BLACK COUNTRY ROCK

From a home in England’s West Midlands, to Knebworth and Live Aid with Led Zep and back, via fame, fortune, tragedy and musical resurrection – ROBERT PLANT’s come full circle. A new album with local heroes Saving Grace exemplifies his hard rock apostasy, the reason he’d rather worship Nora Brown than hang with Axl Rose. And if all else fails? “I’ll just be an Elvis impersonator!” he tells KEITH CAMERON

Photography by TOM OLDHAM

Travelling light: Robert Plant, packed and ready for his next adventure, Theatre De Verdure, St Malo, July 10, 2025.

THERE’S A GAGGLE OF POTENTIAL customers outside Stanton’s Music Shop in Dudley, doubtless tempted by the window display’s promise of treats within. How about that Ultra 101 transistor radio? The Ekco radiogram? Maybe even a Pye television? More likely the younger eyes are on the latest 7-inch format 45rpm gramophone records, or perhaps the bargain-priced hit-packed 10-inch Stars Of Six Five Special, featuring Britain’s premier class of 1957 rock’n’rollers: Tommy Steele, wild man Wee Willie Harris, and skiffle king Lonnie Donegan with Diggin’ My Potatoes.

Welcome to the West Midlands time machine. Opened in 1895, Stanton’s late Georgian townhouse was demolished in 1959, but it lives again in 2025 as part of the Black Country Living Museum. Established to honour the area’s considerable industrial heritage and bring economic and spiritual renewal in the wake of its decline, the BCLM has included Stanton’s in its recreation of a typical post-war town centre from the region. Here, 10 minutes from its original location, sited next door to a branch of the West Bromwich Building Society and Brierley Hill’s legendary pork butcher Marsh & Baxter, Stanton’s attracts visitors anew.

One such is sat across the counter from MOJO, while a party of curious local school children peer at him through the glass door.

“You could play a gig in here,” says Robert Plant, marvelling at the shop’s perfect acoustics. Black Country born, raised and still only a few miles adjacent – in rural Worcestershire – if not strictly resident, Plant remembers a Stanton’s on Castle Street, albeit he was more intimately acquainted with the new building which replaced the original in May 1961 with an opening ceremony featuring Frankie Vaughan. The design of Stanton’s Mk 2 incorporated the new decade’s boxy modernist features, a recessed entrance overhang affording courting couples a measure of after-hours seclusion. “It was a place where you could pledge eternal love to your future ex-wife,” smiles Plant. “Which I did, and she still enjoys the benefits!”

