Mojo

FEATURE

From Here To Eternity

Sixty years ago, the Grateful Dead embarked on a mission that would freak out label bosses, exasperate producers, and turn on millions to the infinite possibilities of improvised psychedelic rock. David Fricke heads back to 1960s San Francisco, and uncovers the method and madness behind the band’s wildest musical phase. “The Grateful Dead is an anarchy,” their accomplices reveal. “And that was good and bad.”

Words: David Fricke

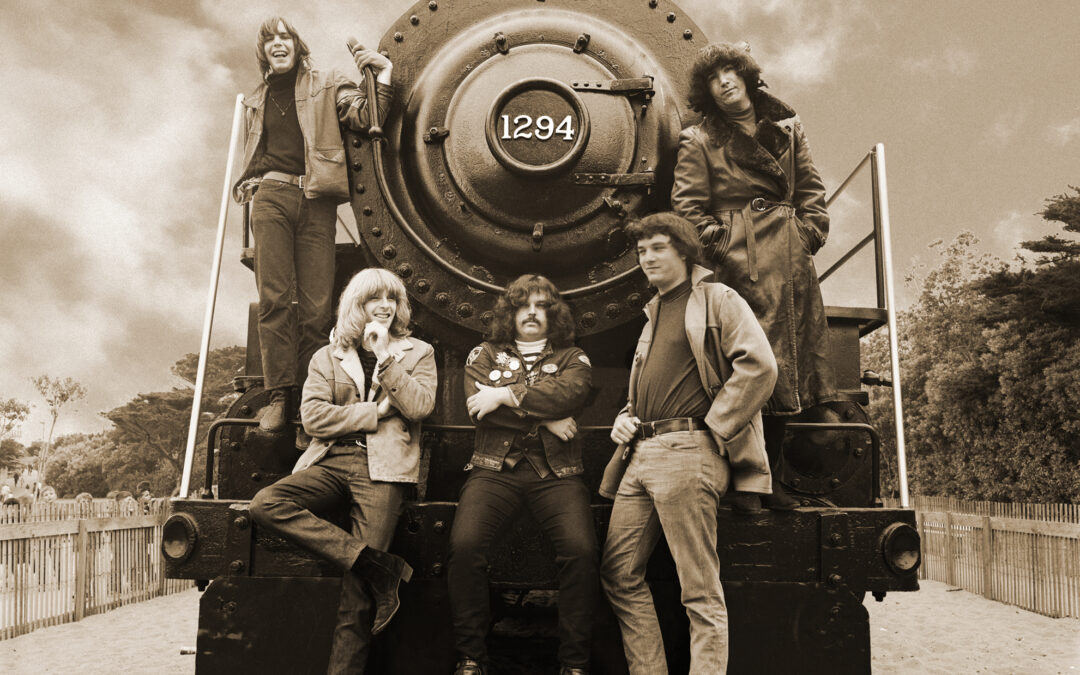

Freedom riders: the Grateful Dead get ready to steam out of San Francisco, September 1966 (from left) Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia.

THE LETTER WAS DATED December 27, 1967, on the official stationery of Warner Bros Records president Joe Smith, addressed to Danny Rifkin, co-manager of the label’s biggest investment in the San Francisco scene – the Grateful Dead. Smith was not happy.

“Lack of preparation, direction and cooperation from the very beginning have made this album the most unreasonable project with which we have ever involved ourselves,” Smith wrote of the chaos around the Dead’s second LP, less than half-done after two months at four studios in Los Angeles and New York. Producer Dave Hassinger – who’d engineered Top 5 albums by The Rolling Stones and Jefferson Airplane – had quit, fed up with the Dead’s combative manner. “Nobody in your organisation has enough influence over Phil Lesh to evoke anything resembling normal behaviour,” Smith complained to Rifkin, referring to the Dead’s cerebral, iron-willed bassist – half of the turmoil’s leading wedge with guitarist Jerry Garcia.

It was an inevitable clash of wills in a business overturned by The Beatles’ lavish milestone, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Dead’s deal with Warner Bros, signed in autumn 1966, ensured Garcia, Lesh, guitarist Bob Weir, organist Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan and drummer Bill Kreutzmann full artistic control and unlimited studio time.

Hassinger, hired for their debut album, ignored that, producing The Grateful Dead in four days. Nervous and speeding on Dexamyl, a diet medication, the Bay Area’s hottest improvising dance band zipped through a typical setlist of folk and blues covers in brittle, mostly three-minute blasts.

