Mojo

FEATURE

SONG OF THE MAGICIAN

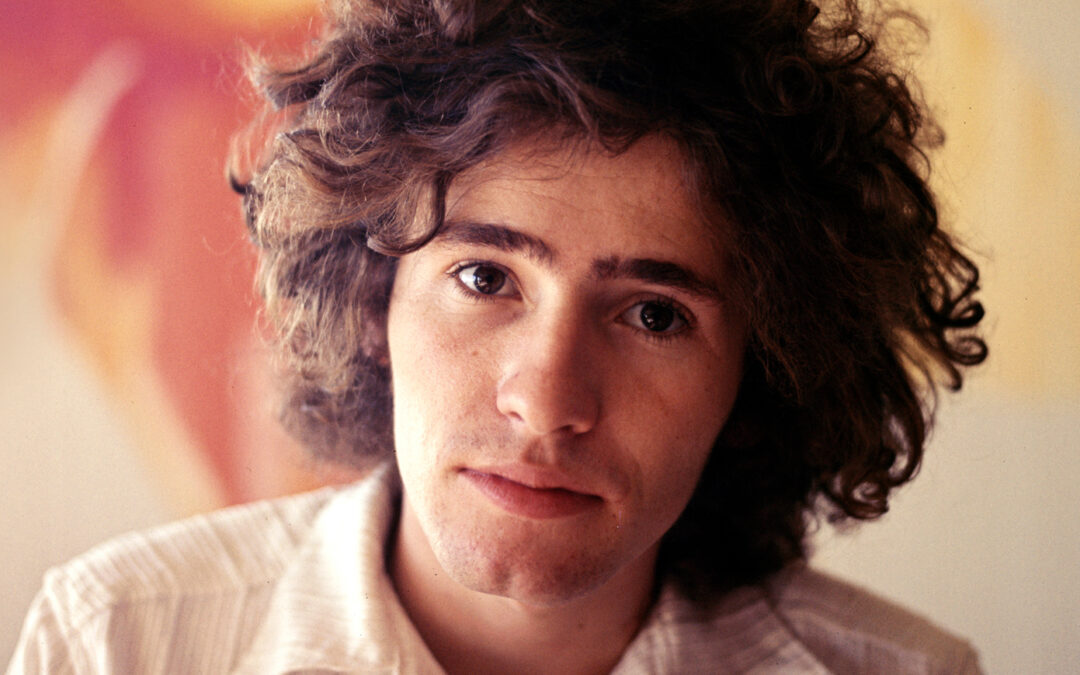

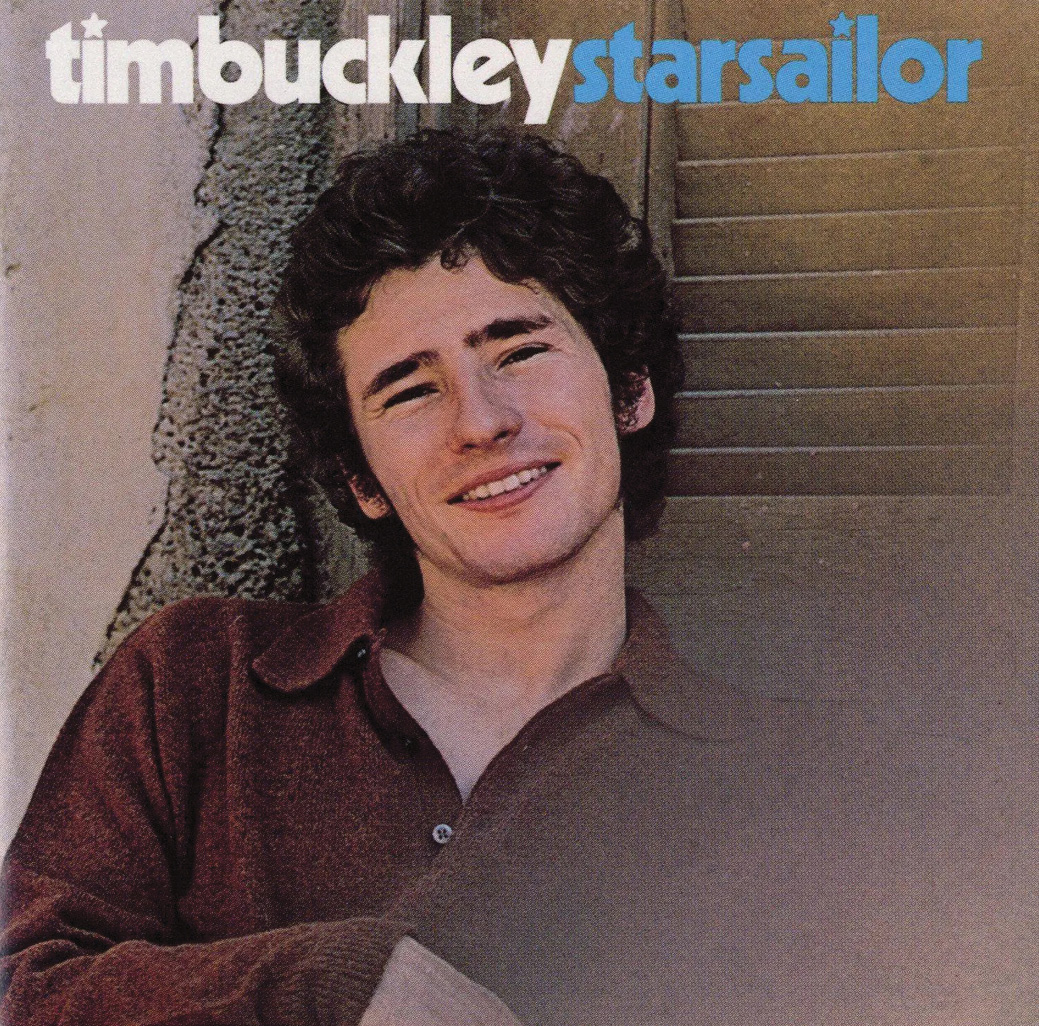

Fifty years since his tragic overdose, Tim Buckley remains the patron saint of musicians who risk everything to unlock transcendence, a quest encapsulated in his audacious mid-career masterpiece, Starsailor. Turning his back on fame and fortune, leaning into the unknown, was where he was lost but also found. “It was like he came into position of his muse,” discovers Grayson Haver Currin

