Mojo

FEATURE

Oh Well…

In 1968, Fleetwood Mac had the lot – fame, fortune, international success – and their leader Peter Green a reputation as the most soulful of guitar gods. And then, fuelled by idealism, LSD and a purist mentality, Green set about destroying everything they had. Behold the remarkable story of Mac’s first incarnation and the rise, fall and rise again of one of Britain’s greatest musicians.

Words: Johnny Black & Martin Celmins

It’s mid-winter 1968. The five members of Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac are huddled together, holding hands on the floor of the Gorham Hotel on West 55th St, New York, scared shitless. “I looked at Peter,” recalls Mick Fleetwood, “and saw him dead, a skeleton without flesh, but moving. I couldn’t even look at the others. It was a horrible, helpless feeling. We’d heard about bad trips and damaged chromosomes and permanent LSD psychosis but we hadn’t the foggiest notion what to do. We began to weep and blubber for help.”

For Mick Fleetwood and John McVie this first experience of LSD, though terrifying, was something they could handle. For Peter Green it was the opening of the doors of perdition, a path that eventually led him to prison, psychiatric hospitals and two decades of reclusion and mental health struggles.

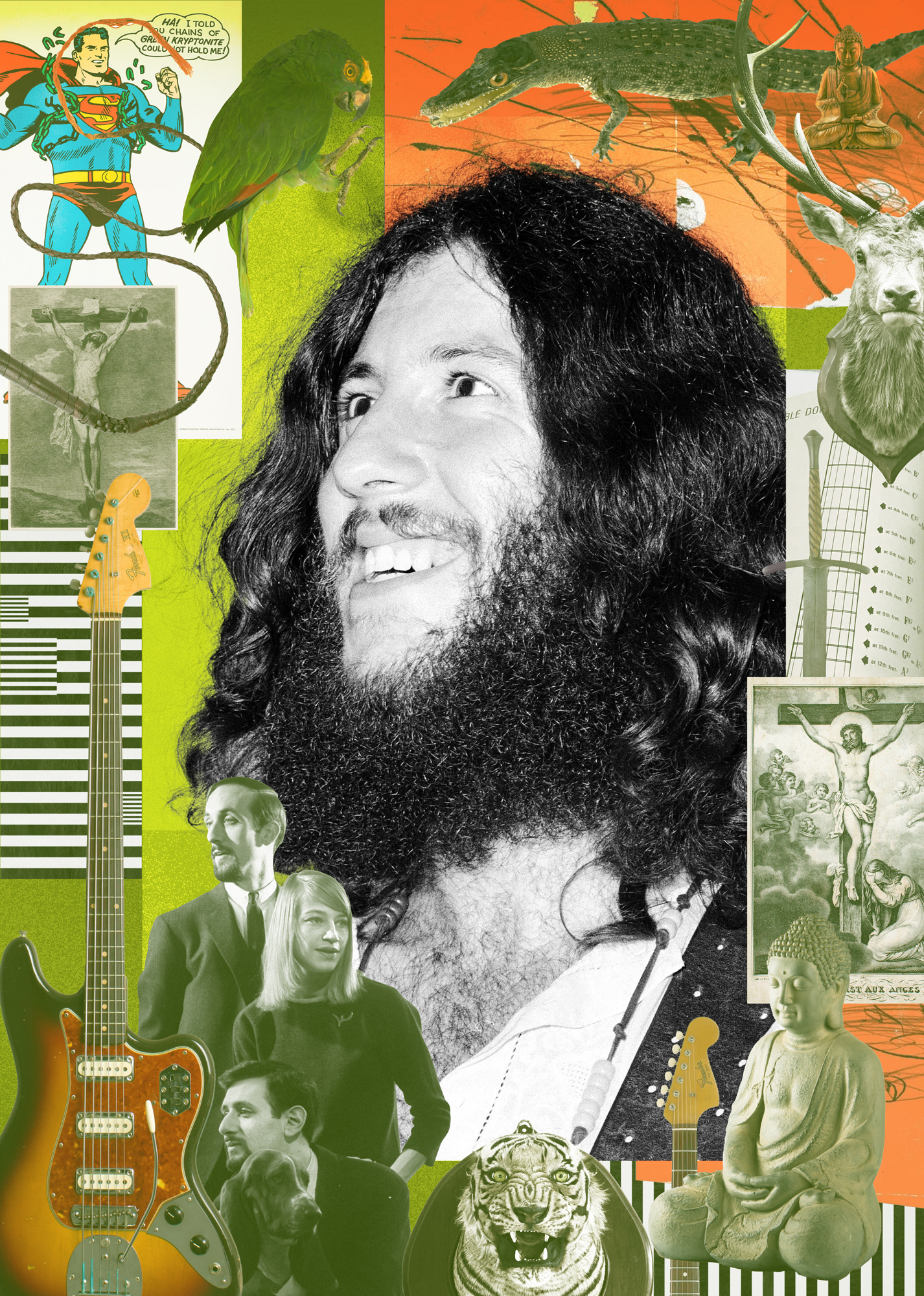

Curious habit: Peter Green in his “monk’s robes” performing Oh Well with Jeremy Spencer on guitar, October 1969.

Although formed less than 18 months earlier, Fleetwood Mac were already Britain’s premier blues attraction. An impressive debut album plus two hit singles, Black Magic Woman and Need Your Love So Bad, had quickly leapfrogged them past such rivals as John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Alexis Korner.

Born Peter Greenbaum in Bethnal Green in 1946, he was a sensitive child in whom music had always inspired powerful emotions. He would burst into tears when he heard the theme from Disney’s Bambi, because he couldn’t bear to remember the suffering of the baby deer. He was sensitive in other ways too. As a Jewish kid in London’s tough East End, he was constantly teased and taunted and the scars remained into adulthood. Sandra Elsdon, the Black Magic Woman of the song, clearly recalls him sobbing as he spoke of the pain of growing up. “To me, those are Peter’s blues,” she told Martin Celmins, who penned his authorised biography. “The blues for him are Jewish blues.”

