Mojo

FEATURE

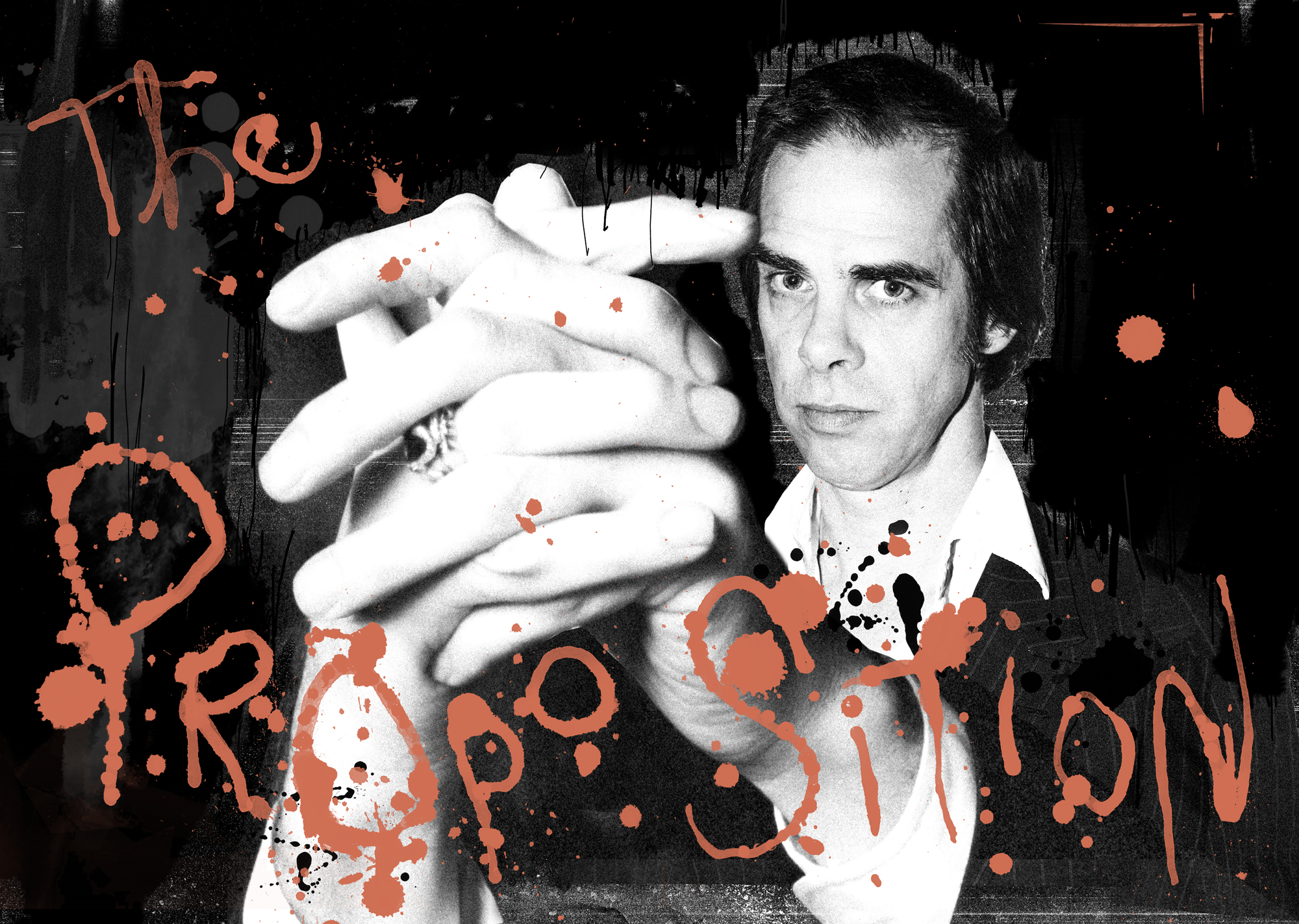

The Proposition

It’s been an odyssey from the heroin addiction and on-stage violence of The Birthday Party to life as a nine-to-five songwriter with The a Seeds. In 2004, with his roll-ups, cups of tea, family life, a film in production and one of the finest albums of the year, Cave opened up about art school, drugs, religion, his father and being a good dad.

