Mojo

FEATURE

Battle Royale

She punched him in the face. He sought to have her committed. Together, they explored life’s extremes and made some of the most audacious rock’n’roll of their era. In 2019, after years apart, Royal Trux were back – toting an extraordinary new album with a provocative title – but would their détente even outlast this interview? “Our thing is psycho complicated,” they assure Andrew Perry.

Keep on Trux-ing: Neil Hagerty and Jennifer Herrema

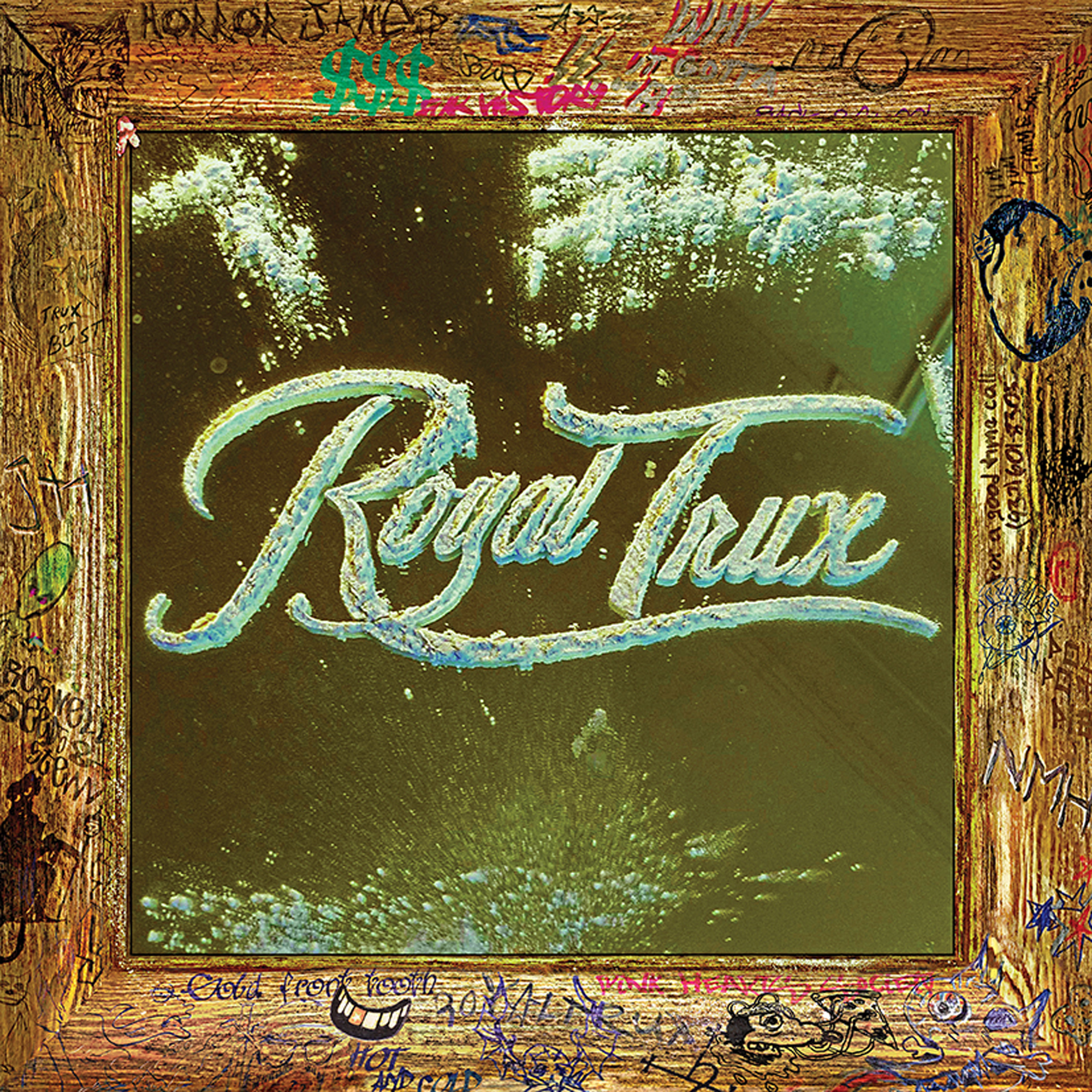

EIGHTEEN YEARS SINCE their combustible alliance blew apart in seemingly irrevocable acrimony, Jennifer Herrema and Neil Hagerty – former junkies; ex-spouses; the once (and, who knows, future?) queen and king of in extremis rock’n’roll – are sitting together in the bar of the Grafton Hotel on Los Angeles’s Sunset Strip. Against all odds, overcoming years of mutual alienation and mistrust, they’ve made a new Royal Trux album. If Herrema has her way and the pair can stop fighting over it for two minutes, it will be called White Stuff.