Certainly by mid-1966, when Green replaced Eric Clapton in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, his blues were unique. And in September 1968, on Fleetwood Mac’s second album, Mr. Wonderful, he explicitly referred to his childhood traumas with his song Trying So Hard To Forget. As Mick Fleetwood recalls, it was “Peter Greenbaum baring his soul about growing up in Whitechapel, London’s Jewish ghetto. For almost the first time I could feel the pain, hurt and sense of loss that Peter was expressing through the solace of the blues.”

It was his first step from black blues interpreter to white blues originator. From here on, his songs almost invariably documented his troubled state of mind.

That same summer of ’68, the Mac undertook their first American tour. In San Francisco they hung out with the Grateful Dead, whose legendary acid-chemist Augustus Stanley Owsley III offered them tabs of his superior quality LSD. “We politely thanked him and said no,” remembers Fleetwood. “We were scared of LSD. In fact, we were scared enough just being in America.” But Owsley did secure a promise that, when they returned, they would sample his wares.

Come the first week of December, Fleetwood Mac were in New York at the start of a 10-week US tour and, for the first shows, they were to support the Dead at the Fillmore East. This time, as agreed, they said yes to Owsley. “We figured he made the best, most pure LSD available. We all wanted to try it and, if not his, whose?” says Fleetwood. “We didn’t want to play on acid, so we took it back to our usual New York digs, the Gorham Hotel on West 55th St.”

It was not what they expected. After an hour, the group experienced a communal anxiety attack which turned into a nightmare trip. At their lowest ebb, the phone rang. “It was Owsley, calling to see if we were enjoying ourselves.” Over the phone, Owsley talked them down, issuing soothing words and firm directions until the experience changed to something more pleasant – a sensation of flying.

Meanwhile, the languidly drifting instrumental single Albatross, a radical departure from the pure blues with which the group was identified, was soaring up the British charts. Before they returned to England, however, a follow-up single was recorded in New York – Man Of The World. Once again, despite his group’s increasing success, the lyric revealed Peter’s inner turmoil. As he told one interviewer at the time, “It’s very sad. It’s the way I felt at the time. It’s me at my saddest.”