Words: Phil Sutcliffe

Nice of MOJO to do a painting of me,” says Nick Cave, referring to the angelic illustration which accompanied MOJO’s review of Abattoir Blues/The Lyre Of Orpheus. “But why did you give me truck driver’s arms? I’m well known for having very thin arms?”

He spreads the maligned limbs wide. His dark jacket’s tightly tailored sleeves prove they are indeed pipestems. But that’s art for you.

Despite MOJO’s unwarranted slur on his dark-night, dissolute image, he’s smiling – it was a glowing review after all. This is cheering from one whose reputation rests on exploring shades of gloom with a sense of humour, which comes in any colour you want, so long as it’s black.

The bleaker aspects of Nick Cave’s legend date from his time with Melbourne mates The Birthday Party – who broke up in 1983 – and the 20-year heroin addiction which began in the late ’70s. But he’s all right now. At 47, he has a wife, Susie, and twin sons, Earl and Arthur, aged four (as well as two teenaged boys, Luke and Jethro, by earlier relationships). His songwriting is much admired and always developing. His band, The Bad Seeds, serve his songs, rarely get a solo and like it that way.

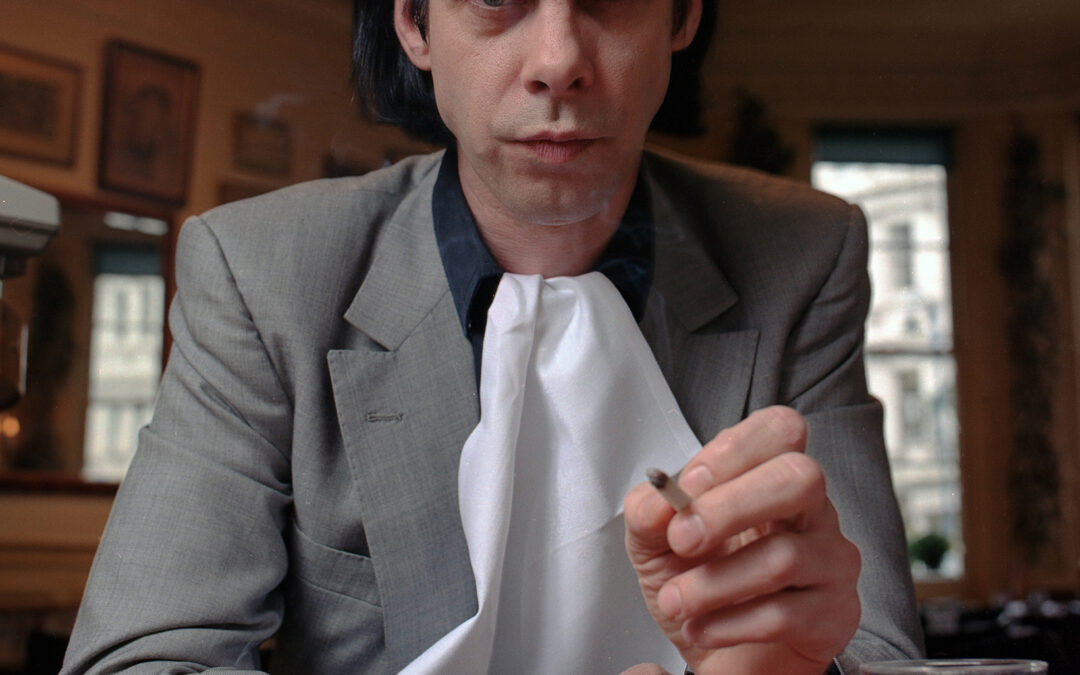

Seated on a sofa in the upper room of a smart West London pub, he picks at a plate of kebab and rice, pinches MOJO’s big chips, drinks tea and smokes roll-ups. Periodically, he looks up from under his black eyebrows towards his almost supernaturally jet hair, and greets MOJO’s latest poser with a grin that seems to relish the comic ins-and-outs of more or less everything.