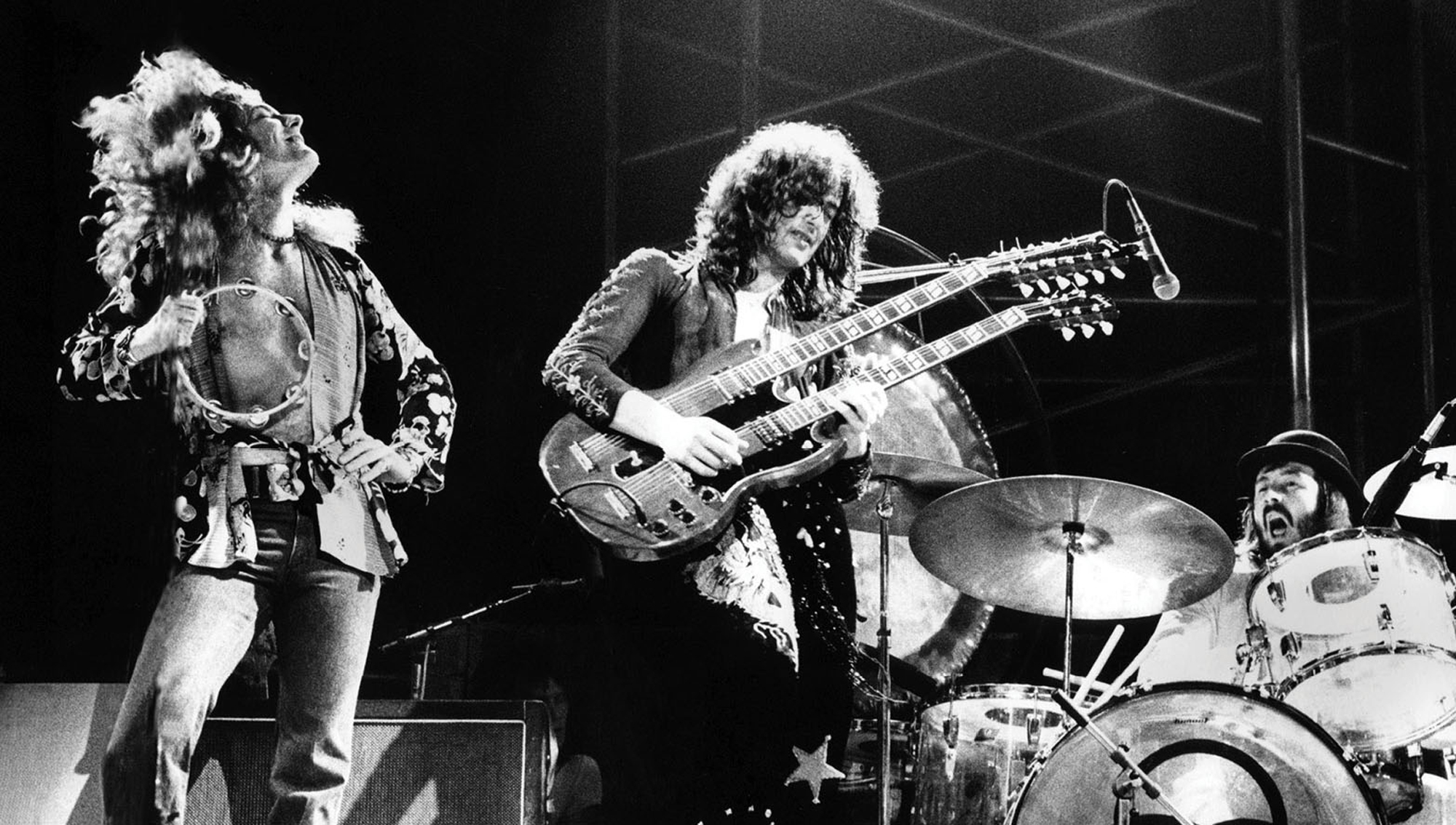

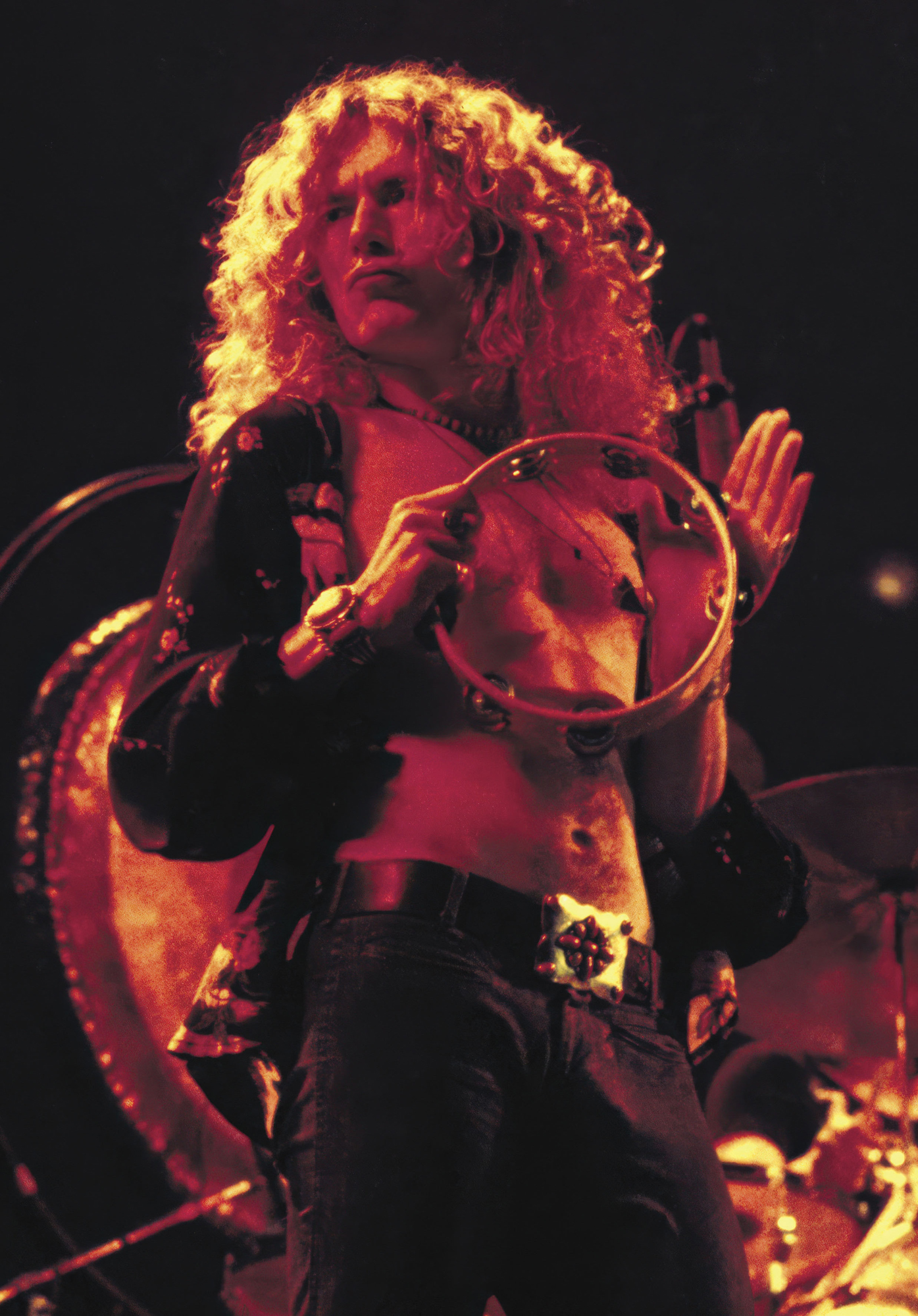

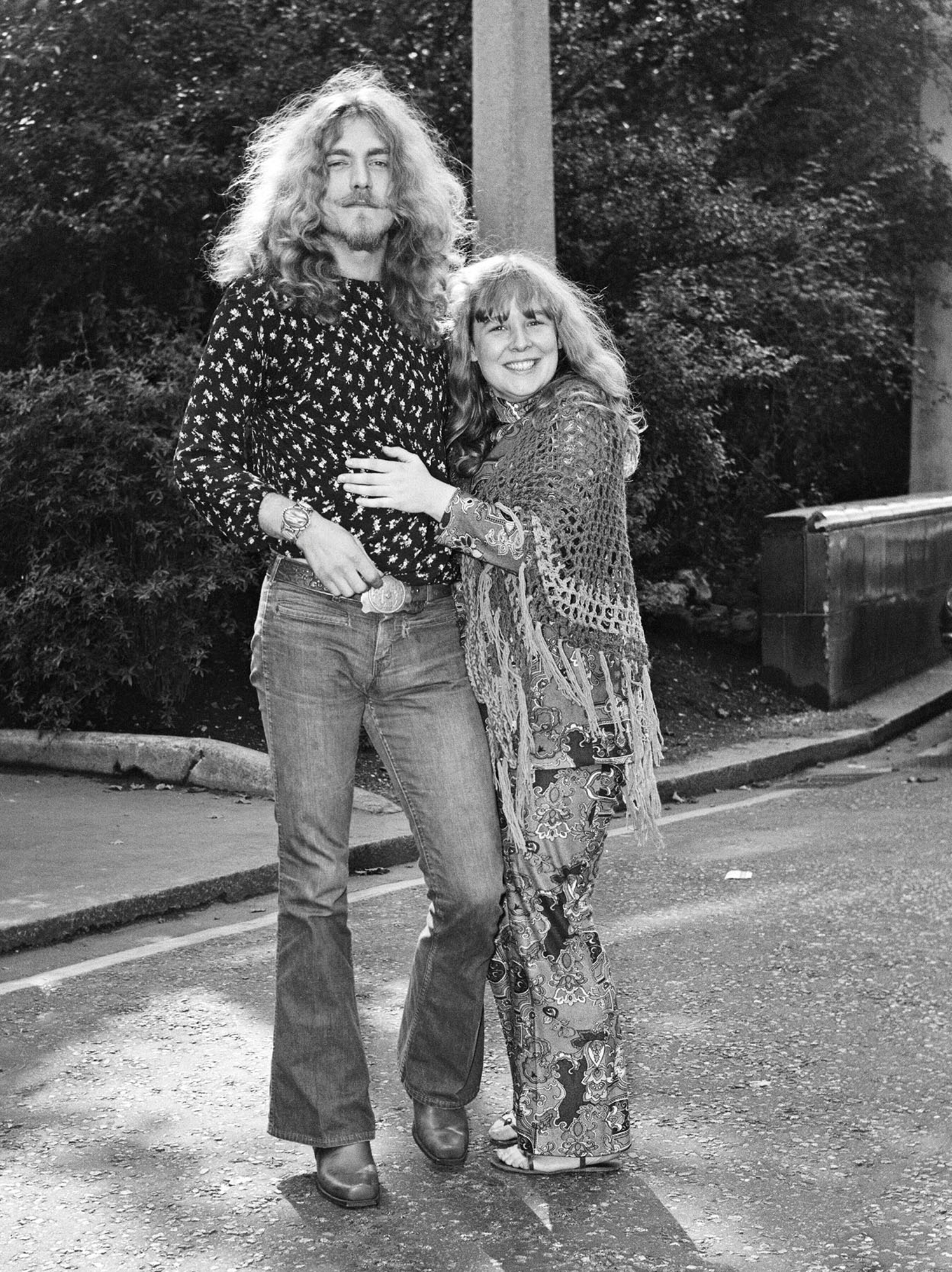

Plenty of neck: Plant deep within the “unearthly condition” that was peak Led Zeppelin, 1975.

AT PLANT’S BEHEST WE MEET HIM IN THE BLACK Country bosom, because it’s the place that gave him life and to which he always returns, most recently 12 years ago when he called time on an 18-month period living in Austin with erstwhile vocal and romantic partner Patty Griffin. Plant’s musical travelogue speaks to his lusts for life and discovery: the monumentalist rock fusion blueprints of Led Zeppelin; his synth-curious solo ’80s then the ’90s rapprochement with Zep’s Jimmy Page; the global roots manoeuvring of his ’00s combo Strange Sensation and its subsequent Afro-trance sibling Sensational Space Shifters; his Americana-scented blues-folk excavations with Band Of Joy; and the hugely successful twin forays into bluegrass harmony with Alison Krauss. Yet however yonder he goes, it seems Robert Plant can only resist for so long the proximity of the Welsh borders, or the lure of a freshly poured pint, possibly while watching his beloved Wolverhampton Wanderers FC.

As the mighty rearranger drains his pre-interview coffee, MOJO recalls a decades-distant Black Country pub crawl which began in Kidderminster, near Plant’s current abode, and thence staggered through Stourbridge into deepest Dudley, including a visit to the Bull & Bladder, the legendary Batham’s brewery tap in Brierley Hill. Plant’s eyes gleam. “You went on a Black Country beer trail? That’s us most nights!”