Yet, according to producer Mike Vernon, “during the recording of Man Of The World, Peter was very focused. He knew exactly what he was trying to achieve and set about it in a thoroughly professional way. If they were doing acid at that point, there was no sign of it.”

Out of the studio, however, those around him had already begun to notice that something was up. Tour manager Dennis Keen remembers Green telling him, “I feel like a washing machine. Just plug me in and I’ll play.” Mick Fleetwood recalls conversations, even then, in which “he’d become obsessive that we should not be making money. He wanted to give it all away.”

When Fleetwood Mac returned to England, Green’s friend Paul Morrison observed that, “Peter was unhappy about something… he was beginning to feel detached from the whole Fleetwood Mac process.” The detachment expressed itself clearly during the recording of the next album, Then Play On, on which Green spent most of the time working on his own, laying down multiple guitar parts and even drum patterns. The rest of the band were, effectively, frozen out.

“I was worried about what I was becoming and it got into the newspapers. I was boasting about being righteous because I was on mescaline and I was feeling holy and compassionate.”

Peter Green

Man Of The World was released that April 1969 and followed Albatross to the higher reaches of the singles chart. Speaking of their tour with the Dead, Green told Beat Instrumental that “I miss those beautiful people. I must say my eyes were opened to a lot of things.” With evident enthusiasm, he showed the interviewer a book he had purchased. Titled Words Of Wisdom, it was a compendium of such dimestore mystical insights as “Men are born with two eyes but with one tongue in order that they should see twice as much as they say” and “To know what you know and what you don’t know, is the characteristic of one who really knows.”

By now Green was questioning his most fundamental beliefs and all of them came up wanting. Although Then Play On had proved to be their most successful album yet, Green was slipping further into his personal slough of despond. One night, after a show, he told Fleetwood “I want to find out about God. I want to believe that a person’s role in life is to do good for other people, and what we’re doing now just isn’t doing shit.” Nothing Fleetwood said could pull him from his depression, and after a while they lapsed into a long awkward silence.

Finally, Green stood up to go and said, “Sometimes I think music is everything, other times I don’t think it’s anything. I don’t give a shit about the money. I’m in a terrible state of ‘don’t knows’ right now.” He soon renounced his Jewish faith in favour of a mixture of Christianity and Buddhism, and took to wearing a white monk’s robes on stage with a huge crucifix dangling at his neck.

In October, once again, Green laid his cards on the table in the shape of a song, Oh Well. “I can’t help about the shape I’m in…” he declared in the first line then, even more revealingly, launched into the second verse with “Now when I talked to God…”

Virtually a solo performance, it was yet another radical departure from any previous Fleetwood Mac release. The others in the group each laid a £5 bet with him that it wouldn’t be a hit, but it shot to Number 2. Green appeared on Top Of The Pops wearing his monk’s robes and crucifix. “That wasn’t theatre,” says Fleetwood, “that was him. He was on a crusade in his mind and we had no idea how deep he was really getting into it.”

“I was worried about what I was becoming,” Green says now, “and it got to the newspapers. I was boasting about being righteous because I was on mescaline and I was feeling holy and compassionate.” So compassionate, as Mick Fleetwood recalls, that having been moved to tears while watching TV reports of starving children in Africa, Green sent a £12,000 donation to Save The Children.

In early 1970, Fleetwood Mac flew to America for another tour. When they opened for the Dead at the Warehouse in New Orleans, Owsley re-entered the picture, spiking the venue’s water fountains with acid. Mick Fleetwood’s girlfriend of that period, Jenny Boyd, remembers, “Peter couldn’t even play that night because he was so high. Danny was weird too and Mick looked like a goblin playing drums. It was a very freaky evening.”

Usually, after a show, the Mac would spend the night socialising with the Dead at their hotel, but on this occasion, being too stoned to function, they returned to their own hotel. Next morning they learned that in the night, as recorded in the Dead’s song Truckin’, the Grateful Dead’s hotel had been raided by police pursuing Owsley. Had Fleetwood Mac been there, they would undoubtedly have been arrested and deported.