“Come on, man, don’t screw around,” snipes Hagerty angrily at Herrema, scratching at his shaggy salt-and-pepper beard, “it’s called Championship Pizza!”

“But I’ve worked so hard on the artwork,” counters Herrema from beneath her golden-blonde mane.

“It can’t be called that,” Hagerty quickly fires back, “or I’m not having anything to do with it. It’s like Exile On Main St. being called Abscess.”

As the argument lurches tetchily onwards, we learn that Hagerty and Herrema haven’t communicated at all in the five months between him walking out of album sessions three days early, and him walking into the Grafton a few minutes ago. It’s excruciating to witness the disconnect between them – Hagerty, the OCD guitar genius who rarely makes eye contact, and Herrema, the rock lifer with stellar magnetism and, to Hagerty’s mind, control-freak tendencies. Eventually, Hagerty storms out, and it really does look as if Royal Trux have split up, again, before our very eyes. Soon, MOJO is padding up and down the Strip, communicating separately with both parties, attempting to patch them back together – long enough, at least, to conduct our photo shoot.

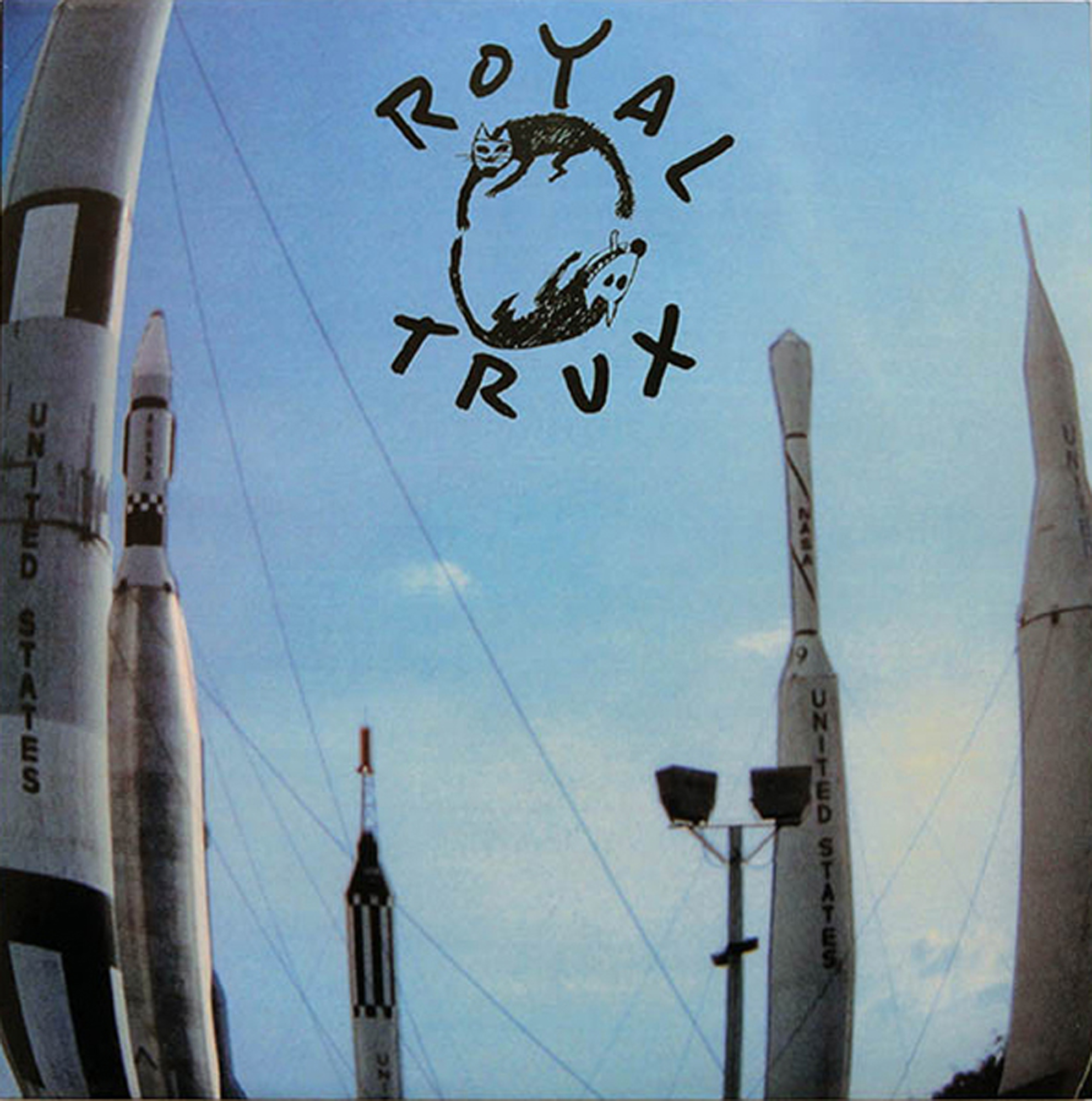

It’s all quite alarming, but surprising? Not really. In the ’90s, when they bent classic rock’n’roll into queasy yet seductive new shapes, Royal Trux specialised in self-sabotage, landing a major label deal only to taunt their paymasters with out-there albums in unmarketable sleeves. The group’s volatile central couple, who cohabited for 15 years, eventually fell apart when Herrema breached a shared commitment to rehab, the end point of the antagonism immortalised in the title of their 1993 magnum opus Cats And Dogs. And now?

“Everything in the Truxian universe remains the same,” beams Herrema in the Grafton bar, defiantly chugging a beer.

“We know a lotta people that died. That was our thing, junkies as entertainment.”

Neil Hagerty

JENNIFER HERREMA FIRST set eyes on Neil Hagerty one night in early 1985, as he played on-stage with his band Jet Boys Of North West, in the Adams Morgan district of Washington DC. She was just 15, he two or three years older, and already a college drop-out.

“I’d been going to see hardcore bands like Bad Brains,” she fondly recalls, “but when I saw Neil play, I was like, ‘This is the single best musician I’ve ever seen in my life.’ I’d heard girls that hung around him got their hair burnt off, and such.”

But, of course, she dated him anyway, and they soon bonded over unreconstructed heavy rock like Van Halen and the Scorpions, as much as DC’s prevailing Minor Threat-style punk. Two wayward kids on a collision course, they shared something darker, as there was a history of alcoholism in both their families, and they were both hardened drinkers by their teens.

