Mojo

FEATURE

CARELESS WHISPERS

After Peter Green quit in 1970, Fleetwood Mac embarked on a five-year struggle to regain their creative mojo – a turbulent quest that took them to the edge of extinction. But in 1975, they hooked up with pair of glamorous Californian folk singers and, from an abyss of betrayal, obsession and narcotic excess, came the magical Fleetwood Mac and 1977’s mega-selling Rumours. Older, wiser and back for one more defiant tilt at the world’s stadia, in 2012 MOJO found the group still wrestling with their ’70s ghosts. “We were lucky to get out alive,” they say.

Words: Mark Blake

THE CIRCULAR CAPITOL RECORDS tower at 1750 Vine Street, Los Angeles, resembles a 13-storey stack of vinyl against the Hollywood skyline. A landmark since the ’50s, it was Fleetwood Mac guitarist Lindsey Buckingham’s destination one afternoon in December 1976.

When Buckingham and his girlfriend, vocalist Stevie Nicks, joined Fleetwood Mac two years before, they were struggling to pay the rent. But 1975’s platinum-selling Fleetwood Mac album had transformed all their lives. “Now Lindsey and I had money,” says Nicks. “We were rich.”

That afternoon, Buckingham was heading to Capitol to help master the next Mac album, Rumours. As he drove down Hollywood Freeway, his then-plentiful rock star hair was, he admits, “blowing in the breeze”. But he hadn’t yet traded in his $2,000 BMW or, like Nicks, splurged on a wardrobe of fancy new clothes. Then, as now, Lindsey Buckingham was all about the music.

The car radio was tuned to LA’s progressive rock station KMET, which was playing Rumours’ lead single Go Your Own Way. As the song faded out, the DJ started speaking. “He was this legendary DJ in LA called B. Mitchel Reed,” says Buckingham now. “And he said, ‘That was the new single from Fleetwood Mac… Nah… I’m not sure about that one.’”

As soon as he reached the studio, Buckingham was on the phone. “Being the cocky young guy I was, I got B. Mitchel’s number. I said, What didn’t you like? And he replied, ‘I couldn’t find the beat.’ The thing is, I’d put this disorientating guitar part on the song at the 11th hour. And know what?” He laughs drily. “I sort of know what he means.”

A month later, Rumours was at Number 1 on both sides of the Atlantic. Officially the eighth biggest-selling album of all time, it remains one of the alchemical works of rock and pop, transcending its mid-’70s West Coast milieu to bewitch three generations of fans and serve as a touchstone for musicians from myriad genres.

For punk-era firebrands Rumours came to symbolise everything they opposed, but today’s listeners look past its glint of sunshine on silver coke spoons. Buckingham and Nicks may have been Fleetwood Mac’s golden Californian couple, but there was always something subversive and, perhaps, perversely British at the band’s core. For each of Rumours’ flawless harmonies there’s a “disorientating guitar”. For every sweet melody, there’s a lyric inspired by dark emotions and psychic trauma. Divorce, drugs and stir-craziness all swirled into its creation.

For Fleetwood Mac, the road to Rumours was marked by maddening setbacks and incredible serendipity. Then, when the band reached their destination, they found themselves on the brink of collapse. As drummer Mick Fleetwood says: “We were lucky to get out alive.”

“The engineer Keith Olsen put on two tracks by this duo he had recorded. By coincidence they were in the studio next door. I have a vague memory of a pretty blonde girl…”