Aside from a 1965 demo session as the Emergency Crew and a ’66 single for an obscure local imprint, “we had no real record consciousness,” Garcia admitted to Rolling Stone in 1972. The Grateful Dead, issued in March, 1967, “was simply what we were doing on-stage,” played “way too fast… It was weird, and we realised it.”

The band’s original concept, Garcia confessed in another interview, was “unreasonable… one LP, two sides, one song” – closer to the LSD-assisted infinity the Dead sought in performance, pursuing collective transcendence in the R&B and Delta fundamentals of Wilson Pickett’s In The Midnight Hour and the Cannon’s Jug Stompers’ Viola Lee Blues. “It was a combination of mistake, fate and faith,” Weir said, looking back in 2009. “We learned to trust ourselves and each other,” while serving the audience. “Our job was to find the beat and get people dancing.”

The second album would go, as Garcia put it, “that whole other way”. In September 1967, as recording commenced in LA, the guitarist confided his plan for the Dead’s enduring portrait of the ballroom experience in San Francisco’s brief season of acid, licence and community – 1968’s Anthem Of The Sun. “We’re thinking of doing parts of the next album live,” he told jazz critic Frank Kofsky. “We’re also gonna try doing stuff with combining live and studio.” The band had “some nice, heavy material and good ideas”.

This time, Garcia warned, “We’re gonna go in and fuck around.”

Wizard gear: The Warlocks,(from left) Lesh, Weir, Kreutzmann, Garcia, McKernan, 1965

THAT’s all they did at first, accomplishing “absolutely nothing” in LA, Garcia said, then driving Hassinger around the bend in New York. “We were being so weird,” Garcia noted generously. The producer “was only human after all”.

The Dead were now a fiercely polyrhythmic force, adding a second drummer, Brooklyn-born Mickey Hart, after he met Kreutzmann at a Count Basie show, and the two locked like brothers during a Dead gig in late September 1967. This was a newly assertive band of composers too, recording entirely original material for Anthem even as it evolved in shape and detail on-stage. That’s It For The Other One was a wildly swerving multi-part suite with a churning, staccato centre inspired by The Yardbirds’ Little Games.

Garcia described New Potato Caboose to journalist Ralph J Gleason as “a very long thing” without “verse-chorus form” but plenty of “fast, difficult transitions”.

Garcia persuaded Robert Hunter, a poet friend from their teenage years in Palo Alto, to contribute lyrics. In the early 1960s, the two played folk and bluegrass in coffeehouse combos, and Hunter’s reports from his 1962 participation in an LSD-research programme at Stanford University inspired his friend to go tripping. Fittingly, Dark Star, Hunter’s first, crucial submission to the Dead, was a compact rapture in luxuriant, galactic metaphor.

Recorded as a single in New York, it immediately took on light-year dimension in live improvisations.

“What we were up to in Dark Star was the grit,” Weir claimed in 2005. “It had contour every night. We’d try to get to the same realms within the tune. But it was also different every night when we got there.” In 2014, Lesh likened the Dead in free flight to John Coltrane’s mid-’60s quartet “where they would play out on those modes, one root. But there is so much in there.”

A classically trained trumpeter who studied modern composition at Mills College in Oakland, Lesh introduced another key, disruptive element: pianist Tom Constanten, his roommate at Mills. Serving in the US Air Force, stationed in Las Vegas, Constanten took leave to join the Anthem bedlam as “an avant-garde handyman”, he says today. Constanten believes his jolts of surrealism – prepared piano, electronic tape manipulation – were “the beginning of the end” for Hassinger. “I’m proud to have contributed to that.”

The tipping point came in New York over Weir’s request for “thick air” in Born Cross-Eyed, a two-minute uproar of shifting tempos, shrieks of guitar and Lesh’s mariachi trumpet. What Weir wanted but couldn’t articulate, as he recalled in Playing In The Band, a Dead oral history, “was a little bit of white noise and compression… like the buzzing you hear in your ears on a hot, sticky summer day.” Hassinger didn’t hang around to figure it out.

The Dead were now in charge. Overdubbing and mixing went into the spring of 1968 in three more studios as Garcia, Lesh and the band’s live-sound engineer Dan Healy drew passages from three months of concert tapes for Anthem’s brash alchemy of raw craft, stage impulse and musique concrète. The Dead found time as well to reply to Joe Smith’s letter, returning it with a message scrawled sideways in big, block letters: “FUCK YOU.”

Trip advisor: Garcia in the mood on-stage at the Artists Liberation Front Festival, The Panhandle, San Francisco, October 16, 1966

PROMOTER BILL GRAHAM, a lifelong friend of the Dead, summed up their music and mission in a sign posted outside San Francisco’s Winterland when the band headlined the venue’s closing night, New Year’s Eve 1978: “They’re not the best at what they do, they’re the only ones that do what they do.”