You’ve been telling everyone your new album is “a masterpiece” and “a work of genius”. Have people been shouting “Oi, big ’ead!” at you on the streets of Brighton?

Hmm, I don’t remember calling it either of those things. But yesterday we were rehearsing for our tour and those songs were a real pleasure to play, which was further proof… that it’s a masterpiece and a work of genius. We recorded it fast and spontaneous. Ten days for a double! But the writing was very considered. I kept going back and back to the lyrics until I’d chopped away all those lines that don’t really mean anything, plus the odd unintentional quote. Sometimes I see a line in a poem and think “Fuck, that’s really nice”, so I whack it in a notebook. In a song called Loom Of The Land [on Henry’s Dream], there’s a bit about the poplars “turning their backs”. Recently, I was re-reading Lolita for the millionth time and there it was, “The poplars turned their backs”. I got rid of that stuff this time. Except in Supernaturally there’s “You are my north, my south, my east, my west” from Auden’s poem Funeral Blues. That’s a deliberate – what’s the nice word? – reference.

For several albums you’ve been writing in an office on a nine-to-five routine, which suggests a change in you – you once said, “The idea of a calmer life frightens me more than anything else. It’s inherent in my character to destroy that.”

I really don’t know what that means. But I’ve been using the office for about six years, since I met my wife. As soon as I started living with her it became clear to me that I wouldn’t write under those circumstances. I don’t feel the creative process is something you do around people you love. It’s undignified. The screaming and crawling the walls and tearing your hair out and cursing. There again – call me old-fashioned – I do see the idea of organised work, as creditable, even noble, romantic.

Romantic? A factory worker will say, “Sod that, squire.”

Well, a factory worker, I assume, does something he doesn’t particularly want to do. I don’t. I go into the office and my work, it… transports me in some way.

Do you distract yourself? Do you have a radio or TV?

I have a desk, a piano, a telephone, books. I don’t use the phone so much now. I had a friend, Mick Geyer, who died recently. I used to talk to him for at least an hour every morning. And I’d play the piano and sing at the phone (he hunches up and twists around to demonstrate). I’d say, “What d’you think of that one?” He’d say, “I think it needs a bit of work, Nicholas” or “You’re onto something there, mate”. I had a complete respect for his opinions. He spent his time looking for obscure and delightful music which was an enormous part of my development. I don’t do that. I don’t have time and I don’t have his adventurous spirit. The album’s dedicated to him.

The office must be a lonelier place now.

It is. I don’t know how else to write, though. The idea of sitting around with your mates and knocking out a song appals me. I have written songs on beer mats, but I always ended up at the fucking typewriter working it out. Whatever was going on in my life. There were periods when I could have loosened up a bit, when I was over-involved in the English language. Proofreading my lyrics for the Penguin collected works, sometimes I thought, “Fuck! This guy needs a night’s sleep!”

Your writing style was probably at its most extravagant during the ’80s when you were reading Deep South novelists like Flannery O’Connor and Carson McCullers and writing your own novel, And The Ass Saw The Angel (1989). Lately, it looks as though that influence has faded.

Southern literature deals with grand themes in hyper, extreme prose. That’s why I responded to it and certainly I would relate to that in the way I write today. To get into one of my records, you have to enter my world, an alien, romantic, extreme world of my making. You don’t drag one of my records into your world. I think that’s why, to a degree, my music will always be marginal.

“Beaver Mills was a little rat-faced guy and he carried a knife. We had several fights. I beat him once. I wasn’t good, but I did have spirit.”

Nick Cave

And you absorbed all those influences into your novel and your songwriting while only ever visiting the South for one gig?

Yeah, it was totally based on received information: movies, books, blues music. I was creating something unreal, mythical. I didn’t think research was necessary… although I do remember ringing my mother, who’s a librarian, and asking if she could find out something about sugarcane growing because it was absolutely fundamental to the story. She sent me this two-page pamphlet for schoolkids and that was it.

