Rebel Music

Fifty years ago, WILLIE NELSON up-ended the tyranny of the Nashville Sound with a record like nothing before or, perhaps, since. The road to Red Headed Stranger was long and uphill: strewn with broken marriages, record label wrangles and acts of God, but it transformed his fortunes, and his image. “It got to be a cool thing to like Willie,” discovers STLVIE SIMMONS.

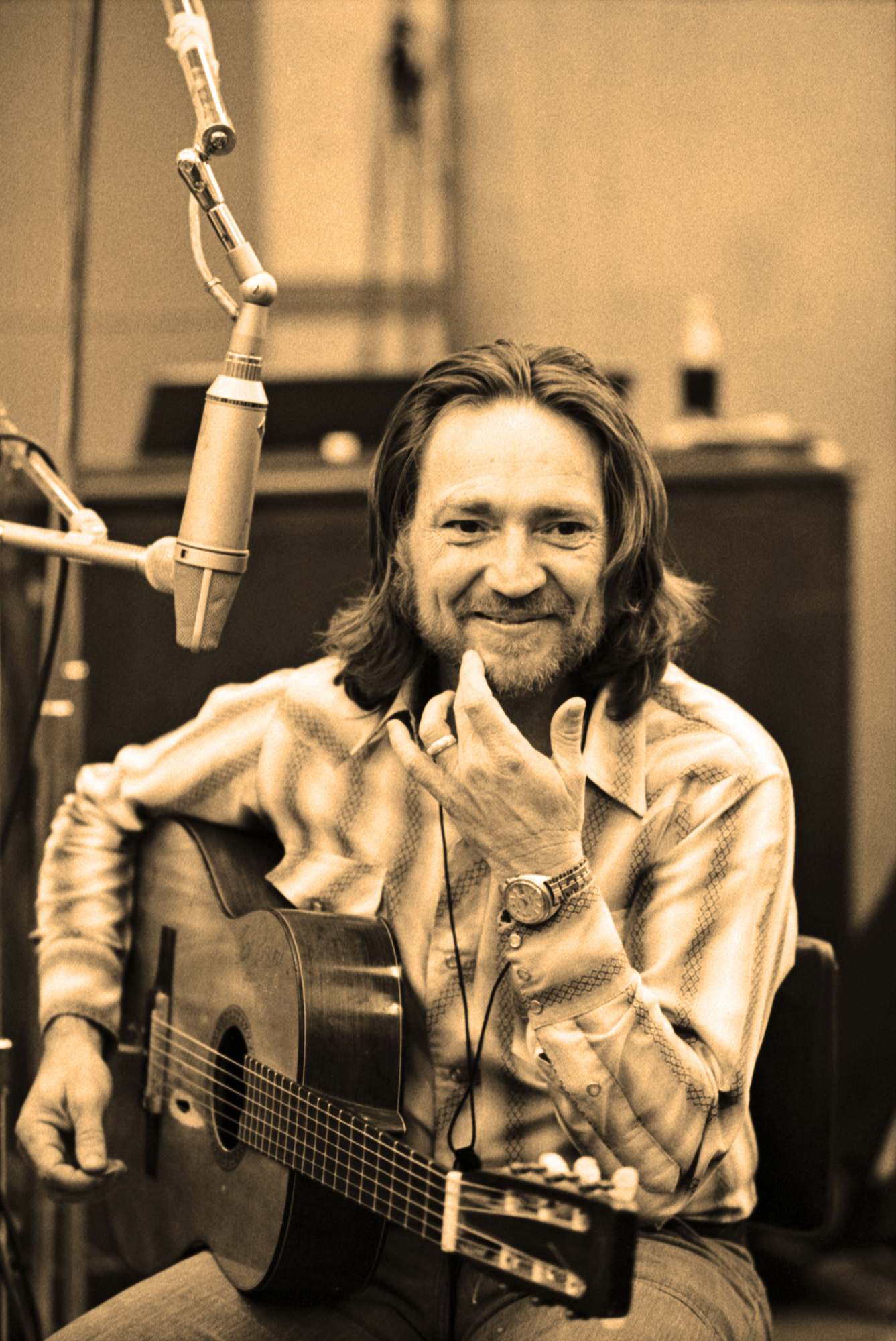

Portrait by DAVID GAHR

Thank God I’m a contrary boy: Willie Nelson prepares to break the mould, Atlantic Records studios, New York City, 1973.