In their 60th year, the surviving members continue to do whatever that is. After six months working in clubs as The Warlocks, the Grateful Dead played their first official show under that name at Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium on December 10, 1965. The group formally disbanded 30 years later after Garcia’s death of a heart attack, in drug rehab, in August 1995. He was 53.

The music never stopped. Just as the Dead carried on from the 1973 loss of McKernan to alcohol-related liver disease and keyboardist Brent Mydland’s fatal drug overdose in 1990, Weir, Lesh, Hart and Kreutzmann toured and recorded with separate projects and in states of reunion. Prospects for a 60th birthday event ended with Lesh’s passing in October 2024, at 84. But Weir and Hart were in Las Vegas this spring with Dead And Company, and Weir brings his group the Wolf Bros to Britain this summer.

Meanwhile, in the massive box set tradition of 2011’s Europe ’72: The Complete Recordings (73 CDs) and 2015’s 30 Trips Around The Sun (80 CDs), Enjoying The Ride – released on May 30 – is 60 discs of gigs from Deadhead shrines such as the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York, Red Rocks in Colorado and the Fillmore West. The last is represented by three nights of psychedelic prime time in June 1969, two weeks before the release of the Dead’s third album, Aoxomoxoa, a pioneering cosmic Americana as confounding in its execution as its palindromic title, coined by cover artist Rick Griffin.

That LP was nearly the end of the ride. Recording took six months and drove the Dead into perilous debt to Warner Bros. And for a couple of weeks in October 1968, Weir and McKernan were fired. “The Dead tried it without them,” says the band’s archivist and reissue producer David Lemieux. “There are studio sessions of the Dead playing with another couple of guitar players, trying things out. But it didn’t last long.”

”We learned to trust ourselves and each other. Our job was to find the beat and get people dancing.”

Bob Weir

The Grateful Dead were an improbable alliance from the start, forged in a post-Beat San Francisco of folk purism and impatient electricity, a Greenwich Village West itching to be a California Liverpool. In 1964, Garcia was a discharged Army veteran teaching guitar and banjo at a music store in Palo Alto, despite lacking two joints on his right middle finger (thanks to a woodchopping accident as a child). Weir, a teenage tearaway from a wealthy, adoptive family, and Kreutzmann, drummer in a local R&B band, frequented the store. McKernan was born to rebellion, the son of a white R&B DJ. Self-taught on piano and harmonica, he wore biker gear, as untidy as his Peanuts nickname implied. He worked at the store with Garcia; played with him and Weir in a jug band; and, in late 1964, suggested a rock group was in order.

“We got our first gigs because we were a blues-oriented Rolling Stones-style band,” Garcia said of the ensuing combo, The Warlocks. And they were something else too. The son of the music store’s owner was on bass when Lesh saw The Warlocks at Magoo’s, a Menlo Park pizza joint in May 1965. “It was the sheer, raw, exhilarating sound of it,” Lesh told me in 2014, beaming at the memory. “It was like I could swim in it… The next thing that happened was Garcia sat me down and said, ‘Hey, man, I want you to play bass in this band.’” Lesh had never played bass before.

Garcia didn’t care. They were mutually impressed on first meeting in 1962: Lesh by Garcia’s guitar prowess in the folk clubs, Garcia by Lesh’s intellect and musical curiosity. Lesh took to bass like he was doing Bach, precisely articulated notes in endless, stairstep variations on any given melody. As an electric guitarist, Garcia combined bluegrass picking with a skidding tone and sustain that evoked his pedal-steel guitar idol Ralph Mooney from Buck Owens’ Buckaroos. Peter Grant, who played pedal steel on Aoxomoxoa, had banjo lessons from Garcia in 1964. “He was showing me pedal-steel stuff on banjo,” Grant says. “And listen to Beat It On Down The Line [on The Grateful Dead]. The first three-quarters of the solo is like a pedal-steel break.”

Never just a rhythm guitarist, Weir was a moving, elliptical factor “inbetween the lead and the bass”, as he described it, “intuiting where the hell they’re gonna go and being there.” Kreutzmann was “the rhythm of the earth,” Hart told Rolling Stone in 1969. “Bill feeds that to me, I play off it, and he responds. When we’re into it, it’s like a drummer with two minds, eight arms and one soul.”