Thinking of you creating “a world” for each album, you once said that one reason you took heroin was that it beat back “the voices” that were flying at you from your imagination.

That glorifies it somewhat, but it was true. It happened in periods where I would try to stop taking drugs. I felt besieged by an endless stream of prattling internal dialogue in my head. I couldn’t sleep. It got overwhelming and then… I was delivered into this place of peace for a while when I took smack. Eventually heroin just exacerbated the problem so I gave it up, to cut a long story short, six years ago. And I don’t have that bullshit in my head anymore.

You said you see the office routine as protecting your family from the stresses of your work. Aren’t rock stars meant to be above family responsibilities?

There’s a whole world within the family that is beyond anything I do workwise. I wouldn’t have had kids if I didn’t feel that way. There’s also a… My father was larger than life [adult educationalist Colin Cave died when Nick was 21]. When he entered the room he was Godlike to us all. I loved him very much, but in some ways his personality was so big that it sucked everyone else’s away. That was very much about his work. It’s important to me that I don’t affect my children in that way. That they are free to… blossom in the way they want to blossom.

There’s a story about your father in a new song, Nature Boy. As a kid, you see “some routine atrocity” on the TV and then, “My father said, don’t look away / You got to be strong, you got to be bold, now / He said, that in the end it is beauty / That is going to save the world, now”.

I was at my grandmother’s house. On the TV news I saw the attempted assassination of George Wallace [in 1972; Wallace was a racist ex-Governor of Alabama who regularly stood for the Presidency]. I was shocked because I knew it was the real thing. My father said, “Yeah, this goes on, but there are beautiful things in the world too.” You hang on to a memory like that.

You’ve often said you rate yourself as a father.

The revelation is, I always thought my parents knew what they were doing and suddenly I realised they didn’t and I don’t – you’re fucking winging it! (Laughs) That endeared my parents to me and reconciled me a lot.

One thing having children must challenge is the creative artist’s egocentricity.

Writing can be incredibly selfish because you have to spend much of the day examining yourself, plumbing the depths of yourself. On one level, I find that nauseating.

Has fatherhood and marriage affected you as an artist?

It’s made me better. It’s deepened me. You have to compromise. And compromise can actually be strengthening when you see there’s something greater going on in a marriage than the two parts, which is the marriage itself. Does that make sense? I’ve always written songs about love, but I’ve written about the beginnings of love and the ends of love. There’s this whole middle section that hasn’t really been examined in rock’n’roll. It’s harder. It’s less dramatic. But I’ll give it a bash.

Love gets a fair kicking in your earlier work. Isn’t it something you’ve been extremely suspicious of?

There’s certainly a nice sense of drama in letting the whole thing explode. So, yes, it gets a kicking. But while I was writing those songs I was falling in love every week. I had anything but a cynical attitude to love. Although I suspect what I thought was love may not have been love.

In your songs, the big move away from the feeling that we need love but it’s impossible comes with Into My Arms from The Boatman’s Call (1997), where you actually say, “I believe in love”.

It came out of a very wounded period [after the break-up of relationships with Viviane Carneira, Luke’s mother, and then with Polly Harvey]. That album has the whole gamut going on. Well, it has the beginnings and the ends (grins). No, I think I’ve always had faith in the idea of love.

