Mojo

FEATURE

DOUBLE TROUBLE

A double-album seemingly designed to sabotage their career, Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk was a multi-million-dollar hymn to excess, made by a band in the midst of emotional and chemical breakdown. In September 2003, MOJO met up with the group in New York to journey back to Tusk’s extraordinary creation in the late ’70s, a time of musical and personal uncertainty, vast amounts of booze and drugs, and very confusing intra-band relationships. And that’s before the year-long world tour to promote it…

Words: Phil Sutcliffe

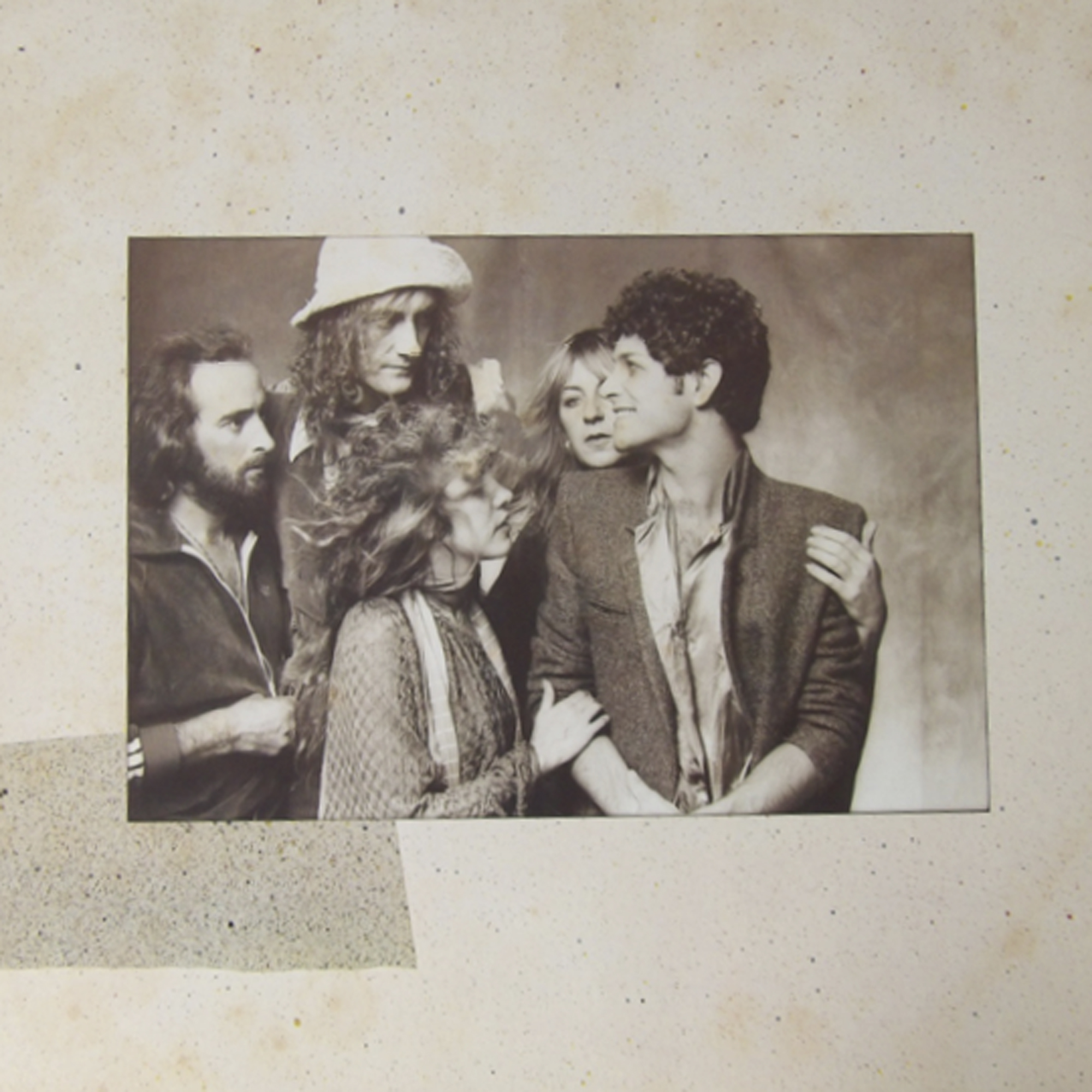

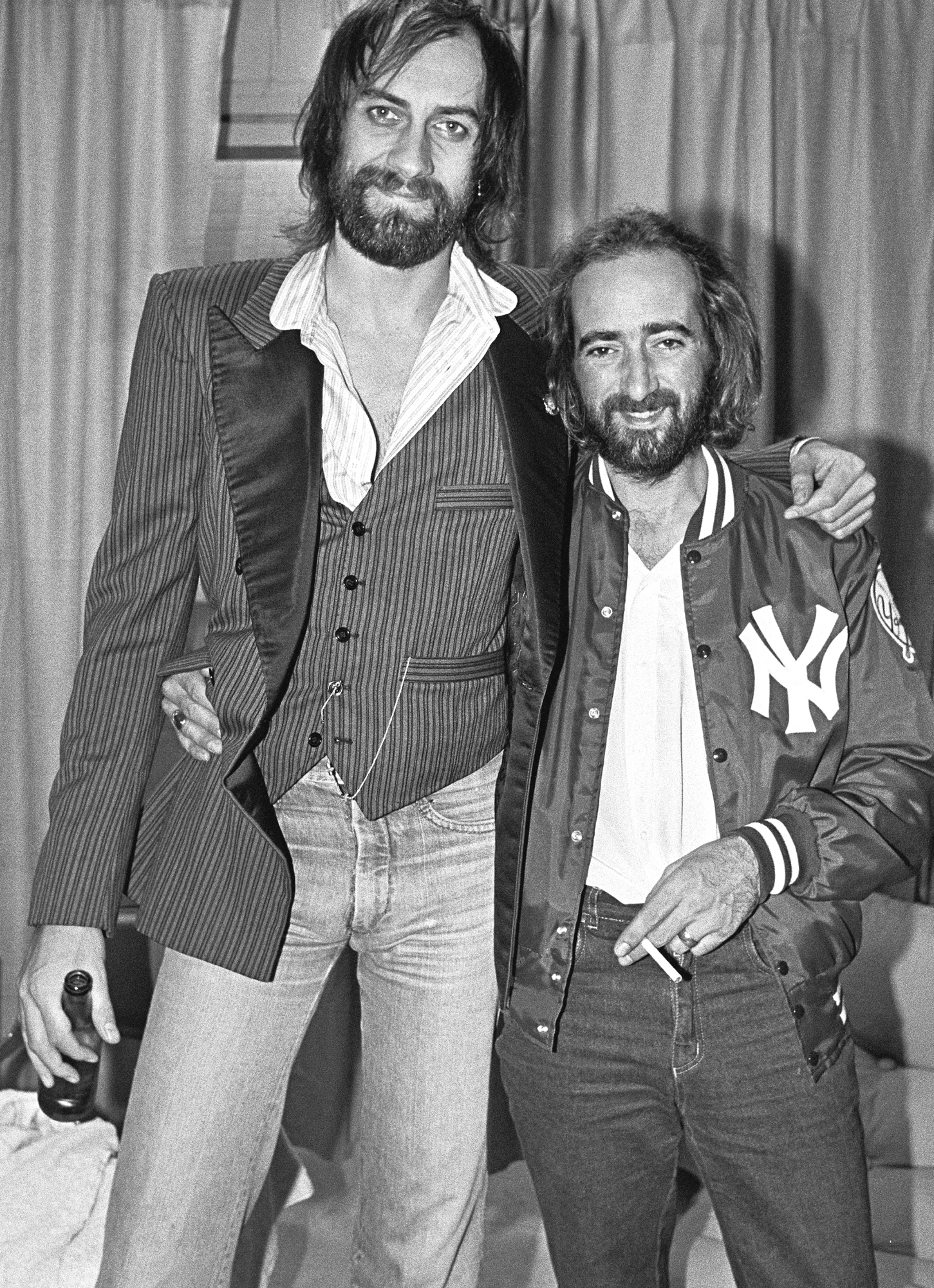

“GOD KNOWS ALL OUR lives are unimaginable without each other,” mutters Mick Fleetwood, glancing speculatively from one old friend to another. It’s quite a thing to say at Madison Square Garden in front of 20,000 people when you’re really just introducing the band. This is Fleetwood Mac, though, the longest-running soap opera in rock’n’roll, so portentous lines never go amiss.