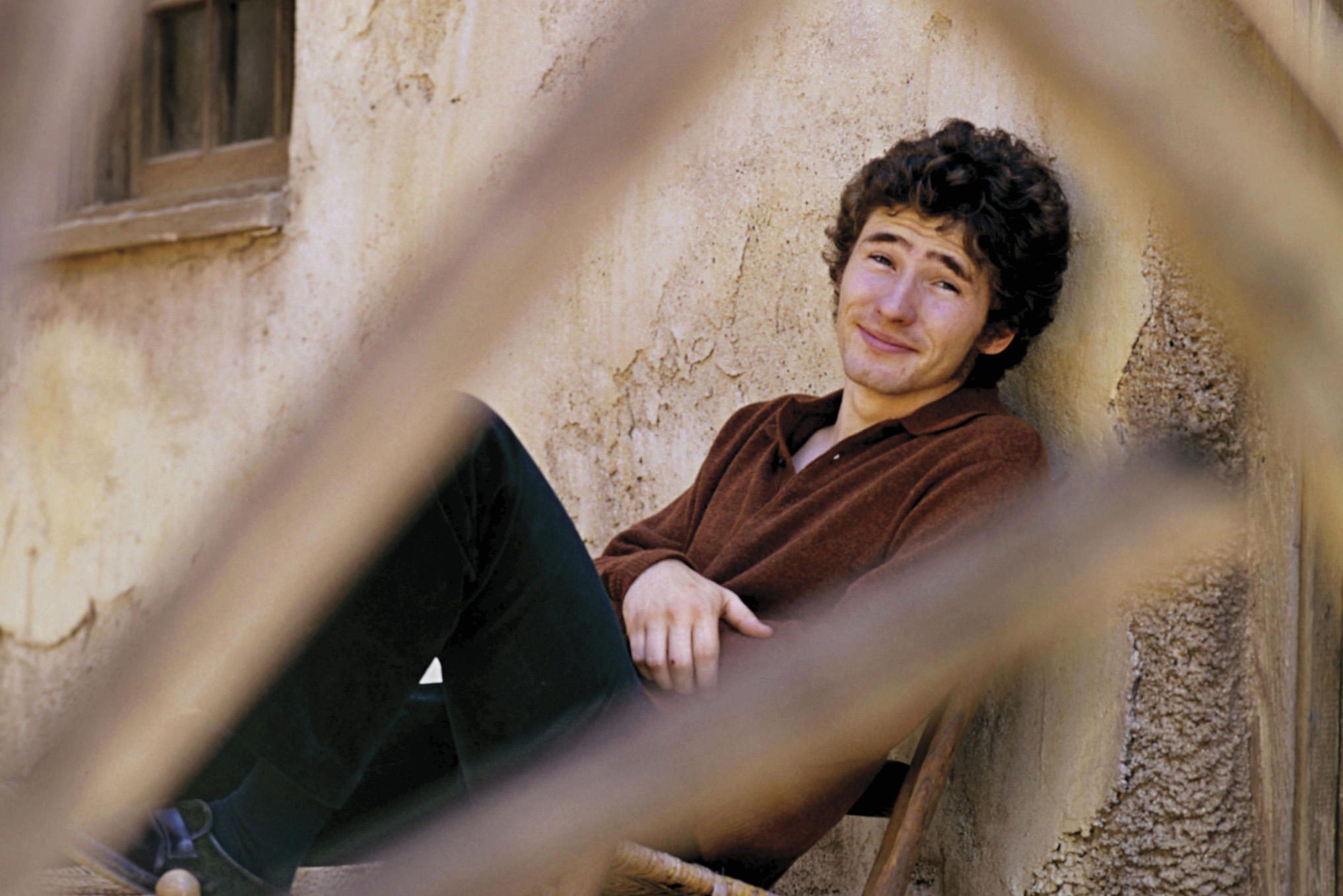

Portrait: Ed Caraeff

IT WAS THE SUMMER OF 1968, the Newport Folk Festival. Bob Dylan had started a revolution there three years earlier with his sunburst Fender. Tim Buckley, with his tidy curls and a 12-string acoustic, would suggest a subtler one.

“I’ll introduce a gentleman who, in the great Ogden Nash tradition of poetry, has been writing and singing his own songs in a fairly modern idiom,” announced that afternoon’s emcee, the songwriter Oscar Brand. “[It] sits, however, very, very comfortably on a fine bed of old folk music.”

Buckley, however, did not play old folk music that day. Backed only by street-savvy conga player Carter C.C. Collins and Juilliard-trained vibraphonist David Friedman, he prowled through the serpentine, then-unreleased Buzzin’ Fly, vibraphone tucked between chords like jewels. He strummed Wayfaring Stranger to pieces, then unfurled his voice in operatic arcs for The Dolphins, by his hero Fred Neil. It was aggressive, ecstatic, and urgent. The crowd exploded.

The set would have ended there had Brand not jumped in, suggesting an encore. Someone in the audience yelled for Morning Glory, the last track on 1967’s Goodbye And Hello. Buckley assented.