World in harmony: Peter Green, London, 1970.

While in Sweden, in April, according to Clifford Davis, Green sat down beside him in the tour bus and announced he was leaving. “Apart from anything else,” he said, “I’ve had enough of these shits.” Then he walked to the front of the bus and broke the news to the group. “He left in a very responsible fashion,” points out Mick Fleetwood, referring to Green’s promise to honour all existing live commitments, “but behind all that was this seething emotional disturbance.”

At one of those final shows, at the Lyceum in London, Green was seen backstage, tripping on acid, attempting to set fire to the amps. He officially left the group on May 31, 1970 as Green Manalishi shot up the charts. Within a month, Green told Beat Instrumental, “The most admirable and best thing a man can do on this earth is to try and make an effort to be like Him – like God… a lot of people are afraid to say it, but I feel I am guided by the Good Spirit, or God, if you like.”

Towards the end of that year, fulfilling his contractual obligation to Warners, Green released his first solo album, The End Of The Game. “That was my LSD album,” admits Green now. “I was trying to reach things that I couldn’t before but I had experienced through LSD and mescaline.”

One observer at the studio, the guitarist Jon Morsehead, noted that “Peter was very much in his own corner and would start playing. Things got going, riffs would change and it went on hour after hour.”

And, as revered R&B pianist Zoot Money remembered, nothing was prepared in advance. “We just played away and took the tapes and put it all in some sort of order. It started around 10 in the evening and it was heads down until 4am. Then it was like, ‘Right, ta-ta, hope that was enough.’”

Meanwhile, to fill the gap left by Green, Fleetwood Mac had drafted in the UK’s most prominent female blues performer of the time, Christine Perfect (aka McVie). In January 1971, their first album together, Kiln House, was climbing the US charts. With half the band already flying courtesy of a considerable intake of mescaline, they boarded a plane for Los Angeles for their next US tour. Jeremy Spencer predicted ominously that something was going to happen – that there was darkness in Los Angeles. “We landed just after the big earthquake,” says Christine McVie. “I remember the sky being yellow and Jeremy saying, ‘I don’t have to be here. I don’t want to be here.’ No one thought anything of it. We got to the hotel, Jeremy went out for some magazines, and he never came back.”

Outside the head shop where Spencer bought his magazines, he had encountered a recruiting cell of the Children Of God religious cult and, ripe for the picking, went off with them. Cancelling the gig, the group began a frantic search of LA’s religious communes and eventually located Spencer in a warehouse. “His head was shaved,” remembers Mick Fleetwood, “and he had a different name. Basically, he was like a zombie.”

With its eerie echoes of Peter Green’s condition, Spencer’s defection came as a shock to the band. But, on a purely practical level, without him the set was six songs too short. “We called Peter and begged him to help us complete the tour rather than being sued,” remembers Christine. “Peter came over and the remainder of the tour was totally instrumental. Peter refused to sing. We did a version of Black Magic Woman that lasted 45 minutes.”

Dennis Keen was shocked by this new Peter Green. “His personality had totally changed from a kind, considerate guy to an angry animal. He didn’t like anything or anybody.”

Show-biz blues: with Green gone, a new Mac arises (from left) Danny Kirwin, Christine McVie, Mick Fleetwood, Jeremy Spencer, John McVie.

For most of the ’70s Green was unable to pull himself back to anything approaching normality. In 1972, when Les Harvey of Stone The Crows was tragically killed by electrocution, Green was offered the job as his replacement. He went through all the rehearsals and then, two days before the first gig at the Lincoln Festival, he rang to say he wouldn’t be able to make it.

Later that year he moved to Israel and lived for a while on the Kibbutz Mishmarot, near Tel Aviv, telling his girlfriend of the time only that “he wanted to be near his people.” He was back in England by 1973 and took a number of menial jobs – cemetery gardener, pathology lab assistant, hospital orderly. He moved from house to house, sleeping on the floors of various friends including Thin Lizzy guitarist Snowy White. “He’d come round and borrow my car, or sleep on the settee,” he recalls. “He gave me all his gear, all his records, old reel-to-reel tapes of him working out Oh Well with different lyrics. And he left his guitar with me. Suddenly one day he came along and wanted everything back.”