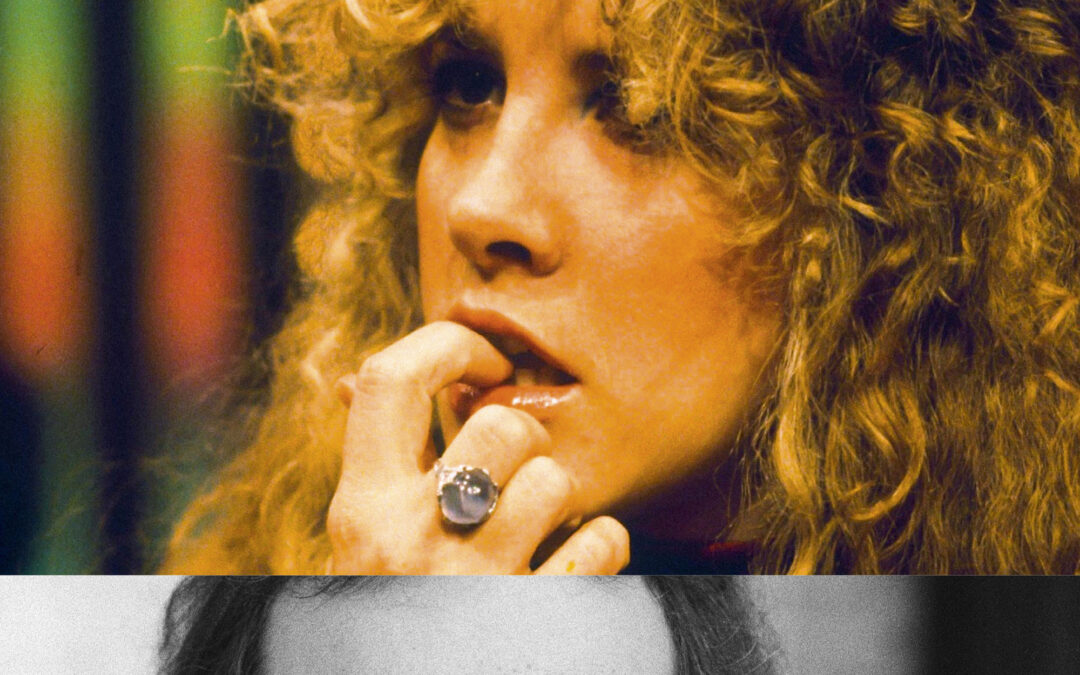

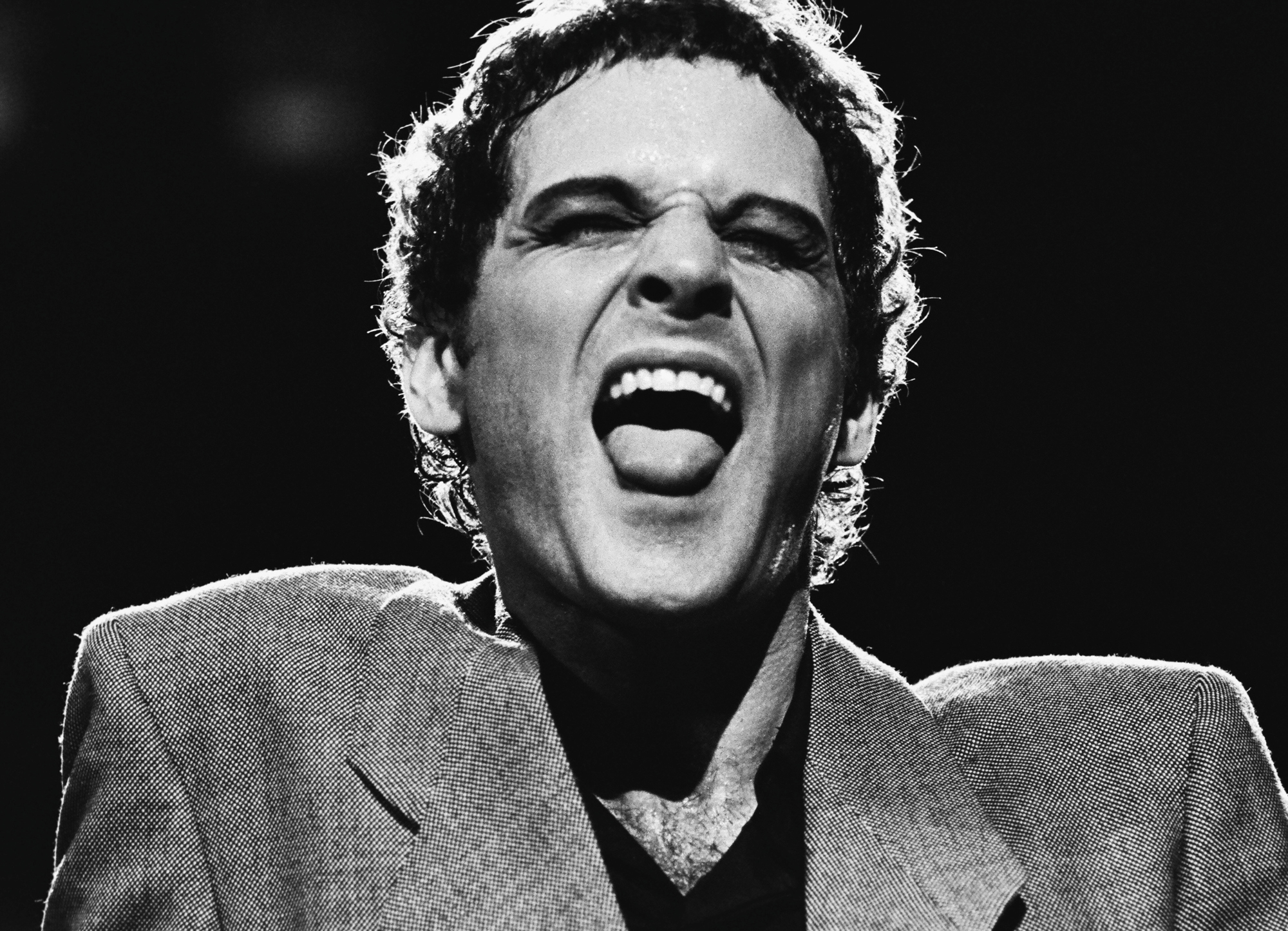

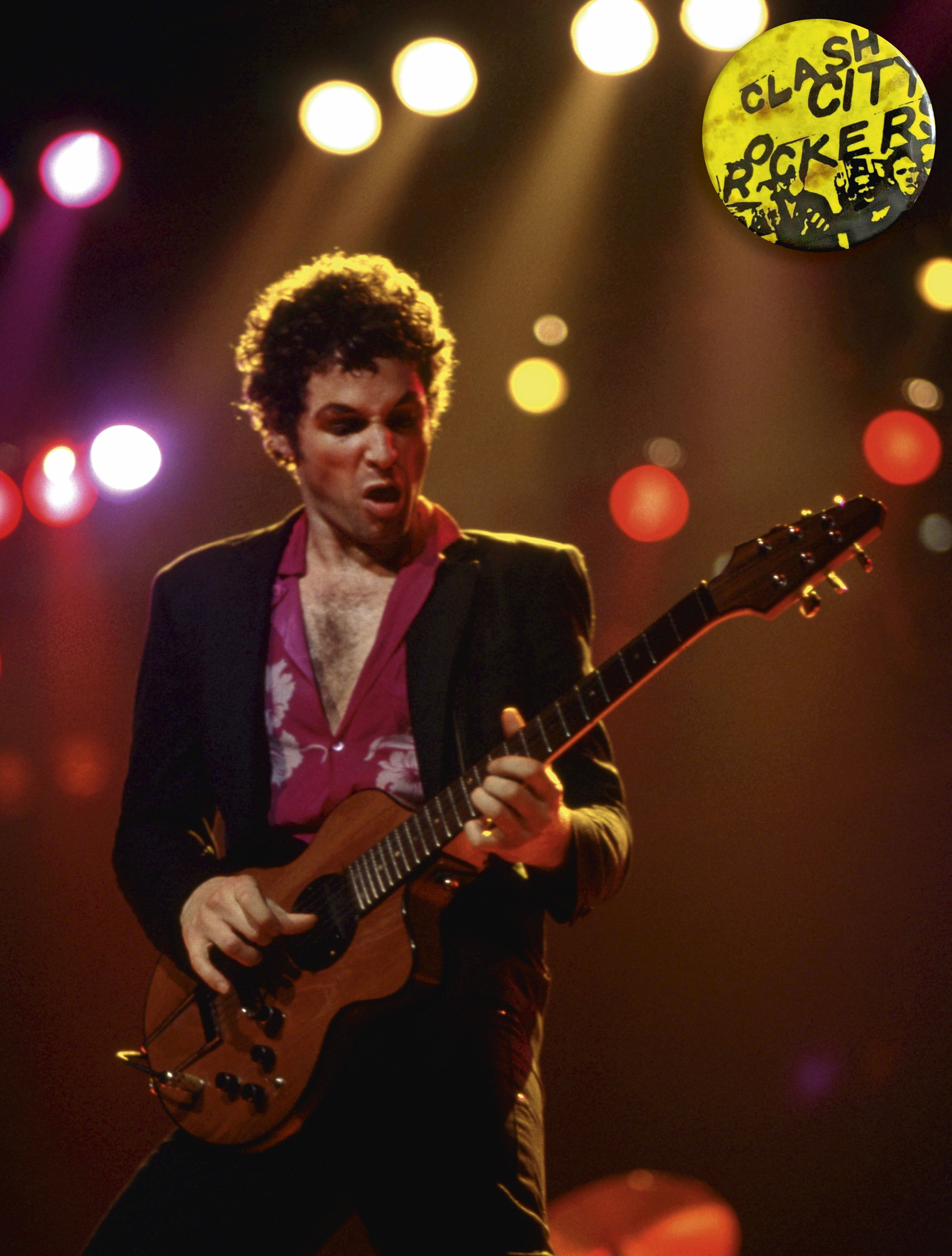

Trim Lindsey Buckingham, 55 this year, sings like a deranged Roy Orbison, dazzle-fingers the guitar strings, then stumbles away thumping his heart as if each solo might be his last. Stevie Nicks, 55 too, aflutter with black lace, so forgets her trademark wafty witchy ways that she punches the air like a goal scorer, defying the logic of middle-age, gravity and her stilettos to kick up her skirts and execute a dizzying Dervish twirl.

Buckingham breaks from the clinch and, bent like Quasimodo, makes for a microphone. He tilts his head back and roars, “Rrrrrraaaaaarrrrr!”

“Me and Mick weren’t talking to each other much. We were there but looking past each other. Everyone was nervous: ‘Is she going to burst into tears and leave?’”