Mick Fleetwood

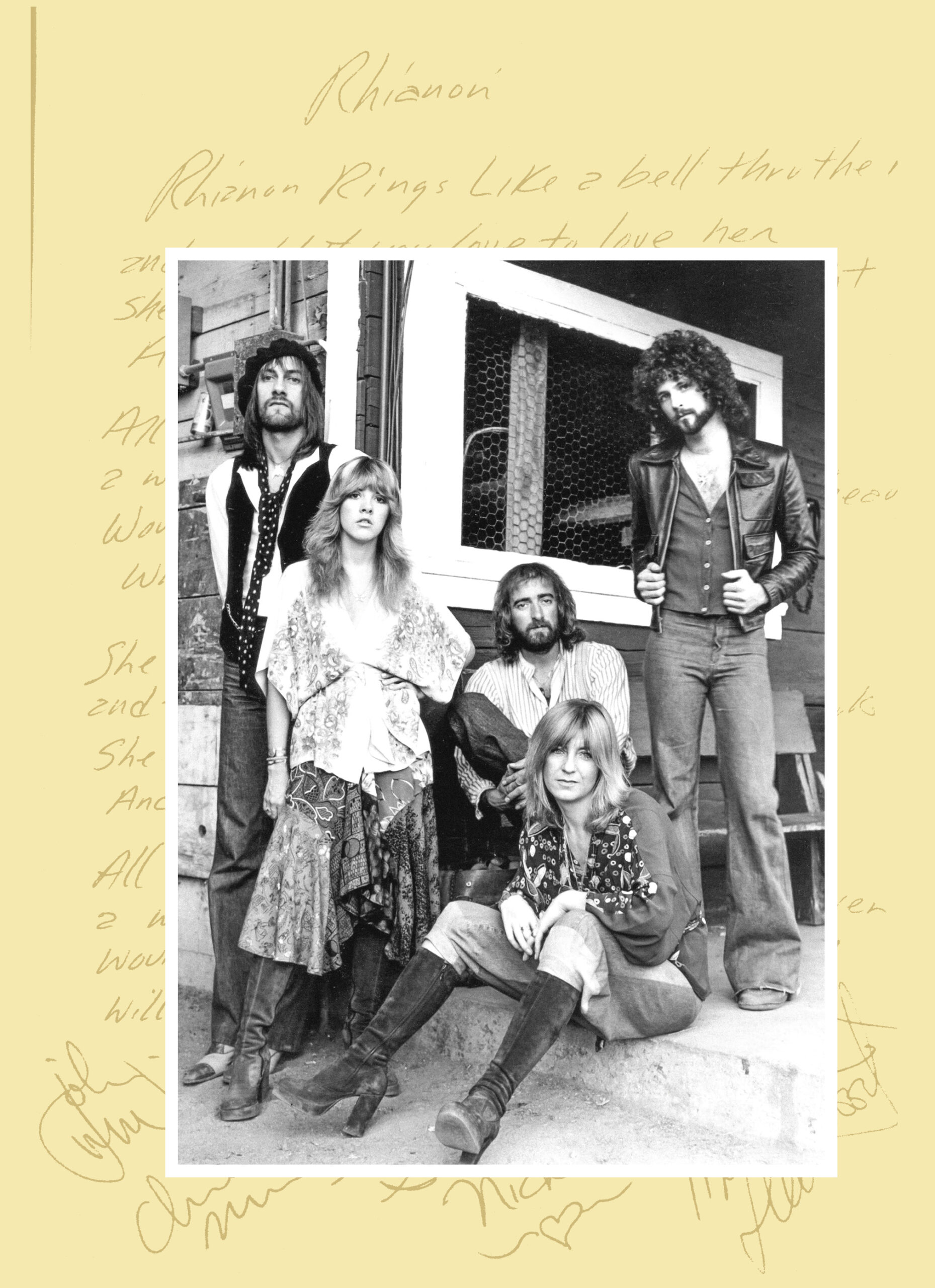

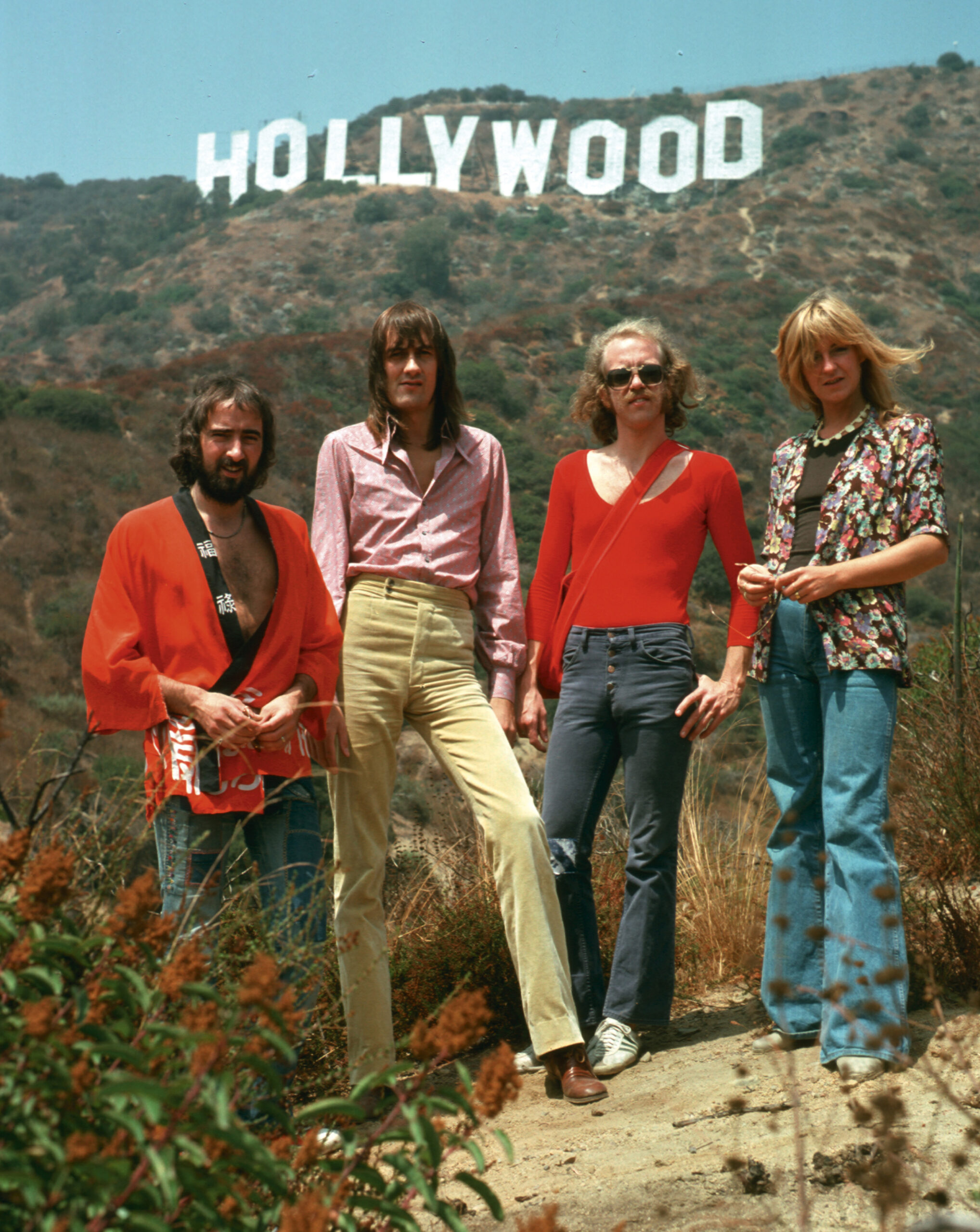

Warm ways: Stevie Nicks (second left) and Lindsey Buckingham (far right) bring some California dazzle, 1975.

WHEN I INTERVIEW THE BAND AT the end of 2012, Rumours is being readied for reissue with an extra disc of unreleased alternate takes, plus a promo film – the notorious Rosebud – that preserves the group in the amber of their late-’70s mega-fame. And in February, the regrouped Mac will begin rehearsals for a world tour. “We work when it feels right,” says Fleetwood today. “The tempo is dictated by all of us.”