So familiar is his face, and so deep the ties of family history, that the presence of the singer from Led Zeppelin in any of his local haunts merits little more than a grunt. “All right Rob, still doing a bit?” is as starry-eyed as the regulars get. He admits to knowing some men of his vintage who’ve had “a nip here or a tuck there… and I think, Well, I would rather just enjoy myself.” Looser of jowel yet still handsomely leonine, Plant looks comfortable in his almost 77-year-old skin, aside from the occasional painful reminder that he’s a month away from a partial left knee replacement. Upon climbing out of his Jaguar in the BCLM car park, he was grateful to hand a large bag of records to his friend Trace Smith, who had collected MOJO at Tipton station and with whom Plant has played five-a-side football since the late ’70s.

“I can have a sexy night with a woman and they’ll be asleep within two or three hours of hearing me talk about James Carr.”

“You get a better idea of me by meeting here rather than in the Hyatt in Birmingham,” says Plant, as we settle down in Stanton’s. “You wouldn’t have any idea about the warmth of this area as a place and as a people. I know the story of these places really well, and my family are embedded in it.”

A big figure in that story is his paternal grandfather, Robert Shropshire Plant, who as a member of the Dudley Port Band would play at the bandstand in Tipton’s nearby Victoria Park. “He was a very interesting and eccentric great musician,” says Plant. “He played to the silent movies in the orchestra pit up the road at the Hippodrome, when it could just as easily be Sun Ra because they were playing free-form at times. He played fiddle in that situation, but he was also a trombonist. He also went to see Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, he was only about eight. Buffalo Bill did two shows back to back, one here, one over the border in the dark lands of Birmingham. Imagine how ridiculous that spectacle was for a society that was almost indentured to the great machine.”

