THE ROAD WARRIOR

1975 was JONI MITCHELL’s roller-coaster year: 12 months of romance and heartbreak, adventure and retreat, cocaine and Rolling Thunder. And in the middle of it, The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, her doubling-down on jazz rhythms, exotic melodies and songwriting-as-literature, with (for now, at least) a simpatico crew in tow. “It was just a good vibe,” they tell GRAYSON HAVER CURRIN. “And Joni was at the centre of it, at the peak of her powers.”

Photography by CHARLES W. BUSH

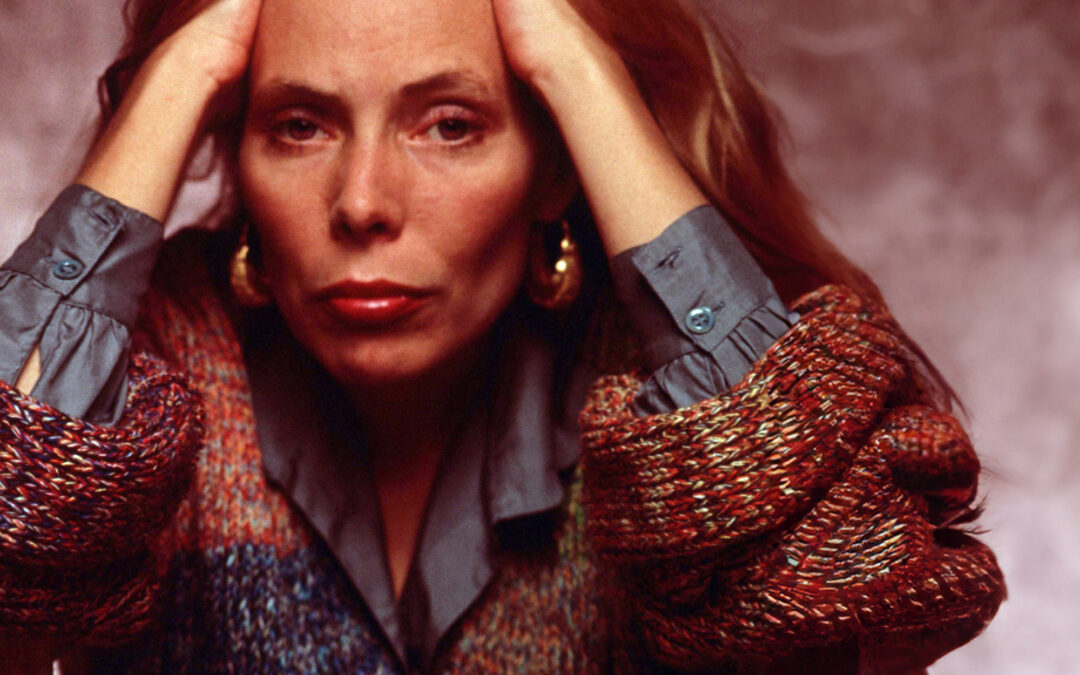

The grass is singing: Joni Mitchell, November 1975.

JONI MITCHELL NEEDED TO GET OFF-STAGE IMMEDIATELY. By late February 1976, she was two dozen dates into a 30-show tour with the L.A. Express, the band of California aces who had helped her cut The Hissing Of Summer Lawns. The plan was to wrap a Stateside run on Leap Day, take a month off, and jet from Japan to Australia to Europe for more shows. But Mitchell wasn’t even going to make it through the start of this one, as 14,000 listeners waited in the University of Maryland’s basketball arena.

As they’d done most nights, the band began with Help Me from Court And Spark, Mitchell’s voice swan-diving above Robben Ford’s ragged electric tone. Halfway through the tune, she put down her guitar – “impossible to hear,” read an outraged account in the university’s newspaper – and stalked off the stage as the band slunk toward awkward silence. Word soon came that Mitchell was sick, that the show was cancelled, and that $7.50 refunds would be available. Mitchell was in the bathroom, crying and vomiting.