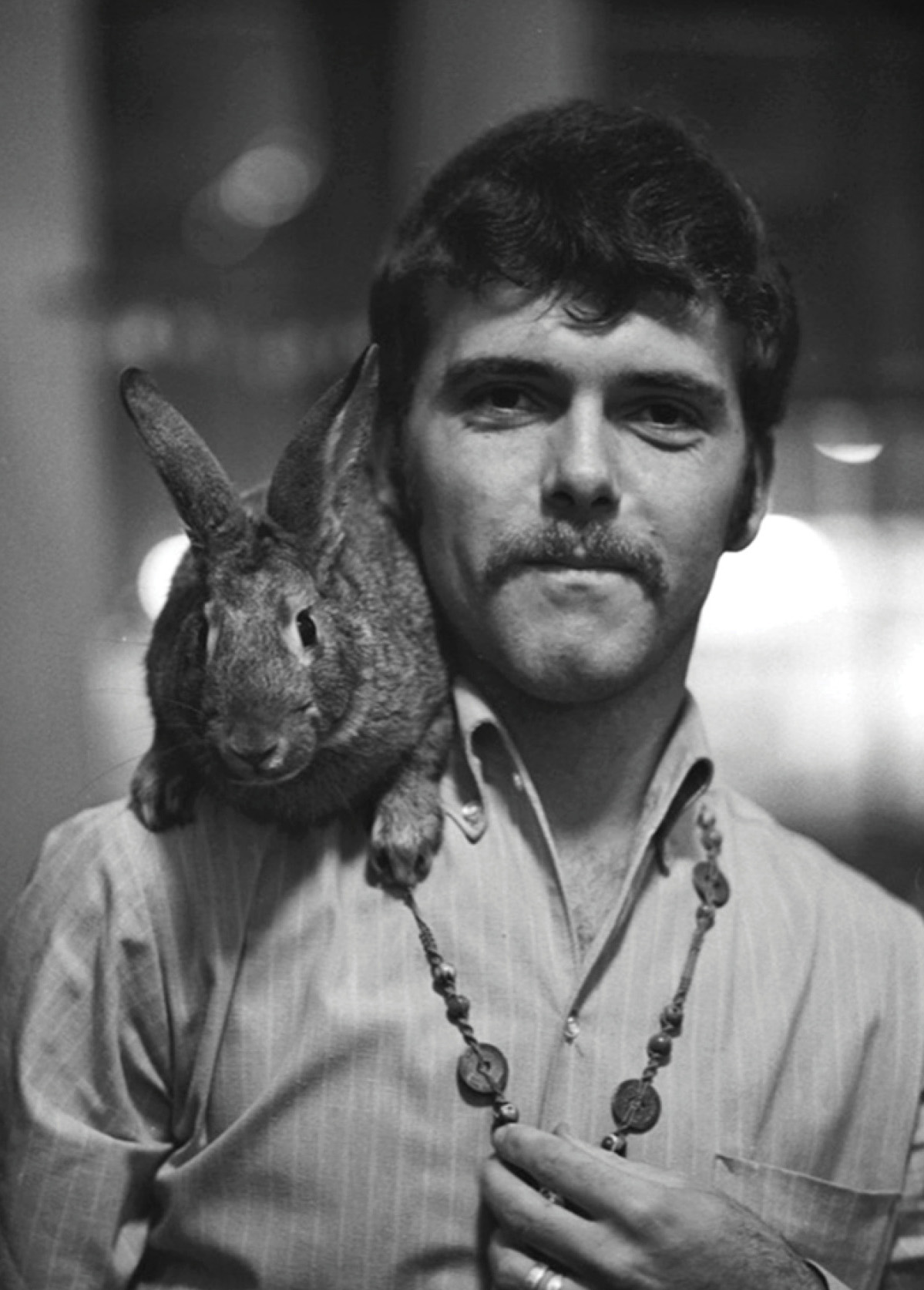

Heart and soul: guitarist Lee Underwood and furry friend, October 1967

“It was exciting, because it was new,” Collins tells MOJO from his home in Hawaii. “Nobody was using vibraphone in folk music, or whatever it is we were doing, these jazz players mixed with folk. It allowed us to take more adventures.”

“Show business is fine, but I’m pretty much involved in music alone – in playing it and performing it and in entertaining”

Tim Buckley

Later that year, Collins, Friedman, and Buckley were the core of the band that recorded Happy Sad, an impressionistic folk-jazz wonder about love lost and gained, rendered in Buckley’s messianic range – maybe as wide as five and a half octaves. A month before its release in April 1969, Buckley was already over that, too, plus the heartthrob scene his previous two albums had created. When a tall blonde fan rushed the stage to throw a red carnation at his feet during a set at New York’s Philharmonic Hall, the divorced father to a kid named Jeff whom he only met once scooped the flower, chewed the petals, and spat them out. “That really tastes terrible,” he said.

“I really wish people would try to live their own lives and stop trying to make musicians do it for them,” he told The New York Times’ Michaela Williams, who reported the flower-eating incident. “There’s a lot more to music than sex; I play heart music.”