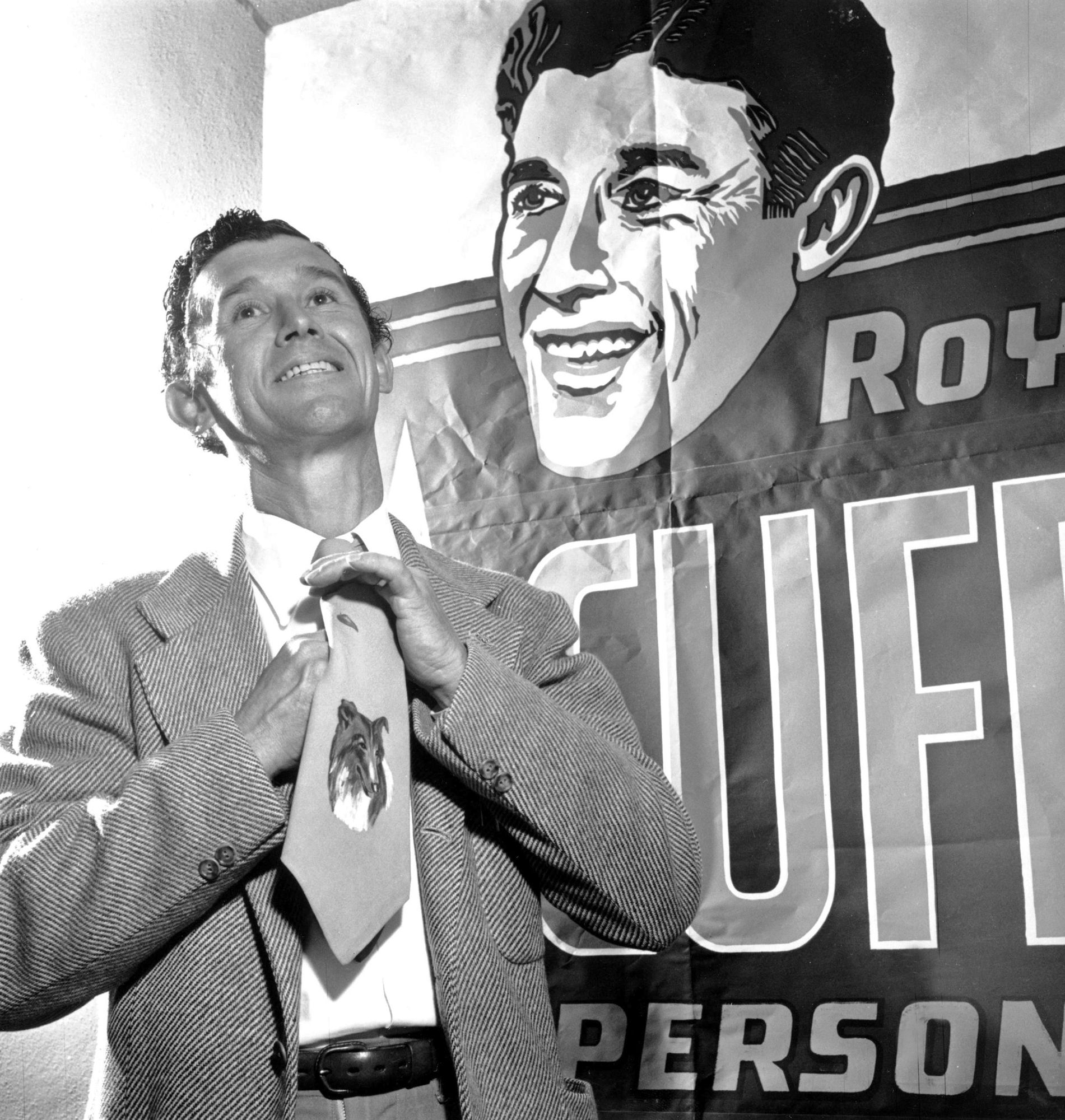

NASHVILLE, 1975. BACKSTAGE AT THE GRAND OLE OPRY, THE MOTHER Church of country music, Willie Nelson lit up a joint. As the scent wafted out of the door, Roy Acuff, the King of Country and de facto Opry ambassador, grumbled aloud about “the hippies down the hall”. Here were two celebrated artists in Nashville’s most cherished country institution. Acuff, 30 years Nelson’s senior, was the old guard, and Nelson, by his own description, was somebody who didn’t fit into any of the slots.

Nelson had great respect for country’s old guard; it was largely the music he grew up on, along with Frank Sinatra, Django Reinhardt, Louis Armstrong and the Mexican musicians who lived across the road from the Nelsons in Abbott, Texas. And Nelson and Acuff had something in common. Both had recorded covers of the Fred Rose ballad Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain. Acuff’s was released in 1947, when Nelson was 14, an aspiring recording artist and already a songwriter. Nelson’s version was on an album that came out earlier in 1975. It was his first record for his new label Columbia Records: Red Headed Stranger.

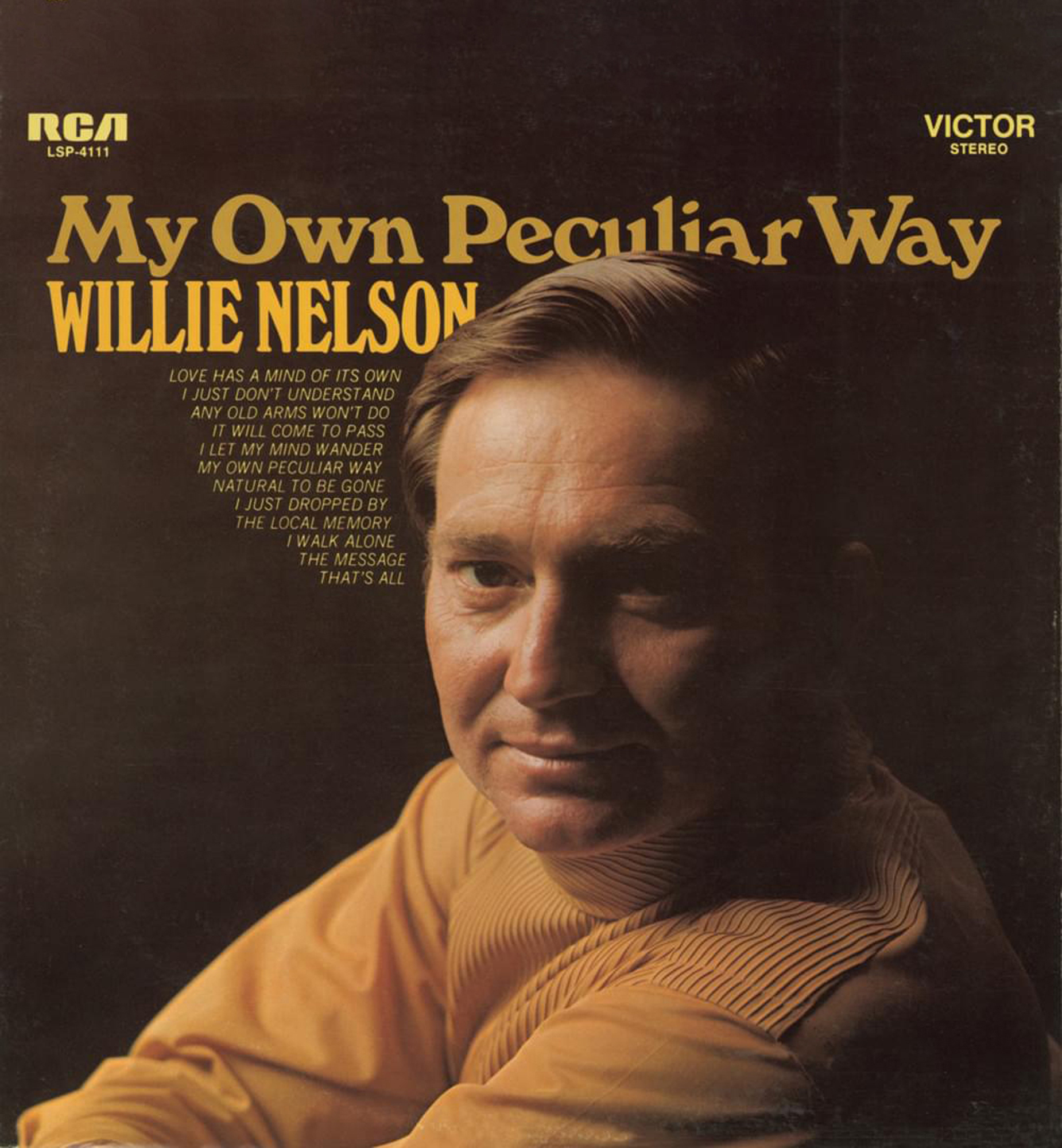

Straight and narrow: Willie Nelson in 1967.

When Columbia released Nelson’s Blue Eyes Crying as a single, they weren’t expecting much. Then again, they felt the same about the album. Raw and unpolished, there was nothing on it that sounded anything like a country hit to them.

But the sparse, intimate ballad flew to the top of the country charts, Nelson’s first Number 1. It also crossed over to the Billboard Top 100, one rung short of the Top 20. It won Nelson his first Grammy: Best Country Vocal. That might well have been a surprise to Nelson too. As he told the US radio show Fresh Air in 1996, he was no Eddy Arnold – the iconic, smooth-voiced country-pop crooner of the ’40s. “My phrasing was sort of funny,” shrugged Nelson. “I didn’t sing on the beat.”