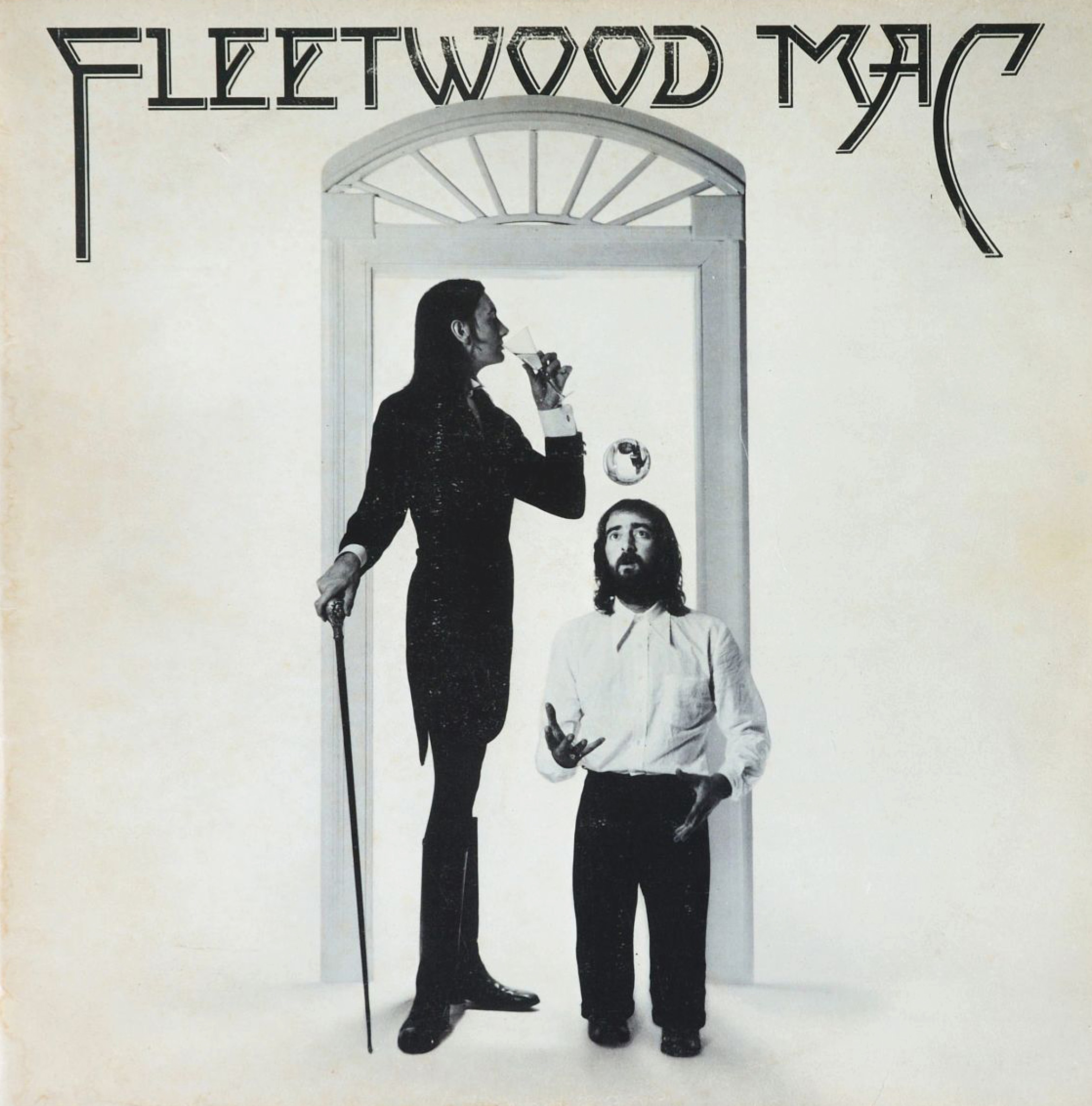

Home for the 65-year-old Fleetwood is the Hawaiian island of Maui, where he has recently opened a beachside restaurant with a picture-postcard view of the ocean. Handily, the ‘Mac’ in Fleetwood Mac, 66-year-old bassist John McVie, lives on the neighbouring island of Oahu. Nowadays, Fleetwood, with snow-white beard, ponytail and dandyish waistcoat, resembles a retired wizard. Flat-capped McVie, a keen sailor, has turned into a grizzled sea captain.

By the time they’d made Rumours, Fleetwood and McVie had already weathered many storms. Fleetwood Mac were stars of the late-’60s British blues boom. But by 1971, they’d burned out three gifted guitarists, Danny Kirwan, Jeremy Spencer and, most famously, founder member Peter Green, the star of the UK hits Man Of The World and Albatross.

Their luck changed with the arrival of former Chicken Shack vocalist/pianist Christine Perfect. She married McVie and joined Fleetwood Mac for 1970’s Kiln House LP. A year later, they’d hired Californian vocalist, guitarist and songwriter Bob Welch. Welch wrote what Fleetwood describes as “these lovely kooky songs” for 1971’s Future Games, the following year’s Bare Trees, and 1973’s Penguin and Mystery To Me. Folk, boogie and West Coast pop began to usurp the blues. Slowly, Fleetwood Mac were feeling their way towards a sound that would make them spectacularly rich and famous.

Touring America doggedly, the band sold just enough records, says Fleetwood, “to pay the Warner office’s lighting bill”. Back home in England, though, they were forgotten. When their 1969 hit Albatross was re-released in June ’73, a Top Of The Pops host told viewers that Fleetwood Mac had since split up.

“I have no memory of meeting Mick that day. And we were not high on drugs. Lindsey and I had no money for drugs back then.”