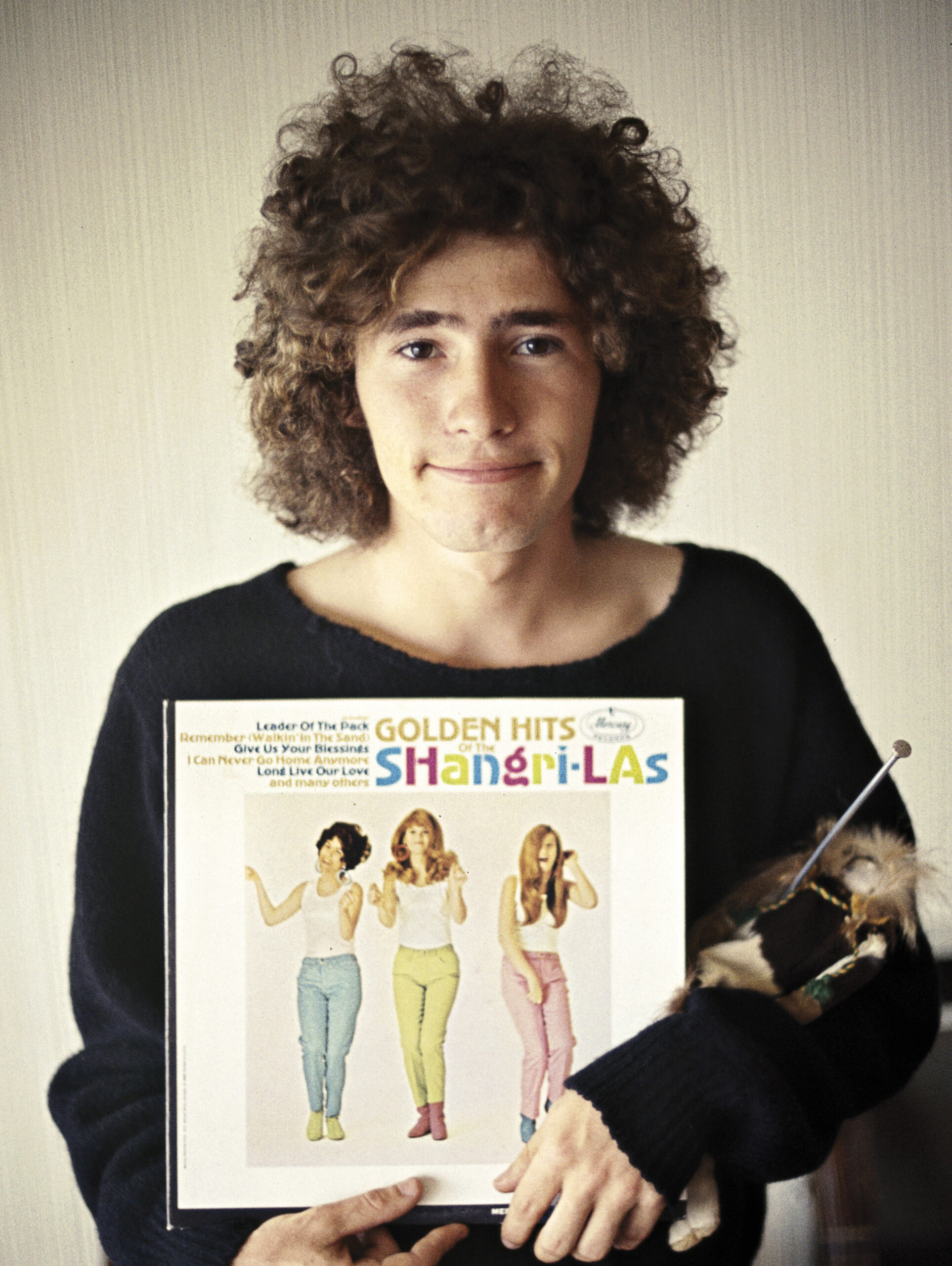

Buckley went on to say that his fans had forsaken the country’s prized jazz artists, raved about Milt Jackson and Miles Davis, and swore that he would soon step away from esteemed theatres altogether and into jazz clubs. “My new songs aren’t dazzling. It’s not two minutes and 50 seconds of rock ’em, sock ’em,” he said. “I guess it’s pretty demanding.”

