Mojo

FEATURE

Let Me Have It All

The passing of Sly Stone in June shone a light on a genre-mashing genius whose peak, multi-hued music preached unity and transcendence. Stone’s world darkened as drugs took over and The Family Stone fell apart, but the fruits of a recent, unlikely renaissance included a candid memoir and some tantalising music. “Sly still had all these amazing creative talents,” discovers Stevie Chick.

Words: Stevie Chick

On a hot, dry morning in June, at his home in Las Vegas, Greg Errico is ruminating on the death of former bandmate Sly Stone a week earlier, at the age of 82. “It’s been challenging,” the drummer sighs. “I knew it was coming. But when it happens, there’s a lot of reflection, a lot of feelings. For me, Sly left the building a long, long time ago, and never came back.”

To many, Sly Stone had been a walking ghost for over 40 years, a funky Icarus who flew too high and was then engulfed by his addictions. After the release of his 1982 album, Ain’t But The One Way, one of the brightest stars of his age wandered into the shadows, to become a creature of rumour and whisper. And while, says author Ben Greenman, who co-wrote Stone’s 2023 memoir Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin), Stone had “no shortage” of opportunities to return to the spotlight, “he could not or did not seize them”.

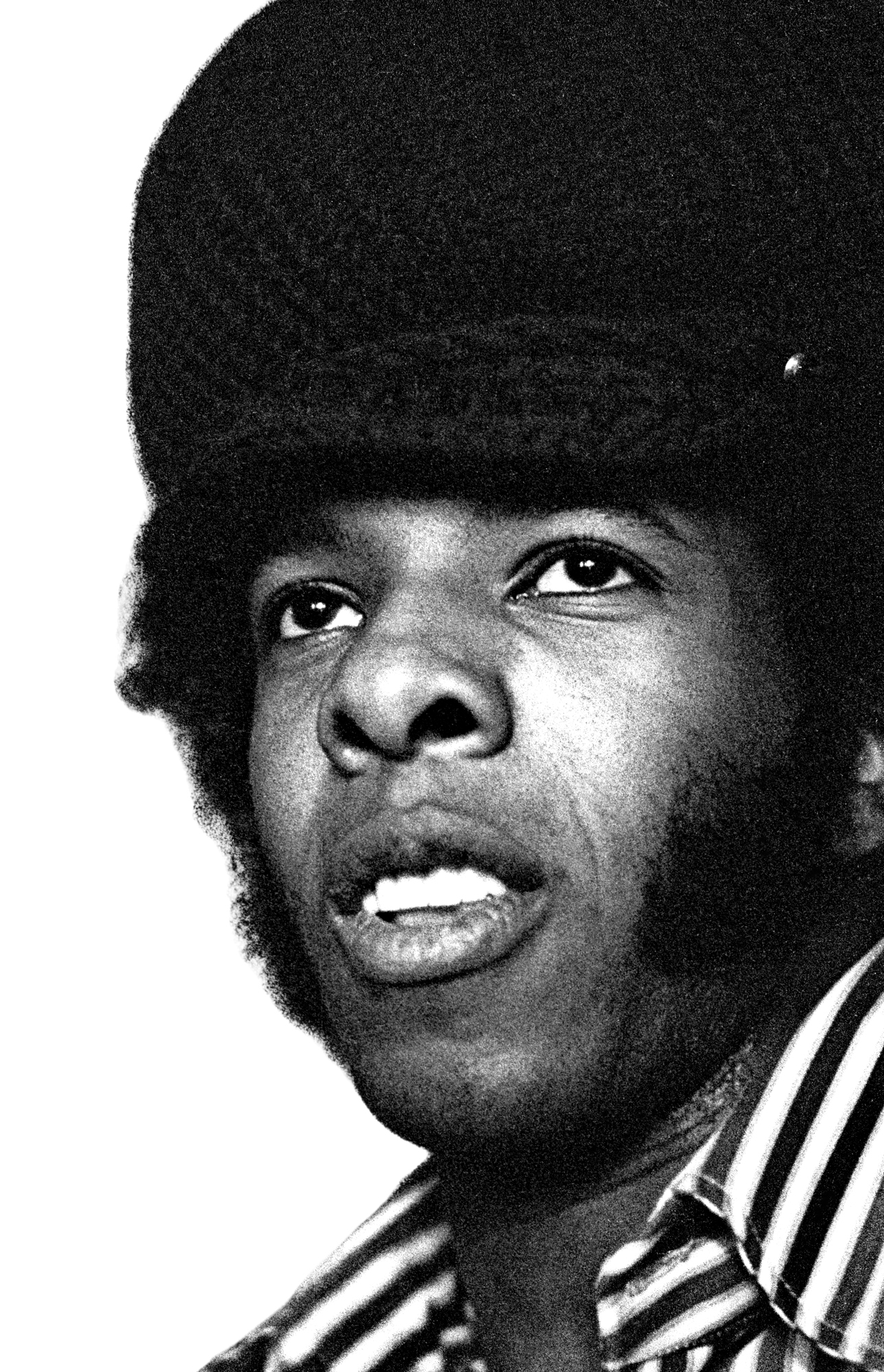

Sylvester Stewart at KSOL, San Francisco, circa 1967

Subsequently, a narrative of disappointment and squandered talent has haunted Stone’s legacy. “Sly is denied the read on his career granted to Jimi, Janis or Jim Morrison, because he didn’t die young,” argues Greenman, who conducted hundreds of interviews with Stone for their book. “Otherwise he’d be remembered for one of the most seamless, god-tier careers in cultural history, akin to the Pablo Picasso of music.”