Stevie Nicks

In October that year, Mick Fleetwood cancelled a US tour after discovering that band guitarist Bob Weston was having an affair with his wife Jenny Boyd. To honour the dates, the group’s manager Clifford Davis put together his own version of Fleetwood Mac made up of hired hands. “It was a murky time,” sighs Fleetwood. “We had to get over to the States and prove that we were the real thing.”

In spring ’74, Fleetwood, Welch and the McVies took the momentous decision to leave England and move to Los Angeles. With the genuine article on their patch, the ‘fake’ Mac didn’t last, and the ‘real’ group’s next album Heroes Are Hard To Find was the first to crack the US Top 40. Fleetwood immediately began thinking about making a follow-up. “I was in this rustic hippy supermarket in Laurel Canyon, when I ran into this guy who worked for Sound City studios out in the Valley,” he recalls. “I was looking for somewhere to make the next album, so I agreed to check out his studio.” That afternoon, Fleetwood drove to Sound City in Van Nuys and was introduced to engineer Keith Olsen.

“Keith put on two tracks by this duo he’d recorded,” remembers Fleetwood. “It was just to demonstrate the sound of the studio. But it made an impact on me. By coincidence, the two of them were in the studio next door. I have a vague memory of a pretty blonde girl.”

“It’s the strangest thing,” says Nicks, “because I have no memory of meeting Mick that day. And we were not high on drugs. Lindsey and I had no money for drugs back then.’

Fleetwood left the studio with Keith Olsen’s phone number and headed back out on tour. “And after the last gig Bob Welch told us he wanted out,” he sighs. “I already knew he wasn’t super-happy. He had concerns with his marriage, but I also think he was heartbroken about the amount of work we’d done for so little reward.”

The rest of the band were crestfallen, but Fleetwood had an idea. “When Keith played me those Buckingham-Nicks songs, the music had absolutely resonated with me. But it wasn’t until Bob quit that I realised how much. I’d heard something in Lindsey’s playing that reminded me of Peter Green. Straight away, I said, I need to find those people.”

Fleetwood called Olsen on New Year’s Eve 1974. “Mick told me Bob had left and asked me the name of the guitarist he’d heard at Sound City,” recalls Olsen. “I told him it was Lindsey Buckingham, but that he and the singer Stevie Nicks came as a pair. He asked me to ask them if they would consider joining the band. So I took my date for New Year’s, drove over to Lindsey and Stevie’s place, and spent four hours sat in their bedroom convincing them to join Fleetwood Mac.”

STEVIE NICKS AND LINDSEY Buckingham’s story is one of the great rock’n’roll fairy-tales. Thirty-five years on from Rumours, neither can fully escape the legacy of their ancient love affair.

Today, Buckingham lives with Kristen, his wife of 12 years, and their three children in an elegant estate in Westwood, California. Wiry and lean, only the silver flecks in his hair betray his 63 years. In conversation, Fleetwood Mac’s musical perfectionist is as meticulous answering questions as he is when making a record.

Nicks, too, resides in California, but recently downsized from a palatial villa in Encino with a two-storey waterfall in the front entrance. Her latest solo tour finished just three days ago, and her speaking voice sounds huskier than ever. “Stevie doesn’t stop working,” forewarns Fleetwood. “She’s turning into Edith Piaf.”

In 1997, your writer joined Fleetwood Mac on tour in Detroit. In a hotel bar after the show even Fleetwood and John McVie smiled at the sight of Nicks gliding through the lobby, surrounded by a phalanx of handmaidens. In conversation, however, she’s un-starry, direct and mischievously funny. “Have I exhausted you yet, dear?” she purrs, after one especially lengthy answer.

Buckingham and Nicks met in 1965 when Phoenix-born Stevie transferred to Lindsey’s high school in the Bay Area suburb of Atherton. She was 17; he was 16. Her grandfather, Aaron Jess Nicks Snr, was a Country & Western singer, and Stevie, too, had begun singing and writing country songs. Buckingham was the third son of a San Francisco coffee magnate. He joined his first band, an acid rock group called Fritz, in 1966. Nicks became their lead singer two years later. By 1971, though, they were still searching for a deal.

““I wouldn’t say that I had to be persuaded to consider joining Fleetwood Mac, but there was some ambivalence.”

Lindsey Buckingham

Keith Olsen was interested and cut a demo for Fritz. But he really wanted to work with Buckingham and Nicks, not the whole group. The pair agreed to the split. “All through Fritz, Lindsey and I were dating other people,” says Nicks. “I’m not sure we would have even become a couple if it wasn’t for us leaving that band. It pushed us together.”