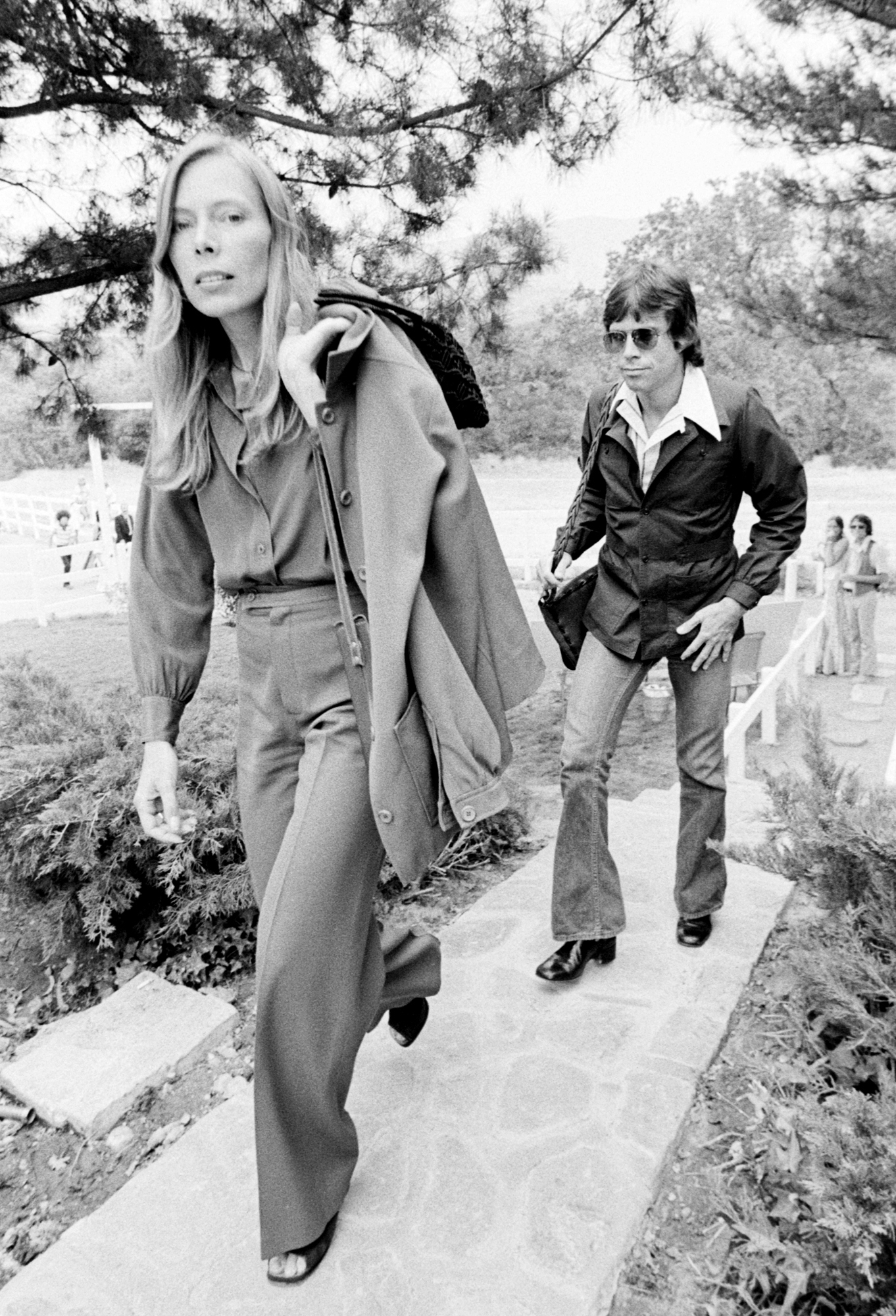

Stormy weather: Mitchell with L.A. Express drummer John Guerin, July 13, 1974

“She’s had the flu for the last two or three days,” her co-manager Ron Stone told the Washington Post, attributing the cancellation to a nationwide flu epidemic. “She probably shouldn’t have gone at all.”

Mitchell was sick. Three days earlier, after a set in Boston, she’d asked that the plane leave when the gig was done, so she could convalesce all day in New York before the next day’s sold-out show at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island. But the source was less national outbreak than personal heartbreak. Since the L.A. Express had become her band, Mitchell had been in a turbocharged relationship with its drummer, John Guerin, a strong-jawed jazz obsessive with bright eyes and a prodigious sex drive.

They’d broken up and reunited a half-dozen times before Guerin became jealous of Mitchell’s potential relationship with Bob Dylan, her road buddy for 1975’s cocaine-fuelled Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan stopped by their show in Austin, Texas, for the encore. Guerin cheated. They fought. When he told Mitchell he wanted to bring an ex-girlfriend, Judy, on tour, she agreed, so long as she stayed out of limos, planes and gigs. She didn’t. “In the next town, I got sick,” Mitchell eventually told her biographer David Yaffe. “I got the flu from the stress.”

Three years later, Mitchell confessed to Cameron Crowe that she still regretted that night, leaving so many people disappointed. The venue was a Quonset hut of bad acoustics, she said, and she was already reeling. “If I listed for you the strikes that were against me that night, I think that you could dig it,” she said before enumerating bronchitis, back aches, and lingering Rolling Thunder fatigue. “I was in physical pain. I was in emotional pain. I was going with someone in the band, and we were in the process of splitting up.”

Five shows later, the tour ended, Mitchell and the L.A. Express limping toward barbaric reviews at the Wisconsin finale. In three weeks, the inevitable announcement arrived: those international dates weren’t happening. “The decision was taken for medical reasons,” read the notice in Record Mirror & Disc. “Doctors who treated her for exhaustion and flu during her recent American tour advised her to cancel.”

That decision became one of the defining moments of Mitchell’s career. Rather than fly overseas and continue the tumult, she took a long, discursive road trip across the United States. She cloaked her stardom in pseudonyms and wigs, tucked her guitar into a used white Mercedes she bought on the road, and began writing about her heart again. The exit ultimately allowed her to make another confessional masterpiece, Hejira, while expanding on the experimental sounds with the jazz players of her recent records. She abandoned Joni Mitchell The Folk Singer on the highway.

“The journey back was one of detoxing basically from Rolling Thunder,” she once said. “That whole album was written coming out of the fog and having been really delivered from the fog into a state of absolute mental health.”

Mitchell on-stage, 1974

“I WOKE UP ONE DAY,” MITCHELL TOLD A LOS ANGELES audience in March 1974, “and I said, I can’t be having fun in this city. I gotta be supporting something, growing a garden.”

After she finished Blue in 1971, Mitchell stumbled into a Hollywood hangover, years of public relationships, music-industry manoeuvring, and international escapades having worn her down. She wanted to reset in the woods. “So I went up to Canada and picked out a piece of land, which looked to be pretty self-sufficient,” she continued, “and also had enough chromatic changes and scales in the atmosphere to keep me from going stark-raving mad.”

Mitchell wrote most of For The Roses there, reflecting on the surrealism of stardom as if she could see it fully for the first time from afar. To record it, Mitchell returned to LA, to A&M studios and a familiar producer, Henry Lewy. During the sessions, Lewy asked Tom Scott, a young saxophonist with his own quartet and credits on more than 100 records, to stop by so Mitchell could hear his take on her song Woodstock. She told him to stick around.

“I was in physical pain. I was in emotional pain. I was going with someone in the band, and we were in the process of splitting up.”

Joni Mitchell

“I absolutely couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” Scott remembered in 1974. “I knew she was a heavyweight whose music was far beyond any so-called folk-rock person I’d ever heard. And we found we worked together really well.”