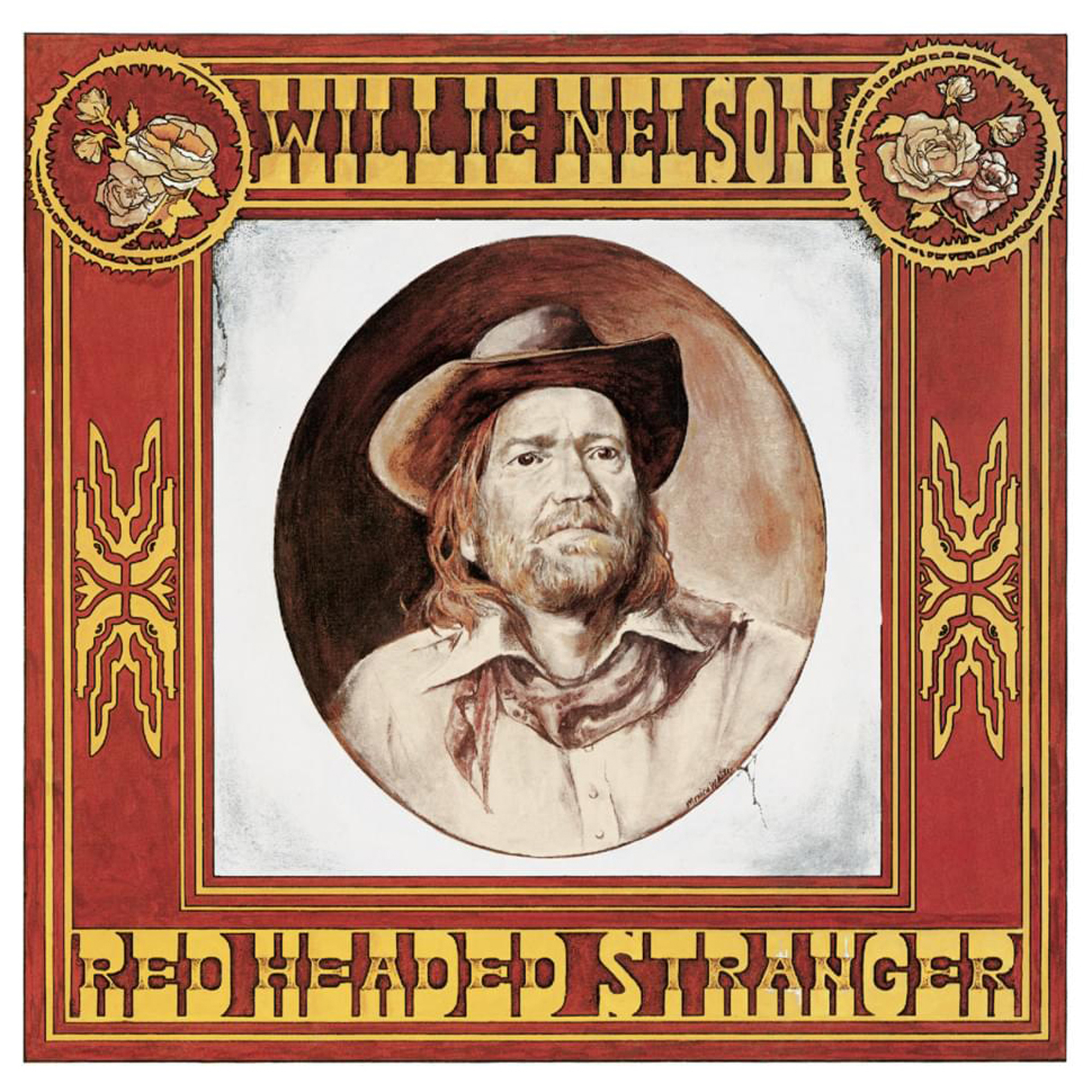

Red Headed Stranger didn’t have ‘hit’ tattooed over it either. It was a strange gothic-noir western concept album, made up largely of cover songs, its production skeletal. When Nelson played it to his record label and manager, they thought it was a demo, unreleasable as was. Willie’s friend, the country star Waylon Jennings, spoke to the record company president, calling him a “tone-deaf, tin-eared son of a bitch”. As it turned out, under the terms of Nelson’s contract, they had no choice but to release it as Nelson wanted it. And now there it was at Number 1. It went on to sell more than 2 million copies and propelled Nelson to superstardom.

17-year-old Willie in 1950.

DURING THE HALF-CENTURY SINCE ITS RELEASE, music historians have argued over the impact of Red Headed Stranger. It’s been hailed as the pioneer of everything from Outlaw Country to Americana and plenty in between. For Nelson, it was finally finding a place in country music where he fit.

“My songs had too many chords,” he said in a radio interview. “Country songs weren’t supposed to have over three chords, according to executive decisions. And I wouldn’t take orders. I didn’t know how to take direction that well. So I wouldn’t fit in any of these slots, and so I became one of those guys that, you know… they had to call me something else.”

Roy Acuff, guardian of the old ways.

At first they called him “troublemaker”, he said. “And then they found the word ‘outlaw’.”

Waylon Jennings arguably held the rights to ‘Outlaw Country’ since it was Jennings’ PR Hazel Smith who came up with the phrase. What’s uncontestable is that Red Headed Stranger was groundbreaking. It showed that a country artist could ignore the rules of the Nashville Sound, tear up its manicured landscape and still be a country artist with a hit.

The Nashville Sound was Nelson’s nemesis. Part compulsory style sheet, part music business 10 Commandments, it coalesced in the mid-’50s and Nelson knew the man behind it: Chet Atkins, the guitar player, producer and Vice-President of RCA. Nelson signed with RCA in 1965, after his first two albums on Liberty, and stayed with the label for 13 albums until 1972.

Nashville Sound architect Chet Atkins.

When asked to define the Nashville Sound, Atkins said “It’s the sound of money.” Country records weren’t selling as well as pop, so the answer was to make country records sound less like traditional country and more like pop. All rough edges had to be smoothed and all production had to be polished. In the studio, singers would not be backed by their own bands but top-end session musicians, the Nashville A-Team. There would be strings and backing singers and a producer well-versed in the sophisticated art of lush.

Nelson had no love for this statutory frou-frou, often added after he’d finished in the studio and was back on the road. Decades later, Mickey Raphael, the harmonica-player in Nelson’s ’70s band and a big fan of his boss’s RCA-era songs, took it upon himself to get hold of the multi-tracks and strip them down.

“I took all the strings and the sweetening off of it to just Willie and the band, all studio cats,” he tells MOJO. But when he played the remixes to Nelson, the singer was bemused.