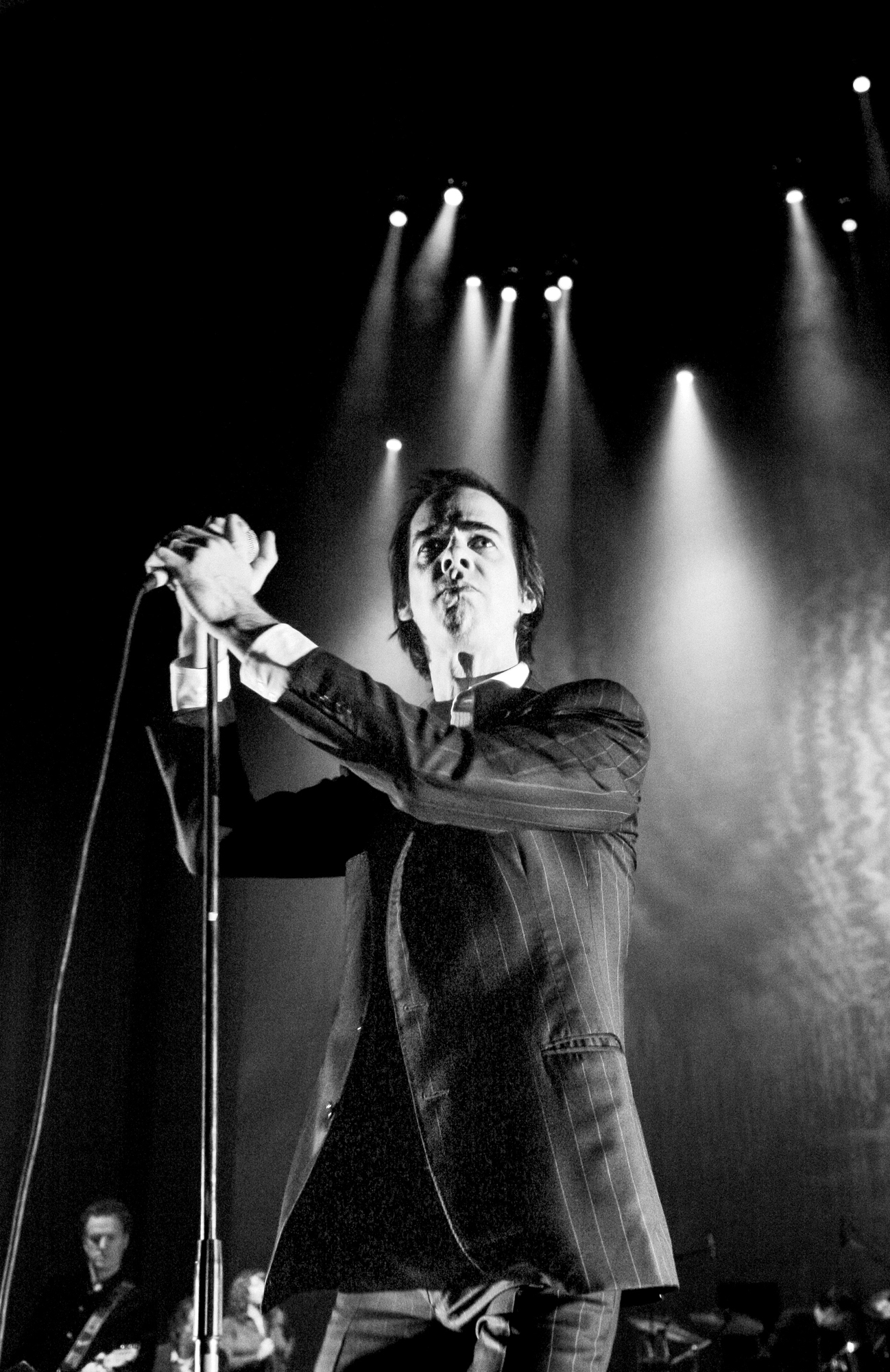

Playing live at Brixton Academy, London in 2004

Do you know what set you on the road towards being an artist?

I always wanted to be a rock star. But I wasn’t that musical. I was quite good at painting, so that became my chosen field. And then I failed art school and, at the same time, this band I was in [The Boys Next Door] started to take off so I got involved in the music business – which I am very happy about.

But were you disappointed at the time?

I was outraged that I failed art school. I was fuckin’ mortified. But, uh, I’m slowly getting over it.

Back then you talked about discovering “the joy of displeasing somebody”.

We had that twofold. In art school there were a couple of fairly conservative teachers and we took great joy in painting things that offended them – such as penises. And with the band we were playing Australian beer barns so we were weaned on being booed, people sitting there shouting, “Get off you wankers!” Something about that felt really good. Displeasing people keeps you awake, with a good healthy fuck-you attitude.

You did an impressive amount of fighting at school – apparently, the main event was a scrap with a lad called Beaver Mills?