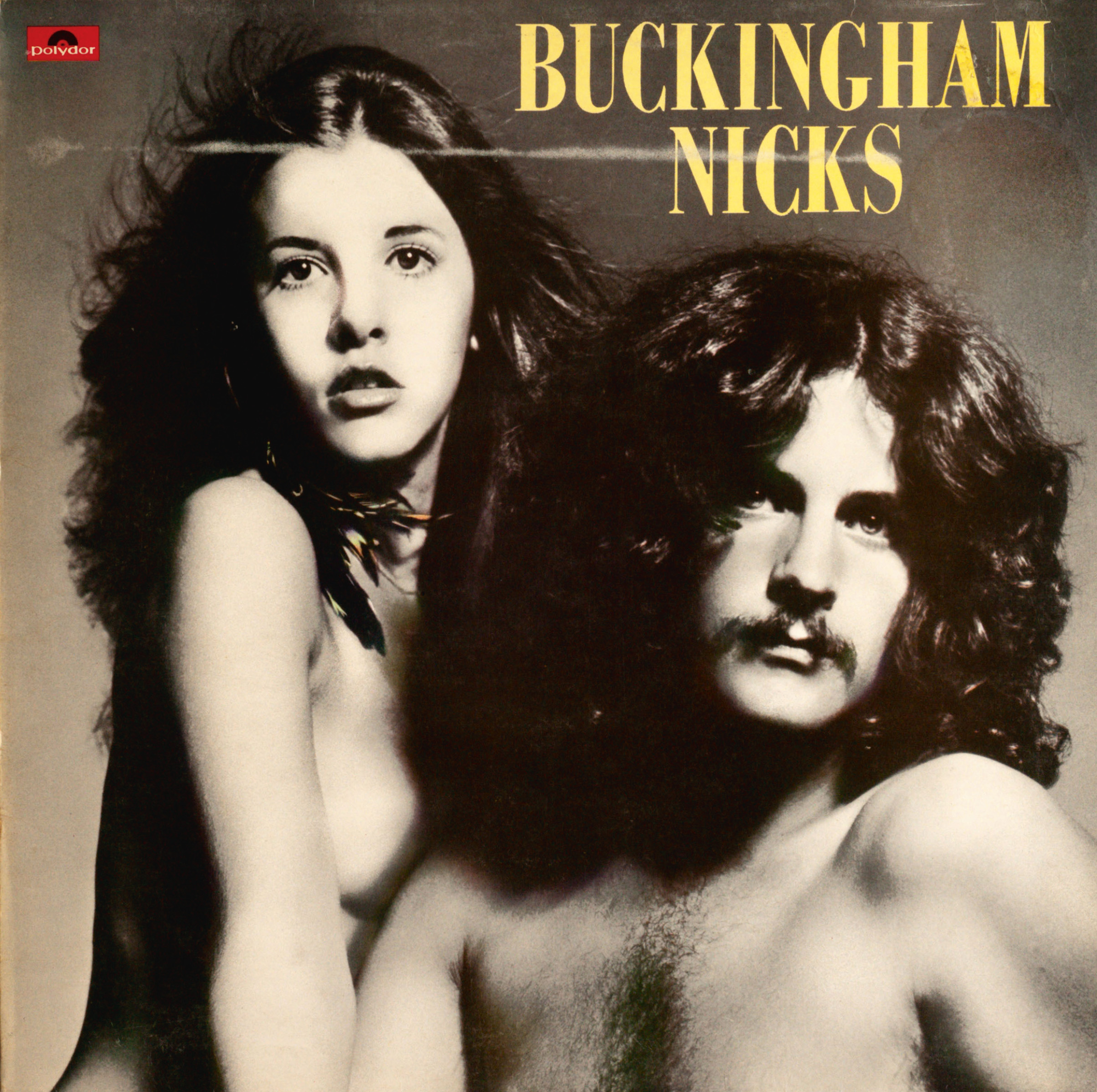

At Olsen’s urging, the Polydor imprint Anthem offered the duo a deal and Buckingham Nicks was released in summer 1973. According to Buckingham, its elegant folk-rock sound was inspired by “Cat Stevens and Jimmy Page’s acoustic guitar playing in Led Zeppelin”. The only place they found an audience was Birmingham, Alabama, where they’d attract 2,000 paying customers. Buckingham: “In LA, we played to 20 people.” Without label support, the album died.

Undeterred, Buckingham carried on writing songs. He and Nicks had now moved into an apartment with Sound City’s assistant engineer, Richard Dashut. Nicks took a job waitressing for $1.50 an hour at a Hollywood restaurant, while Dashut and Buckingham worked on the music. Nicks: “I’d get home at 6pm, fix dinner and straighten up, ’cos they’d been smoking dope and working on songs. Then from nine until three, I joined Lindsey on the music. Then I went to bed, got up and went back to my waitressing job.”

WHILE BUCKINGHAM NICKS TOILED under the radar, compiling the bulk of a second album, Anthem went bust, and when Nicks went home to visit her family, they were shocked by how much weight she’d lost. For her, the offer to join Fleetwood Mac couldn’t have come at a better time.

“After Keith came to see us on New Year’s Eve, I scraped together every dime I could find, went to Tower Records and bought all the Fleetwood Mac records. And I listened to them. Lindsey did not. He listened to the songs that had been hits in England. I told Lindsey we could add a lot to this band.”

“I wouldn’t say that I had to be persuaded to consider joining Fleetwood Mac,” insists Buckingham. “But there was some ambivalence. We were working on our second record, and much as I’d been a fan of Peter Green I wasn’t sure what this band was now. They’d gone from incarnation to incarnation…”

Nevertheless, the pair agreed to meet the band for dinner. “I said, Listen Lindsey, we’re starving to death here,” laughs Nicks. “If we don’t like them, we can always leave.”

“I went to Tower Records and bought all the Fleetwood Mac records I could find. I thought we could add a lot to this band. I said to Lindsey, We’re starving to death here. If we don’t like them we can always leave.”

Stevie Nicks

In the meantime, Fleetwood had played the Buckingham Nicks LP to the McVies. They liked what they heard, but there was one caveat: “Christine had to meet Stevie first,” says Fleetwood, “because there would have been nothing worse than two women in a band cat-fighting.”

With soundings positive, an ensemble summit was planned at a Mexican restaurant. “Fleetwood Mac pulled up in these two old white Cadillacs,” says Nicks. “Mick was dressed beautifully with a fob watch in his vest pocket. John was so handsome. We went to dinner and we just had the best time. I kept thinking, Oh my God, I can be in this band.”

“As soon as we started rehearsing,” remembers Buckingham, “we found this tremendous chemistry between five people who, on paper, wouldn’t necessarily have been in a band together. But Stevie and I didn’t realise how much was at stake. The others, of course, were trying to keep Fleetwood Mac from going under.”

WORK ON THE FIRST ALBUM BY THE new-build Mac began at Sound City in February 1975, with Keith Olsen producing. “Lindsey and I were a little bit on the rocks when we joined,” says Nicks. “But making the album pulled us together. We healed the wounds in our relationship, because things were going way too well to consider a break-up.”