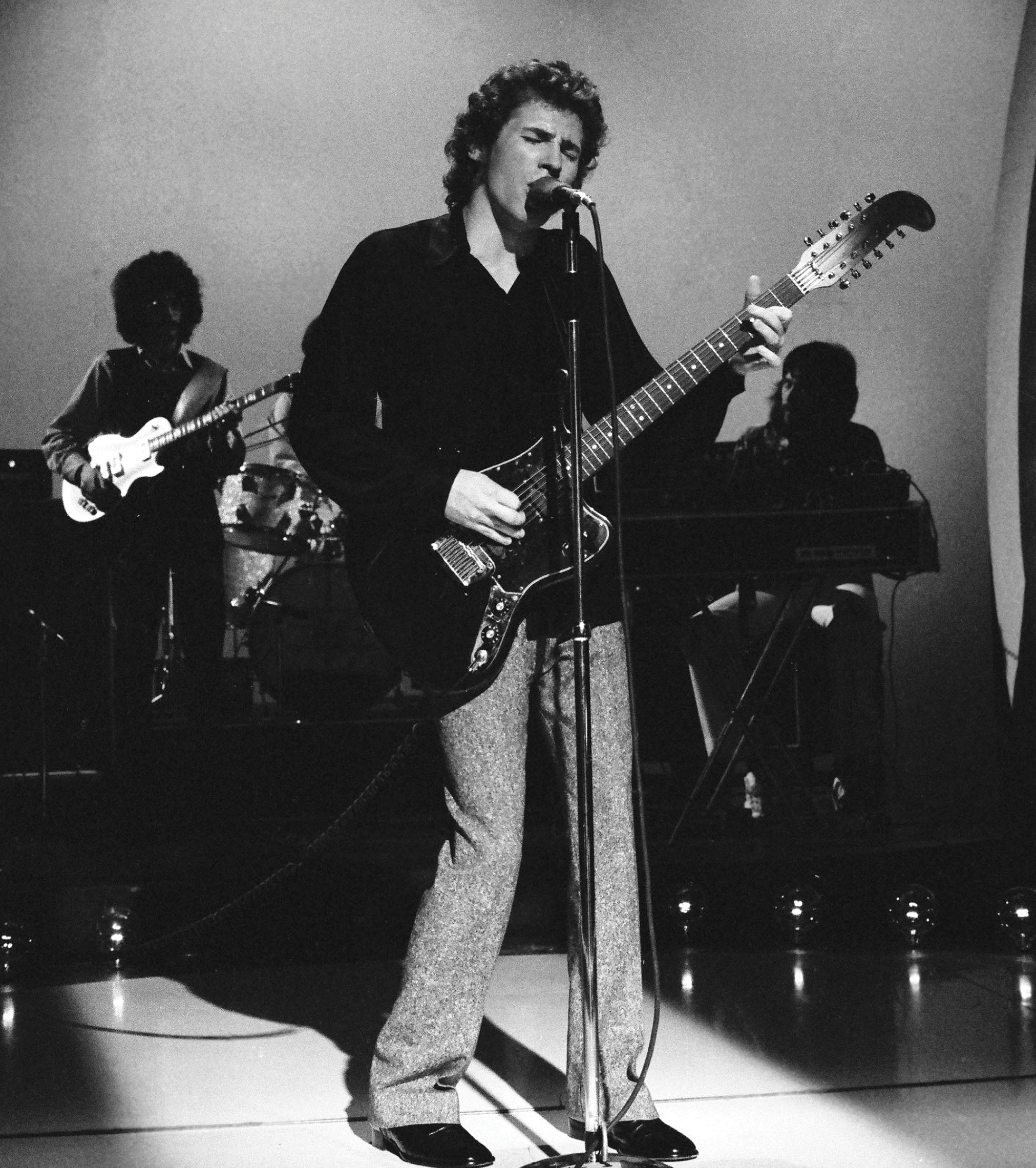

Buckley and conga player Carter C.C. Collins performing at the Bitter End, Greenwich Village, November 14, 1967

WHEN TIM BUCKLEY GAVE CARTER Collins a compliment, the conga player saw not only an in but his way out, too.

Collins had been raised in the foster care system of Boston and dropped out of high school. Street musicians captivated him, and he eventually joined them on drums, strapping his instrument to his chest everywhere he went. By the winter of 1967, he’d played with a few bands and singers, including Richie Havens, and was living rent-free at Bard College in upstate New York. When word came that Buckley, who had released his debut album months earlier, was coming to play, a few students asked Collins to join an ad hoc backing band.

“After four tunes, Tim was tired of it,” Collins remembers. The ensemble included Chevy Chase, Donald Fagen, and Walter Becker. “He waved the back of his hand toward me, put his guitar away, and said, ‘I only want him to play.”

With Buckley’s tight curls and serious visage, Collins assumed he was another Dylan knockoff. He was stunned by his vocal range and focus, plus the way his songs made people in Bard’s packed house cry. Buckley told Collins he liked him. “Why the fuck,” Collins responded, “don’t you hire me, then?”

““Rock? I’ve really never known a rock musician that I could talk to for longer than five minutes at one time. What is there to talk about?””

Tim Buckley

Two weeks later, Carter arrived in New York City to meet Herb Cohen, the impresario who had recently started managing Zappa and Buckley. Smitten with Buckley’s songs and face, Cohen saw a potential star and landed him a deal with Elektra Records. Collins was swept up in the gathering whirlwind of Buckley’s career – shows on both coasts, stints living together along the California shore in Venice, the June 1967 session for Goodbye And Hello.

“When an artist hears their first record, they sometimes cringe. That’s good, because then it means that the next one is going to be a lot better,” Elektra founder Jac Holzman remembered on a Buckley fan site in 1999. “That was the case with Tim… The second album had magic.”

Momentum was building. They played Carnegie Hall with Pete Seeger in the fall of 1967 and, six months later, played the chaotic first night at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, joining Albert King and Big Brother And The Holding Company. Buckley’s band briefly became regulars, supporting The Byrds and then Jeff Beck. (“Buckley has a tendency to meander,” Billboard said of that one, “but his lyrics pervaded the theater with strong effect.”) “It felt unprecedented to have a black man playing alongside a white guy in this folk world,” remembers C.C. Collins. “The audience response was incredible.”

These few months were critical for Buckley’s development. Since 1966, Lee Underwood had been his lead guitarist. When Underwood took a short break, though, the band needed something else. Collins had met Friedman, the vibist, through mutual friends, even crashing at his apartment. He encouraged him to see Buckley perform and, in turn, for Buckley to hire him. Half a century later, Friedman admitted he, too, thought Buckley was another Dylan stand-in.

Underwood returned in time to make Buckley’s third album at the end of 1968. This band – now with John Miller, a bassist who had just graduated from the University of Michigan and seen Buckley perform at the famous Canterbury House there – thrilled him.

“I talked about jazz, jazz artists, improvisation, the value of moving into improvisation to expand the total scope of the music,” Underwood says. “Timmy turned to me as a guru, giving him the confidence to see himself as a new composer. That album, Happy Sad, was his first major opportunity to get into jazz, Tim’s debut into serious improvisational work. We were moving in a new direction.”

Heart and soul: on-stage with Collins and vibraphonist David Friedman at the 1968 Newport Folk Festival

BUCKLEY HAD ALWAYS BEEN CAVALIER about his recording contract, but as the ’60s ended, he began to take the matter more seriously. For years, the company that would soon become Warner Bros flirted with buying Elektra from Holzman, who had launched it from his dorm room in 1950. Nearing 40, Holzman was looking to retire to a home he was building in Hawaii – and to secure global distribution for his company. He walked away with $10 million and a commitment to stay at the label for three more years.

“I knew Jac Holzman was going to sell his company, which really upset me,” Buckley recalled in a 1974 ZigZag interview. “I figured, Well, I’m going to do what I think is best and get a contract so that I can continue at the rate I was going.”

The new contract was with Straight Records, Herb Cohen’s novel partnership with Zappa to release records with some commercial appeal. Cohen wanted something from Buckley he could sell. There were two problems: Buckley owed Elektra one more record; and he had already assembled a band with something other than popularity in mind.

At home in Malibu, California, April 12, 1967.

Underwood had become friends with bassist John Balkin, an occasional Zappa associate who had recently formed a riotous and abrasive ensemble, Menage A Trois, alongside Buzz and Bunk Gardner, two brothers who played horns and winds in the Mothers Of Invention. When Buckley said he needed a bass player who would wade deeper into improvisational waters, Underwood had the guy. Balkin introduced Buckley to Cathy Berberian’s twisted interpretations of the works of her husband, avant-garde composer Luciano Berio. He was willing to try pretty much anything.