McKernan was the Dead’s blues conscience, the original frontman on vocals and a “sweet, mellow guy,” according to Lesh, “except when he was up there, honking into that microphone.” McKernan’s death at 27 profoundly affected Garcia. “Jerry was a little intimidated,” Lesh said, “because he knew he had to be the guy now. And that was never his trip. He never wanted to be the guy. It devolved upon him.”

Beat generation: the Dead enjoy a Panhandle hang in 1967 (from left) Mickey Hart, Lesh, Weir, Kreutzmann, McKernan, Garcia.

DAN HEALY was a young engineer at a studio specialising in advertising jingles, living in a houseboat on San Francisco Bay next to Quicksilver Messenger Service, when he saw the Dead for the first time at the Fillmore in the summer of 1966. It was a lucky break for the Dead, on a bill with Quicksilver. Lesh suffered a fried amplifier during the set; Healy got it working. “John ratted me out,” Healy says, laughing, of Quicksilver guitarist John Cipollina. “None of the bands had any money to buy strings or take an amp to a repair shop. I knew how to fix stuff.”

Healy was not impressed by the din coming through the PA. “I was accustomed to the studio, having control over the sound,” he explains. “Pigpen’s singing – I couldn’t understand a word. He was this gurgling noise.” Healy had an epiphany: “Recreate the studio on an audience-wide scale so everybody could hear the music.” That became “a life-long trip”. The Dead had parted with Augustus Owsley Stanley III AKA ‘Bear’, their first soundman and main source of top-shelf LSD. Healy got on the desk, serving in different eras into the 1990s.

Anthem Of The Sun was his trial by fire. Effectively banned from any sensible recording facility in LA or New York, Healy and the Dead went into Columbus Recorders, a San Francisco space, with the unfinished 8-track master of side one and “no music for side two”, Healy says. “They didn’t have songs to record.” To make up the difference, Healy took a 4-track stereo recorder on the Dead’s winter ’68 road trip up to the Pacific Northwest, back home for Valentine’s Day at the Carousel Ballroom and to Lake Tahoe for a stand at King’s Beach Bowl, a bowling alley. From that stash came the guts of a side two blur combining Alligator, a comic blues with Hunter-McKernan lyrics, and the chugging minimalism of Caution (Do Not Stop On Tracks), one of the Emergency Crew demos.

The origin of the latter depends on the teller. Weir remembered hearing Them’s 1965 pneumatic-blues single Mystic Eyes on the radio and a group exclamation: “Check this out! We can do this!” In his 2005 memoir, Lesh described a train ride to gigs in Vancouver in July 1966, he and Kreutzmann “entranced by the rhythm of the wheels clickety-clacking over the welds in the rails.” “Caution,” Lesh wrote, was “one of our simplest yet farthest reaching musical explorations… one chord… played at a blistering tempo.”

Both accounts, it seems, are true. The demo was a virtual Xerox of Them’s record. But in concert across ’66 and ’67, Caution took off like a ride without end, paired with Alligator in a remarkable prophecy of Krautrock pulse and ’70s Afrobeat with blues-band fury and McKernan’s hobo-shaman singing. The title, from the signs at railroad crossings, was deliberate. “Caution,” Weir noted, “was anything but what the tune was about.”

“It was mostly a group of hippies doin’ their thing. We thought of ourselves as brats that got into a studio, trying everything.”

David Nelson

The prevailing mystery of Anthem is what came from where. “They kept building on this master 8-track recording,” Lemieux says. “They brought that to different studios and added to it” – the call-response of fuzz guitar and kazoos in Alligator; the eerie, underwater treatment of Garcia’s vocal in the martyr’s ballad Cryptical Envelopment, rigged by Healy with the Leslie speaker from a Hammond organ. The King’s Beach tapes “were heavily relied upon” for Alligator and Caution, Lemieux notes. “But you can hear things from the Carousel” such as McKernan’s exhortation as the drums roll in Alligator: “Come on everybody, get up and dance, it won’t ruin ya!”

“We were assembling a stained-glass window,” Constanten observes, a dogged, piecemeal approach documented in an extraordinary artefact: Lesh’s hand-written mix breakdown on yellow legal-tablet paper of everything over each LP side on the master tape. There are sketchy references to source material, but one notation for The Other One confirms excerpts from King’s Beach, a show in Eureka, California and two nights in Portland, Oregon spread across the eight tracks at the same moment. For the edits, Healy often held his thumb on the tape machine’s flywheel to get live reels from different gigs in sync, at matching speed.

“I’ve always felt it was Phil’s idea,” Healy says of Anthem, “the concept of something that was completely ethereal, not contrived, like a walk through the forest. And nobody objected to it. You have to remember – the Grateful Dead is an anarchy. There weren’t any bosses. And that was good and bad.”