“Willie said, ‘I don’t get it, what did you do?’” because the tracks sounded exactly as he remembered recording them. In 2009, RCA released Raphael’s mixes of songs from 1966-1970 as Naked Willie in the US, and in the UK as Willie Stripped.

Nashville had been Nelson’s home since 1960, and it had been the scene of significant songwriting success, with hits including Crazy – a Billboard Top 10 for Patsy Cline in 1961 – and Funny How Time Slips Away, a hit for several artists. But after 10 years the city had soured. At the end of December 1969, after his home in nearby Goodlettsville burned to the ground (he managed to rescue a pound of weed, and his guitar, Trigger), Nelson took a break, then in 1972 he moved back to Texas.

Nelson singing with future second wife Shirley Collie, Riverside Park Ballroom, Phoenix, Arizona, December 13, 1962.

AUSTIN, 1972. TEXAS’S STATE CAPITAL WAS A COUPLE of hours drive from Abbott, but in other respects on another planet. The city had a motto, “Keep Austin Weird”, and the 225,000 who lived there back then did a pretty good job of adhering to it. Austin was a liberal oasis in a conservative state. Housing was cheap and so was tequila, beer and pot. In the early ’70s, its population included plenty of hippies, students and a good number of country music-loving good old boys who flocked to its countless rock clubs, blues dives and honky tonks. This was manna from heaven to Nelson, who at this point just wanted to play live. He had spent much of what he had made from his songwriting paying for tours he wanted to play but the record company, given his less than stellar album sales, didn’t want to fund.

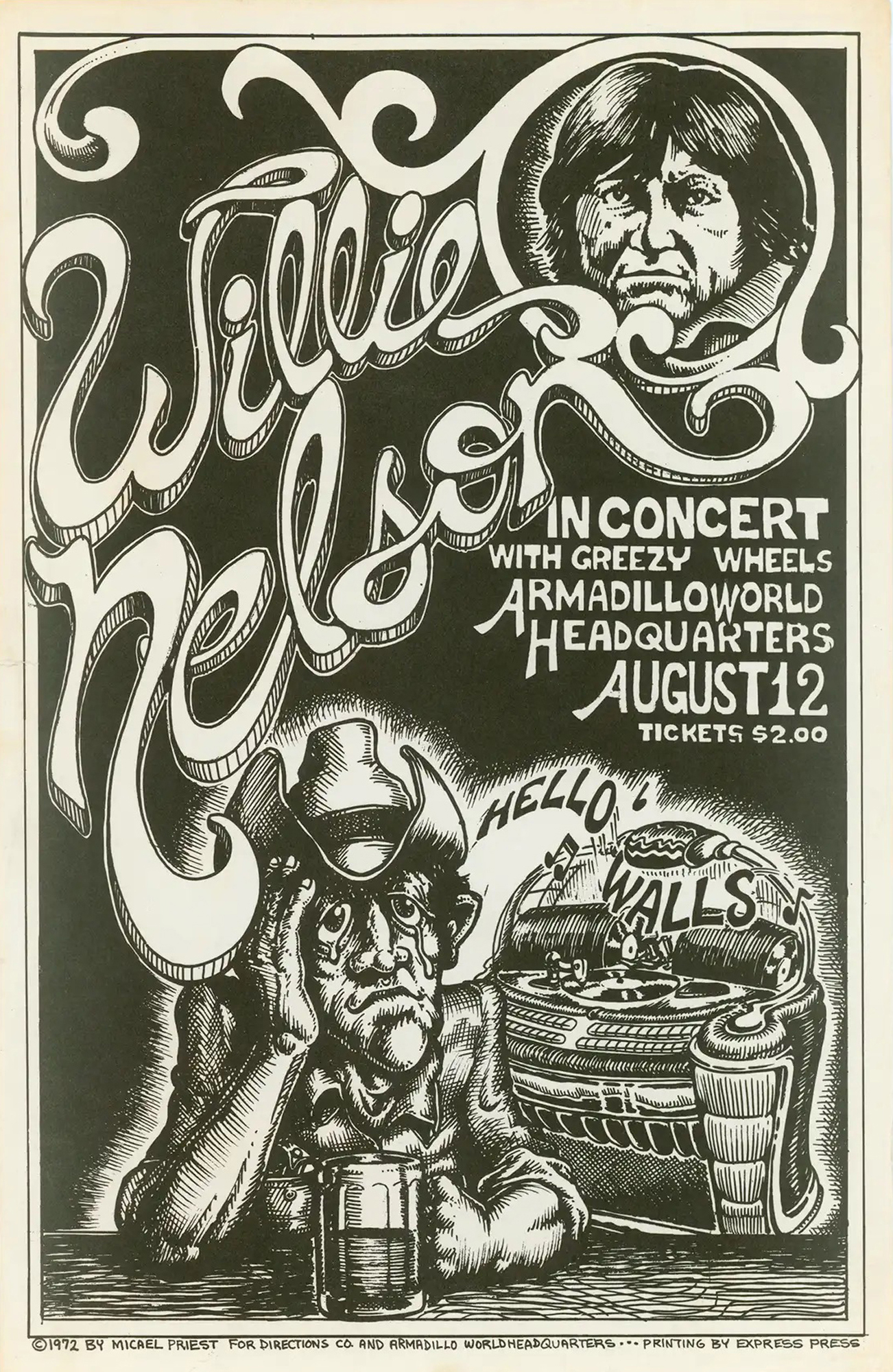

One of the bigger stages in Austin was the Armadillo World Headquarters, an arts centre and concert venue that two years earlier had been an abandoned armoury for the Texas National Guard. Everyone played the Armadillo – from Ray Charles and Bill Monroe to Frank Zappa and Van Morrison.

Nelson debuted at the Armadillo in August 1972. The poster for the show was a psychedelic, Cosmic Country drawing of a thoughtful-looking Nelson in a cowboy hat, nursing a beer beside a jukebox playing his song Hello Walls. The crowd of around 1,600 was a mix of rock and country fans, until then an unheard-of crossover. According to Nelson’s 2016 memoir, My Life, “Rednecks and hippies who had thought they were natural enemies began mixing without too much bloodshed. They discovered they both liked good music.” That said, there were still places, including the notorious Broken Spoke, where a longhair hoping to hear country music might not get out alive.

Nelson, though still neatly cropped and less than a year away from his 40th birthday, was drawn to Austin’s hippies and their ideals, ending up playing anti-Vietnam benefits and fund-raisers for the Democratic candidate in the 1972 Presidential election, the arch-liberal George McGovern. On a TV interview in Dallas, Nelson sang Austin’s praises as a place “where people can be themselves and not have to worry or be uptight about anything”.

“I never really worried too much about what people thought. That has been a positive and a negative for me along the way.”