“We never had any music to read from,” Balkin told MOJO in 1995. “We just noodled through and went for it, just finding the right note or coming off a note and making it right.”

Underwood understood that his role as “guru” had been subsumed. Balkin would offer a bass line and tell Buckley to whistle or sing over it, then to change his key or tone and see what worked best, or how the pieces might cohere. Underwood had long encouraged Buckley to use his voice as an improvisational instrument; now it was happening. “Tim was soaring beyond whatever I knew, into new zones that Balkin knew,” Underwood says. “Balkin was a tremendous teacher. He wouldn’t teach notes to Timmy, but he would say, ‘Try this.’”

Recorded in bursts in the fall of 1969, the result – Lorca, named for the revolutionary Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, who, like Buckley, integrated surrealism into romantic lines – remains one of the most esoteric and electrifying label exits ever. With Underwood and Balkin on keys and Buckley pinballing between operatic heights and guttural gospel howls, the title track suggests serialism and acid experiments. A lament for the way love inevitably crumbles, Anonymous Proposition finds Buckley, Balkin, and Underwood conversing in rhythmic and melodic variations, the instrumentalists engaged in an intimate pas de deux with his improvisations.

It is tempting to see Lorca as some internecine exercise, made to waste Elektra’s money and prod Buckley’s audience, like the carnation in the teeth. But it wasn’t.

“I decided right then it was time to break open something new, because the voice with five-and-a-half octaves was certainly capable… We were getting real tired of writing songs that adhered to the verse, verse, chorus things,” he remembered in April 1975, drawing a straight line between its animating ideas and those of In A Silent Way, which Miles Davis released months before Lorca was made. “To this day, you can’t put it on at a party without stopping things; it doesn’t fit it.”

Buckley made Blue Afternoon, the straightest album of his career, for Cohen and Straight Records when Lorca was finished. Miller tagged in for Balkin on bass, while Friedman returned on vibraphone. These were largely songs Buckley had pushed aside as he explored improvisation. For Underwood, it felt like ceding freshly gained ground. His frustration is audible in the solo of So Lonely, Underwood overplaying as if he’s trying to cut the band free.

“That was a retreat into familiarity, into trying to get some commercially viable tunes. Tim needed something to give a commercial whoop-de-doo,” says Underwood. “I was dismayed with the notion of playing rehearsed music, but I kept my mouth shut about my needs to move beyond folk music, beyond commercialism, and just get into improvisation.”

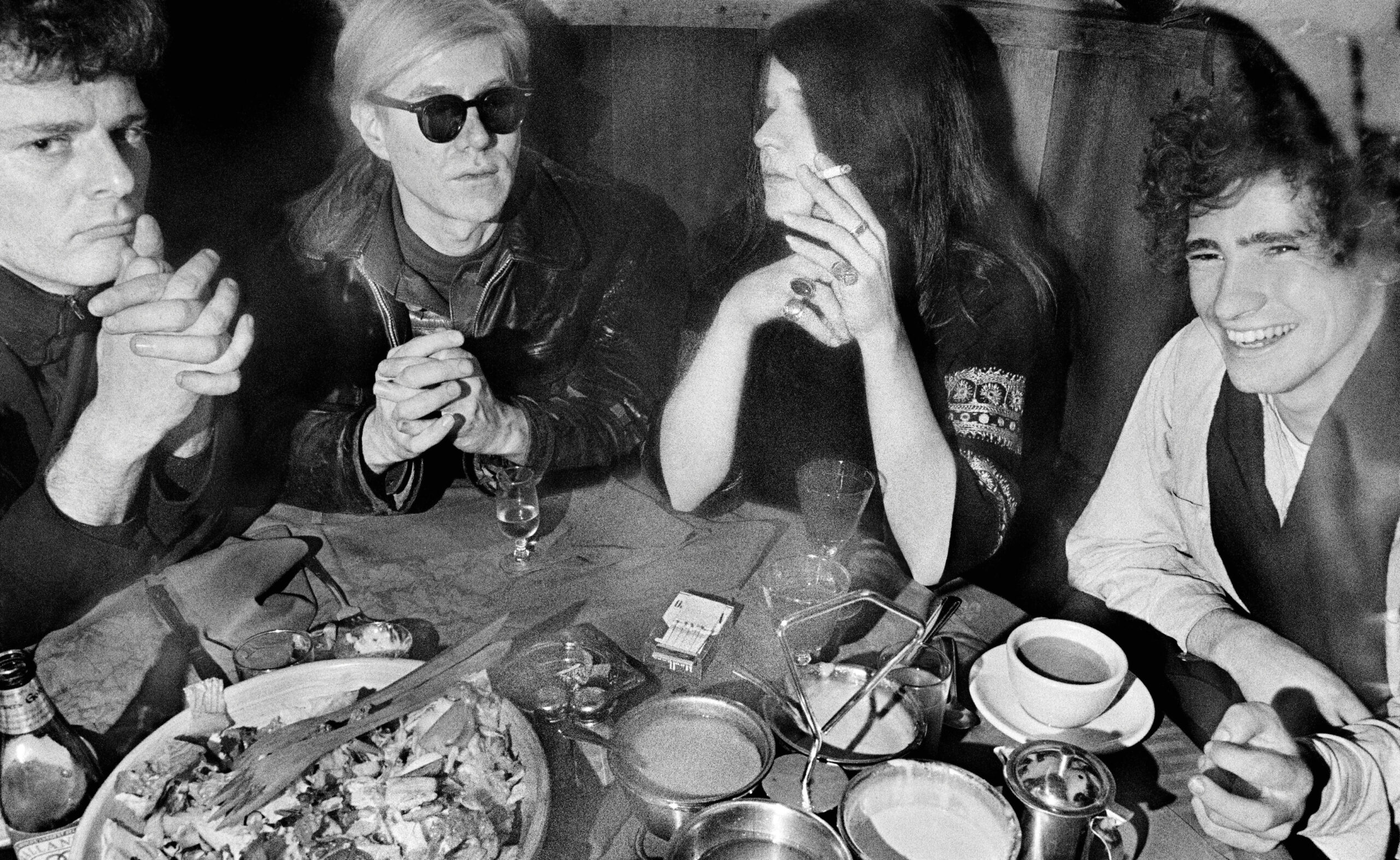

Taking it to the Max: (top, from left) film director Paul Morrissey, Andy Warhol, Janis Joplin and Buckley at Max’s Kansas City, New York, 1968.

