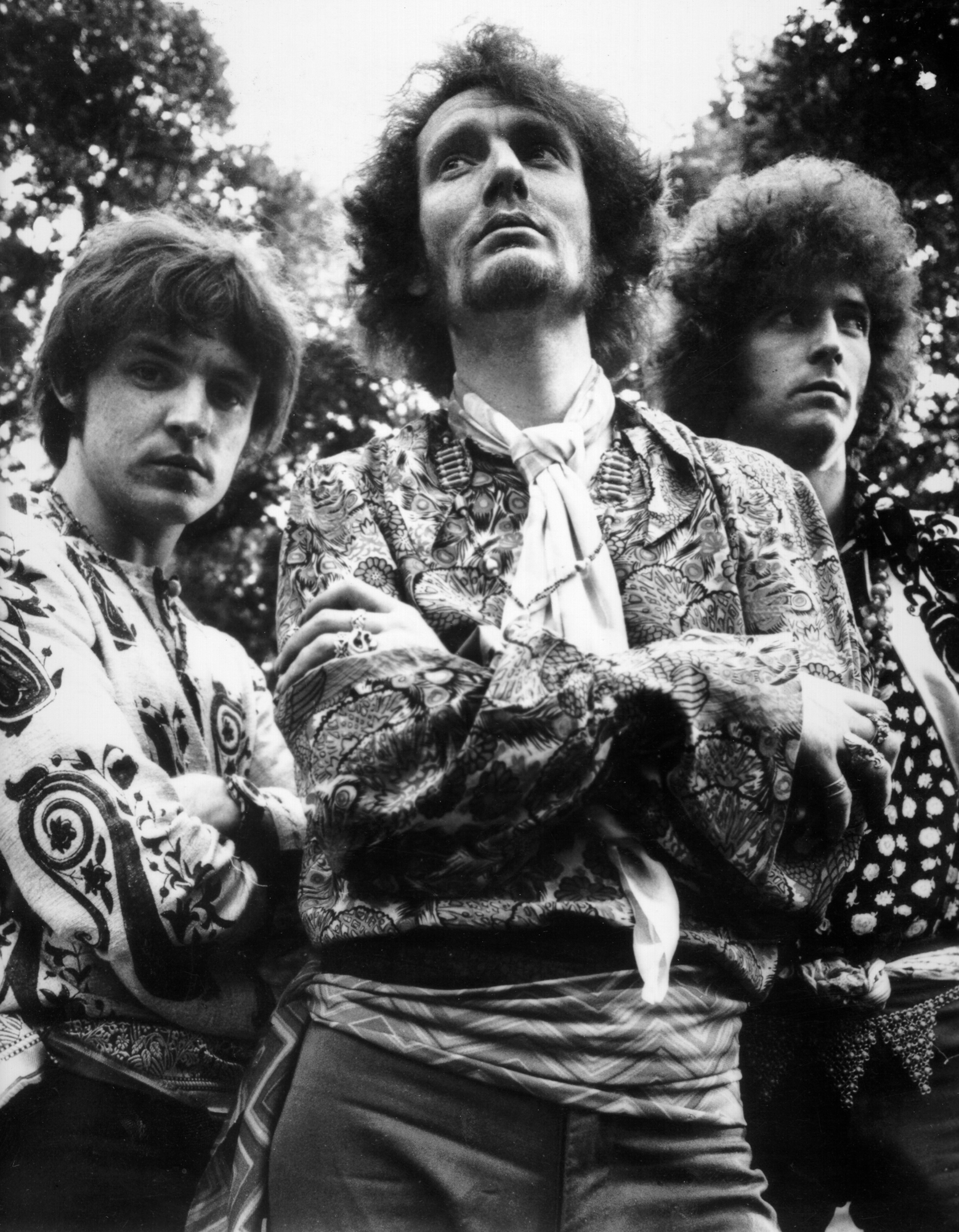

Cream (l-r) bassist Jack Bruce, drummer Ginger Baker and guitarist Eric Clapton.