Willie Nelson

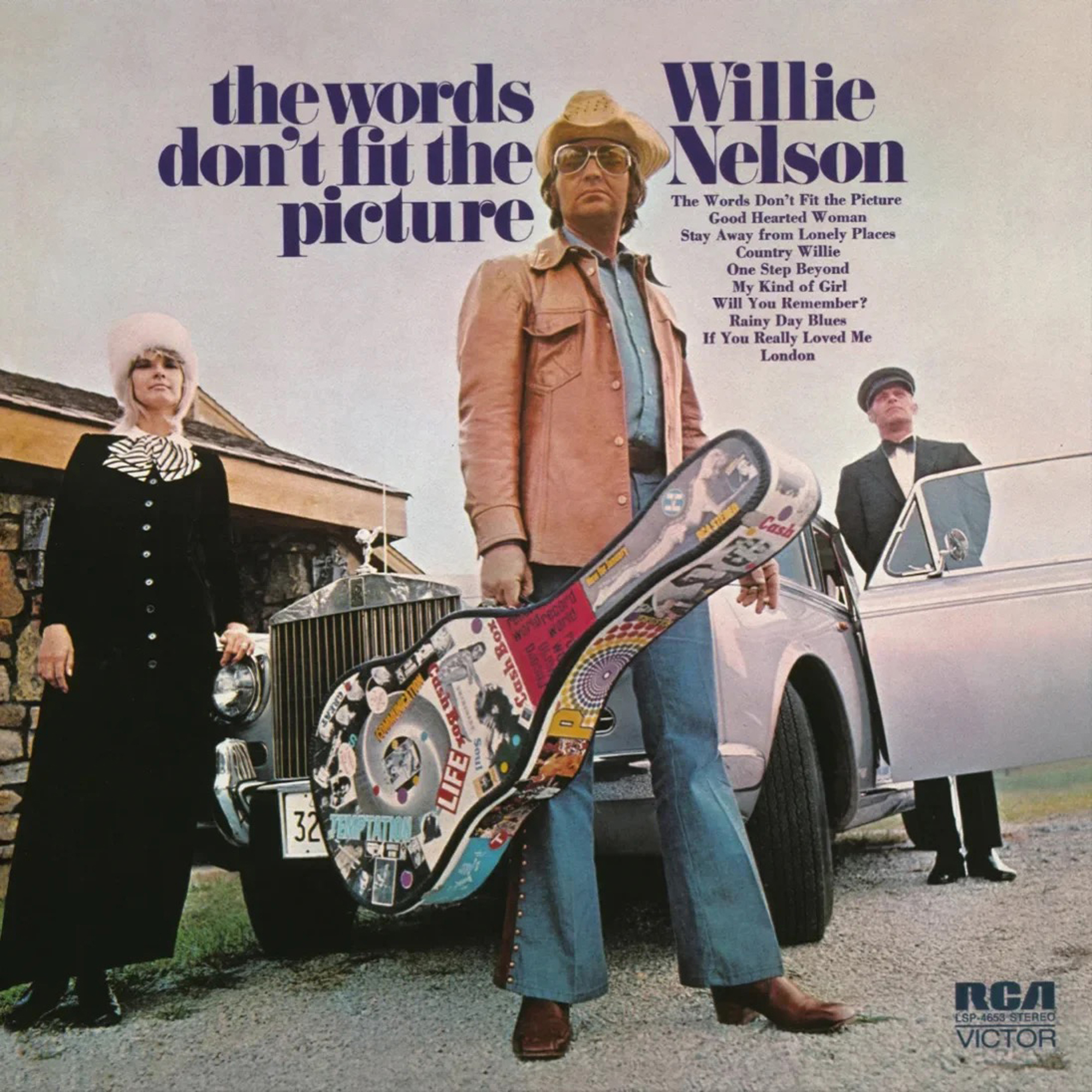

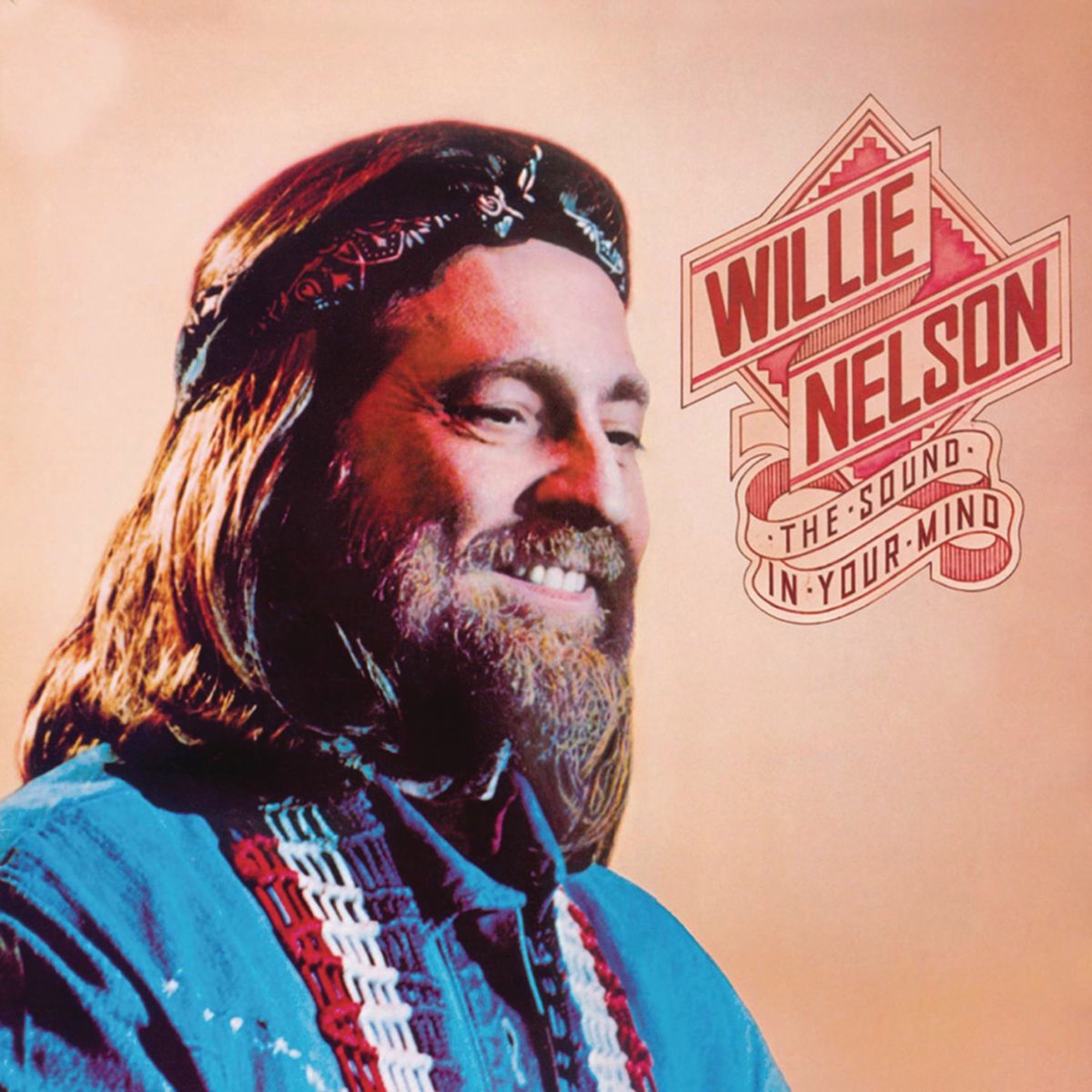

The portraits on his album covers chart the changes in Nelson’s look and outlook, from the clean-shaven chin, slicked-back hair and comfy sweater on My Own Peculiar Way (1969), to the bell-bottom jeans and shades on The Words Don’t Fit The Picture (1972), the long hair, beard and cowboy hat on Red Headed Stranger (1975) and the full-on hippy on its follow-up The Sound In Your Mind (1976).

When Nelson left Nashville, he was still making albums for RCA, releasing six between 1970 and 1972 before they parted ways. The most interesting was 1971’s Yesterday’s Wine, a concept album with a sparser production and a spiritual bent that told the story of a being that Nelson called the Perfect Man. When Nelson moved back to Texas, looking for the reasons for all that had been going wrong in his life – the fire; the two broken marriages; an industry that seemed more interested in him as a songwriter than a performing artist – he started reading the Bible and Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet. He put the questions into songs, he said, and turned the songs into prayers. RCA reportedly told him it was his “worst fucking album yet”.

In 1973 Nelson signed to Atlantic for two albums. The first, Shotgun Willie – guests included Doug Sahm and Augie Meyers from The Sir Douglas Quintet and Waylon Jennings on guitar and vocals – got good reviews and crossover coverage. The second was yet another concept, Phases And Stages, telling the story of a divorce from the point of view of both partners, the woman’s perspective on side one and the man’s on side two. Where Yesterday’s Wine, contemplating mortality, was remarkable, Phases And Stages was truly radical. No-one in country had made an album like this.