Great name. I did fight a lot, but I was forced to. I was a boarder for one year and boarders always fought wars with the day scabs as we called them. Then the following year I became a day scab myself. Awkward situation. Beaver Mills was a little rat-faced guy and he carried a knife. We had several fights. I beat him once. I wasn’t very good, but I did have a certain spirit.

In The Birthday Party years you seem to have been a violent fellow, too, forever jumping into audiences at gigs and punching fans.

Allegedly. On one tour of Europe some promoter billed us as “the most violent band in the world”. It was an open invitation to conflict. We had an ex-marine fan called Bingo who used to keep an eye out and disarm the front row. Backstage he would show us the iron bars and whatnot he had confiscated. I’m not saying I didn’t play my part in it, but for self-protection sometimes you have to do, uh, pre-emptive strikes. Take ’em unawares (laughs).

It must have been a rough life. Did you enjoy it?

We had a good time. Eventful. Although after a while it became a little predictable, people coming along to fight the band. I guess that’s why The Birthday Party broke up. When we started The Bad Seeds it was different. We just plough our own lonely furrow. We’ve been around for a long time and there have been periods when we’ve been hopelessly irrelevant to what’s going on. When we did the Lollapalooza tour in America [in 1994] – 53 dates, I remember – grunge was happening, not one person there in long trousers, and they went for lunch while we played, then came back when we stopped (laughs). I found it extremely difficult, but, contractually, we couldn’t pull out. It was years before we went back to America.

Your conspicuous drug-taking, in The Birthday Party and beyond, gave the appearance of being self-destructive, maybe of a piece with the way Keith Richards used to talk about himself as a “human laboratory”. Is that how it was?

No. I can understand that Keith Richards may have seen himself that way because he was a forerunner for white rock’n’rollers taking drugs. By the time we were doing it everyone was taking massive amounts of drugs so we were doing something tried and tested! I was a junkie. I was not particularly adventurous. I took heroin and I took speed. I didn’t smoke pot. I drank. It was kind of depressing (laughs). Well, the first 10 years were all right, the second 10 years were nothing to write about. But, to me, way too much has been made out of the drugs thing. When I grew up in Australia everybody I knew shot up heroin, it was the recreational drug. It was only when I came to England I realised it was probably the most anti-social drug you could take. You were marginalised. Junkies were down there with the paedophiles, basically.

“As a kid I liked the Bible stories because they were spooky, violent. To me, Christ seemed deeply human and fallible.”

Nick Cave

You’ve lived in Australia, the UK, Germany, Brazil. Was there anywhere or any time when you felt part of a community – in any sense of the word?

I’d have to say no. Not long ago I had this twinge about the place where I live, Brighton – that I felt a part of it, that I actually cared about it. A feeling almost of civic duty creeping in. Utterly foreign to me… except that within The Bad Seeds there’s always a very solid feeling of a group of men working together. We prize that. We’re very careful not to disrupt it by bringing personal problems to the band. A gang mentality, I guess.

Your songs have always dwelt on religion – usually in an ambivalent way. I understand The Bible first made an impression on you when you were a choirboy, but how did your beliefs begin to develop from there?

As a kid I liked the stories because they were spooky, violent. I don’t know whether I believed or not. But I started reading the Old Testament in art school because I found I had more of an emotional attachment to religious art than I did to a lot of modern art. Then, through the ’80s, writing the novel I read the New Testament very closely and I was… taken away by the life of Christ. To me, he seems deeply human, fallible, something one could almost aspire to.

What was your favourite Bible story?

The touching of the hem of the garment. Christ is in a throng of people. A girl who has had “an issue of blood” for 12 years reaches out and touches the hem of his garment. He turns and says, “You are made whole.” That notion of being made whole… that was the human nature of him.

Do you believe in God now?