Green then made White drive him to an Oxfam shop on Hammersmith roundabout where he gave all his gear away. “I wasn’t surprised,” says Snowy, “but I thought it was a shame.”

Green had put on considerable weight by 1974 and was taking medication to counter the effects of his deteriorating mental state. Michelle ‘Mitch’ Reynolds, who was by now his manager, remembers that after a long period of simply being very withdrawn, Green began to suffer hallucinations and his emotions see-sawed erratically, as a result of which he was hospitalised in West Park, Epsom. When his condition failed to improve he was given a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. This drastic treatment frightened him, but it stabilised his behaviour by reducing him to a level of docility in which he appeared to be almost in a trance.

In January 1977 he returned from a spell in Canada and rang former manager Clifford Davis. “I wanted some money from him ’cos I was living in people’s houses or hotels and things,” remembered Green. “He said he hasn’t got any money; our accountant David Simmons has got it. I said, ‘Look, I’ll shoot you’ – I recently bought a gun from Canada. It was like a fairground rifle, pump-action thing, made of nickel.”

Green insists that this threat was made jokingly, but Clifford Davis was taking no chances. He called the police and Green quickly found himself in Brixton Prison.

By the time this story made the national tabloid press, late in January 1977, it had been embellished. Green had, said the papers, threatened accountant David Simmons with a shotgun when he turned up to deliver a £30,000 royalty cheque. Simmons now insists that no such incident ever took place and Green’s version of events seems to be substantially accurate.

Nevertheless, his behaviour was clearly still erratic and, following a diagnosis of schizophrenia, Green was moved to The Priory, the private clinic in London famous for treating rock royalty. It was here, at last, that he began to return to some semblance of normality.

Within months, while Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours began its 31-week stint at the top of the American charts, Green was able to check out of The Priory and seemed reasonably content with his lot as a musician in retirement. It was not to last.