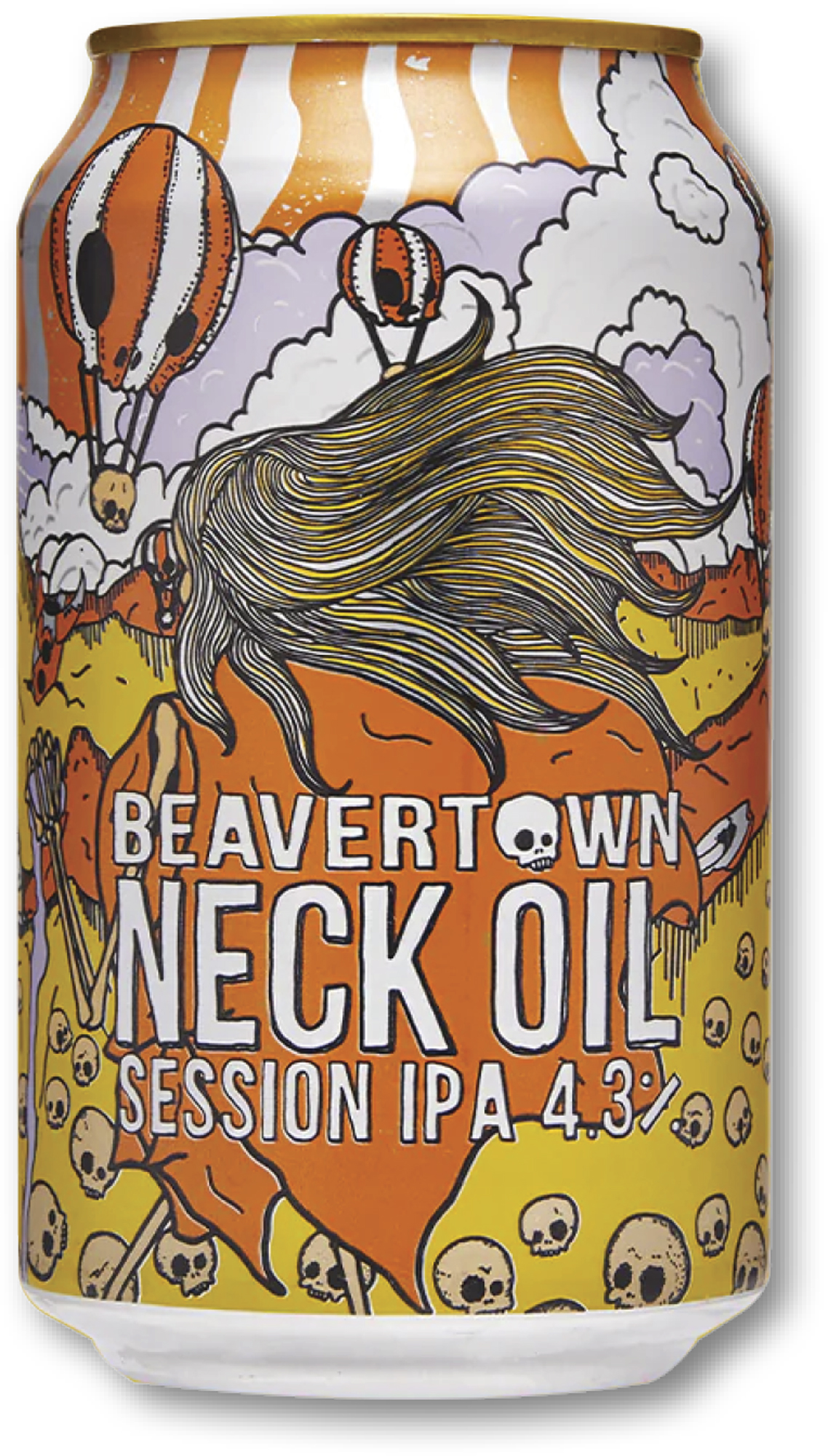

Plant laughs as he recalls Robert Shropshire returning late from the pub to his Tipton terraced house and placing a flat cap on the end of a stick as he walked through the front door to puncture the wrath of his wife. “He advised me to ‘always get plenty of neck oil’…” This gnarled piece of Black Country wisdom gained wider recognition in 2011 when Plant’s son Logan founded the Beavertown brewery and christened its session IPA Neck Oil in honour of his forefathers.

“Dudley’s been much desecrated, the bandstand in the park where my grandfather played was demolished,” says Robert. “But this is obviously a fantastic environment. And the high spots about it all is that when people work really hard, there’s a big, strong community in that group of people, and that’s what I came back for. Because your worth is really just to know who you are. I was constricted wandering around in Austin, Texas, because of a lot of finger-pointing and phones. And should I be worried about that? Not at all, but it was just good to get back here.”

Where there’s none of that?

“Maybe up the Molineux,” he says, referring to the Wolves’ home ground that Plant, now a club Vice-President, first visited as a five-year-old. “Sometimes people have had a few too many pints on the way in and they want a picture for their grandad. It’s getting worse, because it used to be for their dad! But yeah… I came back.”

Plant and Wolves stars before 1980’s League Cup win.

ROBERT PLANT’S LATEST VEHICLE ENABLES HIS roaming instincts without him having to leave the green grass of home. Each member of Saving Grace connects through the West Midlands music community, with varying measures of age and experience. Guitarist Tony Kelsey is a Birmingham scene mainstay who had played in Bev Bevan’s latter-day incarnation of The Move and backed Plant in a version of Satan Your Kingdom Must Come Down at a 2014 charity gig organised by Steve Winwood for his local church. The band’s other guitarist, Matt Worley, ran Strings And Things, a music shop in Stourport, near Kidderminster, as well as the adjacent Swan pub, the focus of a vibrant local scene which Plant discovered upon returning from his Texan adventure. Also passing through The Swan were a young couple, drummer Oli Jefferson and singer Suzi Dian, and Plant credits Worley with coalescing this disparate group, initially for a Swan session in 2019.

“Matt’s a huge figure in what we do,” he says. “Energy, positivity, charm, resilience. He’s the same age as my boy, so his wings were still a little moist, but he already knew about Mike Heron’s Smiling Men With Bad Reputations and the original [Incredible] String Band, the whole Ewan MacColl British side of things. I’d played washboard in the folk clubs before I played harmonica or sang, and I’d seen Ian Campbell and Alex Campbell come through, the unaccompanied singers singing about coal barges that sank… To me, the Robert Johnson stuff was so much more evocative, but Matt didn’t know anything about the myth of the crossroads. So we had lots to talk about and the band built from there.”