Scott harmonised with Mitchell’s guitar on Barangrill and slipped dramatically into the spaces of the finale, Judgement Of The Moon And Stars. Still, For The Roses was transitional, a half-step away from her acoustic start. Mitchell was living mostly with agent-manager and Asylum Records boss David Geffen in a Hollywood mansion, after her bitter break-up with Jackson Browne led to a suicide attempt. At Geffen’s, she began working on songs for her sixth album.

With Lewy behind the boards, she cut demos in the summer of 1973, chaining four new tunes in a 13-minute piano medley and slipping through the melodic switchbacks of Just Like This Train on guitar. Drummer Russ Kunkel, who had played with Mitchell since Blue, bowed out; she needed a new band, he said, a jazz unit comfortable with her burgeoning rhythmic complications. (Neil Young and his Santa Monica Flyers gave it a roughshod try later that summer during the Tonight’s The Night sessions.)

Scott had invited her to see L.A. Express, his new band with Larry Carlton on guitar, Joe Sample on keyboards, and a deal with Lou Adler’s Ode Records. They were regulars at the Baked Potato, a funky-looking jazz club in Studio City. “Very timidly, she asked if the guys might be interested in playing on a few tracks on her new album,” Scott told Rolling Stone. By the autumn of 1973, they were all in A&M, the L.A. Express delivering soft, athletic jazz reinforcement. “As it turned out, we did the whole album.”

That album, Court And Spark, arrived via Asylum in January 1974; by that summer, Mitchell had her only Top 10 hit, Help Me.

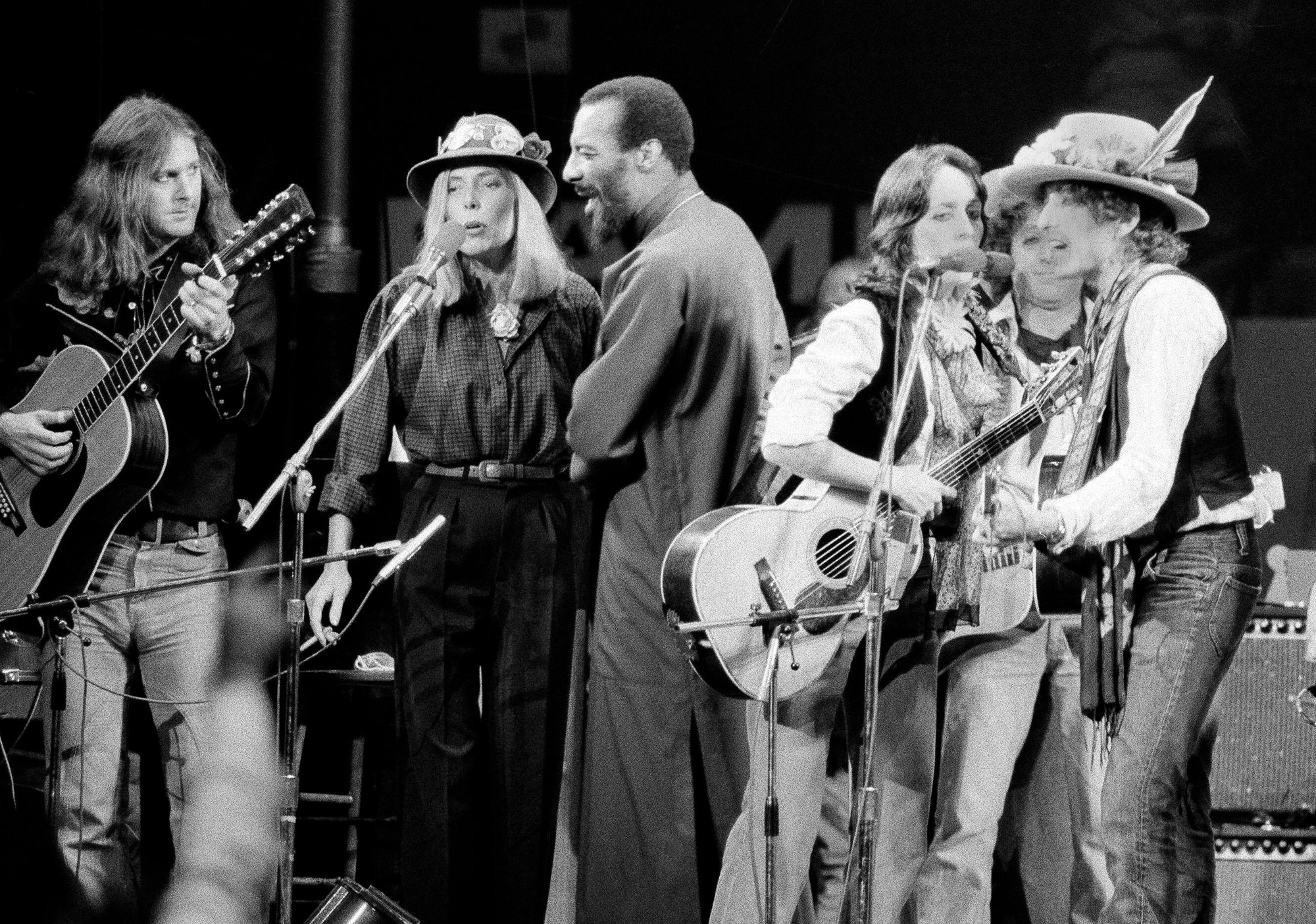

The Rolling Thunder Revue finale, Madison Square Garden, December 8, 1975 (from left) Roger McGuinn, Mitchell, Richie Havens, Joan Baez, Ramblin‘ Jack Elliott, Bob Dylan.

THE DAY THAT ROBBEN FORD’S invitation to join Mitchell’s band arrived was the very day he’d intended to start his own.