Stevie Nicks

THE FOLLOWING AFTERNOON in a fabulously wood-panelled suite at the Waldorf Astoria, Stevie Nicks, just like on-stage, a living susurrus in diaphanous black, is chuckling about Buckingham’s silly walk and animal noises. Nothing to do with Victor Hugo, she says: “It’s Tusk the elephant. That whole African-drum, tusk-in-the-air, happy, religious, ritualistic thing, with Mick as the African chief. Making that record, we became like a tribe. In the studio we had two ivory tusks as tall as Mick on either side of the console. The board became ‘Tusk’. If something went wrong it was, ‘Tusk is down.’ Those 13 months working in that room were our journey up the sacred mountain to the sacred African percussion, uh, place, where all the gods of music lived.”

Frankly, sacred mountains and gods of music are just the ticket to start MOJO’s retrospective on the notorious vinyl double that was 1979’s Tusk. Back then, record moguls dubbed it “Lindsey’s folly”. Yet, of late, the album has undergone a reappraisal, with The Guardian recently calling it “a landmark of radical MOR”. How prescient American critic Greil Marcus looks now, having written in his October 1979 Tusk review that “Fleetwood Mac is subverting the music from the inside out, very much like one of John le Carré’s moles, who, planted in the heart of the establishment, does not begin his secret campaign of sabotage and betrayal until everyone has gotten used to him, and takes him for granted.”

TUSK ERUPTED OUT OF lives in a tornado of turmoil. Three years before the abum, with Buckingham Nicks a promising duo and utterly broke, Nicks became a cleaner, setting aside her chiffon in favour of “Ajax and a toilet brush”. Then Mick Fleetwood called and everything went wild. Joining Fleetwood (drums/band manager) and the McVies, John (bass) and Christine (keyboards/vocals), they made a US Top 10 album, Fleetwood Mac, which successfully shifted the band’s reputation from the Brit R&B of the Peter Green days to Californian soft rock. Then came the global monster Rumours. In the course of this vertical take-off, malign scriptwriters seemingly took over their lives.

Christine McVie walked out on her marriage to John, largely because of his boozing, and soon she was living with band lighting engineer Curry Grant. In the early days of Tusk, John married his secretary, Julie Ann Reubens (one relationship that endured). Nicks broke up with Buckingham after five fraught years and took up with the Eagles’ Don Henley and others, while Lindsey played the field before going steady with a woman called Carol Harris. Fleetwood and his wife Jenny Boyd (the model younger sister of Pattie Boyd) divorced and remarried. Then, unbeknownst to the band, the drummer began an affair with Nicks.

And everyone drank, smoked and snorted loads.

Unsurprisingly, then, when Buckingham called at Fleetwood’s Bel Air home early in 1978 to discuss strategy – “What the fuck were we going to do now?” as the drummer puts it – it took three days.

Still sporting an enormous Afro yet captivated by new wave, Buckingham insisted that he couldn’t stand any laurel-flaunting ‘Rumours II’ operation. Sitting in an airily sumptuous apartment at the Ritz-Carlton, he tells MOJO how he tried to convey that, in adapting to the band, “I was losing a great deal of myself” – to both their music and high-on-the-hog lifestyle. He wanted to record his songs at home, then bring them to the band.

Fleetwood, now 56, is ensconced a hundred yards along the block in the rather more antique Plaza (different hotels because they all have their New York favourites; otherwise they’d all stay together, honest). His ultimate reaction to the “new boy” was that “what he suggested was quite possible and, I thought, a survival plan for the band – although I know I understood it more readily than John and Christine did.”

“Begrudging agreement” was all Buckingham needed. That May, he went home and got stuck in.

A daytime person and fervent admirer of the discipline his Olympic silver-medallist older brother Greg brought to swimming, he discovered “an extreme focus which was in many ways to the detriment of other parts of my life, I know. My thought was, let’s subvert the norm. Let’s slow the tape machine down, or speed it up, or put the mic on the bathroom floor and sing and beat on, uh, a Kleenex box! My mind was racing. I loved it.”

Bearing home tapes of squally, manic pieces like The Ledge and Not That Funny, Buckingham would join the band at Village Recorders where the owners had re-equipped Studio D for around $1.4 million. The band were supposed to buy it, but when that deal fell through they ended up paying much the same in rent – not to mention nightly lobster and champagne takeaways.

The shiny-new-machine look didn’t last. Tickled by the tusks, Nicks hung drapes above the desk, stuck paintings and Polaroids on the walls and plugged rainbow lights in everywhere. “It became very vibey, mystical, incensy and perfumed,” she says.

But Buckingham was not for soothing. Engineer Ken Caillat, a Tusk co-producer, still frowns on the guitarist’s contrariness: “He was a maniac. The first day I set the studio up as usual. Then he said, ‘Turn every knob 180 degrees from where it is now and see what happens’. He’d tape microphones to the studio floor and get into a sort of push-up position to sing. Early on, he’d freaked out in the shower and cut off all his hair with nail scissors. He was stressed. And into sound destruction.”

Given the band’s emotional history, calming influences hardly abounded. John McVie – not doing interviews for this piece – found himself regularly advising the whippersnapper Buckingham to get his hands off the bass parts. This was one reason for the bassist’s early departure from the studio to his ocean-going yacht and consequent substitution by a cardboard cut-out in the video for the Tusk single.