LARRY BECKETT’S LAWYER HAD GOOD NEWS and bad news.

The positive was that, as best as Beckett remembers, he had earned $1,842 on songs he had written with Buckley, his high-school friend and bandmate. The negative, though, was that he had $1,842 in legal fees, due to the lawyer who had been working to get him out of the US Army. Beckett wasn’t too worried, though. After battling the Army for more than a year, he was finally on his way to freedom. In June 1969, after charges of being absent without leave and desertion and time spent in a stockade, Beckett was done.

When the poet settled in Portland, Oregon, with the artist he soon married, he and Buckley began catching up by phone. They talked about new songs while Buckley, still in California, sat in a recliner wearing thermal underwear and a black robe, cradling his guitar. Buckley finally decided to visit, hoping to write together for an upcoming album. Beckett’s early lovesick poetry had formed the bulk of the lyrics on Buckley’s debut, and he’d subsequently helped usher in the political and surrealistic aspects of the singer’s repertoire. Buckley, however, had written his last three albums alone, though he allegedly turned down a chance to write music for John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy since Beckett, in the Army, couldn’t help.

“We collaborated on the lyrics to a song, as though he were hesitant to have me go full-bore without him steering it,” Beckett tells MOJO from his home, still in Portland, where he has remained a poet and recently recorded an album featuring the songs of Jacques Brel. “We had no experience collaborating as writers, and it was a miserable experience. It was such a forced, sour engagement. He said, ‘Just send me the lyrics you write.’”

“Tim was always frustrated by any boundaries superimposed on his will. We were caught between the commercialisation and the improvisation of music.”

Lee Underwood

Beckett wrote four new songs for the album, including the one they’d tried to pen together – I Woke Up, an anxious and impressionistic aubade about the possibility and weight of the future. In the fall of 1970, a year after Lorca was finished, Beckett returned to California to watch his words become the songs of Starsailor. He was stunned.

“When Tim made Goodbye And Hello, he would just wander around the studio, bumping into things. He had no idea, so he was relying on the producer, Jerry Yester, to answer questions,” remembers Beckett. But this time, Buckley would sing or play something, ask to hear it back, and then offer ideas in real time about what needed to change, how the pieces could fit together. “He was in complete control. Any question he was asked, he had the answer.”

Tim kicking back in 1970.

Around the time of the session, Buckley was also penning a hilarious and acerbic editorial for The New York Times about Beethoven, full of barbs for rock musicians and fans alike. “Hardly anybody I know listens to him,” he wrote, “maybe because they can’t play him on the guitar.” Beckett and Buckley were also engrossed in the atonality of Krzysztof Penderecki, Toshiro Mayuzumi, and Berio. Beckett could now hear that here.

The work stirred Beckett so much he suggested they resurrect Song To The Siren, a song they’d struggled to get right in a plaintive folk form years earlier. Buckley harmonised with himself, his voice curling over gauzy harmonies that stretched out like galaxies. Underwood’s spare electric guitar undergirded him, rising and falling around Buckley’s swoops. Song To The Siren became Starsailor’s centrepiece and, in years to come, the calling card for Buckley’s experimental legacy. “It was like he came into possession of his muse,” Beckett says. “He was hesitant at first, and then he became stronger and stronger.”

Buckley overdubbed 16 vocal tracks, even running some of them backwards, for the title cut, a poem turned into a tape experiment. The returning Balkin and Gardner brothers darted in and out of I Woke Up and blared with Albert Ayler gusto on The Healing Festival. It was astounding, and Underwood insists, Buckley knew it. “He said, ‘That’s my best album,’” Underwood remembers. “‘That’s my major work.’”

Buckley also understood it was a tough sell. True to his word, he took his Starsailor band into jazz clubs, starting with an October 1970 date at the tiny Lion’s Share, near San Francisco. The band was savage, hammering and howling through a 12-minute rendition of Lorca and flowing in and out of eerie renditions of Starsailor. Warped vocals blew like wind from a cave. The audacious music met reserved applause.

“He would address his crowd by saying, ‘Good evening, lobos.’ That was his entourage’s slang for lobotomies,” says Beckett. “He meant these people had no brains, and they were not going to like this music. He had only contempt.”

Siren call: Buckley performing on Midnight Special with the Steve Miller Band, 1974.

WHEN BUCKLEY FINISHED TOURING STARSAILOR, he needed a break. He’d made three albums in a year, and both Lorca and Starsailor turned him into something of a punching bag. “There is an annoying problem about the album: [it] is a collection of junked tapes,” ran one former fan’s review of Lorca in a student newspaper. “The arrangement and selection of songs do not correspond with Buckley’s usual habits.”

What’s more, after swearing off the idea of a second marriage after a divorce in 1966, he had wed Judy Sutcliffe and become the stepfather to her son, Taylor, in April 1970. He wanted to try being a family man, to watch the Los Angeles Lakers, play baseball with Zappa, and take road trips with Judy. The drugs had sometimes been hard, the road gruelling, the assorted tensions among his band members exhausting. “I’d been going strong since 1966, and I really needed a rest,” he said in 1974. “I hadn’t caught up with any living.”