Stone’s downfall confirmed him a mere mortal, but that initial seven-year burst of success told a different story, of a man for whom nothing seemed impossible. The leader of a group whose interracial, pan-gender line-up issued a joyful challenge to an America still riven by segregation and prejudice; the composer of a chart-topping fusion of soul, rock and psychedelia so revolutionary it made Miles Davis change direction. Stone danced across the stages of the Fillmore, the Woodstock festival and Madison Square Garden like he owned them. For seven or so years, he did.

Those who knew Sly Stone best are now trying to make sense of a life composed of contradictions, of glorious triumphs and tragic burnout, of love’n’hate. “You know how cats have nine lives?” asks Errico. “Sly had nine cats’ worth.”

Sly & The Family Stone, 1967 (from left) Sly Stone, Jerry Martini, Cynthia Robinson, Freddie Stone, Greg Errico, Larry Graham

Born Sylvester Stewart in 1943, Sly Stone had been a star since his teens, a regular on Dick Stewart’s Dance Party, San Francisco’s answer to American Bandstand. There, he met Jerry Martini, saxophonist with Joe Piazza & The Continentals and later Dance Party’s in-house band. Martini backed Stone’s early group The Viscaynes in the show’s talent contests, and a deep friendship developed, Martini regularly stopping at Stone’s folks’ house after his regular gig at America’s first topless bar, The Condor Club. “Sly would bring out his binder full of songs he’d written,” Martini remembers. “There were already over 300 in there.”

A polymath performer with a producer/songwriter side-hustle, Stone produced his first Top 10 hit, Bobby Freeman’s C’mon And Swim (with Martini on sax), in 1964, later helping The Great Society, fronted by future Jefferson Airplane star Grace Slick, record an embryonic Somebody To Love. He was also a disc jockey, with 700,000 listeners in the Bay Area. Martini was inordinately proud of his friend – “Sly would introduce songs on his radio show, whispering into the microphone, ‘Listen to this, Jerry!’” – but he wanted Stone to focus his profligate talents. “I’d tell Sly, We need to start a band! He’d answer, ‘I’ll send for you when I’m ready.’”