While Caillat recollects “some kind moments” between Buckingham and Nicks, the guitarist/producer sees the peaceful passages as “exercises in denial”. Tellingly, he has recalled Nicks “coming in once a week to do her song and that would be it”, while the singer’s own perception was that “I was in the studio every day for 13 months”. Feeling insecure within the band, she bonded more than ever with Christine and engaged the Eagles’ manager Irving Azoff, with whom she secretly set up a new label, Modern, to launch a solo career.

She didn’t inform Mick Fleetwood of this intention until January 1980. Their own veiled affair, meanwhile, continued beyond the collapse of Fleetwood’s remarriage to Jenny in 1978, only to end suddenly that October when he fell for Sara Recor, Nicks’ best friend and titular inspiration for the song, written a few months earlier, that became Tusk’s most enduring hit.

“Buckingham collapsed in a Philadelphia hotel suite with a seizure, soon diagnosed as epilepsy. Intimations of mortality?”

For months after that, says Nicks, “We weren’t talking to each other very much. We were there, but looking past each other. Everybody was nervous: ‘Is she going to burst into tears and leave?’” Nicks believes the rest of the band realised what was going on, but Buckingham, his attention and perceptions fiercely “compartmentalised”, has said he knew nothing until a couple of years after the event when Fleetwood, in English gentlemanly fashion, gave him a ‘There’s something you ought to know’ speech.

Nor was that the last of the complications. Nicks had a liaison with Caillat’s assistant engineer, Hernan Rojas. Christine McVie met Beach Boy Dennis Wilson one night at Village Recorders and within days he had moved into her mansion, haunting the Tusk sessions thereafter – Caillat describes him “coming in hammered, stinking of alcohol, walking around with a jug of vodka and orange juice in his hand”.

The uproar wasn’t all about love, though. Tusk’s leading actors, In July 1978, during a tour between recording sessions, Buckingham collapsed in a Philadelphia hotel suite with a seizure, soon diagnosed as epilepsy. Intimations of mortality? “Not really. More, What the hell was that? You’re on the bathroom floor, your girlfriend’s crying and you’re, Huh? What? It does take a horrible toll on your body. You go into this complete coiled-spring thing. But once I was prescribed Dilantin I had no more problems.”

Then, within a few months, his father died, aged 56, after years of heart problems probably caused by the strain of running the family’s troubled coffee business. Morris Buckingham, who always encouraged Lindsey’s rock’n’rolling when a career in law or architecture would have better suited his social standing, is one of Tusk’s co-dedicatees. The other dedicatee is Wing Commander Mike Fleetwood, Mick’s father, who died of cancer in summer 1978.

When Fleetwood learned that his father was fading he flew home. He was able to say a proper farewell and his father’s spirit stayed with him, quite tangibly, while the Tusk maelstrom raged to a conclusion.

“My father and mother used to come on tours with us for weeks on end,” says Fleetwood. “They were like parents to everyone on the road. I’d been hopeless at school and when I was 15 my father backed me in leaving to go to London and play drums. So it was gratifying to know he’d seen my pipedream come true.

“But after he died what I always had with me was the tapes he’d made of his own poems and other writings. Fantastic pieces. Whenever I’d get drunk we’d all sit around listening to my dad! Well, in truth, it was probably a bit strange to some people: ‘Oh, there goes Mick again, playing his dad’s tapes, sitting there on the floor with tears pouring down his cheeks.’ But that’s how much that all meant to me.”

“You’re insane doing a double album at this time. The business is dying a death, we can’t sell records and this will have to retail at twice the normal price. It’s suicide – you’ve got to stop them!”

Warners Boss Mo Ostin

IN JUNE 1979, TUSK was done. Fleetwood Mac had a high old time recording the title track’s brass section and shooting the video at Dodger Stadium, with the 100-strong University of Southern California Trojan Marching Band. Nicks led the baton-twirlers, as she used to in high school, and Fleetwood banged the big bass drum. He updated Warners boss Mo Ostin on what they’d been up to – the 20 tracks, the million dollars – and recalls a response along the lines, “You’re insane doing a double album at this time. The business is fucked, we’re dying a death, we can’t sell records, and this will have to retail at twice the normal price. It’s suicide. You’ve got to stop ’em!”

So they went ahead. They had the power.

On October 12, out came 20 tracks and 75 minutes of strange, tripolar sounds – Buckingham barking and hollering away into the back of beyond, Nicks murmuring mysticism and McVie cooing and coaxing with the cool elegance of classic pop.