NOVEMBER 26, 1968: Jack Bruce, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker walk out onto the Royal Albert Hall stage to a hero’s welcome. The crowd’s joy at their nine-song set, dominated by exhilarating feats of improvisation, is tempered by the knowledge that the evening’s two concerts will be Cream’s last. For the past two years, thanks to an unprecedented cocktail of volume, virtuosity and one or two classified ingredients, the trio had transformed contemporary music. By taking a jazz approach to a repertoire of blues- and pop-oriented songs, Cream had created a new form.

The new, grown-up rock world grieved the early demise of this trailblazing young trio. Not Ginger, though.

“No!” barked the man from his recliner when I visited him at his home outside Canterbury in 2014. “A ruddy relief.”

Director Tony Palmer, who filmed the farewell concerts for the BBC, takes a more considered view. “I felt Ginger was a lost soul after Cream exploded. And, I’m sorry to say, the same is true to some extent of Jack and Eric. Eric eventually found some peace but I’m not sure Jack ever did. Ginger certainly didn’t. It was very much like, You can’t top that, but you have to go on living.”

To the surprise of many, that’s exactly what Ginger Baker did, and with all the mad abandon of a man trapped in one of his extended drum solos. When he died, on October 6 2019, it wasn’t the decades-long heroin habit or his ability to make a Range Rover dance that saw him off. Via a blog message in 2016, he announced: “Just seen doctor… big shock… No more gigs for this old drummer… everything is off… of all things I never thought it would be my heart…”

Though the cause of death has yet to be made public, it’s likely that the heart was involved one way or another. “Without his drums, his life ceased to have any proper function,” says Palmer. “I’m sure Ginger loved his many wives, but his prime responsibility was to give a good account of himself with his drums.”

“If we’d played the music of Humpty Dumpty and Mickie Mouse, Cream would have still been great.”

Ginger Baker

PETER EDWARD BAKER was born in Lewisham, south-east London, on August 19, 1939, and born for a second time one late summer day in 1955. That was when, fresh out of school and at a party, Baker was persuaded by some old classmates to have a bash at a vacant drum-kit. His compulsive desk beating in class had not been in vain: “Christ, we’ve got a drummer!” said one of the horn players. Baker overheard them, but it had felt good anyway. Within days, he’d bought a £3 toy kit which he customised to boost its capabilities. The music he listened to for inspiration was The Quintet Of The Year, whose LP he’d stolen from a shop two years earlier. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charlie Mingus and drummer Max Roach – Baker started at the top.

Naturally gifted, he worked his way through London’s ’50s jazz scene, confounding ‘traddies’ with his offbeats, impressing Sister Rosetta Tharpe – who wanted to take his trousers down – and earning a reputation. He taught himself to read and arrange music, and the earnings graph on his bedroom wall continued its upwards trend. It had to be so because he’d married Liz in 1959, and become a father to Ginette (alias ‘Nettie’) the following year.

During the early days with Liz, Baker made it clear his playing would always come first. The kit was both mistress and protector to a man whose sanity was often questioned. “I think it was the fame and the drugs,” says Baker’s son Kofi, born in 1969 and a drummer like his dad, currently playing with Jack Bruce’s son Malcolm and Eric Clapton’s nephew Will Johns (son of engineer Andy) in The Music Of Cream. “Mum said people would come up to him and say, ‘Ginger, you’re God, you’re the greatest.’ And he was high and he’d be like, ‘Yeah, I am the fucking greatest.’ She said he only got like that when he got into heroin and got famous. She said he really changed. I mean, he was always a nutcase. Both my parents were nutcases.”

Heroin. Like smoking dope but better, drummer Dickie Devere told Baker in May 1960. Later that week, before going on-stage with The Johnny Scott Band in Brighton, Ginger had another snort. He’d found the answer, Baker wrote in Hellraiser, the autobiography he wrote with Nettie: “All the barriers were down and I was just playing.” He happily acquired a habit.