That call finally came in 1966. Stone assembled members of Freddie & The Stone Souls – led by Stewart’s younger brother Freddie, and featuring a 17-year-old Greg Errico on drums – and refugees from Stone’s recently-split Sly & The Stoners, including trumpeter Cynthia Robinson and bassist Larry Graham. “It was a unique mix: male and female, black and white,” remembers Errico. “We didn’t even play music that first night, just talked about everything we were gonna do. But as soon as we started rehearsing, we discovered a natural chemistry.

Within a month the nascent Family Stone scored a residency at The Winchester Cathedral in Redwood City, playing from 2 until 6am. Captured on newly unearthed live album The First Family, those combustible, frenetic Winchester nights made The Family Stone the hit of the Bay Area, winning the ear of Epic Records A&R (and soon-to-be Family Stone manager) David Kapralik, and a recording contract. Stone made the most of this opportunity. Though recorded on a day off from their residency at Las Vegas’s Pussycat a-Go-Go, in the label’s oldest, tiniest studio, Sly & The Family Stone’s 1967 debut, A Whole New Thing, was ambitious and eclectic, fusing psychedelic pop, Stax-y R&B and mutant funk. But was it too much?

“Sly adapted real quick. He just said, ‘I’ll give them what they want,’ and wrote Dance To The Music in four minutes.”

Jerry Martini

“We loved it,” says Errico. “Musicians loved it. But nobody bought it. David Kapralik said, ‘We need a hit with some hooks to grab everybody’s attention, to lead them up the path you’re going.’”

The feedback left Stone “heartbroken”, Martini says. “But Sly adapted real quick. He just said, ‘I’ll give them what they want’, and wrote Dance To The Music in four minutes.”

The track was everything Kapralik asked for, and more, becoming their first US Top 10 single. And while the accompanying Dance To The Music album and 1968’s more eclectic Life scarcely grazed the charts, Stone was on the edge of triumph. Released in May 1969, Stand! was Sly & The Family Stone’s first masterpiece, focusing on the tensions then shaking America over furious funk, anxious soul and sweet, life-affirming pop. There was darkness, in the form of the simmering Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey. But Stand!’s central message was one of hope and reconciliation, made explicit on the album’s lead single, Everyday People. On Stone’s first Billboard Number 1, he marked himself out in an era of divisions by championing “different strokes for different folks”, and telling his listeners “I am no better and neither are you/We are the same, whatever we do.”

Errico and Stone, 1968

On December 29, 1968, The Family Stone performed Everyday People for the first of three appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. “I’d watched Elvis be introduced to America on Ed Sullivan, and The Beatles,” remembers Greg Errico. “Back then, if you played Ed Sullivan, the world saw you.” But the pressure didn’t shake the Family Stone’s resolve. “We decided we were just gonna do our thing, which felt like magic every time we played.”

In fringed red leather vest and chains, L-shaped lambchops and Afro, Stone must have startled the more conservative of Sullivan’s viewers. But he opened with words from Are You Ready, off Dance To The Music: “Don’t hate the black don’t hate the white/If you get bitten, just hate the bite.” If previously he had been preaching to a mainly converted congregation of American freaks and heads, here was his message reaching the living rooms of mainstream America. And its gatekeepers, the broadcasters, seemed eager for more.

The following March, the band returned to the Sullivan show. “Sly said, ‘Just pay attention. I might do something – I just don’t know what it is yet,’” Errico remembers. During the breakdown of Love City, Stone grabbed his sister Rose’s hand and swept into the studio audience. As the TV cameras swung after them, the duo danced up and down the aisles, rousing the audience to clap and “spell out ‘Love’ for us just one time – L.O.V.E.!”

The Family Stone, ’68, now with Rosie Stone (centre).

“It was powerful,” Errico says. “Ordinary people were still very conservative then – everybody wore ties! Now look how we were dressed.” Glittery gold pants, silver and purple-striped dungarees, red-fringed knee-high boots – not a tie among them. The cameras loved The Family Stone, Sly in particular – and the feeling was mutual. “Sly embraced celebrity,” Greenman says. “He went on every talk show, and was the best guest of his time, for his charisma, his intelligence.”