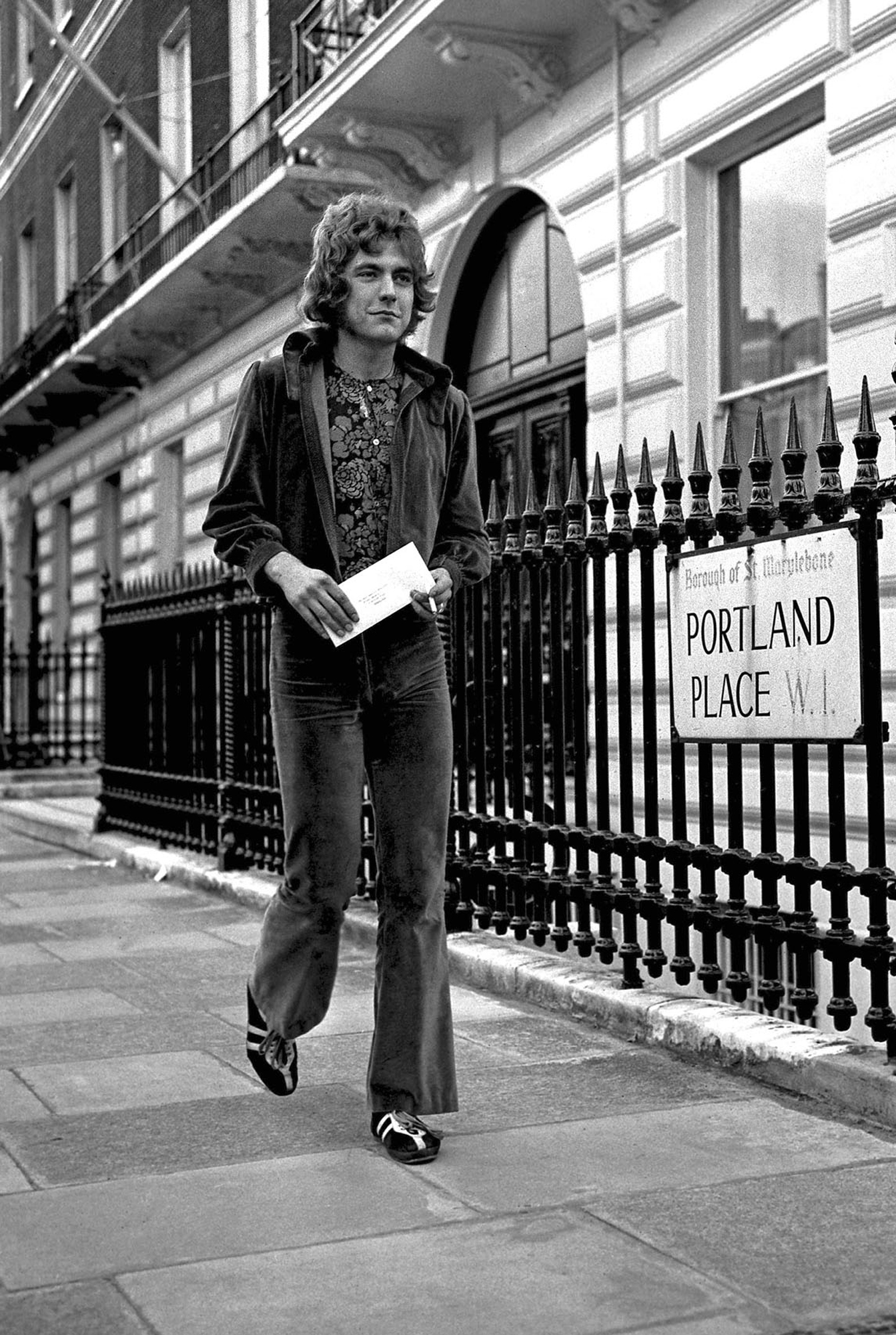

Style counsellor: Plant steps out, 1969

Saving Grace simmered quietly while Plant completed work on 2021’s Raise The Roof, his second album with Alison Krauss. Early tour plans were interrupted by the pandemic lockdown, but their self-titled debut album was eventually recorded at several locations, including Monnow Valley in Wales and a couple of farms in Worcestershire and the Cotswolds. The key analogue from Plant’s previous travels appears to be Band Of Joy: instead of Nashville cosmic country guitar guru Buddy Miller it’s Kelsey and Worley juggling cuattro, banjo, mandolin, and baritone guitars to build a vaporous psychedelic undertow to the ensemble’s extrapolations upon Moby Grape, Low, Donovan, Blind Willie Johnson et al, plus choice selections from the Trad Arr hymnbook. Suzi Dian, meanwhile, is the deceptively wraith-like Patty Griffin figure, her voice melding with, shadowing or overwhelming Plant’s as the song demands.

“Nobody knows what it’s like, for me, having had that journey from 1966 to this today, nobody has a clue. I like that.”

For their first rehearsal, Plant recalls asking Dian to try Gospel Plough and The Everly Brothers’ When Will I Be Loved. “Just to get into something which had a lilt,” he says. “Suzi’s so great because she can sing so delicately and then she can just turn it on. Like the Esther Phillips adage – from a whisper to a scream. And Oli got himself a really good bass drum – calf skin heads, I think it’s a 1942 Carlton – and the sound changed. Because you hit the bass drum, and it takes a while before it finishes its little sonic journey. So Oli became the drone master. On Gospel Plough on the record, there’s a wall air extractor, which was in the barn where we were recording.” He laughs. “‘Extractor fan’ – that’s what they should call my career! How many times have I come bearing false gifts?!”