Raised in a small Northern California town, Ford, then 22, had been touring with Jimmy Witherspoon after the blues singer heard the young guitarist’s group open for him. “I was like, Holy shit, I’m playing with one of my heroes, this blues legend,” Ford tells MOJO. “But after two years, I was really ready to move on with my music. I was just an idiot, a punk kid.”

But as he waited for ’Spoon in a Los Angeles office to break the news, the phone rang. It was Scott, the L.A. Express saxophonist and bandleader, calling with an offer: did Ford want to tour with Joni Mitchell? Ford turned him down, but Scott persisted, telling him to listen to acetates of Court And Spark and Tom Scott & The L.A. Express. In a big John Coltrane phase, Ford didn’t love the latter, but the former caught his ear and imagination, particularly Guerin’s subtle but steady drumming. Scott invited him to jam with the band the next day at A&M, to see if it clicked. When it did, Scott bluffed, telling Ford other guitarists were on their way to the audition. If he wanted the job, he’d better take it.

“There was a bunch of money involved, but I didn’t know much about money,” Ford says. “The deciding factor was that I was going to be around all these great musicians. I could learn a lot.”

In full bloom: Joni Mitchell enjoys her garden life

Scott took Ford shopping for a new guitar, amplifier, and starter pack of pedals that would mirror what Larry Carlton had played on Court And Spark. (“That was instant,” Carlton tells MOJO of his and Joe Sample’s decision not to tour. “We were still very busy in the studio, and I knew it wasn’t the right thing.”) After two weeks of rehearsals in Hollywood, they were off for a three-month tour of civic centres, opera halls, and even a high-school auditorium.

Nearly a decade had passed since Dylan went electric, and popular ideas of pure folk had eroded. Still, Mitchell and the Express encountered qualms. When someone in Chicago yelled for Mitchell to turn down the volume, she quipped, “What’s the matter, do we have a hall full of purists? I thought Chicago liked to boogie.”

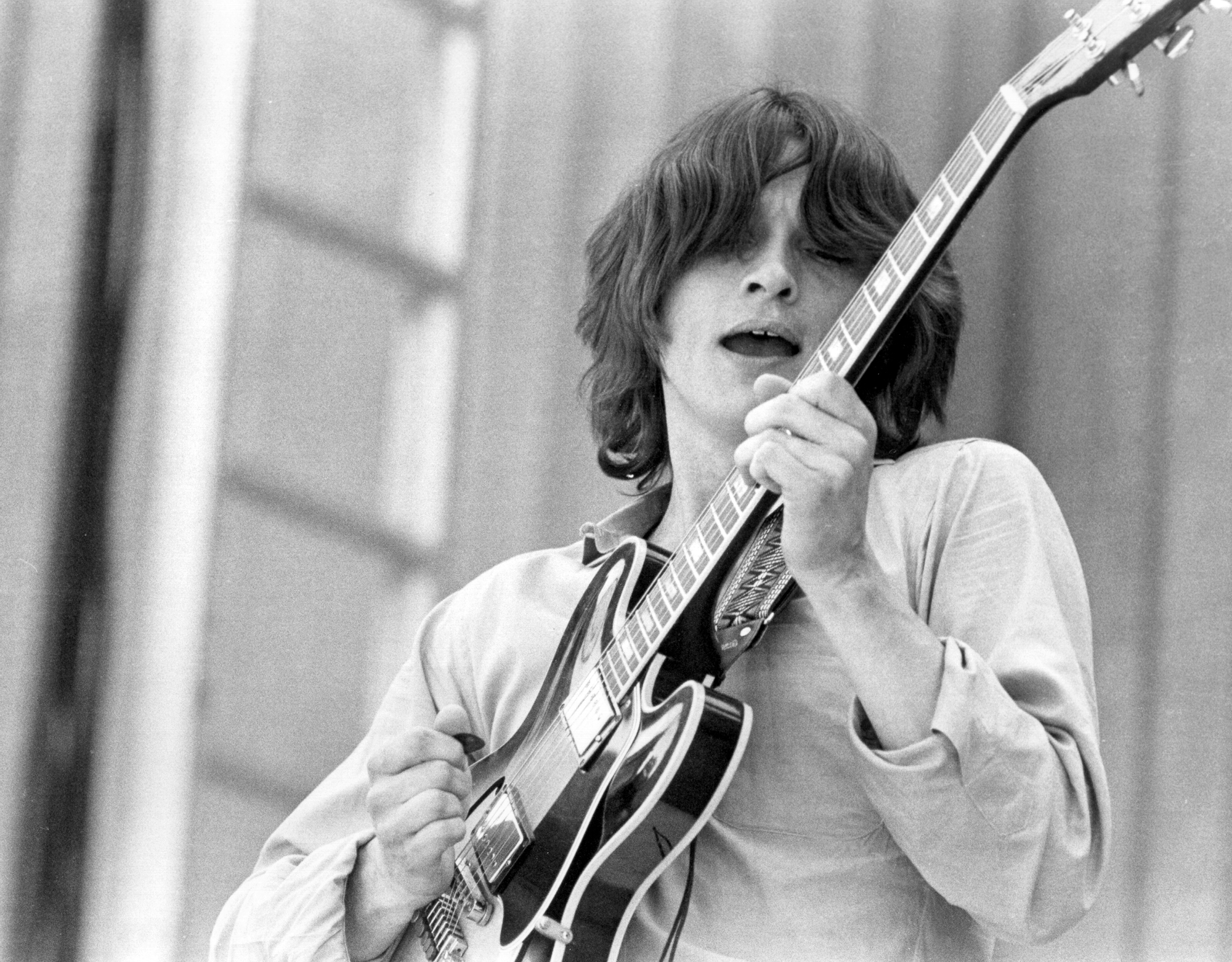

L.A. Express guitarist Robben Ford

Camaraderie quickly emerged. Ford remembers it all seemed like family, driving from show to show in a crowded Winnebago. “It never felt like, Oh, this is a drag. It was just a good vibe,” he says. “And Joni was just at the centre of it, at the peak of her powers.”