Released as a 45 in April, 1968 with a classy picture sleeve, Dark Star went right into a black hole, reportedly selling only 500 copies, although Constanten says he heard it on the radio in Las Vegas while he was finishing his Air Force time. Dark Star was not included on Anthem Of The Sun because, Lesh said in 1984, “It just moved too fast.” Hunter made a spoken cameo at the end, reciting a passage about spinning stars and “waxen wind”. And Garcia is heard on banjo, from an old tape of a lesson “I was giving somebody in ’62 or so,” he told the British journal Swing 51. “I threw it on the end of Dark Star just for the hell of it.”

Truckin’ on home: (main) Weir, Garcia and Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady at Newport Pop Festival, Orange County Fairgrounds, Costa Mesa, August 4, 1968.

ANOTHER LETTER landed in the Grateful Dead’s mailbox in February 1969, this time on the letterhead of Hugh Hefner, editor and publisher of Playboy. In January, the band taped an appearance for Playboy After Dark, a TV series hosted by Hefner and shot like an exclusive cocktail party. The seven-piece Dead, looking like they came from a hold-up in Tijuana, played two songs from the unfinished Aoxomoxoa: Mountains Of The Moon, a delicate ballad with prominent harpsichord flourishes by Constanten, and a roaring St Stephen, McKernan as a third drummer on congas. As credits rolled, McKernan belted his party piece, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland’s Turn On Your Lovelight. In his note, Hefner thanked the Dead “for having made the taping session as enjoyable to do as I think it will be to watch,” alluding to an extra production touch. The Dead’s crew dosed some of the libations with LSD, including Hefner’s Pepsi.

In 1972, when asked by Rolling Stone to define psychedelic music, Garcia replied by quoting Lesh: “Acid rock is music you listen to when you’re high on acid.” Aoxomoxoa was made on different fuel. “We were sipping STP during our session,” Garcia revealed, “which made it a little weird – in fact, very weird.” Also present: a four-foot-tall tank of nitrous oxide with “eight hoses coming off of it,” says Doug McKechnie, an electronic composer who operated the Moog synthesizer used on Aoxomoxoa’s crowning indulgence, What’s Become Of The Baby.

“They call it ‘laughing gas’ for a reason,” McKechnie points out cheerfully, “because everything is amusing, then thoughtful. But people would black out. I was seeing pluses and minuses and going, Oh, that’s what it all means, then hitting the floor.” One Aoxomoxoa experiment under the influence, Barbed Wire Whipping Party, was a torrent of sounds and chatter that even Garcia called “total gibberish”. It remains unreleased but available for testing on YouTube.

If Anthem Of The Sun was Lesh’s pursuit of the ideal Dead on vinyl, Aoxomoxoa was Garcia’s white whale, almost to the exclusion of the band itself. In a November 1968 story headlined “Has Frisco Gone Commercial?”, the New York Times cited “the expected fragmenting of the Grateful Dead”, Weir and McKernan “staying behind while the others move deeper into electronics.” It was a momentary breach. Weir is seen in studio photos from Aoxomoxoa, playing guitar. But Rolling Stone’s rave review in July 1969 harshly judged McKernan’s diminished role on the record: the Dead were “more magical” and “less definable without him”. On the back cover, McKernan was credited as “Pigpen”. Constanten played all keyboards.

At the centre of it all was Garcia’s voice: fragile and hermetic in the ballad miniature Rosemary and the starlit suspense of Mountains Of The Moon; brighter and stronger, ringed in harmonies, for St Stephen and China Cat Sunflower; bereft and a cappella, swimming through dark Moog rapids, in What’s Become Of The Baby. Stripped of its science, the song was a medieval lament, an epitaph for the fading utopia in the Dead’s hometown.

“It was always live,” McKechnie says of Garcia’s vocal in that bleak piece, processed as he sang by McKechnie with filters in the Moog, serial number 4 in Robert Moog’s first line of synthesizers. “The analogy is it’s the inside of your mouth, and the controls are your tongue. Once it was recorded, it was possible to run it through various things. I don’t remember,” he admits. “There was a lot of substances involved.”

“I always like to think of Grateful Dead music as electric chamber music, the music of friends.”

Phil Lesh

Garcia and Hunter wrote the eight songs on Aoxomoxoa (with Lesh for St Stephen) – “Some new runes,” as the guitarist told Rolling Stone, “that I hadn’t really bothered to teach anyone in the band.” Aoxomoxoa was done largely in overdubs. “We didn’t go about it as a group at all.” And it was recorded twice: on 8-track tape (with a working title, Earthquake Country) to the end of 1968, then on 16-track when Pacific Recording in San Mateo got an Ampex machine in that brand new format. Eight-track work was scrapped; Garcia chose to start again.