Funny, razor-sharp, Stone was able to speak street wisdom without spooking interviewer or audience. He stood on the frontline of a culture war, knowing his Family Stone had their part to play. There were frightening moments along the way – Martini “almost got killed five times” in face-offs with racists on the road. But, says Errico, “we just skated through it all, somehow. We seemed to have this other-worldly power that got us through.”

In the most pointed testament so far to their crossover appeal, The Family Stone were booked for August 1969’s Woodstock festival. Sly was one of notoriously few black stars to play.

“The big joke about Woodstock is nobody who was there can remember it,” smiles Jerry Martini. “But I remember it like it was yesterday.” The group arrived via helicopter, Errico witnessing “a sea of almost 500,000 people below us, and this purple haze hanging over them as far as you could see”. There was apprehension, however – after two days of peace, love and music, the weather had turned, and The Family Stone didn’t walk onto the rain-sodden stage for their Saturday, 8pm slot until after three in the morning. “The sound people were on acid,” Martini adds. “Everybody was on acid back then, though we weren’t.”

Just before they hit the stage, Stone delivered a pep talk. “We all looked at each other and realised, all we could do was give it all we had,” says Errico. “It stopped raining – the universe blessed us with the moment. And the kids started getting out of their sleeping bags, getting into it, dancing. You could feel the wave of energy as they responded.”

Electrifying footage of the band playing I Want To Take You Higher, preserved on Michael Wadleigh’s concert movie Woodstock, backs him up. Even Wadleigh’s innovative split-screen filmmaking technique couldn’t entirely contain the full, funky kaleidoscope of The Family Stone at their peak. “By the end, we were like a locomotive up there on-stage,” says Errico.

But in the months that followed Woodstock, Sly Stone began to go off the rails.

Be yourselves: The Family Stone sticking together, 1971 (from left) Errico, Sly, Robinson, Freddie, Rosie, Martini, Graham.

Sly Stone announced late in 1969 that he intended to relocate from San Francisco to Los Angeles, to be closer to the industry. “We all looked at each other,” remembers Errico, “like this could be the beginning of the end. Sly was focused, a strong person. But he was also vulnerable.”

As Errico saw it, Stone had papered over his vulnerabilities, his insecurities, by splitting his identity in two. ‘Sylvester Stewart’ was their friend, the guy who wrote and produced the songs. ‘Sly Stone’ was the alter ego he assumed on-stage and on talk shows: impenetrable, larger than life. “In LA, away from the people who knew him, he was Sly Stone every day.”

“The ‘Family’ thing fell apart after that,” adds Martini. “LA changed Sly. Though he was still sharp and still wrote great songs.”

He was about to release one of his finest. Larry Graham’s portentous bass line was the heart of Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), which foregrounded the heavy, percussive sound he’d developed accompanying his singer mother, slapping his strings to compensate for the lack of a drummer. After basic tracking, Stone retreated to the studio alone for a fortnight, warning Martini, “I’m not coming out until I get what I’m hearing”. Two weeks’ obsessive re-editing and overdubbing later, Stone returned with a five-minute masterpiece of bruising, muscular funk that would redefine the genre.

But if the music was bold and powerful, the lyric acknowledged Stone’s anxiety over his split personality, his discomfort with fame, his sensation of the devil at his heels. “He’s reflecting on both sides,” nods Errico. “The light and the dark. But he sounds focused and determined. ‘This is how I’m going to handle it.’”

Stone set down roots in Los Angeles, moving into 780 Bel Air Drive – previously the home of John and Michelle Phillips of The Mamas And The Papas – and invited Martini and his wife to stay. “He gave us John and Michelle’s old room. It was filthy, dirty. I found their kids’ birth certificates. I found an ounce of cocaine, which Sly immediately confiscated.”

The Bel Air house attracted “all the pimps and the lowlifes, the drug-dealers and the murderers”, Martini adds. “They all idolised him. Geniuses like Sly attract the best people and the worst people.”