Later that year, another epiphany. The jazz great Phil Seamen walked in on Baker playing a session at the Flamingo in Soho, “You can play,” he told Baker, who’d copied Seamen’s habits of playing with a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, as well as his ‘matched grip’ (both drumsticks held with the hand over the top). The man Ginger called his ‘Drum God’ invited him back to his Maida Vale flat. It was an eventful night. Smack addict Seamen had Baker help him jack up, then told him never to go near the stuff. Hours later, as he walked home, Baker still had the rhythms of the Watusi Drummers in his footsteps. “For the first time, I felt the pulse of Africa,” he recalled.

GINGER WAS FLYING. One night in autumn 1962, he’d sat in with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated and, according to sax player Dick Heckstall-Smith, had driven the band through the Marquee roof. Regular drummer Charlie Watts resigned so Baker could take his place. Within months, Baker, bassist Jack Bruce and organist Graham Bond all quit. (Heckstall-Smith followed soon after.) Going out as The Graham Bond Organisation, the quartet earned a fearsome reputation in the clubs, their tough R&B material styled up with jazz-honed virtuosity. Baker cooked up the artwork for the The Sound Of ’65 album, his distinctive solos started to acquire titles (Camels And Elephants) and, early in ’66, he even sold an Organisation outtake (retitled Waltz For A Pig), to The Who. He bought a new Rover 2000 with the proceeds.

After three years, Baker – dubbed ‘The Thunder Machine’ by the press – needed a new challenge. Ditto disgruntled Blues Breakers guitarist Eric Clapton, or ‘God’ as his fans knew him. Clapton had seen Chicago bluesman Buddy Guy’s trio months earlier and convinced Baker they just needed a bassist. Only one man fit the bill – Baker’s Bond Organisation nemesis Jack Bruce.

The temperamental two had previously fallen out while Baker was detoxing, leading to on-stage punch-ups and ultimately, in August 1965, Bruce’s departure. Baker accused the bassist of playing too loud and over his solo. “I was trying to find a new way of playing,” Bruce explained years later to Phil Sutcliffe. “It was kind of busy and Ginger didn’t like it.”

Launched at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival on July 31, 1966, Cream – initially The Cream, in case anyone doubted their pedigree – was the product of everything Baker had been working towards. “If we’d played the music of Humpty Dumpty and Mickey Mouse, it would have still been great,” he told me in 2014. “It didn’t matter what the song was. It was the people that played it that made it.”

Cream wrote and played songs for fun and fame but their primary purpose was to explore. On a good night, the effect of their instrumental surges could be transcendent – and not only for those fashionable acid trippers in the audience.

“This happens to us quite often,” Baker told Hit Parader’s Jim Delehant. “It feels as though I’m not playing my instrument; something else is playing it and that same thing is playing all three of our instruments… It’s frightening sometimes.”The trio’s connection was, he claimed, comparable to ESP.