“We would look to Jerry for what he wanted, the ideas he had,” says guitarist David Nelson, an old friend and bandmate of Garcia from their bluegrass days. Nelson played “background guitar” on Rosemary, Mountains Of The Moon and Doin’ That Rag and was in the Fillmore-Beach Boys choir for China Cat Sunflower. By the summer of 1969, Nelson, singer-guitarist John ‘Marmaduke’ Dawson (another LP guest) and Garcia, on pedal steel guitar, were gigging as psychedelic cowboys the New Riders Of The Purple Sage.

“It was mostly a group of hippies,” Nelson says of Aoxomoxoa, “doin’ their thing, delighted with this new multi-track recording. We thought of ourselves as brats that got into a studio, trying everything.”

But Garcia was attentive to detail. Peter Grant says Garcia sent him a tape of Doin’ That Rag to learn the tune before going to San Mateo to tape his pedal steel part. With its sliding time and jaunty chord changes, Grant says, “It was the most complex song I’d ever played.” Recording went fine. Then Garcia called two days later. “He says, ‘Pete, you gotta come and do it again. Your part was a half-fret off.’”

Aoxomoxoa was barely underway the second time when engineers Bob Matthews and Betty Cantor-Jackson carted that 16-track Ampex from San Mateo to San Francisco to capture the Dead live at the Avalon Ballroom. “We hauled it up the back stairs,” says Cantor-Jackson, one of the most revered engineers in the Dead’s history for the clarity and force of her ‘Betty Boards’ in the 1970s. “We got a dynamic microphone into each track on the tape machine – no board, no nothing.” With more recordings a month later from the Fillmore West, Matthews and Cantor-Jackson compiled two LPs of material for the band’s appraisal. “Everybody had something to say,” she recalls. “But it was pretty much agreed about certain performances.”

Issued in November, 1969, only five months after Aoxomoxoa, Live/Dead sold well, lightening the balance sheet at Warner Bros. Recreating the era’s nightly cycle – from the winding sublime of Dark Star, into the mystic with St Stephen and its whirlwind-rhythm twin The Eleven, then to McKernan at his salacious best in Lovelight – the album was everything the Dead wanted to bottle on the previous LPs, the unpredictable soaring and sharing with the listener and each other, without the artifice and constraint of the studio. “I always liked to think of Grateful Dead music as electric chamber music,” Lesh said in 2014, “the music of friends.”

Live/Dead was also the end of a songbook. “We got so out there,” Weir reflected in 2005, “we were pushing the limits of the patience of our audience, at a time when what was becoming popular was Crosby, Stills And Nash – people who had tunes to offer. We could all sing,” he added. “But we needed songs.”

By February 1970, three months after Live/Dead came out, the band was in Pacific High Recording – practically a home studio, located a few blocks from the Fillmore West – making its next album, Workingman’s Dead. The Dead finished it in less than two weeks.