The opening two tracks set the tone. McVie’s Over & Over floats on a gentle stream of dappled piano and slide guitar, lovely, simple but neither daft nor innocent as it frets, albeit languidly, “Don’t turn me away / And don’t let me down”. Next up, it’s Buckingham’s The Ledge, and suddenly you’re at some deranged circus, drums stomping like a seaboot dance – Fleetwood’s blissfully minimalist sophistication on Over & Over is the perfect antithesis – the guitar off-key and ungainly, the voice gloating, nagging, slurry and barely comprehensible. Nicks makes her entry with track five, Sara, laid-back cruise-rock and full-on sex, “Drowning in the sea of love / Where everyone would love to drown”.

And so it rolls. The oddball and the familiar. The rowdy and the slick. Arguably, it’s even the man versus the women, as nine Buckingham tracks oppose – complement? – six from McVie and five from Nicks. Even so, while these extremes can hardly be overstated, Buckingham’s recollection is that the band did play on all but one of his songs – Save Me A Place – and his guitar, production and harmony vocal contributions to the McVie and Nicks compositions are clearly as diligent and sensitive as they were on the previous two albums. Ultimately, none of them could resist doing their best for the music, regardless of personal conflicts.

Ken Caillat, irked for the duration because he believed the band should “do something like Rumours, the public want that”, fought his corner when he took the lead on sequencing the album; it was he who largely ensured that “those more disturbing songs were spaced out between Christine’s and Stevie’s”. No wonder Buckingham long ago reconciled himself to the view that the Tusk effect is much like a wacky solo album constantly bobbing up and down demanding attention throughout somebody else’s record. But, disjointed and dislocated as it is, there’s not a dull track on it. It’s beautiful and nuts and not at all what’s supposed to happen in the music industry, and that’s why fans and bands are still coming to it fresh.

Yet, cruelly, Ostin’s hard-headed assessment of the times and the economy proved accurate. And the promotional strategists certainly didn’t help matters with a couple of desperate misfires. The utterly eccentric Tusk was the first single released – like some bizarre health warning to Rumours purchasers – after which, with great fanfare, the whole album was broadcast on Westwood One radio to the accompaniment, as Fleetwood later lamented, of a nation’s cassette recorders hissing away. It soon became evident that sales would total less than a quarter of its predecessor’s phenomenal figures.

However, before the recriminations began, the mayor of Los Angeles declared the release date ‘Fleetwood Mac Day’. At the launch party, Nicks took the mic to thank revellers at Frederick’s Of Hollywood’s lingerie emporium for “believing in the crystal vision”.

THE TUSK TOUR PROVED more blur than crystal vision. “It almost killed the band”, wrote Fleetwood in his autobiography. He meant both financially and, at times, physically, as the frazzled fivesome decided that the only way to keep the show on the road from Pocatello, Idaho on October 26, 1979 to Los Angeles on September 1, 1980, was to indulge themselves.

In America, they chartered their own planes, latterly the Caesar’s Palace casino’s private Boeing 707. In Europe, wary of the diligence of airport drug enforcement officials, they hired their own luxurious train.

Hoteliers must have cringed to hear of their coming. First there was the women’s avid gentility. Nicks’ rooms reportedly had to be repainted pink (though the band deny this), so a white piano was required. And Caillat recalls one European stop-over where a window frame was removed and a crane deployed to get a baby grand into Christine’s suite. After the pernickety-ness came the rock’n’roll. Aside from smoke bombs and televisual defenestrations, the men enjoyed a practical joke. A favourite was the celebration of tour manager John Courage’s birthday by filling his room with 50 chickens accompanied, for farmyard verisimilitude, by bales of straw – a feat that must have demanded much effort and expense in San Francisco.

Inevitably, a further king’s ransom was spent on keeping the party supplied with cocaine and alcohol. They even argued extravagantly: Fleetwood has recalled spending $2,000 on an all-night shouting match with Sara on the phone from Japan to California.

Under all this self-inflicted pressure, Fleetwood’s robust constitution began to crack up – conspicuously so before Christmas 1979 at a San Francisco press conference. His whole body went into spasm, though he stayed at his post, trying to answer questions while Christine massaged his shoulders.

“It was hypoglycaemia,” says Fleetwood. “I was manic-depressive, I’d hyperventilate. Eat a bowl of ice cream and I was all right for 20 minutes, then down again. It was 18 months of hell. I thought I was going crazy. I had these weird psychedelic, coma-like visions and quite a few of them turned out to be true. Once, I saw [co-producer] Richard Dashut in the control booth smoking a joint and a policeman walked in behind him. I rang him about it and he said a policeman friend of his had come by the studio that night.”

Eventually, the condition was diagnosed and a diet suggested which, he discovered via rigorous testing, kept the hallucinations at bay while enabling him to “keep on rocking like a madman”.

Buckingham too started to come unscrewed, overwhelmed by frustrations about his relationship with Nicks, the way it ended and her obvious position as crowd favourite at concerts. In March 1980, playing to 60,000 in Auckland, New Zealand while loaded with whiskey (according to Fleetwood), Buckingham pulled his jacket over his head in grotesque imitation of Nicks’ drapes and started to ape her twirling moves. Then he ran across the stage and kicked her. Nicks carried on like a trouper.