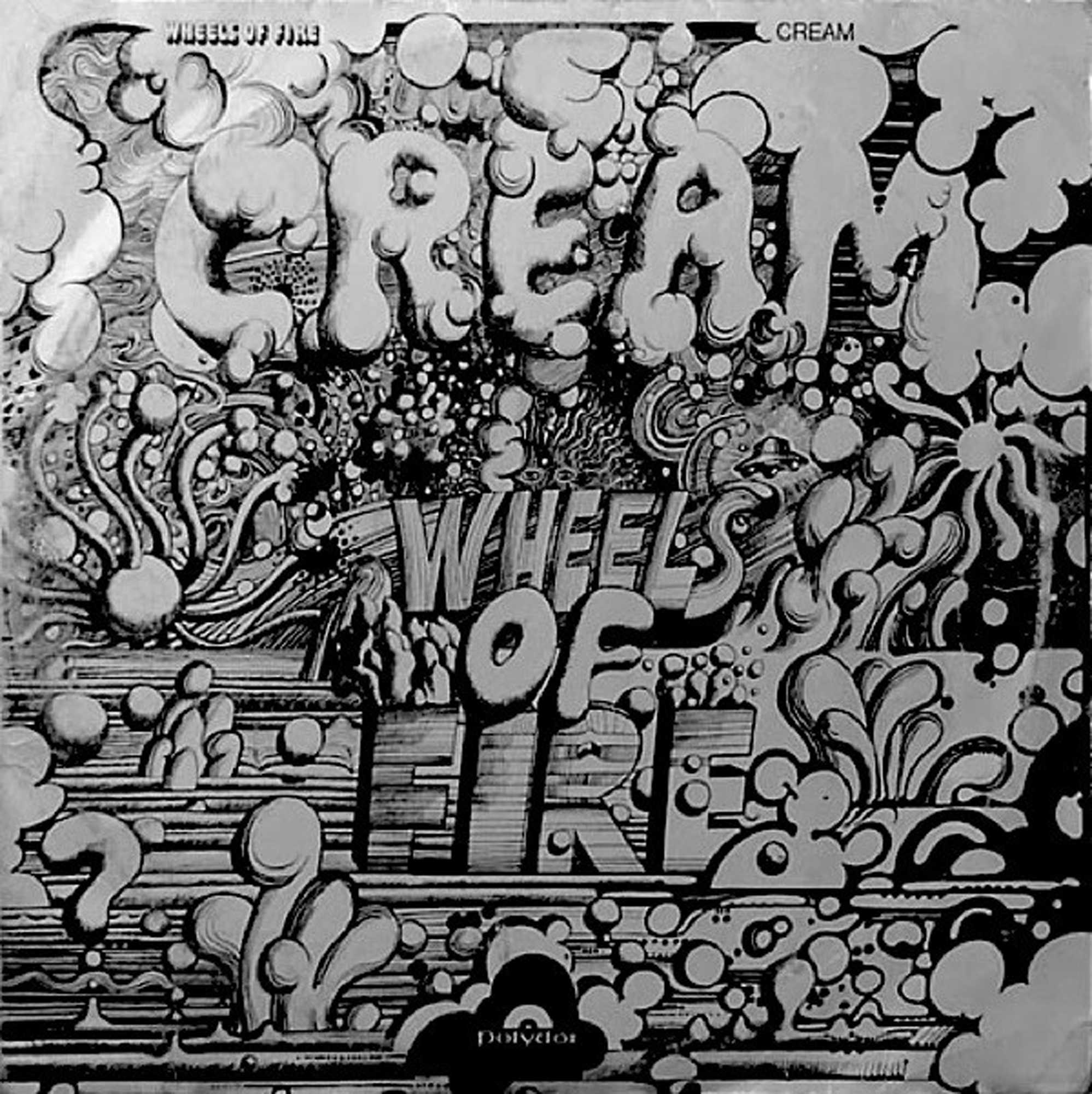

Tony Palmer, who heard Cream in concert many times before filming the Albert Hall shows, insists tension – as much as teamwork – was key to the group’s achievements. “There was this intense musical rivalry between the three of them which made Cream so extraordinary,” he says. “The LPs are poor because in the studio you’re more disciplined. On stage, they were immensely disciplined, but in a totally freeform way. And they got that from Ginger.”

Writing for the Harvard Crimson late in 1968, the distinguished future composer John Adams provided a fascinating portrait of Ginger Baker at the height of the group’s fame. Baker, he wrote, is “like a beast from another world”. His “ghastly croaks begin somewhere down within his sinewy frame and emerge through a crooked row of half rotten teeth.” After a performance, “his whole nervous system is so wracked by amphetamines that he literally has to be carried off the stage.

“If Baker lives for another year it will be a miracle,” he predicted. As for Cream that October night in New Haven: “On the stage, in that blue light, they were superhuman.”

“People would come up to him and say, Ginger, you’re God. And he was high and he’d be like, Yeah, I am.”

Kofi Baker

CREAM MIGHT HAVE been a spiritual experience for Baker, but once Clapton heard The Band’s Music From Big Pink earlier that year, he felt the game was up, that Cream were a con. They had jammed themselves into oblivion. Returning to the family home in Harrow, now swelled by the arrival of a second daughter, Leda, Baker continued to work on the fibreglass and steel sculpture he’d been creating since the group’s first days. The pleasure, it seemed, was more in the journey than the destination.