“I couldn’t get through to Sylvester, because Sly was in the way. The demon was always stronger.”

Greg Errico

Stone was now heavily into drugs, notably cocaine and PCP. “He was always very clear that he was a working addict,” says Greenman, “not the kind of guy to draw the shades and nod off all day.” But for all his industry, he was stalling on completing The Family Stone’s fifth LP. Their first four albums had arrived within 19 months of each other; now, two-and-a-half years stretched between Stand! and the November 1971 release of There’s A Riot Goin’ On, by which time The Family Stone had started to dissolve. Stone began turning up late to shows, or missing them entirely, an expensive habit. “Sly’s father, Big Daddy, was my roommate on the road, and he was really unhappy at how Sly changed,” says Martini. “Sly always had a heart of gold. But he’d changed.”

“Sly still had all these amazing creative talents, things to say and ways to say it,” agrees Errico. “But eventually, it got darker.”

Errico knows he appears on some of There’s A Riot Goin’ On, but the details are often hazy. The heavy fug that defines the sound and mood of the record also clouds memories surrounding the sessions, most of which took place at 780 Bel Air Drive. Previously, The Family Stone had recorded together live, to capture their energy. Now, Stone had them record their parts separately, to the electronic pulse of his Rhythm Ace, a primitive drum-machine. He would then mix and remix the tapes, and invite whoever was floating around his Bel Air abode to add parts. “We never planned anything,” Bobby Womack, an uncredited guest on Riot, told me in 2012. “I’d just turn up, see a guitar or a microphone, and play.”

By the time Riot finally hit the shelves, Errico was gone. “I no longer felt I could make a difference, to the business stuff falling apart, the disorganisation, the craziness that was happening. I had a vision of where this was going, and I didn’t want it. I did not want to go down with the ship.”

The album, meanwhile, was challenging, and heavier in tone. Stone’s opening words, “Feel so good inside myself/Don’t want to move,” signalled the downer vibe. “Riot wasn’t the cartoon image of the original Sly & The Family Stone,” says Errico. “It reflected what was happening.”

The mood in America was darkening, after years of unrest and the assassinations of key progressive leaders. Hope was being replaced by cynicism, and fear. Riot’s unease evoked the dwindling promise of the hippy era and the civil rights movement. “Stand! is the party,” says Ben Greenman. “Riot is the hangover.”

Sly and Tom Jones on The Midnight Special, December 1976

In May 1972, a 22-year-old drummer playing with Carly Simon drove up to 780 Bel Air Drive between sets at the Troubadour, on the advice of his friend, Pat Rizzo, then playing sax for The Family Stone.

“Sly was on his waterbed, unconscious,” remembers Andy Newmark. “I said, I hear you need a drummer – I’m the guy. He said, ‘OK, play.’ He had a set of practice pads by the bed, so I closed my eyes and played what I thought was a funky beat. I opened them again, and Sly was dancing to my beat. He looked happy. He said, ‘You’re the new drummer.’”

Newmark had been a huge Family Stone fan. “The band were magic,” he says. “But by the time I got there it was just Sly by himself. I arrived at the point where he was descending the mountain he’d climbed, into the darkness.”

Stone was at work on Riot’s follow-up, playing many of the parts himself. The Family Stone were disintegrating further – Larry Graham quit early in the sessions. The exit was fractious; rumours flew that Stone and Graham had taken contracts out on each other, though Stone pled innocence in his memoir. Now it was often Stone playing the bass, accompanied by his Rhythm Ace.

“Sly was very isolated, very much in his own world,” Newmark remembers. “He was making records alone – it was all completely fractured. I never saw any of the band members in the recording studio.” Sessions would run through the night, and often Newmark arrived to find Stone had re-recorded all the parts to the song they’d recorded previously. “It kept going, month after month, the songs mutating. The only reason he stopped after a year is Epic cut him off.”