Buckley was always working, according to Judy, doodling lyrics on cocktail napkins or thinking about songs, even if he didn’t have his guitar. But when he properly returned to work in 1972, it was clear he had, once again, broken with his past. He’d played the role of Glen, an out-of-work drummer with family issues, in Why, a Victor Stoloff film about a fractious residential therapy session that ends with everyone caressing each other’s faces. Starring a young OJ Simpson, it was an early experiment in shooting to video tape, but it was a flop. Buckley’s character stung. “I feel like everything that I’ve done, made, or believed in has been a waste of time,” said Buckley, an onscreen natural. “I can’t live like that.”

Indeed, Buckley re-emerged willing to try his hand at something like stardom. He jettisoned his old band almost entirely, with only Collins returning on conga. He added strings, background singers, horns, and a rhythm section of session players. “After Lorca and Starsailor, I was pretty much irrelevant,” admits Underwood. “He needed to find other means, because he was constantly changing. He was deeply into pop music, and I had no connection with pop music.”

Siren call: relaxing at home with The Shangri-Las, April 12, 1967.

Greetings From L.A., Buckley’s seventh LP, was a funky, hooky affair, its seven rambunctious songs inspired by listening, he said, to the radio. But many of its tunes neared the seven-minute mark, and Buckley’s lyrics about foot fetishes and squeaking bed springs curbed its commercial appeal. “Ball and chain on the old brain!” he said in 1972 of writing songs to turn into singles. “I don’t see it as a compromise, though. It’s just part of my life having to do something like that.”

He didn’t stop, either: young producer Denny Randell scrubbed 1973’s Sefronia until it felt smooth, sounded saccharine. Look At The Fool was a major improvement, with Beckett returning to write some lyrics. Jim Fielder, the high school friend who introduced the two before joining Blood, Sweat & Tears, was in on those sessions. Despite the title and his sullen face on both covers, engineer Stan Agol insisted Buckley was finding new momentum in 1974. “His career was looking up,” Agol said in 2000. “He was leaving Herb Cohen and signing a big deal. He was not a junky!”

Onscreen natural Buckley with OJ Simpson in Victor Stoloff’s 1973 movie Why.

TIM BUCKLEY DIED ON JUNE 29, 1975, HOURS after returning to California from a short tour in Texas. He’d been drunk, snorted some heroin offered by a close friend who was also his dealer, and soon died at home. That’s when Buddy Helm stopped playing music.

Helm had met Buckley during a failed Zappa audition, not long after Greetings From L.A. was finished. The drummer was smitten by Buckley’s easygoing charm, stunned by his voice. They both adored Fred Neil, even talked about making an album with him. Their shows together were tight-rope walks, Helm remembers, dovetailing moments of terror and delight. “When he’d get going, it was like I was a jockey, like being on Secretariat,” says Helm. “And I could follow him where he wanted to go.”

Helm had been with him until the end, playing that string of Texas dates, where Buckley had been uncharacteristically pleased with the reception and reviews. The singer had been in talks to play Woody Guthrie in Bound For Glory; the offer, The New York Times later reported, would have arrived days after he died. The drummer didn’t want to deal with that kind of heartbreak again. So Buddy Helm became Russell Helm, working in the film industry and swapping his stage clothes for luxe threads. “I had to get serious,” he says, laughing. “My wife said I had to have a life with benefits. What is that?”

“Tim would address his crowd by saying, ‘Good evening, lobos.’ That was his entourage’s slang for lobotomies.”

Larry Beckett

In 1983, Judy Buckley tracked down Helm. Money wasn’t showing up from Warner Bros, and she needed help from “a suit”, as she called him. He set up a meeting with lawyers at the label, arriving in a white silk suit from Barneys, hoping to play the part of the power broker. As he neared the appointed conference room, he recognised a famous face in a mixing room – Bruce Springsteen, in Los Angeles working on songs. “We looked at each other,” Helm remembers, “and a minute later, he said: ‘Tim Buckley, Max’s Kansas City.’”

Springsteen knew the former drummer was there to meet with attorneys, so he handed him his own suit – a cutoff denim jacket, slung across his chair. “Go get ’em,” Springsteen said.

Helm walked into the room of a half-dozen attorneys, Springsteen’s denim slipped over his fancy duds. When he asked if they knew who had given him the accessory, they nodded. “They thought, ‘Oh shit, he’s crazy,’” says Helm, laughing. “I told them that, without Tim, they wouldn’t have a lot of artists. He was the one that was showing the way forward.”

They cut a deal for Judy and Taylor to get paid. It wasn’t a lot, because it rarely was with Buckley. “His life,” as his other son, Jeff, once put it, “was hell.” But 50 years after Buckley’s death, Helm’s point may be more salient than ever. Buckley epitomised the idea of the restless songwriter, or anyone for whom folk music or any tune with a seemingly simple structure is not an end point but instead an invitation to explore. This Mortal Coil reinforced that nearly a decade later, when their impressionistic and amorphous cover of Song To The Siren with Elizabeth Fraser became an indie hit.

Jeff, too, carried the lessons of Happy Sad and Starsailor into his own too-brief career. They have persevered with subsequent generations of songwriters who could be called fearless if they didn’t have such a compelling precedent in Tim Buckley. His temperamental traces show up in Bon Iver and Destroyer, Mk.gee and Ryley Walker, or anywhere someone is looking to elide preconceptions of a song and figuring out how to do it themselves, particularly with a singular voice.

Tim Buckley once told a story about meeting Leontyne Price, the pioneering opera singer who could make even the high notes sound like thunder. She saw his Starsailor band in New York and confided that she wished someone would write music like that for opera. But he hadn’t waited for someone to write that music for a folk singer. He’d just done it.

“Well, do what I did,” he quipped. “Get your own band.”

IMAGES: Ed Caraeff/Iconicimages; Nurit Wilde, Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Elliott Landy/Redferns/Getty, Ed Caraeff/Iconicimages; © 1978 Ed Thrasher mptvimages/eyevine, Elliott Landy/Magnum Photos; Ginny Winn/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Ron Tom/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images, Ed Caraeff/Iconicimages