The “ruddy relief” of Cream’s dissolution had a personal downside for Baker. Now 30 and a millionaire, he returned to his old heroin habit without restraint. Hearing Clapton was rehearsing with Steve Winwood, then extricating himself from Traffic, Baker turned up at the door of Winwood’s remote Berkshire cottage to announce that the pair now had a drummer. Clapton, who now regarded Baker as “seriously antisocial”, was crestfallen. Hyped into instant ‘supergroup’ status, Blind Faith toured the States for six lucrative weeks in the summer, and had fizzled out by October.

While on the West Coast, Baker heard he’d been found dead from a heroin overdose in his hotel. He was belting down Route 101 in an AC Cobra at the time with three female passengers and a car radio. As he wrote in Hellraiser: “I looked round at the chicks and thought, Fucking hell, I must be in heaven!”

His own 10-piece big band, Ginger Baker’s Air Force, lasted no longer than Blind Faith. Heavy friends included Winwood and ex-Moody Blues man Denny Laine. Graham Bond and Phil Seamen were reeled in from Baker’s past. But it was the presence of percussionist Remi Kabaka and the band’s Afro-jazz leanings that suggested Baker’s next move.

According to Bill Laswell, who saw Cream when he was 14 and worked with Baker in the ’80s, “Ginger could have moved to LA and become like Fleetwood Mac. He could have pulled that off. But he decided to go to Africa.”

“A lot of stars at that time – and John Lennon’s a perfect example – felt they missed out on their education,” says Tony Palmer, who in 1971 accompanied Baker on his second trip to Lagos, Nigeria, to film a documentary. “For Ginger, it was in every sense a journey of exploration. The drive across the Sahara took at least three times as long as we thought it would simply because he kept stopping, looking and talking to people.”

Palmer found his travelling companion differed markedly from his reputation: “He was absolutely delightful. Witty, concerned about our welfare and anxious to be a good guide and a good guy.”

On reaching Lagos, Baker headed straight for Fela Kuti’s Afro-Spot nightclub. All the downers back home, including the recent death of his friend and fellow free spirit Jimi Hendrix, ebbed away. “You couldn’t stand still and listen to that band,” he told me in 2014, still visibly moved by the memory.

“Ginger felt there was a whole world of music, relatively unexplored, that was not rock’n’roll,” says Palmer. “We filmed an amazing session at a gathering of talking drummers. And he gave as good as he got. It’s your beats and patterns of beats that do the speaking, giving voice to his thoughts at that moment. It was astonishing. Ginger was new to it, but he clearly found his voice.”

Ja’Baka, as Baker was known locally, made himself at home in Lagos, and made albums with Fela Kuti in London. In Ikeja, he built a 16-track studio, dubbed ARC, and persuaded Paul McCartney’s Wings to come and record Band On The Run there. But he hadn’t reckoned on the intimidatory tactics of associates of EMI’s existing Lagos facility – Baker’s rivals for the ex-Beatle’s business. Ultimately just one song, Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me), was taped at ARC Studios. “Ginger played a fire bucket full of gravel on that one,” remembers Denny Laine, by now McCartney’s foil in Wings.

Arriving at ARC one day, Baker discovered that the locks had been changed. As he sped away, the sound of gunshots filled the air. His Nigerian dream had collapsed. It was time to go home.

GINGER SOON FOUND HIS FEET. He formed Baker Gurvitz Army with guitarist Adrian Gurvitz and bassist brother Paul who, as The Gun, had scored a lone hit in 1968 with Race With The Devil. They bagged a big-money deal, enjoyed a major promotional push and their 1974 debut album hit Top 30. The band also included White Room and Sunshine Of Your Love, both key Baker arrangements, in their live set. This tended to happen whenever Baker joined a rock band over the next couple of decades, culminating in the BBM project in 1994 where, lured in by serious money and the promise of first class travel between Britain and the States, Baker was teamed with Jack Bruce and Gary Moore. He dismissed the venture as “a pretend Cream thing”.

“Cream was a jazz thing,” Baker insisted, dismissing two generations of pretenders. “It was 80 per cent totally improvised and never the same two nights running.”

“That’s why he despised people like John Bonham,” says Tony Palmer. “Ginger was a jazz drummer and that mattered to him.” It was, said Baker repeatedly, all about the swing. “Keeping metronomic time is not the same as swinging!”