The drummer struggled to strike up a rapport with his new boss. “Sly was very inaccessible. He was not going to reveal anything of himself.” They grew no closer as the group toured the album now quixotically titled Fresh.

“We never missed a show,” Newmark says, “but Sly just seemed like he wanted to run away and hide from the world.” The tour ended in December 1973, and when his cheque bounced, so did Newmark, on his way to stints with Ronnie Wood and David Bowie.

In court on drugs charges, 1989

“Everybody, including myself, was doing coke back then,” says Newmark, “but everyone was on planet Earth. Not Sly. He was in another world.” The drummer remains proud of Fresh, however. “Miles Davis loved Fresh. Sly played him the acetate at his apartment on Central Park West, and Miles took it to his band and made them listen to it. Twice!”

Fresh would prove to be Stone’s final musical triumph. 1974’s Small Talk has its moments, though Martini is reluctant to discuss it (“Just did my part,” he texts after our interview. “Not a good time in my life”). From there, recordings taper off, though Stone’s genius glimmers from time to time. He abandoned the last album credited to Sly & The Family Stone, 1982’s Ain’t But The One Way, leaving it to producer Stewart Levine to complete. It features a 45-second, presumably autobiographical, fragment titled Sylvester, where Sly intones “He’s a stranger, but mother dearest still knows his name…” Ben Greenman describes it as “this literary, poetic moment about what Sly became, what he left behind, and how he split himself into ‘Sly’ and ‘Sylvester’. It’s like an experimental film.”

Sly resurfaces at the 2006 Grammy Awards.

Through the ’80s, Stone allied with another funk maverick, George Clinton, squeezed songs onto a couple of film soundtracks and guested on albums by Jesse Johnson, Earth, Wind & Fire and The Bar-Kays. “You could build an album from those ’80s tracks, a coherent work, with a lot of his old themes,” says Greenman. But Stone never recorded another full album. “In some alternate universe, Sly kept making records,” Greenman sighs. “And they were great.”

In the real world, the decades that followed wore hard, as Stone struggled with addiction, ill-health, homelessness and lawsuits. In 2006 he resurfaced during an all-star tribute to The Family Stone at the Grammys in platform boots, a silver robe and a mohawk. Fitful touring followed; Errico rejoined the fold for 2010’s Coachella. “Have you seen the footage?” he sighs. “I had tears running down my face at the end. It just kind of dissolved on-stage, into a puddle. Once a decade I’d try to make it grow again. But I couldn’t get through to Sylvester, because Sly was in the way. The demon was always stronger.”

Stone kept making music, however, alone or with collaborators. Unreleased tracks he played Greenman while working on his memoir were, says the writer, “of a piece with his canonical work, grappling with the same themes, because he believed them so devoutly. Those ideas and convictions outlasted a lot of the disruption in his life.”

Los Angeles musician Sal Filipelli recorded a number of tracks with Stone in the 2010s, the final music released in his lifetime. Though he’d heard Stone was “this ‘Howard Hughes’ character, walking around with Kleenex boxes on his feet,” Filipelli says Stone remained plugged-in and creative. Filipelli last saw Stone in person in 2016, but they stayed in touch. “I got the sense that Sly felt he’d entertained people his whole life,” he says, “and now he wanted to relax and be entertained, watch TV and have his family around him. To take it easy.”

By the time the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease he’d been battling claimed his life, Stone was several years clean and had, according to Martini, “found peace”. Errico agrees, though finds it hard to shake feelings of regret. “If only he’d gotten into a programme sooner,” he sighs. “There were stronger elements that were in control, I guess. But the change in him the last few years, after he finally got straight… I look at the most recent picture of him with his kids, there’s this gleam in his eye.”

For Martini – taking a break from preparing to play Amazing Grace at Stone’s funeral to speak to MOJO – the legacy of Stone’s music could never be tarnished. “Sly always wrote what was on his mind and on his heart,” he says. “He was a true genius.”

IMAGES: SHUTTERSTOCK/GETTY/ALAMY