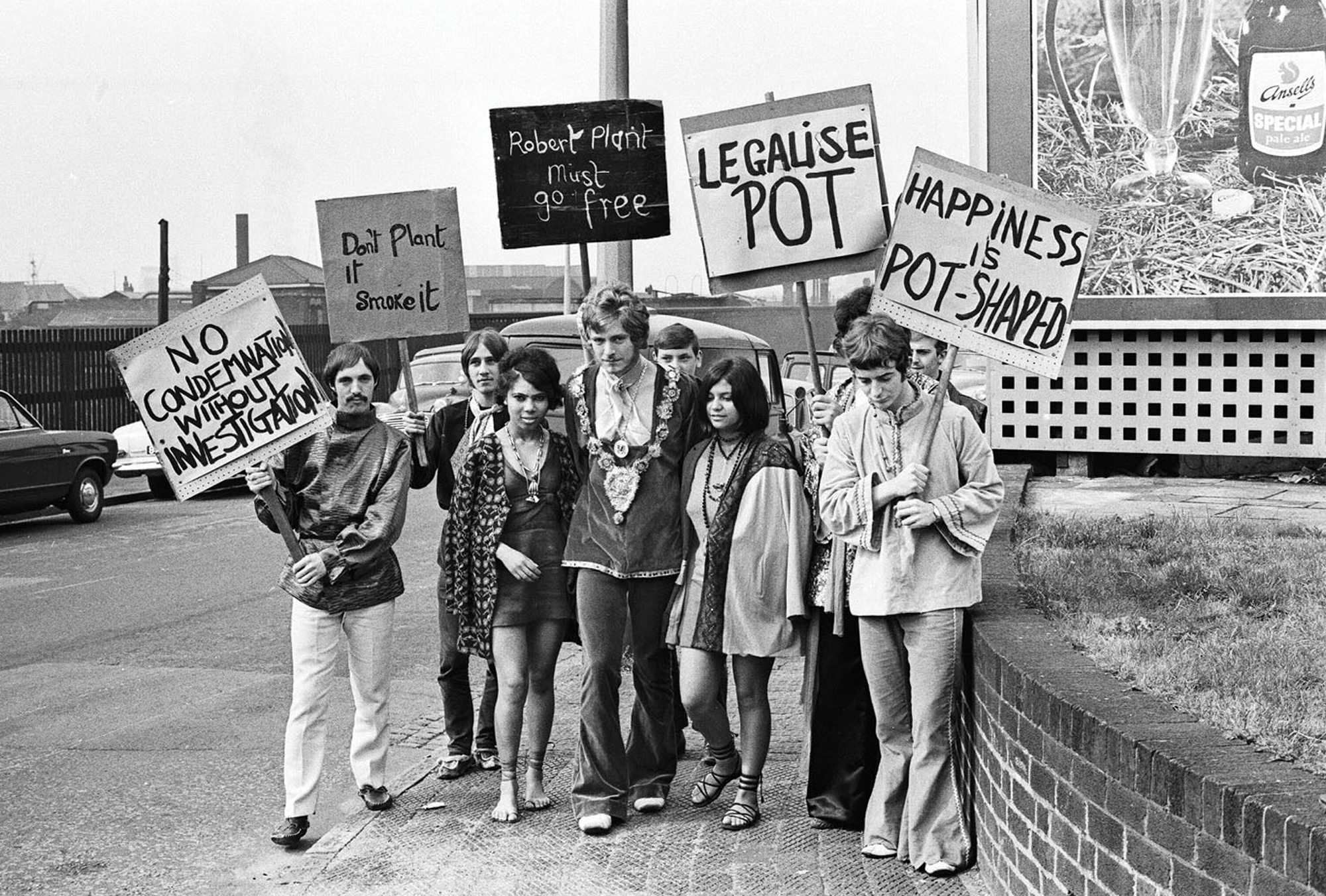

Robert with fans, including future wife Maureen on Plant’s left, outside Wednesbury Magistrates, August 11, 1967

Spend time with Plant yapping about music and it’s not long before your head starts reeling as he leaps between Shreveport and Isfahan, detouring via Ireland and Egypt, and thence from Dundee to Timbuktu – all map reference points in articulating the stories of a lifetime. But his knowledge is lightly worn, and the Saving Grace experience revealed him as much pupil as pedagogue. For instance, the album’s opening track is Chevrolet, a song Plant remembered as Donovan’s 1965 single Hey Gyp (Dig The Slowness). He also knew its 1960 recording as Chevrolet by Lonnie Young and Ed Young. But what he didn’t know was it had originally been written and recorded as Can I Do It For You by Memphis Minnie in 1930 as a duet with her then husband Kansas Joe McCoy. That’s the same Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe who wrote When The Levee Breaks, which Led Zeppelin turned into a signature behemoth in 1971. More recently, Hey Gyp (Dig The Slowness) was covered on 2019’s Help Us Stranger by The Raconteurs, sung by Jack White, a man whose transformative blues skills with The White Stripes and beyond owe a clear debt to Plant and Zeppelin.

“Jack’s incredible,” says Plant. “And it’s not even petty theft. Sweet Home Chicago wasn’t by Robert Johnson, it was Kokomo Arnold, and it’s called Sweet Home Kokomo. But how far back do you go from that? Suzi went to Cecil Sharp House to see where some of the songs on the record came from and it seems like seven or eight people have written I Never Will Marry. So here’s the adventure again. You’re sliding down that rabbit hole.” He laughs. “I can have a sexy night with a woman and they’ll be asleep within two or three hours of hearing me talk about James Carr living in a shelter or something.”

See my friends: Saving Grace, ready to folk at Festival de Poupet (from top) Barney Morse-Brown, Robert Plant, Tony Kelsey, Suzi Dian, Oli Jefferson, Matt Worley, Theatre De Verdure, St Malo, July 10, 2025.

What qualities do Saving Grace bring to you that a different group couldn’t?

First of all, there’s nothing riding on it. This is not something where a record company puts money up and you fly out to some far-off place, and you’re greeted by somebody with a bag of weed. It’s nothing like that at all. The longest journey between the six of us is probably an hour. So it’s fresh. The enthusiasm and excitement is something you don’t just have to sort of plug in or pop into a particular period of time, because this is what they do, and this is what we do. When we started, we were playing information centres on the Welsh borders, in Bishop’s Castle, to 90 people, playing tiny theatres in Cardigan. Where we should play.

Tourist information centres?!

Yeah! And, you know, Theatr Brycheiniog in Brecon. In the Space Shifters we played Nordkapp in northern Norway. It literally was a tourist information centre! Then we got down to Copenhagen and played Roskilde to compensate for that ridiculousness. But yeah, I said, Let’s just call it Saving Grace – because it gets me off the hook. There’s not any likelihood of letting anybody down. Nobody knows what it’s like, for me, having had that journey from 1966, making my first record, to this today, nobody has a clue. I like that, and I like the fact that I might make several more curves along the way. The gigs are small enough so that if nobody wants to go, it’s not the end of the world. And so by having that laissez faire, easygoing, whatever it’s called – suicidal! – attitude, instead of doing the football stadium with some old mates, there it was: we were free. We could mess about.

Rug and roll: Plant and Led Zeppelin tour manager Richard Cole, New York, July 30, 1973; Plant, Kelsey, Dian and Worley on-stage; Jimmy Page and John Bonham give no quarter, Germany, March 1973; Saving Grace in communion, Festival de Poupet, July 10, 2025.

Because you’ve already done the football stadiums with the old mates thing? With Led Zeppelin at Live Aid, the Ahmet Ertegun tribute at the O2 Arena…

I suppose for me, because I’ve been from a very questionable Live Aid to the O2, to Obama and the White House and all those things, I was beatified. I felt the tug of doing this – Saving Grace needed just to move on up in glory, as Mavis [Staples] would say. We’ve got to be very careful now that we make sure it stays closer to Bert Jansch than Axl Rose.

“In the beginning with Zeppelin, there was no T-shirts, no security. Later on, we each had a cop with a gun with us, everywhere we went.”

Today’s elite music careers are pitched at such a heated level: ‘360 deals’, ‘dynamic pricing’, people trying to extract something before a dying star implodes. You seem happier to exist more modestly.

Because I have been to some incredible pinnacles which were unguarded. In the beginning with Zeppelin, there was no T-shirts, no security. Later on, we each had a cop with a gun with us, everywhere we went. But we were really still just kids. So the structure of everything was not covered. Everybody found jobs for themselves on the périphérique of the star quality: somebody to look after you, somebody to offer you something, somebody to coerce somebody not to look after you… All that stuff is just a mess. And because one of my chickens came home long before John [Bonham] passed away, probably three years before that, when I lost my son [Plant and his wife Maureen’s five-year-old son Karac died in 1977], I realised: am I doing this just because I don’t want to let anybody else down? If you bail and you have earth-shattering moments in your life, to get up and do it again is a tough call, because you lose the frivolity of a young man. You go into another world.

Post-Page & Plant, your career trajectory has been a zigzag, never sticking in one place for long. Do you have commitment issues?