Hagerty had tasted stronger stuff, too, while his military father was posted in Europe. “I did heroin when I was like, 12,” he says. “We’d go into Brussels to see concerts, and my friend’s older brothers would have a little hashish mixed with opium, like Black Sabbath used to smoke. We’d be throwing up all over the place.”

When Herrema was 14, her first boyfriend died from an overdose. “We know a lotta people that died,” summarises Hagerty, drily adding, “that was our thing, junkies as entertainment.”

They’d already started making music together when Hagerty was offered a gig in DC’s garage-noise unit, Pussy Galore, who were fronted by a pre-Blues Explosion Jon Spencer. That band’s big plan was to move to New York to be a part of the scene burgeoning around Sonic Youth. So, when Herrema was offered a college scholarship in the Big Apple starting in autumn ’86, they moved there, living together, after a fashion, with Hagerty sneaking into her female dorm at the YMCA every night.

“Neil was very creative, as a guitarist,” says Spencer today. “Wild. Fearless. A real force. He was in and out of Pussy Galore at least three times. I can’t remember when heroin addiction started, but there was always dabbling, and with a lot of different substances. We were all pretty mixed up, lacking in communication skills, and quite volatile. Some time while making [1987’s] Right Now, Neil announced that he wanted to be called Royal Trux from then on. Neil and Jennifer were writing and making home recordings, and at some point Royal Trux morphed into the band.”

The increasingly drug-dependent duo relocated to the more affordable environs of San Francisco, and there they plunged into a pit of junkiedom luridly documented on their second long-player, 1990’s Twin Infinitives – an unfathomable space-rock double-album, rife with Funkadelic-style improv, Moog weirdness and all-eclipsing claustrophobia.

“It wasn’t particularly an anti-social record,” says Herrema. “We were just fucking wasted. I was dancing, stripping, everything, because I had to take care of Neil’s habit as well. It’s always easier for the female to scrape up money, and part of me still resents the fact he allowed that to happen. (Deep breath) Our thing is psycho complicated.”

“She knows I was totally against it,” Hagerty maintains. “I was like, ‘It’ll change everything’, but she was adamant.”

Neither Herrema nor Hagerty is timid in divulging the gory details of their addiction. For Herrema, these included cohabiting with a dealer, hospitalisation with blood poisoning, and spells in sheltered accommodation, because her father’s alcoholism disqualified her from returning home. For her partner, there was living on the streets, an escalating crack problem, and an intervention prompted by Drag City, the label who’d released Twin Infinitives.