Then in 1974 Atlantic decided to close its country division. Nelson was without a label, but it turned out to be a blessing. In 1975 he signed a contract with Columbia that gave him complete creative control. He could produce himself, record with his touring band or anyone else, and no-one could change a note.

The label were eager for a new album, but Nelson needed songs. His wife Connie suggested a cowboy song called The Red Headed Stranger, which was written in the 1950s by Edith Lindeman and Carl Stutz with crooner Perry Como in mind. Nelson used to sing it on the radio show he hosted in Fort Worth in the ’50s as a lullaby to send kids to sleep. Nelson got to work on a story about a preacher on a black horse, his unfaithful wife, her lover. Songs of love and death, remorse and redemption.

Breaking the law: Willie Nelson performing with Johnny Cash, circa 1975.

TEXAS, 1975. IN DALLAS ON TOUR, NELSON TOLD his band he had an idea for an album. With downtime between shows, he asked if anyone knew any studios. Dallas-born Mickey Raphael said a place had recently opened in the suburb of Garland and he knew its engineer, Phil York.

Autumn Sound, large and modern, didn’t look like the kind of place where myths were made. But it had a state-of-the-art 24-track console, reportedly the first in Texas. Accompanied by Raphael, bassist Bee Spears, drummer Paul English, Jody Payne on guitars and mandolin, Nelson’s old friend Bucky Meadows on guitar and Willie’s sister Bobbie, Nelson accepted York’s offer of a free day to try it out. Fifty years later, Mickey Raphael remembers it well.

“We all sat in a circle,” he tells MOJO. “Willie had the notes and the words on a napkin or a torn piece of paper he would put on his lap or a music stand. We didn’t know the songs, so he would go through the song once, maybe again, we’d turn on the tape machine and play along, everyone bleeding into each other’s mikes.”