They brought with them a batch of their own songs. “I didn’t want someone that was going to mimic what we’d done before,” says Fleetwood. “That would have been hokey. Lindsey and Stevie came to us fully formed. It worked right from the start. Chris, Lindsey and Stevie’s voices created these wonderful harmonies. We’d started to explore harmonies with Bob Welch. But we were still unknowing. Lindsey had so much energy. We needed someone with a vision.”

Buckingham admits that in pursuit of said vision he stepped on some toes, notably John McVie’s. “I think there were times when John was railing against something that was good for Fleetwood Mac but not good for his ego,” he says. “But sometimes I could go too far. I’ve always been the troublemaker in Fleetwood Mac.”

Of the album’s 11 songs, Monday Morning, Landslide and Rhiannon had been written for the notional second Buckingham Nicks album, while a version of Crystal had appeared on the duo’s debut LP. “I remember John coming up to me in the studio and saying, ‘We used to be a blues band,’” says Keith Olsen. “And I said to him, But John, this is a much shorter road to the bank.”

Fleetwood Mac’s 10th album, titled simply Fleetwood Mac, was released in July. At first, radio support was slow. But the band went straight out on tour to show off the new line-up. In the studio, Buckingham was the band’s driving force. Live, Nicks became its focal point. Dressed in top hat and black chiffon, she lived out Rhiannon, her signature song about a Welsh witch, bringing a touch of glamour and theatre to the band.

“There were no ruffled feathers with Christine,” insists Fleetwood. “Chris hated having to go out front and sing. She was happy for Stevie to do it. And having Stevie and Lindsey in the band also encouraged her songwriting. Chris came into her own as a writer.”

In September, Warners released Christine’s Over My Head as a single. It was the push Fleetwood Mac needed. The single broke into the US Top 10. A month and a half later, the album had sold a million copies. “Only me and John knew what it felt like,” says Fleetwood, “because we had been there when the band were huge in England. For the rest of the gang it was a case of, ‘Oh my God! What is this?’ For John and I it was more emotional. After living through the Peter Green era, we realised that something special was happening again.”

YET, IN TRADITIONAL FLEETWOOD Mac style, they would soon be brought back to earth. Seven years of living, recording and touring together had taken its toll on the McVies. Christine announced that she was leaving John, and was now seeing the group’s lighting director, the improbably named Curry Grant. Neither party considered leaving Fleetwood Mac, though. “We had two alternatives – see the band collapse or grit our teeth and carry on,” recalled Christine.

Not wishing to lose momentum, the group came straight off the road and began planning their next album. By February ’76, they were at the Record Plant in Sausalito. The ramshackle-looking studio on the San Francisco Bay inside resembled a padded cocoon: dark, claustrophobic. One room in the facility had its own bed surrounded by velvet drapes with a control booth sunk into the floor. It was nicknamed Sly Stone’s Pit, as Stone had spent most of his time in there while making There’s A Riot Goin’ On.

The band hired two co-producers: Buckingham and Nicks’ former flatmate Richard Dashut, and Ken Caillat, who’d just helped engineer Warren Zevon’s debut. Fleetwood handed them each a Chinese I-Ching coin to generate some “good-luck energy”. They’d need it.

Somewhat naively, Fleetwood had rented a house for the band to live in just behind the studio. Nicks: “Chris and I managed one night there, and then said, No way. We left the boys to it and rented a place of our own.” Nicks had her own reasons for moving: she had just told Buckingham that it was all over between them. “Lindsey and I were fast, rich, beautiful and successful,” she says. “And,” quips Buckingham, “there is nothing like success to undermine… things.

“Stoking the tensions, Fleetwood insisted the band work 12-hour days.”

“Stevie and I had been having problems,” he continues. “But when Chris left John you had this situation where the two women reinforced each other’s notions… It was a catalyst to speed up what would have happened to Stevie and I anyway, but might have taken longer under normal circumstances.”

The studio atmosphere was understandably charged. “I thought I was going to be making a regular album,” says Ken Caillat. “Then I heard this yelling and saw Chris throw a glass of champagne in John’s face. Then Stevie and Lindsey started having an argument over the microphone. Then Mick walked in with tears in his eyes as he’d just got off the phone to his wife. I started to think it was contagious.”

Stoking the tensions, Fleetwood insisted the band work 12-hour days. “If we finished at midnight, I tried to make sure we didn’t start the next day until noon,” says Caillat. “But Mick was obsessed. We worked 35 days straight without a day off.”