Ford even lived with Scott during the three-month break between winter and summer tours. When they returned to the road in July, they headed for bigger stages with a new keyboardist, Larry Nash. Two weeks into the run, they played five nights at Los Angeles’ Universal Amphitheatre, selling 26,000 tickets.

Mitchell with her co-manager Elliot Roberts taking care of business, Amsterdam, 1972.

On opening night, on top of a gown and heels, Mitchell wore a denim jacket borrowed from a stagehand. “Once a coffee-house folk-singer void of make-up and polish, she has molded a new image around her splendid mystery,” wrote Frank Suraci in the Los Angeles Times. “Scattered pleas for songs from the past filled the air Tuesday, but Miss Mitchell virtually ignored them, comparing the oldies to ‘an old dress I outgrew’.”

Those shows became the core of Miles Of Aisles, released that November. Mirroring the sets themselves, Mitchell was solo in the live double-album’s centre, strumming the dulcimer on All I Want and floating above piano clouds during Real Good For Free. Scott howled with his saxophone to close a funky Woodstock, though, while Ford’s electric guitar slashed through Carey in neon waves.

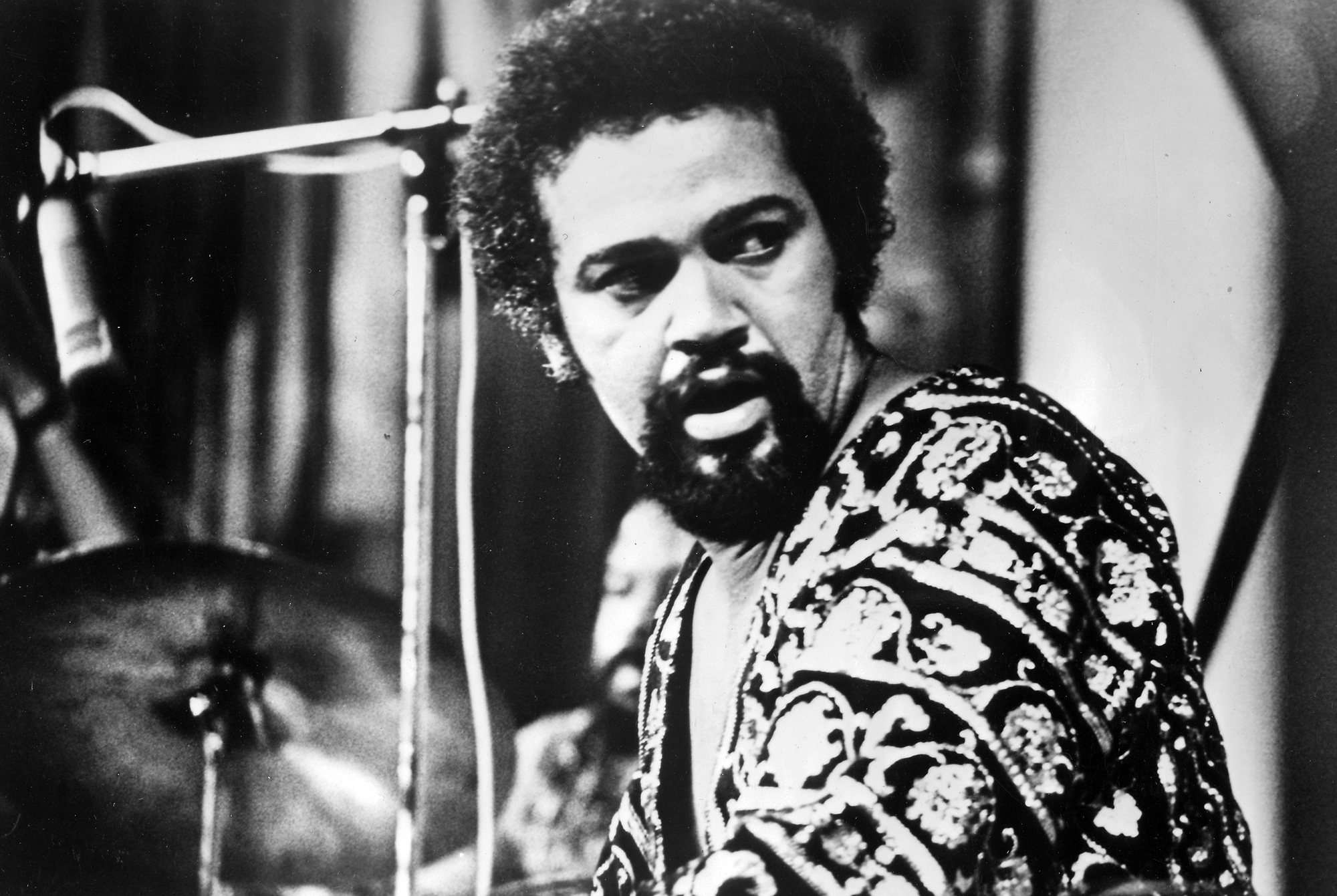

Joe Sample, L.A. Express keyboardist, 1977

“Nobody ever said to Van Gogh, ‘Paint a Starry Night again, man,’” Mitchell said, responding to requests and laughing huskily. “He painted it. That was it. Let’s sing this song together, OK?”

She played The Circle Game, an old tune about ageing and trying to move on, hard as it may be.