Hagerty got clean first, and though he apparently cut a solo acoustic version of what became the self-titled third Royal Trux album, he couldn’t pursue it without Herrema. “I owed her everything up to then,” he reasons. “She helped me so much.”

Herrema would complete rehab on the fourth attempt, and, with no fixed abode, Royal Trux hit the road, acquiring supplementary members variously in Florida and Kansas. Everything snapped into a uniquely strange focus on Cats And Dogs, where Herrema’s throaty yowl and Hagerty’s reedy sneer united in a kind of out-of-whack double-tracking, and where Stones-y raunch was leavened by cosmic otherness. “The fucked-upness in the music,” states Herrema, “was never about the drugs.”

ROYAL TRUX STOOD apart from most American alt rock, post-Nevermind. Yet, their fortunes rose.

“Sonic Youth had us open for them, and we got on Lollapalooza,” Hagerty recalls. “So we were out there, like, ‘Hey, we’re one of those bands, too!’ We wanted success, but it had to be right, and real.”

A bidding war flared, and Herrema brokered a deal with Virgin worth $1.4 million. “The beauty of it was,” she says, “we got to administer our own budget. They just had to send us the money when we asked.”

The label showed only mild concern when, for their “starter record”, they hired producer David Briggs, the Topanga Canyon crazy who’d helmed umpteen Neil Young albums. The resultant Thank You was their most accessible outing so far, its greasy groove finessed by a hot new band. Before recording in Memphis, they’d been drilled at a rental house in remotest Virginia, where Jennifer and Neil were planning to move, far from drug connections.

“We all lived together,” says bassist Dan Brown, “and we ate the same food. I read every book Neil had, and he read all mine. We played constantly. We were like [master science fiction writer] Robert A. Heinlein’s Grok Mind. Briggs loved the band, which was a great validation.”

Though the album established Royal Trux transatlantically, shifting 50,000 copies, they put the brakes on any fast-tracking themselves. “We chose to tour Britain with Teenage Fanclub, instead of Bush,” Hagerty says, “because we thought that would be the lesser thing, but it still wasn’t a good fit. We purposely wanted to be awkward and inappropriate.”

Back in Virginia, says Herrema, “we were like, ‘Briggs is doing the next record,’ and there was nothing Virgin could do. Briggs was saying, ‘Don’t go into another studio, we’ll build one at your place.’ He was such a bad-ass. I found us a house out in the woods, but a month before we were gonna start, Briggs’s wife Bettina called. He’d always had a bad back, but they found it was lung cancer. Then it was, ‘We’re gonna continue on, the exact way he said.’”

Once they started, however, Virgin hated advance tracks, not to mention the working title, Pol Pot Pie. The A&R who had signed them had taken a job as managing director elsewhere, the Spice Girls had taken off, and label priorities were changing. Virgin ultimately went through the motions of releasing the album, renamed Sweet Sixteen, but tellingly didn’t bother to veto its unpalatable cover image, of a toilet bowl full of vomit.

Weeks later, Virgin effectively paid them not to make another album, handing over a severance settlement of $300,000, says Herrema, à la Malcolm McLaren in The Great Rock ’N’ Roll Swindle, “to just go away”.

Royal Trux duly returned to the indie sector with Drag City (US) and Domino (UK), and, says Hagerty, “In my mind, we were set for life. We’d live in our house in the woods, and send out tapes every six months, like Can, in a state of constant creation.”

“The fucked-upness in the music was never about the drugs.”

Jennifer Herrema

THE WHEELS CAME OFF after only four years, just as your correspondent visited them at home in March 2000. ‘The Ranch’ was set on a wooded hillside near the Blue Ridge Mountains, a few miles from smalltown Washington, Virginia. Outside, a skull and crossbones drooped from a flagpole, and within, the couple’s three cats scurried between the huge animal hides draped over walls and furnishings alike.

In keeping with their image as alt rock’s wacko recluses par excellence, Hagerty and Herrema kept entirely opposite hours: he would sit up all night devouring novels, only to retire just as she was rising for the day. “I always loved the sunshine,” she shrugged, “and he always loved the night.”

On our second morning there, the atmosphere had discernibly changed: Herrema was slurring and incoherent, and a huge argument kicked off when Hagerty discovered she’d raided an emergency stash of barbiturates.

“We’d been living there six years and I didn’t want to any more,” says Herrema today. “I didn’t ever want to jeopardise Neil’s sobriety, so I’d play normal, but right when you visited, I got the call saying my dad had fallen out of a tree and broken his clavicle, and when he went into hospital, they found out he had cancer, and had three months to live.”