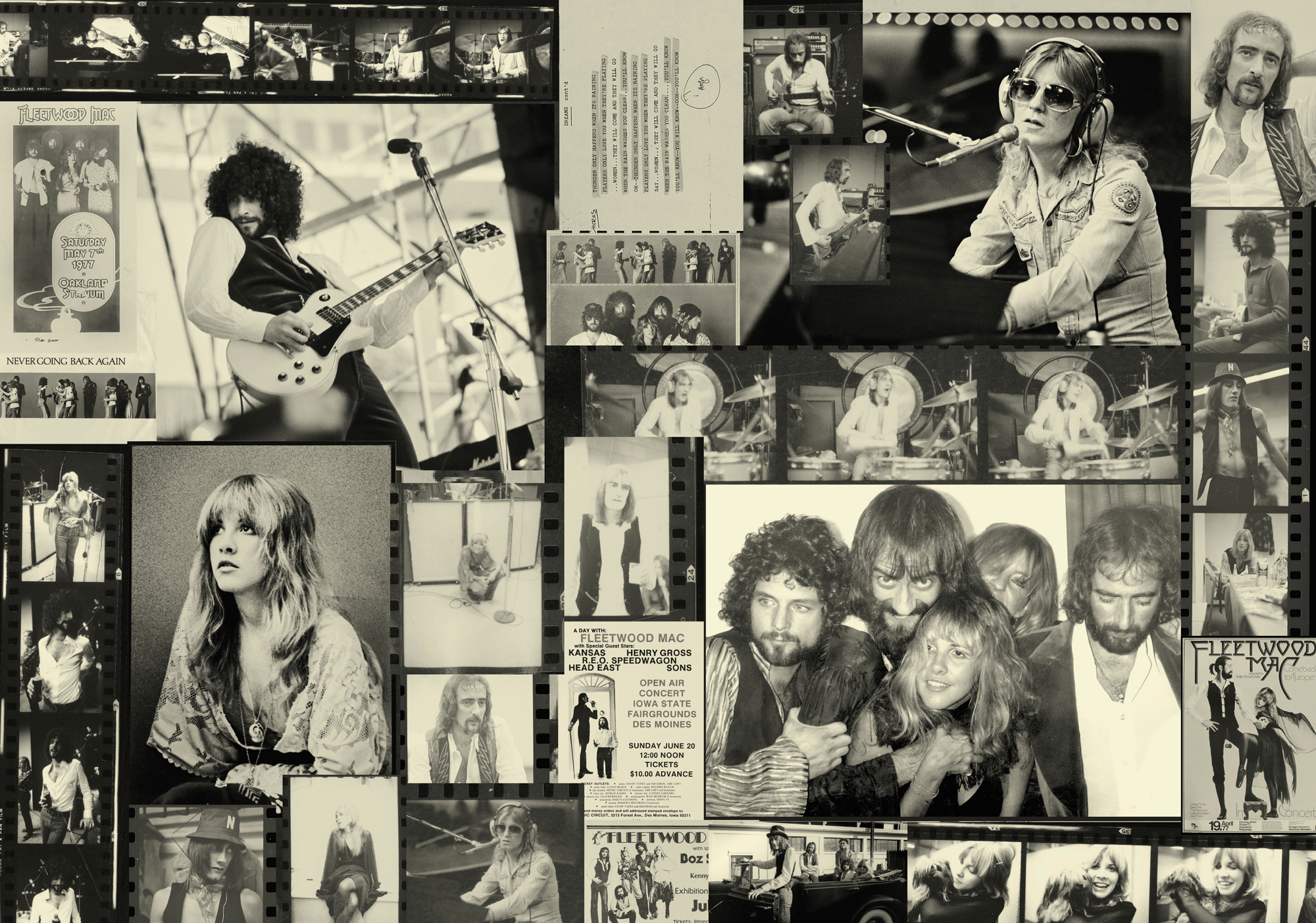

World turning: Fleetwood Mac on-stage with one of Mick Fleetwood’s children, Oakland Coliseum, April 25, 1976.

STORIES FROM THE MAKING OF Rumours have since entered rock’n’roll folklore. But Caillat insists that, despite one report, Fleetwood never removed the studio clocks to prevent the band from knowing how long they’d been working. “It was so dark in there, you never knew whether it was day or night anyway.”

Reports, too, that they spent four days tuning a piano have been exaggerated slightly. “Yes, it did drag on for four days,” Buckingham says, “but we weren’t tuning for 12 hours a day. We were trying different tuners. Though it’s quite conceivable that in those days when everyone was a little… er, wacked out, it took longer than it should have done.”

Coming off the back of a platinum album, the band indulged themselves. An electric harpsichord was shipped in for Stevie’s spooked-sounding ballad Gold Dust Woman. To achieve a certain rhythmic effect on Lindsey’s percussive Second Hand News, Buckingham ‘played’ the faux-leather seat of a studio chair. Fleetwood, meanwhile, recalls hours wasted looking for some elusive sound effect by lashing two bass drums together. “I used to sit there and read, crochet or draw while all this was going on,” says Nicks. “And I would make my little suggestions, like a wingman.”

However, getting “wacked out” was also becoming an occupational hazard. One night was lost after the band consumed a tray of cookies, not knowing they were laced with marijuana. Nicks: “We sat there for hours just staring at each other.”

There was also a communal bag of cocaine on the mixing desk.

“Rumours was the beginning of their cocaine use,” states Caillat. “At that time, they were amateurs. This bag sat there for anyone to help themselves. But of course that meant there were times when we worked till 4am and then had to take the next day off.”

Along with the workload, the cocaine helped blot out the trauma in their private lives. “You felt so bad about what was happening that you did a line to cheer yourself up,” sighs Nicks. “We honestly thought that it couldn’t harm us. That it wasn’t addictive. How wrong we were.” Later, Fleetwood informed journalists that Rumours would have carried a credit for his coke dealer – had the dealer not been murdered before the record came out.

“I thought I was going to be making a regular album. Then I heard this yelling and saw Chris throw a glass of water in John’s face. Then Stevie and Lindsey started having an argument over the microphone.”

Ken Caillat

“When it comes to these war stories about our substance abuse, I am the prime candidate,” Fleetwood concedes. “I was very open about my cocaine use. These days I try to de-romanticise all that. But it’s true. It happened. I always imagine us making Rumours was a bit like Paris in the 1920s.”

Fleetwood’s enthusiasms were infectious. “My attitude was ‘when in Rome…’” says Buckingham. “But I was never the guy buying the stuff. On Rumours, I don’t think I went for more than 36 hours straight without sleep. Though I can’t speak for the rest of the band and certainly not Mick.”

Their noses may have been numb, but their songs – heartbroken, tumultuous, addressing specifics about their writers’ lives – were anything but. “Dreams and Go Your Own Way are what I call the ‘twin songs’,” says Nicks. “They’re the same song written by two different people about the same relationship.”

Nicks remembers Dreams unfolding in Sly Stone’s velvet-draped pit. With just a cassette player and Fender Rhodes piano for company, she conjured a gentle elegy for her and Buckingham’s relationship. By contrast, Buckingham’s Go Your Own Way was an angry kiss-off.