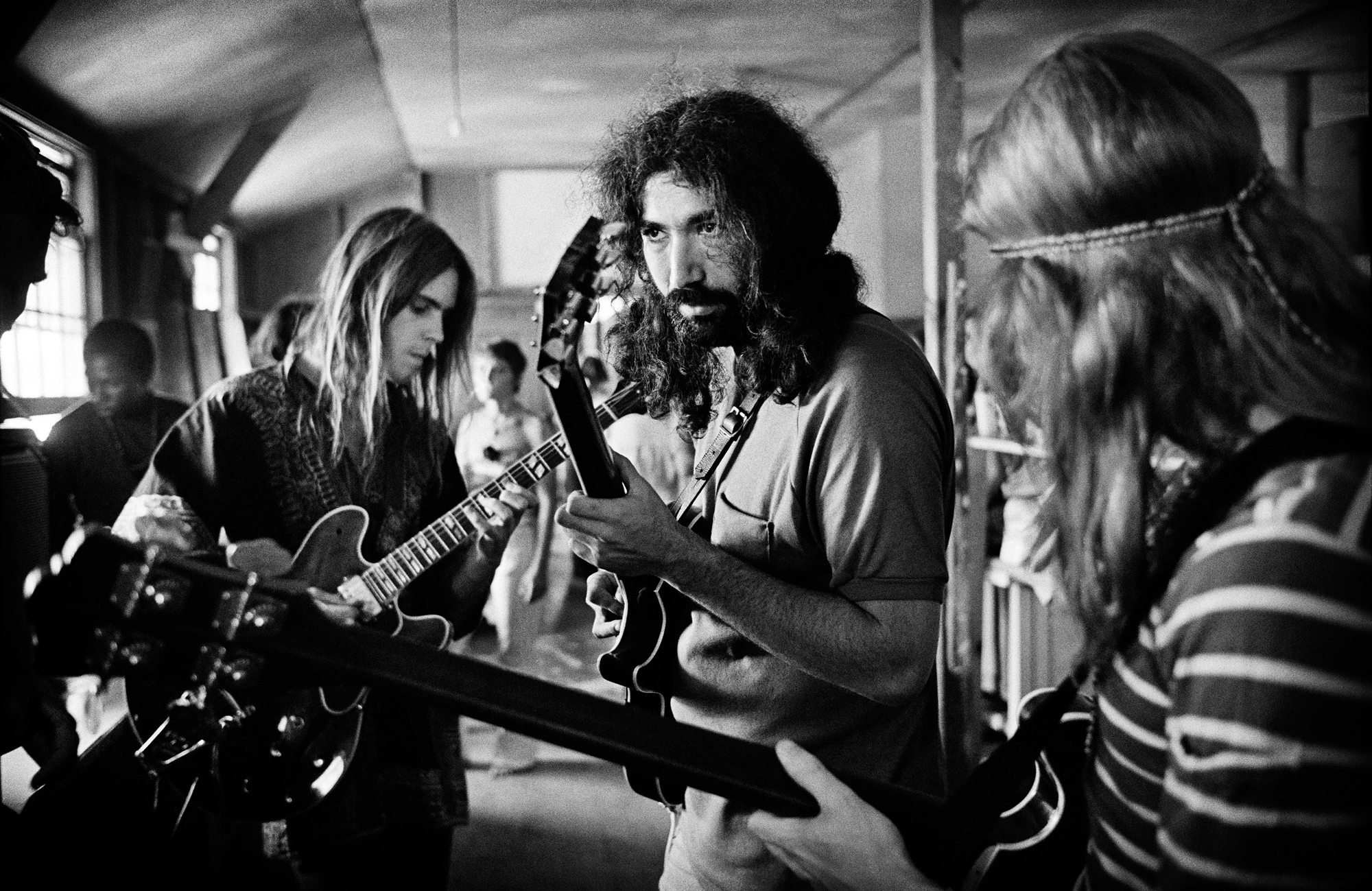

Knuckling down to make The Grateful Dead with producer Dave Hassinger, RCA Studios, LA, January 1967.

SUNRISE ON Saturday, December 6, 1969, arrived on a long, beatific note: a 20-minute drone played by McKechnie on the Moog for the multitude already gathered at Altamont Speedway, east of San Francisco, for a free festival headlined by The Rolling Stones. McKechnie brought the Moog along when he was asked to help set up the sound system. The rest of the day went south, fast: a disaster of organisation and rock-god ego with a murder in front of the Stones as they performed. The Dead – whose management worked with the Stones on the fateful issue of security by the Hell’s Angels – didn’t play, leaving as the violence escalated.

“Altamont was a wound on our culture,” says Cantor-Jackson, who worked the stage that day and recorded the Stones. “It was the first gathering of that many people in our city” – estimated at 300,000 – “and somebody died.” Two weeks later, on December 20 at the Fillmore Auditorium, near the end of the second set, the Dead debuted a song named after the field of battle, New Speedway Boogie, destined for Workingman’s Dead. Garcia sang Hunter’s prayer in the chorus with uneasy optimism: “One way or another/This darkness got to give.” Surrender was not an option.

The “long, strange trip” immortalised on 1970’s American Beauty, in the road memoir Truckin’, had a quarter-century to run for Garcia. It is still going on for those he left behind, in and beyond the band. The Grateful Dead never made another studio album in the ballroom-daze image of Anthem Of The Sun or the insular, cryptic spirit of Aoxomoxoa. There was no need. “We developed the engine, which generated a lot of energy,” Weir said of the ferment that peaked on Live/Dead. “Then we started working on ways to focus it, without trying to focus it to death.”

“It was like a dialectic,” Lesh suggested to me in 2014. “Anthem Of The Sun was the thesis. Workingman’s Dead was the antithesis”– folk- and country-rooted meditations on a counter-culture under siege but not to be denied. “Everything that came after that was a kind of synthesis of those, in varying degrees.”