She’d had wobbles before, but now she dramatically fell off the wagon, getting hooked on painkillers prescribed to her father. A month later, she went to Los Angeles to house-sit for Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley, and was arrested “while driving his girlfriend around with a trunk full of GHB.”

There was a fraught European tour for that year’s Pound For Pound, but they’d only completed two dates on the American leg, when, says Hagerty, his other half “called the emergency room in Minneapolis, saying she was dying, so she could get an ambulance to the hospital, and get on a morphine drip.”

Says Dan Brown, “We had an intervention in the hotel room, and we were fucking crying, man – we were concerned about her. She was just like, ‘I don’t wanna stop using.’ So, Neil, Chris [Pyle, drummer] and I played the last show at 7th St Entry, and the next day we drove back to Virginia.”

Hagerty called time on both the band and the relationship. Complicating matters, a year earlier Herrema and Hagerty had actually married, somewhat prosaically, so that he could access her health insurance to get $20,000’s worth of new teeth. This came to haunt Herrema, as Hagerty, fearing she was going to OD, turned up at the hotel she’d shacked up in, to get her sent to a psychiatric hospital. “I punched him in the face,” she recalls, “and he waved our marriage contract at me – in American law, a husband can control their spouse, so he got me committed. It wasn’t a good time. (Long pause) We always knew there would come a time for separation, because Neil always wanted kids, and I always didn’t want kids.”

In the divorce, she says, “He signed Royal Trux over to me, lock, stock and barrel. With Neil, it was an all-or-nothing proposition, and it didn’t exist for him any more.”

FOR THE NEXT DECADE and a half, they lived entirely separate lives, she in LA’s suburban Orange County, he in Denver, Colorado, where he has a wife and 10-year-old daughter. Hagerty’s recordings with The Howling Hex often seemed vindictively to avoid Trux’s astral riffage, while Herrema’s more Trux-like outings as RTX and Black Bananas only lacked his extraordinary playing.

“We never spoke,” she says, laughing admiringly at his single-mindedness. “He wrote me three e-mails in 12 years, to tell me when each of the cats had died.”

The next e-mail landed in 2012: Hagerty was involved in a conceptual live performance of Twin Infinitives in Brooklyn, and he contacted her, he says, “because I had to make sure she knew I wasn’t doing it to undermine her.”

“That was the first time I knew, he still believes in it,” says Herrema, but there was no further dialogue until a “substantial” offer came in to reunite for California’s Berserktown ’15 festival.

“I was mid-tour, and frankly felt I could do with the money,” admits Hagerty. There followed 20-odd appearances, and, after a bad falling-out with Drag City over streaming rights, Herrema hustled a new deal with Fat Possum, the Oxford, Mississippi-based indie, whose roots were in documenting veteran bluesmen.

“It got pretty tame around here, after R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough passed away,” says the label’s maverick boss, Matthew Johnson. “Indie rock is all dentists’ kids these days, but with Neil and Jennifer, it’s like doing a ski course that’s way out of your league. You wouldn’t be surprised if somebody said, ‘Oh, their car just got hit by a meteor!’”

Indeed, as MOJO watches Royal Trux fall apart before his very eyes – again! – the only question is how they stopped fighting long enough to finesse their comeback record, whatever it’s ultimately called.

Shrugs Hagerty, “She worked on some stuff, I worked on some stuff, then you throw it in a box and shake it up. That used to be in the same house, in the same room – now it’s just using the internet. It’s pretty cool, man. We send each other stuff and we’re right on the same wavelength.”

With an engineer refereeing, they somehow got through two weeks’ recording in California in June ’18, but Hagerty claims not to have listened to any of the advance mixes e-mailed to him thereafter, or read any attendant messages. Miraculously, the album is a corker, delivering mangled riffs, yowling choruses and sublimely strange solos as if Y2K were but yesterday.

The morning after our interviews – eventually conducted individually – a barrage of texts arrives from both parties. From Herrema: “How was your interview with him? Anything positive, or all bitter and bile? He’s been e-mailing me, I’m not responding. He can sit with his bullshit in silence awhile.”

A little later, from Hagerty: “Listen, I told Jennifer I said nasty stuff about her. Maybe in her hour of need you might soften some of my most thoughtless insults to her. She is unwell.”

By the time MOJO’s plane touches down in London, however, there’s been a détente.

“Neil is back and acting as if all was/is peaches,” writes Herrema. “I went with it! I like peaches!”

For 30 years, Royal Trux have specialised in ripping rock’n’roll apart. Maybe their fighting is essential to the process. “If you took it away, I wonder what would be left,” says Fat Possum’s Matthew Johnson. “There’s almost something sacred about it.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 304 of MOJO

MAIN IMAGE: GETTY