Ha! Well, I do but not in music – I’m completely committed to anything that’s really good, absolutely anything that is meaningful. When Page and I got back together in the mid ’90s, I brought in Hossam Ramzy, the Egyptian percussionist. And with him came my guys, Michael Lee, the drummer and Charlie Jones and our friend from The Cure, Porl [Thompson], and Hossam brought in these Egyptians and a couple of Moroccans. The rub between everybody was just incredible, and the filming that we did to go with that, down in Marrakech and Gulmin and in Zagora, almost on the Algerian border, was phenomenal. On the top of the Atlas, the Tizi n’Test pass… something I could never have imagined, and it’s kept broadening my listening and learning. One of the guys would say, “Mr Robert, you have to stay in the same scale.” I said, “Fuck the scales – I’m just having a really good time!” They really did a job on me, led me to [Tinariwen producer] Justin Adams and [Portishead keyboardist] Johnny Baggott and the whole deal of finding people to play tough guitar without it being rock. So the zigzag, a lot of it, has come by circumstance, but it’s a cleansing, because other people’s enthusiasm is new and exciting.

Some of your most notable vocal work has been in collaboration with women: The Battle Of Evermore with Sandy Denny, Raising Sand with Alison Krauss, Band Of Joy with Patty Griffin, and now Saving Grace with Suzi Dian – does it change how you sing?

I don’t think so, no. It depends on the intensity of the song. Alison really pulled me into the idea of singing rather than singing. Because being in a four-piece band for a long time, there was a lot going on but there wasn’t a lot to sing about. Alison said to me at our first rehearsal: “I like singing with you. I like your voice texture against my voice. But how do you expect me to sing a harmony when you don’t sing the same thing twice? Just try it. See what it sounds like…” Alison taught me how to sing properly. And as that first big chunk of our lives together came to an end, and we couldn’t go any farther, I’d fallen in love with Buddy Miller, his sensitivity and his humour in his playing. I found so many people I didn’t know about. I was listening to George Jones, The Louvin Brothers, Clarence Ashley. I felt like a traitor because I’d spent so much time marvelling at the phrasing and timing of Robert Johnson, Tommy McLennan… But then I found this other thing that I would have never given a moment. Buddy was the curator of my new world. So I’m committed to my own love of it all.

Everybody’s song: Plant with Sandy Denny at Melody Maker’s 1970 Pop Poll Awards

MOJO IS MEETING ROBERT PLANT the day before Black Sabbath’s stellar-guest-studded valedictory performance at Villa Park: a textbook example of doing the football stadium with the old mates because you don’t want to let somebody else down. Just a few hours earlier, Plant had been on the phone with Tony Iommi, who asked if he wanted to go to the show.

“I said, Tony, I’d love to come, but I can’t come. Because I know how it will be for me to see Steven Tyler, who I had loved many times as Steven Tyler… I just can’t. I’m not saying that I’d rather hang out with Peter Gabriel or Youssou N’Dour, but I don’t know anything about what’s going on in that world now, at all. I don’t decry it, I’ve got nothing against it. It’s just I found these other places that are so rich.”

As if to prove the point, Plant pulls out his phone and scrolls. “If you don’t know Nora Brown, your world is about to change.” He taps the screen and out comes a version of the Kentucky traditional song Wedding Dress. The Brooklynite Brown was just 16 when she recorded it in 2021, but her chilling treatment rattles like exhumed skeletons in deepest Appalachia, making earlier renderings by The Seegers and Pentangle seem slick and frivolous in comparison.

“She’s got a wooden-bodied fretless banjo that was used a lot by the black musicians,” Plant says. “And I can’t tell you how plaintive her voice is. She’s found a lot of the songs that I found, and she’s found songs I haven’t found. This is how we open our show now, with this song.”

Alison Krauss and Plant at New Orleans JazzFest, 2008

Plant happened upon Nora Brown playing 2024’s Cambridge Folk Festival, which Saving Grace headlined – a statement performance just five years since their early gigs opening for Fairport Convention.

“We folk people now!” he laughs. “Patty Griffin always used to say to me, ‘Hey! Let’s make an album! We’ll call it… Folk Off!’ So that’s the adventure – you become part of this fraternity of explorers. With Saving Grace, it’s a very new adventure. We all have fun. Everybody takes a gin and tonic at the end of the set before the encore. I always say, Don’t hold the glasses during the encore, because it’s usually an a cappella piece and we’ll look like the fucking Dubliners if we’re not careful! I see really good things happening.”

Another recent connection illustrates where Plant’s head is at, and how far he’s removed from the legacy Zep-rock hinterland. On Paul Weller’s new album of deep-cut covers, Find El Dorado, Plant contributes blues harmonica and a verse of vocals to Clive’s Song, written by Incredible String Band co-founder Clive Palmer and originally recorded in 1971 by Scottish folk hero Hamish Imlach. Plant is clearly still bubbling at meeting a fellow seeker.

“What a miner for songs he is,” he says. “I think Paul is onto something great. With Steve [Cradock] with him, the two of them have got a really good thing going. I like Paul because he’s sharp. Whereas I’m a bit wishy-washy, sort of peace and lovey.”

He’s a Mod – sharpness is baked into the religion.

“D’you know, they found a picture of me coming out of a court in West Bromwich! And not the court of the Crimson King either – I’m coming out of this courtroom and I’ve got a pair of trainers on… I get this call – (adopts very plausible Weller voice) ‘Perce! What are those fucking trainers?’ I said, Well, I don’t know – I don’t know where I was living then. I wasn’t living at home, I was living in a van or something. ‘Oh, man, if you find them…’ And I suddenly thought, Next time I go to Gambia or southern Morocco, I can get loads of trainers, I can make a fortune out of Paul and Steve! But I think Paul’s great. He’s got a good root about him.”

Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant with arts and politics luminaries at the Kennedy Centre Honours Gala, Washington DC, December 1, 2012.

When we get to a certain age, assimilating new things becomes more difficult, and many people settle for what they know. They stop taking stuff in, or giving much out. In terms of music, Weller’s not like that, and nor it seems are you.

Well, at the end of my first formative period, I was in what you’d loosely call the biggest band in the world. The fervour that surrounded that, it was an unearthly condition and because of its terrible finales, I got suddenly launched into that post- Zeppelin thing where I went, I’m never gonna play any Zeppelin stuff again. I’m gonna get a TR 808, and write Big Log, or Fat Lip, whatever it was. But I was on my own, and Atlantic, Ahmet and people like that, were saying: “Why don’t you put the band back together?” I said, Look, I’ve made a record called Shaken’n’Stirred. Nobody likes it, but I like it. Fuck it. Nobody liked Zeppelin, but we liked it. Fuck it. And if it ever gets to another point where it’s not like that in my quantifying of it, then I’m lost. I’ll just be an Elvis impersonator. I’m really good at doing Elvis!