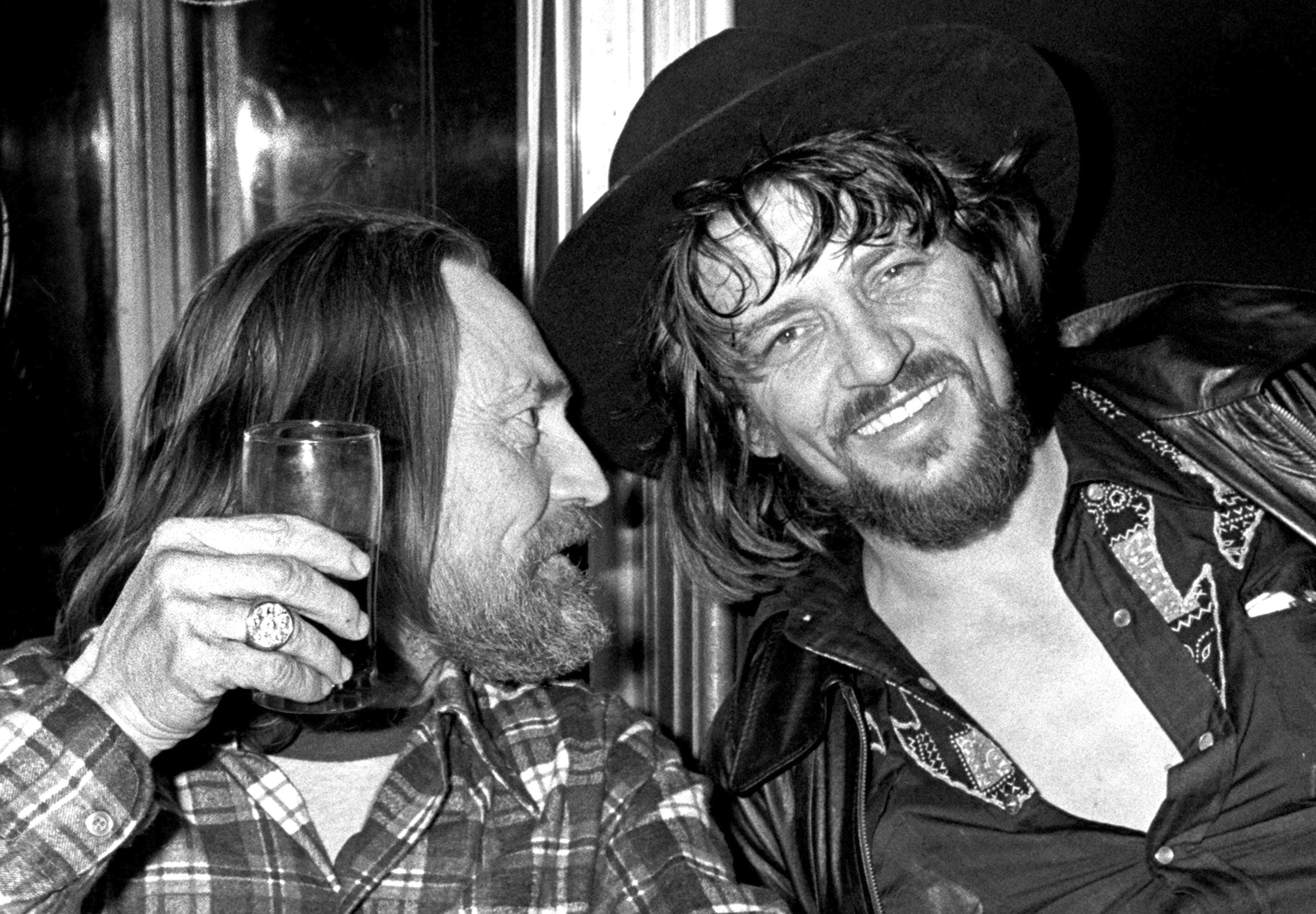

Nelson and Waylon Jennings freshen up in New York, 1978.

Nelson’s band weren’t much on rehearsing; they were playing most nights. “Everybody knows where to start and where to stop,” says Raphael, “and if nobody gets hurt during the song we’re OK.”

Besides, the production and arrangements were so basic, there was little to mess up. “We were just happy to play something new and have a chance to play on a Willie record for the first time,” Raphael adds, “because at that time road bands weren’t accepted as recording musicians.”

At the end of the day, before repairing to the Garland Holiday Inn, Nelson asked York to make a mix of the five songs they recorded and send it to him. He liked what he heard. “Because it didn’t sound like a fucking Nashville production,” says Joe Nick Patoski, the music historian and writer of 2008 bio Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. “He knew what he wanted.”

The late Phil York recalled the sessions in a radio interview. “Willie said, ‘I’m going to play this song just by myself, me and my guitar. If you can add something really good to it…?’ The drummer got up and left, the steel player got up and left. I think a couple of other people got up and left the room.”

Nelson’s band knew when not to gild a lily. “We did one take, maybe two,” recalled York. The engineer offered to smooth out a rough edge in Nelson’s vocal. Willie told him to leave it as it was.

York remembered a phone call from Columbia, asking for the Red Headed Stranger two-inch tape. Nelson asked why. To dress it up a bit for a TV show, was the answer. “Willie just said two words,” recalled York. “The first one starts with an ‘f’ and the second one starts with a ‘y’.” Then Nelson slammed down the phone.

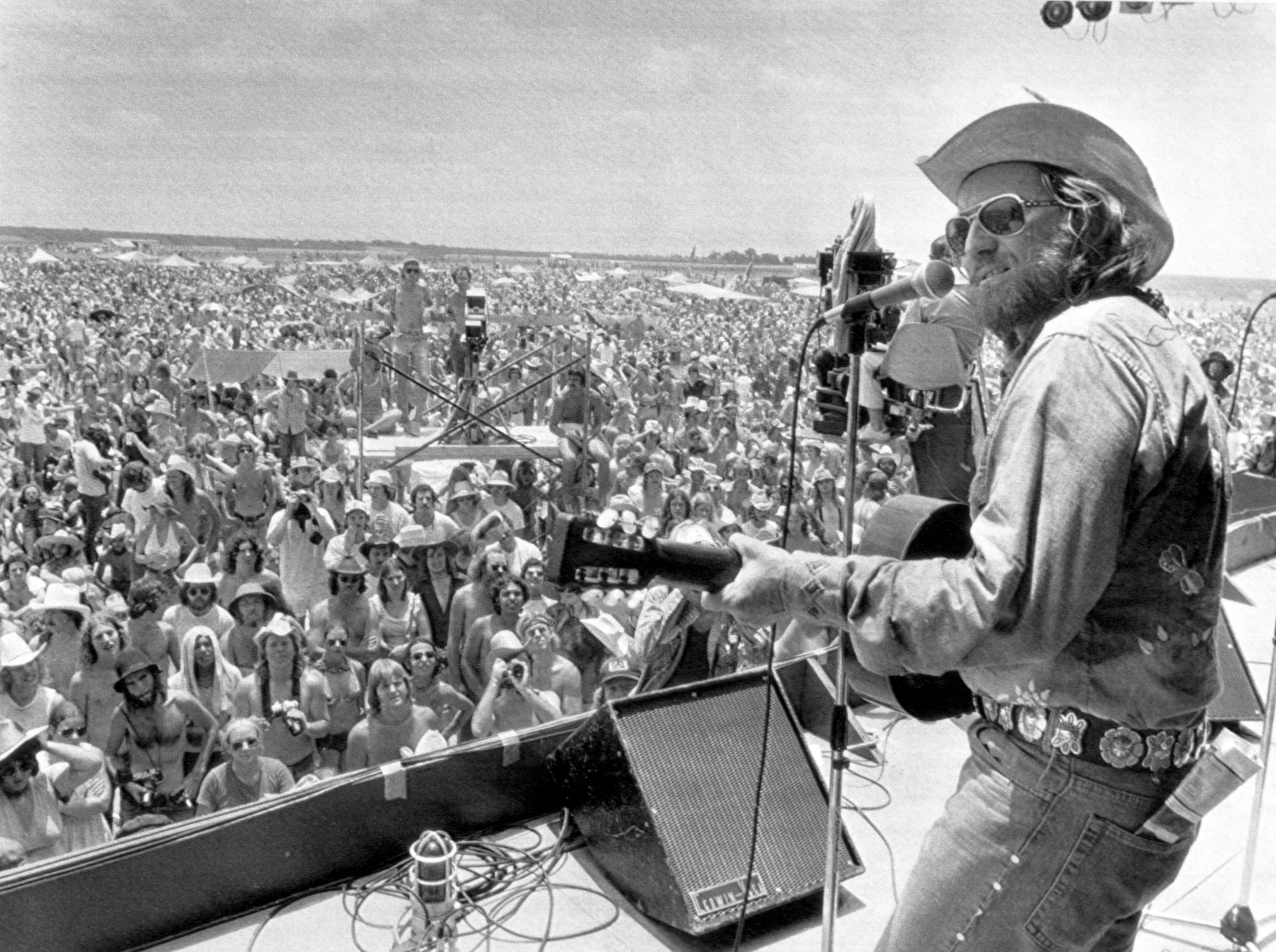

Here comes trouble: Nelson plays to 40,000 at his Fourth Of July Picnic, College Station, Texas, 1974.

In 1975, Red Headed Stranger did not sound like a country record. In many ways, it still doesn’t. A campfire recital of cowboy-story songs laced with a streak of religion, its meditative ballads – for instance, the narcotically slow version of Hank Cochran’s Can I Sleep In Your Arms – drip with solitude.