“Lindsey took a more punk rock approach,” shrugs Nicks. “But that was his way of getting through it. I still don’t like the line in Go Your Own Way – ‘shacking up is all you wanna do’ – but unfortunately that’s how he felt about me. And I have to live with that.”

“I guess Stevie would rather have seen that song politicised,” Buckingham ripostes. “But what are you going to do? There is so much truth going on in all of those songs that there is no way you change them.”

“They were writing those songs about and to each other,” observes Mick Fleetwood, “and then singing them on the same mike. I don’t know how they did it. Warners were terrified. I had executives phoning up and asking, ‘Do we still have a band, Mick?’ And I said, Yes, because we will not stop what we are doing for anything – even if we have to crucify ourselves.”

“I still don’t like the line in Go Your Own Way – ‘shacking up is all you wanna do’ – but unfortunately that’s how he felt about me.”

Stevie Nicks

TOWARDS THE END OF THE GROUP’S time at the Record Plant, Fleetwood started to believe “that we were all going insane”. The claustrophobic environment was too much: ex-couples were screaming at each other or not speaking at all; the days were blurring into nights; one studio engineer had taken to sleeping under the mixing desk as “it was the safest place to be”. Drugs and alcohol were rife.

A single incident convinced the drummer it was time to move on. “One night I turned up and I saw John McVie, on his own, trying to master a bass part. This very well-grounded Scotsman was on his hands and knees praying, with a picture of his guru and a bottle of brandy in front of him.” Fleetwood pauses, as if he still can’t believe what he saw. “And John was so not that sort of guy. I knew then that we had to get out of there.”

The band emerged from the Record Plant, blinking into the daylight, and headed off on another tour. In between shows, they returned to Los Angeles to finish the album. Fleetwood fielded more calls from concerned executives who now realised the band wouldn’t make the planned September release date. Rumours still wasn’t finished. They had 3,000 hours of recordings, and the master tape was now dangerously thin. During one meticulous 16-hour session, the overdubs were transferred from the deteriorating master to another first-generation tape containing the basic tracks. Caillat: “If we hadn’t done that we’d have lost everything.”

“I think we’d rented every studio in LA,” recalls Nicks. “And just spent months overdubbing and spending more money. We became self-indulgent, spoiled and excessive, but we didn’t care. That was when the cocaine really came into the picture and in a very big way.”

WARNERS ANNOUNCED IN THE final weeks of 1976 that Fleetwood Mac’s new album was imminent. Its working title, Yesterday’s Gone (from a lyric in Don’t Stop) had been changed, at John McVie’s suggestion, to Rumours. Only one song, The Chain, was credited to all five members. The lyric – “I can still hear you saying you would never break the chain” – described what Fleetwood calls “the realisation that the music we were making together was more powerful than any of us.” The song had started life at the Record Plant, then in LA the group re-wrote the verses, and added a new intro, a re-working of the opening to Lola (My Love), a song from Buckingham Nicks

Released in January ’77, Rumours would have the largest advance orders of any album in Warner Bros’ history. By March it had topped the charts in the US, Canada, Australia and the UK: a sweet victory for the three exiled Brits who’d seen Fleetwood Mac written off for dead at home. Four singles from the album would also become US Top 10 hits. At the last official count, Rumours has around 40 million copies worldwide.

Rumours casts a long shadow, one that a further five US Top 20 Fleetwood Mac albums have not shaken off. You sense this is a source of frustration to Buckingham, who quit the band for a time, and has made a raft of idiosyncratic, undervalued solo albums. “I actually think Fleetwood Mac is a better-recorded album than Rumours,” he ventures. “But we always knew Rumours was good, and expected a certain outcome. I don’t think anyone could have predicted the Michael Jackson world we’d find ourselves in.”

Asked what he would do if he heard a song from Rumours on the radio now, he says, “My kneejerk reaction would be to change the station… God! Why is that? I guess it’s because it might dredge up the subtext around the songs, and that’s not always pleasant.”

“Oh, Lindsey, what’s the matter with you?” laughs Nicks, when MOJO informs her of her ex-partner’s response. “I can be walking down the street and hear something, and think, What’s that? And a block or two later I realise I am hearing Mick’s drums and John’s bass, and it’s a Fleetwood Mac song playing. I can actually feel it in the ground. And it always makes me smile.”

Christine McVie will not be joining Fleetwood Mac’s 2013 tour. She quit in 1998, and since a solo album, In The Meantime, in 2004, has retired from the public eye. “Christine sold her house in LA, got divorced, went back to England, burned every bridge she had,” says Buckingham with unexpected vehemence. Nicks says she misses her: “If I could talk Christine into coming back, I’d be on a plane to England tomorrow.”

“Rumours was the beginning of their cocaine use. At that time, they were amateurs. This big bag sat there on the mixing desk for anyone to help themselves. Sometimes we worked until four in the morning then had to take the next day off.”

Ken Caillat

So fans will see just the one bittersweet love affair relived on stage, though its two parts lead very different lives these days. “Lindsey has two daughters now, and lives in girl world,” laughs Nicks. “That’s been good for him. It’s softened him up. I am single by choice. I took the choice of following my music. I could not have done that if I was married and certainly not if I had a child.”

At any Fleetwood Mac show, the loudest applause greets the songs from Rumours, and the moment when Buckingham takes his ex-lover’s hand. It’s showbiz, but you sense emotions still simmering. “Touring with an ex is not a problem,” he says, “but I think there are still parts of mine and Stevie’s relationship that are unresolved, and it will be interesting to visit that on this next tour. I know that what makes Rumours so attractive to people is the fact that we were making this music while all our hearts were breaking.”

“Fleetwood Mac were practically finished in 1974,” says Mick. “I drove past that supermarket in Laurel Canyon a while ago. And I thought to myself, What on earth would have happened to me, to all of us, if I hadn’t stopped there that day?”

IMAGES: GETTY/ALAMY