So you’ve never been tempted to just do what most of your contemporaries are happy to do – kick back and play the hits?

What were the hits? How can they be related to now, where do they fit? They fit as a sort of memoir… When people say that I don’t like Stairway To Heaven, I just don’t like the idea of it. These iconic things – they’re just what they are. But you know, most people have missed some of the best Zeppelin stuff. For Your Life, on Presence. Achilles Last Stand! Fucking hell. Just extraordinary that three people and a singer can do that. Really, they were pulling so much stuff out of the unknown, Bonham and Jones together on For Your Life. It’s just insane. And Jimmy, just… (exhales) I suppose, to do it for the sake of it was never what Zeppelin was about. And the tribute to Ahmet, it came through. You know, without John, but it came through. It was a good study. The smell of fear on that stage was quite remarkable. Because we’ve been shambolic at times, and great other times. That’s how it should be if you’re taking risks like that.

“Achilles Last Stand! Fucking hell. Just extraordinary that three people and a singer can do that.”

Google AI doesn’t refute rumours of a Led Zeppelin reunion.

Yeah, isn’t that great! They’re just trying to get me used to the term ‘AI’, as if I’m embracing it. AI’s about extortion. Maybe it’s just a way of flogging tickets to something that never happens.

“It’s not yesterday’s achievements, but today’s targets and tomorrow’s goal that give us a reason for being and not simply having been.” That was you, writing in the first Robert Plant solo tour programme in 1982.

Really? Wow.

I suspect your mission statement now wouldn’t be much different.

Yeah. Except then I was trying to justify myself to an audience that didn’t want it. And a record company.

That audience may well have been your former bandmates.

Oh, to say the least, yeah. And not just the once! (laughs) But the thing about that is, everything had to change anyway. I think Paul Weller’s got a great audience, but he always says, “I know what they want…”

Which doesn’t mean he gives it to them.

(Laughs) I said, Yeah, you know what ‘they’ want. I know what ‘they’ want, but who the fuck are ‘they’? I’m one of ‘theys’. I’m a ‘they’! I went with Miss Pamela from the GTOs to see Dion DiMucci at the Aladdin about 10 years ago in Vegas. And he was fantastic. He’s got that Italian scat stuff, Born To Cry and Lovers Who Wander, but like they, I was going, Come on, it’s got to be The Majestic! What about Hoochie Coochie Boy? What about Ruby Baby? Come on! And he sang Abraham Martin And John, and I was going, Well, yeah, it was a very important song… But! Come on!!! So I really sympathise with ‘they’. They remain the same.

You do play some Zeppelin songs with Saving Grace, albeit the likes of Friends and Four Sticks and The Rain Song – ie, not the obvious ones and in a very different contexts to the originals.

Exactly. I think it does work, though. It works for me, and it works for the band. Feels like ‘they’ won’t be so distressed.

Been a long time: a newly formed Led Zeppelin, London, December 1968 (from left) Jones, Page, Plant, Bonham.

WE EXIT STANTON’S, RETURNING DUDLEY’S venerable music emporium to the Black Country Living Museum visitors. On the replica 1950s street he obliges a young woman in a Boston T-shirt with a selfie, and another who tells him Stairway To Heaven is “actually the greatest song of all time”. Plant winces, possibly from the pain in his knee. By the time that’s fixed, Saving Grace’s debut album will be out and the band touring America. How, MOJO wonders, does someone so invested in a globalist discourse, deal with the dire geo-political state of things?

“I’ve spoken to two or three companions in America recently, and the first thing they do is apologise. The conversation immediately goes to the question of sanity. How do I deal with it? There are people I know that say I should say what I think, but there’s so many strands to it. It’s a slow death of everything we ever loved. From an American viewpoint, I could only add my support to Bruce Springsteen because he actually knows it, he lives in it. If we talk about Britain, what can I say? The mess remains. I have my opinions, but the best thing I can do is try and make people feel OK when I play, and maybe be slightly ridiculous between songs.”

Plant’s recent curatorial orientation, however rewarding, comes at a price: his songwriting. His two albums prior to Raise The Roof, the Sensational Space Shifters-powered Carry Fire and Lullaby And The Ceaseless Roar were two of his greatest, powerful dispatches from the personal and global frontlines, as Plant looked within himself, and repeatedly found “the song that never dies”. Might his roving spirit permit one more such journey?

“It’s possible,” he says. “I’ve got lots of anecdotal couplets, but what I need is long loops of music – flat, one-chord grooves where I can create melody. I did it really well with Justin [Adams] and Johnny Baggott. They came with their own condition, which is brilliant. What we have in Saving Grace now, we can do all sorts of trips in a very demure way that can fit into the way that impresses me to write. We can make it trippy, and that’s where it belongs, this whole deal. So, yes, I think there’s every likelihood.”

Plant offers MOJO a lift back to Tipton station. We hit traffic just past the statue of William Perry, AKA the Tipton Slasher, England’s 1850s champion heavyweight boxer, and with the Jag’s satnav mute, MOJO’s phone re-routes us around Victoria Park. “This is a none-more-Plant odyssey,” the singer exclaims. He slows down at 91 Park Lane East, the very house where Lord Neck Oil did his hat on the stick trick. Further along the same street, Plant points out where his father, another Robert, was born.

“I used to have two cats, Dudley and Tipton,” Plant muses, “because my mum came from Dudley and my dad from Tipton. I just wonder – how’ve we got to an era where what we loosely call my peer group are writing books? Because they can’t get it in the book. All this stuff that I’ve experienced, so many adventures, so many tales – it’s fantastic, you know. And I wouldn’t even remember them if I wasn’t talking to you. It’s a big story.”

Too big for a book?

“I’ll never write a book.” He smiles and offers his hand. “What did Donovan say? ‘What’s been did’s been hid.’”

lighting by James Hole and retouch by Ryan at Milk and Metal; Chris Walter/WireImage/Getty; Cyrus Andrews/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty, Jerry Zolten/Dust-to-Digital, PA Images/Alamy, Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix via Getty, David Bagnall/Alamy; Tom Oldham (5); Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty, Express Newspapers/Getty