Garcia retained a fondness for Aoxomoxoa, remixing the album for a 1971 re-release. “There are certain feelings and a certain kind of looseness that I dig,” he said in ’72. “It was when Hunter and I were both being more or less obscure… a lot of levels on the verbal plane.” The result was “too far out for most people”. Lesh remixed Anthem Of The Sun for a ’71 reissue but later called it “a mistake”. The original mix “is a work of art”.

Dan Healy agrees. “Stoned on acid,” the engineer says, Anthem Of The Sun “makes perfect sense.” More important, he insists, was “the concept, the stretch out, breaking that record company regimental mould. I can’t tell you how many people said, ‘You guys are gonna crash. You’ve just blown your whole thing.’

“And we said, Fuck, we can do this. And we did do it.”

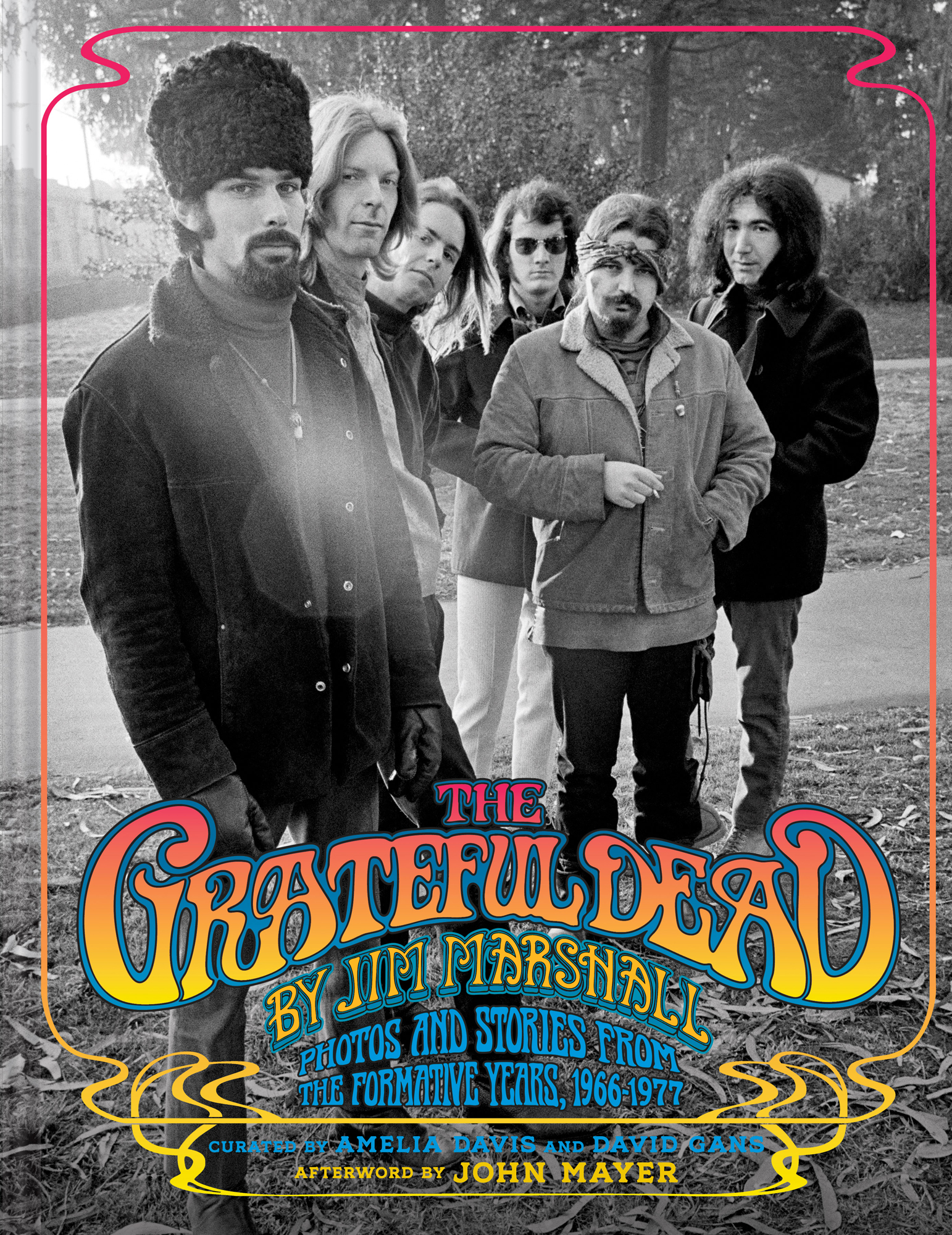

The Jim Marshall photos are taken from The Grateful Dead by Jim Marshall, published by Chronicle Books on August 5, 2025, and available from all good bookshops.