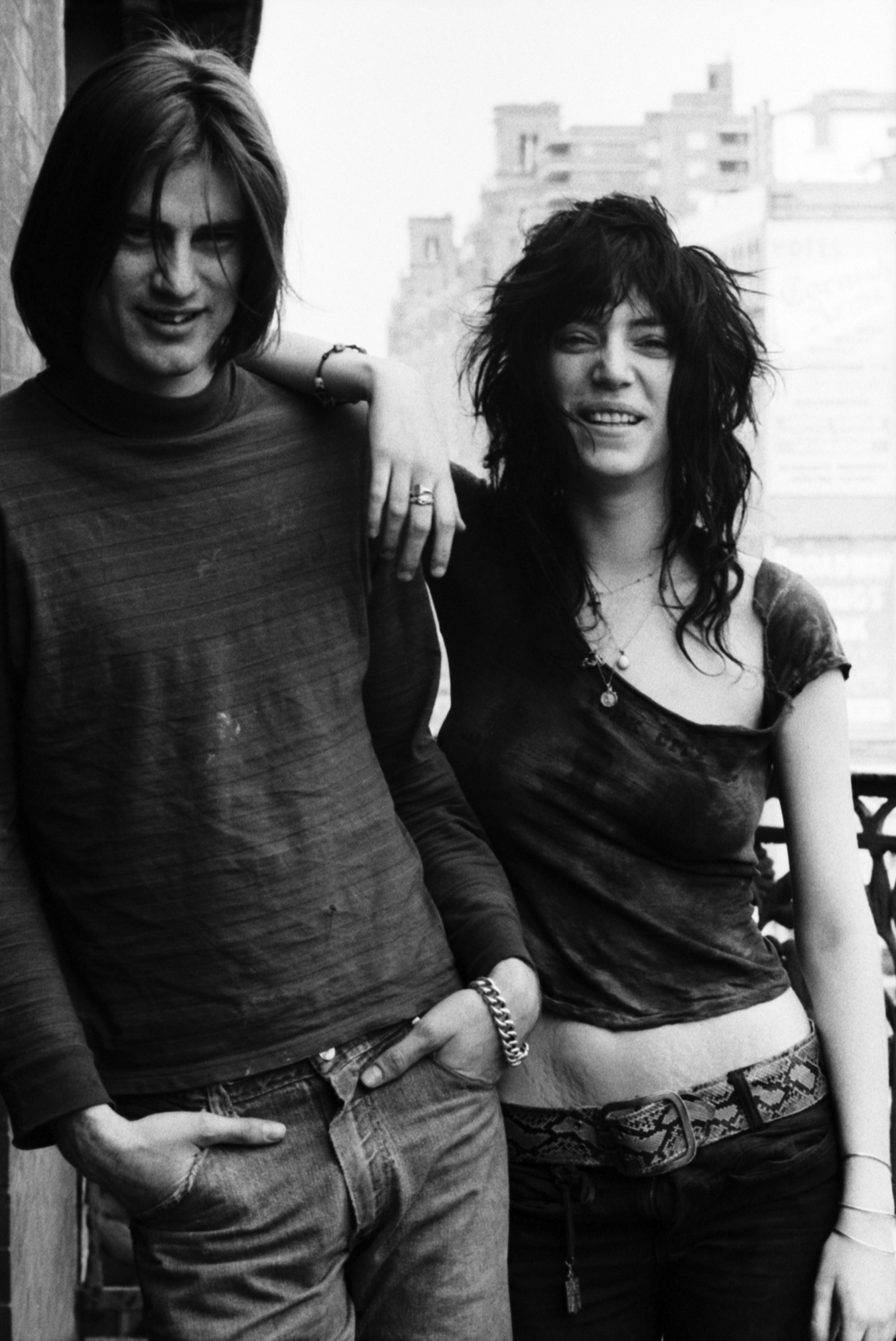

Playwright Sam Shepard and Patti Smith at the Chelsea Hotel New York, May 7, 1971

WHEN THE PHOTOGRAPHER NORMAN SEEFF arrived at Mitchell’s Bel-Air home in 1975, he’d shot her a few times already – the first time after art director Anthony Hudson called off the cuff and asked if he and Joni could drop by Seeff’s house.

“I didn’t even ask what that was for – ‘Sure, I’d love to shoot Joni Mitchell,’” Seeff says, laughing, as he recalls that first meeting. “She was straight-haired, and hippy-ish, with lots of great flowing clothes and ethnic jewellery. I hung a grey backdrop against the wall, and we had the most wonderful time.”

This time, though, they had a mission: shots for her new album, The Hissing Of Summer Lawns. Seeff first shot some anodyne stuff, seating Mitchell on a couch and at her piano. During a break, though, he wandered outside and spotted her pool, with a parapet above offering a commanding view. “I said to Joni, I know that putting a musician in a swimming pool is not anything that anyone does, but why don’t we just do some shots?” he remembers. She didn’t hesitate. “She has the ability to literally surrender to what’s going on. She started swimming, going into these states of reverie.”

Larry Carlton, Robben Ford’s predecessor in L.A. Express

The album’s gatefold emerged from that shoot, Mitchell floating on her back, eyes closed and arms spread. It was gorgeous, but it also cemented Mitchell inside a concept record about suburban ennui, feminine boredom, and seething rage at societal limitations. Suddenly, she was in the centre of the cover’s skyline. “This record is a total work conceived graphically, musically, lyrically and accidentally – as a whole,” she wrote in the linernotes.

Mitchell had previously written, if not entirely about herself, then about her relationship to others – how she saw people she loved or loathed, how they had shaped her life. But the lens was wider on these songs, focused on the weaknesses and wants of those others, not just herself. In the title track, she wrote of how people used money to buy and control love. In Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow, she explored power structures, from God and patriarchy to money and booze, and the failed quests to fight them.

“Battalions of paper-minded males/Talking commodities and sales,” she sang during Harry’s House. “While at home, their paper wives and paper kids/Paper the walls to keep their gut reactions hid.” It was domestic protest music, Mitchell singing for people who wouldn’t sing for themselves.

I knew she was a heavyweight whose music was far beyond any so-called folk-rock person I’d ever heard.