I do, yeah. But it’s open, doubtful, sceptical. Although I’ve never been an atheist, there have been periods when I struggled with the whole thing. As someone who uses words, you need to be able to justify your belief with language. I’d have arguments and the atheist always won because he’d go back to logic. Belief in God is illogical, it’s absurd. There’s no debate, I feel it intuitively, it comes from the heart, a magical place, a place… of the imagination. But still I fluctuate from day to day. Sometimes I feel very close to the notion of God, other times I don’t. I used to see that as a failure. Now I see it as a strength, especially compared to the more fanatical notions of what God is. I think doubt is an essential part of belief.

On The Lyre Of Orpheus that more settled faith seems to bring a hint of preaching into your writing. In O Children you say “the answer is short, it’s simple, it’s crystal clear”. Aren’t you starting to tell people?

Maybe. There’s an element of preachification in that. But it’s also saying, we can’t find that answer, we’ve lost it. I don’t like being preached at and I don’t have the authority to tell anyone what to think. If I started doing that, it would take something away from my work. In O Children I don’t say what “the answer” is. What I value most about my work is that it retains a certain amount of mystery – which keeps you revisiting the record. But, uh, I do see it as my duty in some way to put forward my own notion of God. I don’t think it would be true to myself not to do that. It’s a genuine preoccupation. Always has been.