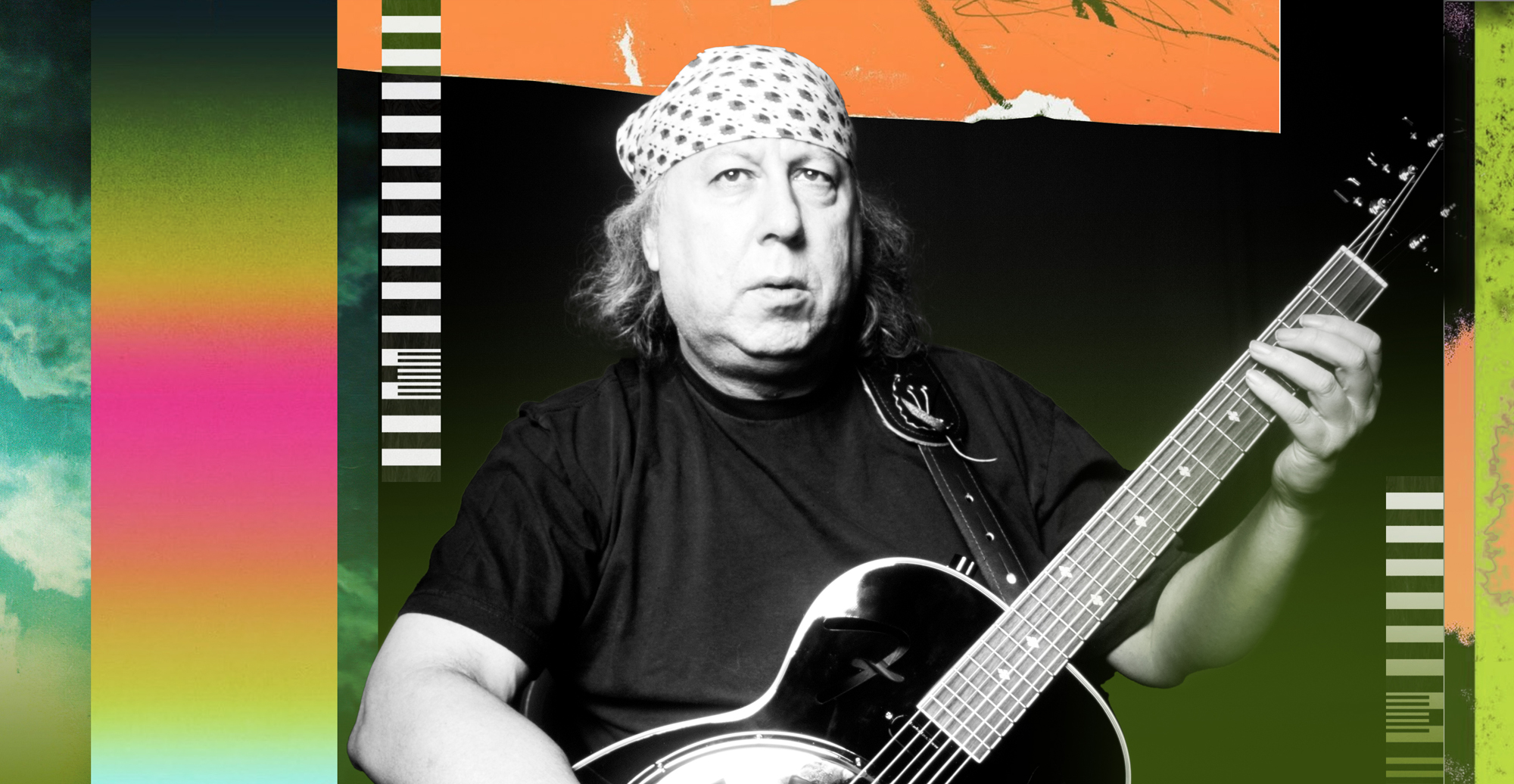

Resurrection: Peter Green on-stage at Fairfield Halls, Croydon, October 27, 2002.

Peter Green’s brother Michael had recently started working as a promotions man for PVK Records, a small label owned by Peter Vernon-Kell. Briefly a member of The Detours (the group which evolved into The Who), Vernon-Kell was now a successful businessman, living in a large Twickenham residence complete with Rolls-Royce Corniche and racing whippets.

At Vernon-Kell’s suggestion, Michael took Peter to the office one day. Although Green was now better than he had been for some while, in an interview with the NME Vernon-Kell described him at that first meeting as being “in a diabolical state. It was like something out of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. He was eating with his hands and everything. In the loony bin they’d pumped him up to his eyeballs with drugs. It was disgusting. That’s no way to treat a person.”

Neither this, nor the fact that Green had not played guitar for over five years, deterred Vernon-Kell from offering him a recording deal. Work on the first album progressed at a leisurely pace. The approach was to surround Green with sympathetic musicians, put them in a studio and wait to see what developed.

Early results were encouraging but then, out of the blue, Green met and fell in love with Californian fiddle player Jane Samuels. Born Jewish, Samuels had converted to Christianity and she successfully brought Peter to the faith. They were married in Bel Air on January 4, 1978 and had a daughter, Rosebud. During this time in Los Angeles, Green also fell back in with Fleetwood Mac and began to substitute considerable snorts of cocaine for the medication he had been prescribed. This may help account for the volte-face in which he came to believe that his new wife had made a covenant with the devil and was now attacking him from within.

Meanwhile, with what seem to have been the best of intentions, Mick Fleetwood persuaded Warner Brothers to offer Green a $900,000 deal for four albums over a four-year period. It was exactly the wrong move. Had it happened, the deadly cocktail of success and drugs that had fuelled his first breakdown would have been in place again. Fortunately, says Peter Vernon-Kell, Green was canny enough to turn it down.