Tom Scott

Fifty years later, Ford remains awestruck by how gentle, pleasant, and commanding Mitchell was during those sessions, his first time in a studio with her. When he struggled with his tone during In France They Kiss On Main Street, for instance, she took him aside. Rather than use his amplifier, she suggested he plug his guitar and distortion pedal directly into the recording console. “I said, Oh, that’s gonna sound terrible, Joan. That’s not going to work,” he remembers. “It totally worked. That’s what you hear on record.”

That experimental confidence defines Hissing, from the way a jazz standard suddenly spills out of Harry’s House to a cacophonous loop of The Drums of Burundi during The Jungle Line, from the electronics that reshape her voice during Shadows And Light to the synthesizer that purrs beneath the title track. Dismissed as “insubstantial music” by Rolling Stone but praised as “delightful torture” by Melody Maker, Hissing’s self-proclaimed wholeness has only bloomed with time. Mitchell was writing, composing, and band-leading her way beyond others’ perceptions.

Seeff says that she never arrived at a photo shoot without a concept again.

Mitchell and L.A. Express saxophonist Tom Scott during a three-night residency at the New Victoria Theatre, London, March 20, 1974.

THE SUCCESS OF THE 1974 TOUR ALL BUT GUARANTEED a full international run for Hissing, but it wasn’t set to begin until two months after the album’s November 1975 release. Meanwhile, rather than retreat to her 40 acres in British Columbia or retire to her Bel-Air home, Mitchell cast herself into one of rock’n’roll’s wildest road shows: the Rolling Thunder Revue. She’d just turned 32.

“Joni Mitchell flies in from the Coast and tunes up in the bathroom. Dylan is a magnet,” Sam Shepard wrote in his Rolling Thunder logbook on November 13, noting Patti Smith and Bill Graham had also arrived. “He pulls not only crowds but superstars.”

Rolling Thunder had careened across New England for two weeks when it pulled into New Haven, Connecticut, the Yale town tucked into a pocket of the Long Island Sound. Mitchell always insisted she had only come to see a show, but she was soon swept up by the enthusiasm and intensity of this madcap assortment of talent, friends, and rivals – Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez, occasional appearances by her Asylum labelmate David Blue. On that first night, she sang a duet with Ronee Blakley and two songs from Hissing. She was in.

“We have another friend that’s with us – it’s a surprise,” Bob Neuwirth said a week later outside of Boston. He would repeat that bit in subsequent shows, as if Mitchell had always just arrived. “We asked her to sing a song for you.”

Courting the spark: Mitchell paints a new impression, 1974.

This didn’t seem an optimal career move for Mitchell, since she would be playing some of the same markets two months later with her own band. Her co-manager Elliot Roberts wondered why she would “make [herself] subordinate to… those old has-beens?” And she didn’t care much about the money, asking to be paid in cocaine so she could “see what this thing is about”. She would stay up late, reading Freud and writing songs. She stole badges from cops. “I kept thinking this is a warrior’s drug. You’d be like Scarface,” she told David Yaffe. “You could have 10 bullet holes in you, and you’d still be shooting.”

Mitchell wanted an adventure, and she now had both sides, good and bad. Shepard had worried in his logbook that Mitchell and Sara Dylan would clash, but it was Mitchell and Baez who seemed locked in contretemps. Baez envied Mitchell’s fervent reception, while Mitchell noted Baez’s access to Dylan. “There was all this horrible behind-the-scenes shit going on,” tour insider Larry Sloman told Dylanologist Clinton Heylin.

There was, however, another outlet for Mitchell: Shepard, the fellow Scorpio who had also just turned 32. A handsome, well-connected playwright with a family at home, Shepard had worked as a rancher and collaborated with Patti Smith. An affair ensued, inspiring songs and sketches that filled Mitchell’s notebook.

“Nobody ever said to Van Gogh, ‘Paint a Starry Night again, man.’ He painted it. That was it.”

Joni Mitchell

“I’ve got this tune that has been growing – started off with two verses, and a couple nights later I added another one,” Mitchell told the crowd at the Montreal Forum on December 4. “Last night, I got a fourth one. I think it’s finished, but I dunno. Maybe there’s a couple more chapters to go? It’s called Coyote.”

Though Mitchell would make minor adjustments to her epochal account of the tryst with Shepard and the tour, she was right: Coyote, the romance, and her run with the Revue were mostly finished. Four days later, having cancelled her own show at the Hollywood Palladium, she joined the Revue at Madison Square Garden for a star-studded benefit for Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter, the professional boxer wrongfully convicted of murder in 1967. Mitchell had her doubts about Carter’s character and the sincerity of Dylan and Baez, but she starred in the show anyway.

“Joni Mitchell blows the top off the place again, just by walking on,” Shepard wrote. “She looks incredibly small from where I’m sitting. Like a vulnerable little girl trying to sing a song she’s written for a huge living room full of adults.”

A woman of heart and mind.

BY THE TIME MITCHELL AND THE L.A. Express began the Hissing tour in Minnesota on January 16, album sales were stalling. Hissing had debuted at Number 130 on Billboard two days before Rolling Thunder’s 1975 finale, then quickly climbed the charts, rising to the fourth spot on 1976’s first index. It stayed there for three weeks before beginning its freefall. The stats were symptomatic of the shows.

“She seemed insultingly ice cold, rarely smiling and never talking to the audience,” read an opening-night review, which took shots at Guerin’s “flat” drumming and Ford’s “annoyingly loud” guitar. “Mitchell showed little energy and enthusiasm.”

She had battled the flu throughout Rolling Thunder, and neither the cocaine nor her smoking could have helped. “I was still in bad health from going out on Rolling Thunder, which was mad,” she told Crowe in 1979. “Heavy drama, no sleep – a circus.”

What’s more, the L.A. Express she’d hired for Court And Spark were falling apart. Sample and Carlton had missed the first tour, but now Scott too had split, replaced by David Luell. Her carousel of keyboardists had turned to Victor Feldman, a London-born prodigy who had played with Miles Davis and Cannonball Adderley but was nevertheless new to this material. “Neither the keyboard player nor the saxophone player were the right guys for that, so it just became uncomfortable,” Ford remembers. “It wasn’t the same.”