In the dressing room afterwards, head hung in shame, he was confronted by Christine McVie who slapped him, threw a glass of wine over him and gritted, “Don’t you ever do that to this band again! Ever! Is that clear?”

For Buckingham, the saving grace of these events is that he can’t remember them. All he can say, with evident bemusement at the person he sometimes was: “Oh, I wouldn’t doubt that I mimicked Stevie on-stage. And kicked her? That could have happened too.”

The end of the Tusk tour came as a relief to everyone. But within weeks, the band members’ accountants and, particularly, Nicks’ man Irving Azoff, had all come to one conclusion about the tour: it played to enormous sell-out crowds and made no money. In two meetings that September, the second at Fleetwood’s house in Bel Air, the player-manager found himself encircled by inquisitorial suits and silent bandmates.

“It was a terrible occasion,” sighs Fleetwood. “My only defence was, Well, you try and stop them spending! Me and John Courage had tried early in the tour. We booked cheaper hotels. But we had so many complaints from the band. We were all basically insane! Instead of five limos we would have 14 because we loved everyone we were travelling with so the lighting guy and so on had cars too.” (Shrewd McVie eventually decided to take his “limo” in cash and travel on the crew bus.)

The band assured Fleetwood they trusted him, they knew he didn’t have his hand in the till. It was just that, as Buckingham puts it, “Mick isn’t a budget kind of a guy.” And that meant, after six years as manager, he had to go – to be replaced by the “committee” of individual representatives who, Fleetwood feels, have complicated band life ever since.

“It was pretty… ugly,” the drummer says. “But I took it like a man. I remember halfway through the meeting I went up to my bedroom for a brandy and I said to Sara I was actually sort of relieved. It was all too much. It hurt. But I understood. And I was sound enough, yet again, to say, I can eat crow and move on.”

TWENTY-THREE YEARS ON, in Madison Square Garden, at the end of Don’t Stop, Buckingham and Nicks strike a startling tableau centre-stage. In profile, she stands with her back to him gazing upwards, he bends low over his guitar, his face buried in her ash-blonde hair. The crowd sighs. And steams. The hands of lovers young and old entwine. But it probably wouldn’t work if it wasn’t based on a true story.

At the Ritz-Carlton earlier that day, Buckingham mused, in his Californian way: “Stevie and I could never quite find each other after Tusk. You have to understand that this is someone I met when I was 16. I was completely devastated when she took off. And yet, trying to rise above that professionally, I produced hits for her. I had to do a lot of things for her that I really didn’t want to do. If I kicked her on-stage, that was… something coming through the veneer. There has been a lot of darkness, a ton of misunderstanding.”

After Tusk, despite catching the blame for its “failure”, Buckingham made two more albums with Fleetwood Mac, quitting in 1988 before the Tango In The Night tour. He released three intense, uncommercial solo LPs, had one rejected by Warners, and drifted back into the Fleetwood Mac ambit via 1997’s The Dance reunion live album. Meanwhile, in the late ’90s, he married and had two children.

Nicks started her solo side-venture with the smash Bella Donna in 1981 and followed it with six others. With her off-stage life dominated by medical problems, she left the band after 1990’s undistinguished Behind The Mask. For eight years she was hooked on Klonopin, a tranquillizer prescribed by her doctor, but since 1994 she has beaten her addictions.

Reconciliation came – slowly – out of the band reunions and, probably, a mellowing in Buckingham. Ken Caillat quotes a recent conversation: “He said, ‘I’m a selfish guy.’ Which is true, he’s all about me, me, me. He admitted he had even been angry about having a child to start with. Then one day the kid grabbed his little finger and he just got it. He understood there was another world there.”

And when Nicks rejoined Fleetwood Mac in 2003 for the intriguingly Tusk-like Say You Will, Buckingham found her ready to laugh about “the time you threw that Les Paul at me” and such.

“Now, on the road, we’ve had many really good talks,” he says. “We’ve known each other most of our lives and yet we’re still trying to figure out what’s going on. Obviously, a lot of love as a subtext. But where is that love? How do we get in touch with any of that? For all of us, the decisions we make now are going to determine how we are as people until we die. Stevie and I are trying to look at it… with care.”

He grunts a laugh. “It’s significant that someone can end up, you know… not having killed you!”

“Now I just adore him,” says Nicks, with candour. “He is my love. My first love and my love for all time. But we can’t ever be together. He has a lovely wife, Kristen, who I really like and they are expecting their third child. The way he is with his children just knocks me out. I look at him now and I just go, Oh, Stevie, you made a mistake!”

“IT’S A FOREVER STORY with those two,” grins Fleetwood. “As it is with all of us.” He likes forever stories. It’s his “obsession” that’s kept the band going since Peter Green’s departure in 1970. Even when Christine McVie quit after recording the rather sorry Time in 1995, Fleetwood and John McVie continued as ever, an ace rhythm section in search of a band.

IMAGES: SHUTTERSTOCK/GETTY/ALAMY