Parting from his wife, Green returned to England somewhat the worse for wear and set to work again on what would become the first PVK album, In The Skies. Peter Vernon-Kell has stated that during recording, Green was “as sharp as a razor blade. When he first started playing he was very insecure, but he slowly came out of it and by the time he started recording, he was totally on the ball.” Snowy White, who played on the album, disagrees. “Sharp as a razor? No, he wasn’t. He played quite well but he was a bit out of tune and never took control of the sessions. He wasn’t back on form and was hardly involved with the end result. He just played and went.”

Green’s continued obsession with religion is evident in the album’s big production number, Apostle. He had returned to the Jewish faith, reverted to his real name, Greenbaum, and talked of forming an all-Jewish band to play Jewish music. “Sometimes it means a bloody hell of a lot and sometimes we wish we were something else,” he told one interviewer. “I’m glad I’m Jewish. It feels like a nice medium between the ordination and whatever that might mean to everyone. I love being Jewish. I think it’s a good obedience test. I fail dismally.”

When the album appeared in May, Green was anxious about facing the media and blew out an Whistle Test appearance along with other TV interviews. The level of concern of some PVK staff for their delicate charge was made clear by one who told NME writer Steve Clarke that when Green was in one of his funny moods, he was liable to “walk off and lose his mind again. Shove him in a boozer and he’ll be all right.” Even so, the album just missed the UK Top 30 and reportedly sold 800,000 copies in Germany where it was hailed as the return of a long-lost guitar genius.

During recording of a second PVK album, Little Dreamer, Peter clearly still had issues. “He arrived at the studio with these incredibly long nails,” recalls guitarist Ronnie Johnson. “The producer was frantically trying to cut them so Peter could play.”

The ’80s were even less fruitful. After a third PVK album, Whatcha Gonna Do?, the association with Vernon-Kell ended, though Green would go on to release two more solo LPs, White Sky and Kolors, plus a 1985 album called A Case For The Blues by Katmandu, a group he formed with Mungo Jerry’s Ray Dorset and Vince Crane of Atomic Rooster.

By the end of the ’80s, however, the tabloids were reporting that Green had been sleeping rough in Richmond. His guitars had been stolen, he had been physically beaten and it appeared that, with no further down to go, his story might be close to ending.

“I wanted some money from our old manager ’cos I was living in hotels and things. He said he hadn’t go any money, so I said, Look, I’ll shoot you. I had recently bought a gun from Canada.”

Peter Green

But fate was not yet ready to leave Green alone. In 1992, a man walked into a guitar shop owned by David Edwards, a member of a band called National Gold. The man claimed to be Peter Green. He was not. He was Patrick Harper of Hockley, Essex, known locally as The Egg And Potato Man.

Nevertheless, Edwards, who had met the real Green about 10 years earlier, believed him. “We became good friends. I played him our tapes and he said they were brilliant.” Harper convinced the whole National Gold band that he could get them a recording deal.

For a further two years, The Egg And Potato Man continued his bizarre impersonation. He was convincing enough to secure the involvement of former Shadows drummer Tony Meehan and Queen’s Roger Taylor in a proposed ‘comeback’ album. The deception was only uncovered when the real Peter Green’s brother Michael learned of what was going on and confronted Harper.

By 1996, Green was slowly getting back on track. According to his friend Nigel Watson, sister of Mitch Reynolds, his skills were returning. “At first, when he played, you could see that his mind wanted to do more than his hands could. He got in a fluster but, after three or four weeks, that went.” Watson, drummer Cozy Powell and bassist Neil Murray became his backing band The Splinter Group, with whom he’d record seven blues-based LPs. The last, Reaching The Cold 100, released in 2003, would be the last studio album he’d make.

His final years until his death in July 2020, aged 73, saw him perform live on and off as Peter Green And Friends, thrilling those wishing to see a ’60s guitar legend in action. Three years after his passing, Bonham’s auctioned off the 150 or so guitars and other instruments he’d accumulated, together with other memorabilia. The man who’d wanted to give everything away hadn’t died completely empty handed.

Thanks to Bob Brunning, David Costa, Keith Altham, Dean Nelson, Steve Clarke, Brian Hogg, Mike Vernon, James Campbell, Charles Measures.

IMAGES: GETTY