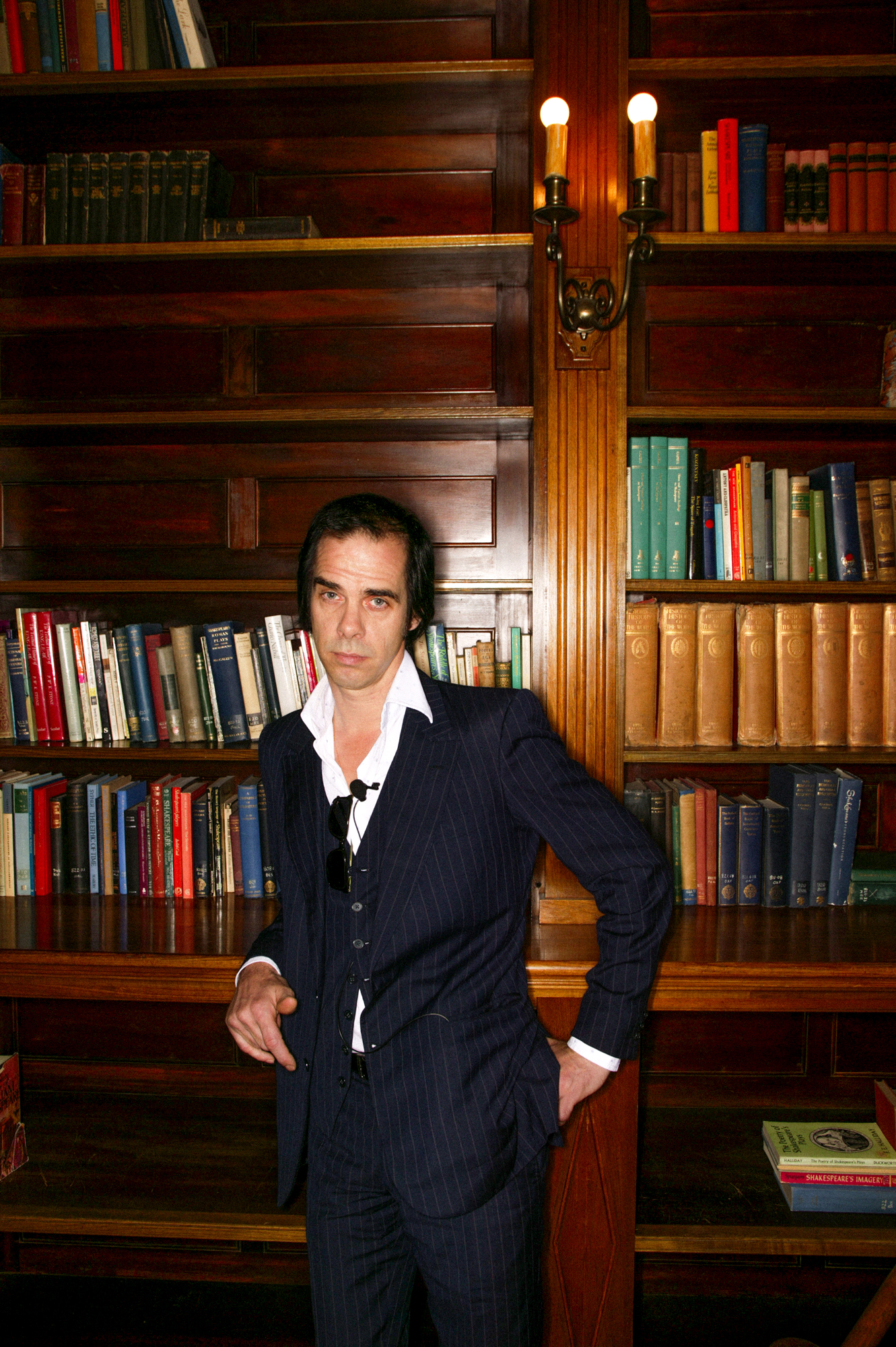

At the Final Last Words interview, Sydney, December 2004.

Do you have an overarching big idea about the value of music? In 1981 you said, “I want to write songs that are so sad, the kind of sad where you take someone’s little finger and break it in three places.”

I can’t add to that! I do like a sad song. I said that in 1981? There you go. I’ve always been miserable.

Well, on the new album, the song The Lyre Of Orpheus portrays music as a weapon of mass destruction which not only blasts Eurydice into the Underworld but massacres birds and bunnies too.

Yeah, but it’s a comic song, you know. I remember sitting in the office working on the last verse: “She said to Orpheus / If you play that fucking thing down here I’ll shove it up your…” I thought, “Arse? No. Bum? No.” Then I got it. “Orifice!” Fucking great! I took the day off after that.

But what about that big idea? How do you rate rock as an art form?

I had a lot of received notions about where rock music was on the creative ladder from my father and art school. Painters were up there. My father always put poets on the top rung. It took some time before it dawned on me that I was doing something as worthwhile, if not more so. Through what music did for me, I found it had a potential other arts don’t have, which is to utterly change you within three minutes. Your whole body chemistry can change, your mood, your perspective. I use music for that purpose. I know Dylan or Van Morrison or Nina Simone will make me feel… better. Music makes me better.

Have you ever heard anyone whistling one of your songs?

Er, no. I’d like to. Walking down the street, yeah. It would be nice.

Do you think you’ve become a good singer?

You don’t know how hard it is for me to say it, but yeah. I’ve always been bowed beneath the limitations of my voice and I’ve always felt that very deeply. But I like it now. Although tuning isn’t one of my great talents, and intonation isn’t either, I think I have a pleasing way of phrasing at times and I can be quite expressive. To a fault on occasion. It can become a little melodramatic. But I’ve finally accepted that my voice will always sound morose, melancholy, lugubrious, plaintive.

And now your first screenplay is about to be filmed. How does that compare to making music?

They’re already in the third week of filming, which is great news for me. It’s called The Proposition and it’s an entirely fictional story set in 1888 at the end of the bushranger era. I don’t think my script relates to my songwriting at all. Hopefully the characters aren’t just dribbling Nick Caveisms throughout. Johnny Hillcoat, the director, is an old friend who’s done a lot of Bad Seeds videos and he asked me to write it. It stars Ray Winstone, Emily Watson, Guy Pearce and John Hurt. A few weeks ago I went to Winton, this tiny town in Queensland where they were rehearsing, and it was fantastic – to have written something and see these actors do it, really great.

So that’s the movie, the novel and loads of albums. Which begs the question: when are you going to write your autobiography?

I did have an idea about going back through my life and interviewing people. But I abandoned it. Too much like hard work. And masturbatory. So. Fuck, no!

Overall, in many areas of your life – religion, music, relationships – you seem to have emerged from all kinds of uproar and confusion into a workable degree of self-respect and stability. Is that how it feels to you?

I feel more confident in the worlds I’ve created. A lot of it comes from narrowing down the experiences I actually have. I’m involved in my family and my work and some friends and that’s it. It’s simpler and it’s… intensified. And, in that respect, I’m happier.