Mitchell on-stage at Massey Hall, Toronto, February 10, 1974, during the Tour Of America.

During her Rolling Thunder stint, Mitchell had chased the thrill of newness – romantically, socially, musically. She would perform songs she had finished that day, even play works in progress. She tried this with her own band, not only playing Coyote but also Furry Sings The Blues, a gripping portrait of urban decay and wealth inequality inspired by a confrontational meeting with bluesman Furry Lewis while on the road in Memphis. Outside of Rolling Thunder’s freewheeling atmosphere, the approach could leave audiences cold.

“The response dissipated from enthusiasm to politeness as Mitchell clearly began to lose touch with her audience,” read that first review, not the last dissatisfied notice. At least the gripes were varied. In Georgia, ticket sales were low. In Philadelphia, the sound was horrid. In Louisiana, she stumbled through guitar chords. Dylan walked on-stage for an encore in Texas, but he barely sang.

“Cocaine is a warrior’s drug. You could have 10 bullet holes in you, and you’d still be shooting.”

Joni Mitchell

And then there was her relationship with Guerin. They’d been engaged in 1975, Mitchell even designing their wedding rings and discussing matrimonial plans with her parents. But the turbulence of the road, the affairs, and the jealousy reached a new breaking point when she walked on-stage in Maryland, started to sing Help Me, and split. She did not return to the road in earnest until 1979.

“After the end of my last tour, it was a case of waiting again,” she said just before that run. “I had an idea; I knew I wanted to travel.”

This one’s for the roses: Mitchell in 1975.

MITCHELL NEVER LIKED GAYLE FORD. BY 1976, THE L.A. Express’s early ragtag adventures with Mitchell had given way to private planes and limousines. Robben Ford brought along his young wife, and the tension with the tour’s principal was immediate. Gayle demanded, for instance, Mitchell not smoke in the limo, just one example of what the singer called “queen-bee behaviour”. Mitchell assigned her to wardrobe duty, but her clothes sometimes went missing. “This girl is too much,” Mitchell later joked to Yaffe. “She’s a nightmare.”

After the tour fell apart, Gayle Ford would prove much more useful. Mitchell had accepted an invitation to ride across the country, not as a musician on tour but on a mission. A former lover’s daughter was living with, as Mitchell put it, “wicked twin grandmothers” in rural Maine, her mother locked away in a mental institution. The lover had asked Mitchell and another friend to help him liberate the kid. Again, Mitchell was in.

More than 1,000 miles and two continental divides from Los Angeles, the vigilante trio stopped in Boulder, Colorado. The Fords had moved there after the Miles Of Aisles tour. Having witnessed Mitchell’s struggles on the road, especially with men and cocaine, Gayle had an idea for the singer – visit Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Tibetan Buddhist who had become Allen Ginsberg’s teacher and founded Colorado’s Naropa Institute in 1974. When Rinpoche asked Mitchell if she believed in God, she produced her sack of cocaine and declared, “This is my god, and this is my prayer.”

Joni jamming during the Miles Of Aisles tour, August 1974.

“He didn’t flinch, but his nose started to flare. And I thought, Does he want some [coke]?” Mitchell told writer Michelle Mercer. “I didn’t notice I was being zapped. And then I had no sense of ‘I’ or me, no self-consciousness for three days.”

It was an epiphany for Mitchell, as if a dirty window had been flung open, allowing her to see herself clearly again. She had been stuck between so many lovers and inside so many uncomfortable situations; Rinpoche allowed her to set herself free, at least briefly. Cocaine loosened its grip. “He sees the damage in my face,” she wrote in Hejira’s song A Strange Boy, partly inspired by Rinpoche. “He was the bad boy of Zen,” she quipped in 2013.

After finally reaching the East Coast and cutting her companions loose, she headed south solo, using aliases to elude attention. She headed to Georgia, Florida, and on to Alabama, where she made friends with local musicians, browsed deli meats in grocery aisles, and played it cool when a hotel employee confessed that he knew her real name. She rendezvoused with the revived Rolling Thunder Revue for two May dates in Texas, where a notebook with drawings and lyrics was stolen from her hotel room. To the crowd in Fort Worth she précised her recent travels. “I just quit working and started driving around the countryside,” she said, before acknowledging the allure of Rolling Thunder. “The circus was passing through Fort Worth. So here I came.”

Mitchell kept pushing west, into the American desert, where she spied jet planes and thought of pioneering aviator Amelia Earhart, and herself, or of the difficulties that come with being who we were born to be. “This is how I hide the hurt/As the roads lead cursed and charmed,” she wrote in the last days of her epic haul. “I tell Amelia it was just a false alarm.”

By the time summer began in California, she was back in the studio with Lewy. Guerin was on drums again, Carlton on guitar. A 24-year-old bassist named Jaco Pastorius arrived, too, months before releasing his self-titled debut album. These were her travelling songs, captured on the road alongside Dylan and Shepard, or alone in her Mercedes.

“I was reading the dictionary, looking for a word that meant running away with honour,” she told Crowe decades later. “I saw that word on a page, and it drew me to it because of the J dangling down. I went, That’s the word I’m looking for. That was Hejira.”

Charles W. Bush/Shooting Star/Avalon; Fairchild Archive/WWD/Penske Media via Getty; AP Photo/Alamy; Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images, Shooting Star/Avalon; Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty, David Gahr/Getty, Michael Putland/Getty; Echoes/Redferns/Getty, Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty, Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty; Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images; Ts/ZUMA Press Wire/Shutterstock, Charles W. Bush/Shooting Star/Avalon, Shooting Star/Avalon; Mike Slaughter/Toronto Star via Getty, Henry Diltz/Corbis via Getty