By the end of the ’70s, Baker was divorced, broke and a bit of a joke. “People thought he was this drug addict and nutcase just blasting the drums,” says Kofi Baker. “As far as I know, Animal from The Muppets was modelled on my dad. They talked to my mum and asked if he’d be fine about it.”

But Ginger was past caring. He was back in the grip of heroin addiction, dating a friend of his daughter’s and was rumoured to be couriering coke to Olympic Studios while Eric Clapton and his band were recording 1978’s Backless. “Ginger didn’t behave himself terribly well, but that’s life on the road,” says Tony Palmer. “But the moment he split up with Liz, he knew he’d lost something, screwed something up.”

By 1980, Baker was drumming for Hawkwind. “He’d tell us all these stories about how he’d lost his money,” says Hawkwind mainstay Dave Brock. “It was a lesson for us. Let’s not end up like Ginger. This guy used to come round to deal him his bad drugs. We didn’t realise. He used to get a bit wobbly but we thought it was because he was drinking a bottle of Bacardi a day. The strangest thing was it never affected his ability. He just seemed to carry on regardless.”

Fed up with rock bands and facing an £84,000 tax bill, Baker fled to Tuscany in 1982 with future wife Sarah. He was off heroin and pruning olive trees. By the end of 1983, Sarah had walked out. “He was living on a hilltop,” says Bill Laswell, who flew in with a proposal for a new project. “No electricity, no telephone, lots of dogs. He seemed aged, like a person who’d experienced pain and was carrying it with him. His kit was set up in a room at the top of his house. You’d open these huge windows, look down into the valleys and there was nothing there, just some rundown castle. He’d play almost every day in that room.”

Laswell was putting together a studio band for the new Public Image Limited album, Album. “When I said the lead vocalist was Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols he really liked the idea. Though they were very different people, they’d come from similar backgrounds. And they both told people to fuck off a lot.”

After the PiL experience, Baker relocated to the US, ending up in LA by 1988. He recorded West African-flavoured albums with Laswell, and perhaps his best post-Cream rock album – Masters Of Reality’s 1992 LP Sunshine Of The Sufferbus. But it was his first love, jazz, that prompted a joyful creative flourish through the ’90s, first with The Ginger Baker Trio then The Denver Jazz Quintet To Octet.

He even embraced the unthinkable – joining Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton for a Cream reunion in 2005. Ginger was tempted by the money, which he used – and later lost – to build up his polo ranch in South Africa, where he met his fourth wife Kudzai. At the Madison Square Garden shows, Baker spotted a photo of Bruce Springsteen and removed it, a symbol of his unwavering displeasure at rock celebrities and post-Cream rock generally.

“As far as I know, Animal from The Muppets was modelled on my dad.”

Kofi Baker

When I interviewed Baker in 2014, he was slow, his skin was yellow, he chain-smoked and was still heartbroken at having to sell his 38 horses in South Africa due to more financial bad luck. “I’m naïve,” he explained. There were no traces of his musical past in the house. Large photos of Kudzai lined the hall. He fussed over his Dalmatian dog Jakey. A cushion bearing the words ‘Love Is All You Need’ lay on the sofa.

On September 25 2019, the Baker family announced that Ginger was critically ill in hospital in Canterbury. Kofi Baker flew in from the States. In 2018, he’d told Rolling Stone he’d been disowned so many times by his dad that he doubted he’d be upset by his death. “It was completely the opposite,” he says a week after losing him. “It fucking trashed me. I really thought he didn’t like me, or that I was just a disappointment to him. But it seemed like it was all just a front. I told him how I felt. He listened, his eyes lit up and he laughed. I told him I was learning [Cream’s] Blue Condition for the next tour and he was all happy about it.”

During those final days, Kofi had a conversation with percussionist Abass Dodoo from Baker’s last band. “He told me my dad was living through me, that he loved the fact that I was doing the Cream stuff again. I didn’t hear all this shit until a week ago! I’m like, What an asshole. I find out all this and the fucker’s died on me. I finally get to connect to you and you’re gone.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 314 of MOJO

MAIN IMAGE: GETTY