It was, and is, Nelson at his best: transported, reflective, mesmerising. “I just lean towards the ballads,” he told me in a 1998 interview, when I asked about his feel for these kinds of songs. “I just enjoy singing them. I listened to country all my life and my first chords that I learned were from playing a country song or a gospel song, so coming from that I like to say I’m country.”

Chet Flippo, the late journalist who wrote …Stranger’s linernotes, called it “so remarkable that it calls for a redefinition of the term country music. What Nelson has done is simply unclassifiable; it is the only record I have ever heard that strikes me as otherworldly.”

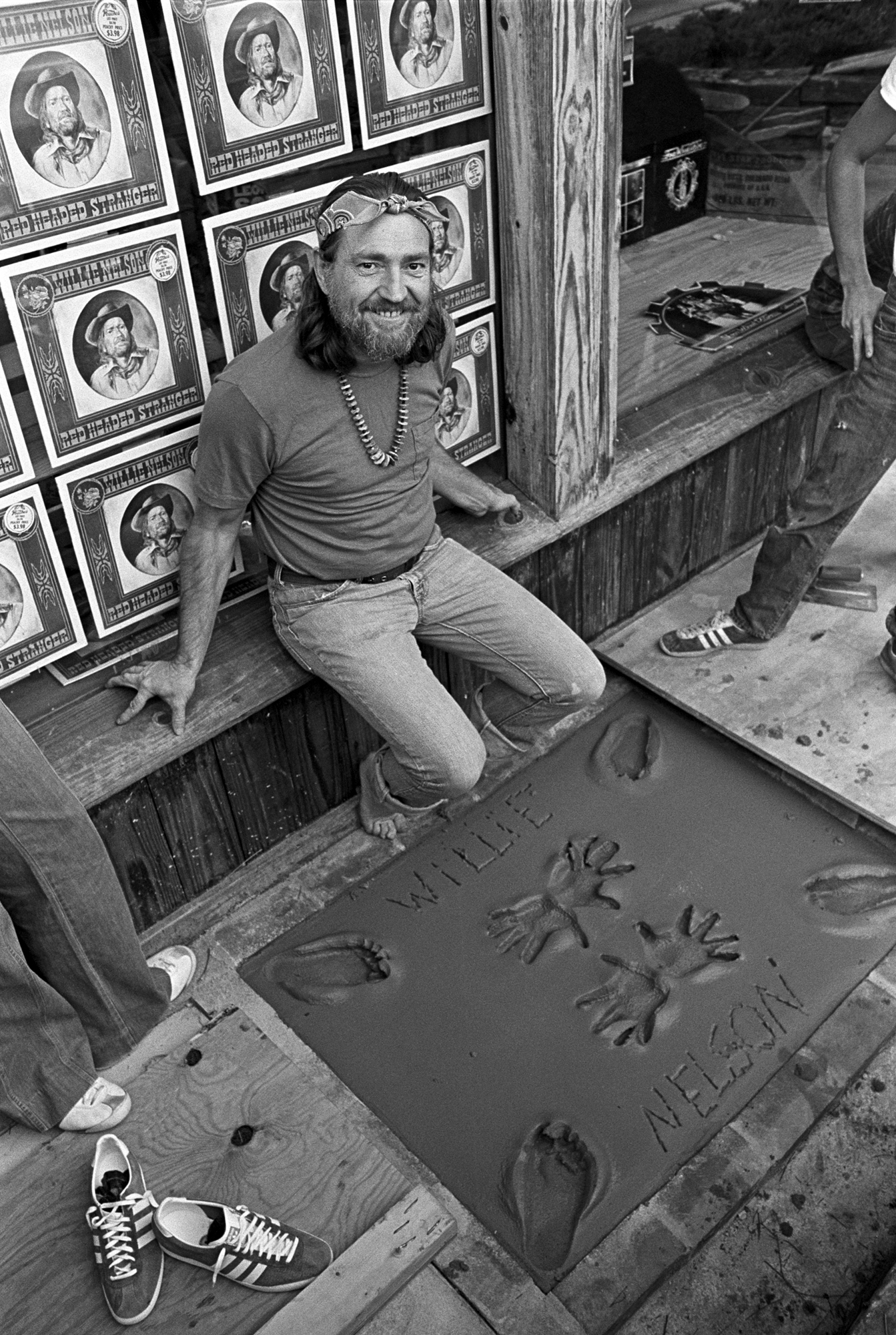

Nelson promotes Red Headed Stranger by leaving his mark at Atlanta’s Peaches Records, October 28, 1975.

1976 AND BEYOND. NELSON WAS already hot in Texas, but as his wife Connie pointed out, the hotness ended at the state line. After Red Headed Stranger that changed. “We got to travel a little more,” says Mickey Raphael. “We were playing nicer venues, we started playing theatres.”

The audiences were suddenly a little bigger and a lot younger. “It really got to be a cool thing to like Willie,” Raphael says. Shortly, they were playing major arena shows. The album was certified gold in the spring of 1976 then platinum, eventually double platinum.

“We all sat in a circle. Willie had the notes and the words of the songs on a napkin or a torn piece of paper.”

Mickey Raphael

Nelson was on the cover of Rolling Stone. The New York Times called him “the acknowledged leader of country music’s left wing”. Newsweek called him “the King Of Country” – Roy Acuff’s old sobriquet. Columbia gave Nelson his own label, Lone Star, and left him to his own devices. He kept on making records the way he wanted to, among them his 1978 classic Stardust.

As to the Outlaw Country movement, Nelson likely did not sire it – bands including The Flatlanders were already merging country and rock – but he brought it to the mainstream press. His old pal and fellow traveller Waylon Jennings kept that pot well-stirred too. Jennings won the rights to produce his own records from RCA in 1972, the year Nelson’s contract with that label expired. Jennings’ 1973 album Honky Tonk Heroes was an Outlaw-friendly blend of rock and country, while 1976’s Are You Ready For The Country, featuring several rock covers, topped the country charts and made the pop Top 40 too. That same year RCA released a Jennings compilation, Wanted! The Outlaws, that featured Nelson on four of the tracks: another country Number 1. The two of them released an album of duets in 1978, Waylon & Willie, that topped the country chart and stayed there for 10 weeks.

Nelson and band, including (above far right) Mickey Raphael, Saturday Night Live, December 10, 1977.

“Willie and Waylon were kindred spirits,” says Mickey Raphael. “They would write together, we would do some gigs with him. Waylon would show up sometimes and sit in on our gigs and Willie would do the same with Waylon. They were cut from the same cloth.”

Nelson’s biographer Patoski argues Austin played a big part in the story. The city’s hippies and students endorsed Nelson’s rebellion. The singer said he liked how the hippies dressed as they pleased, did what they wanted and supported the music he played. There was support too, from radio stations who regarded ex-DJ Willie as one of them. They jumped on Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain, laying the ground for the album’s success.

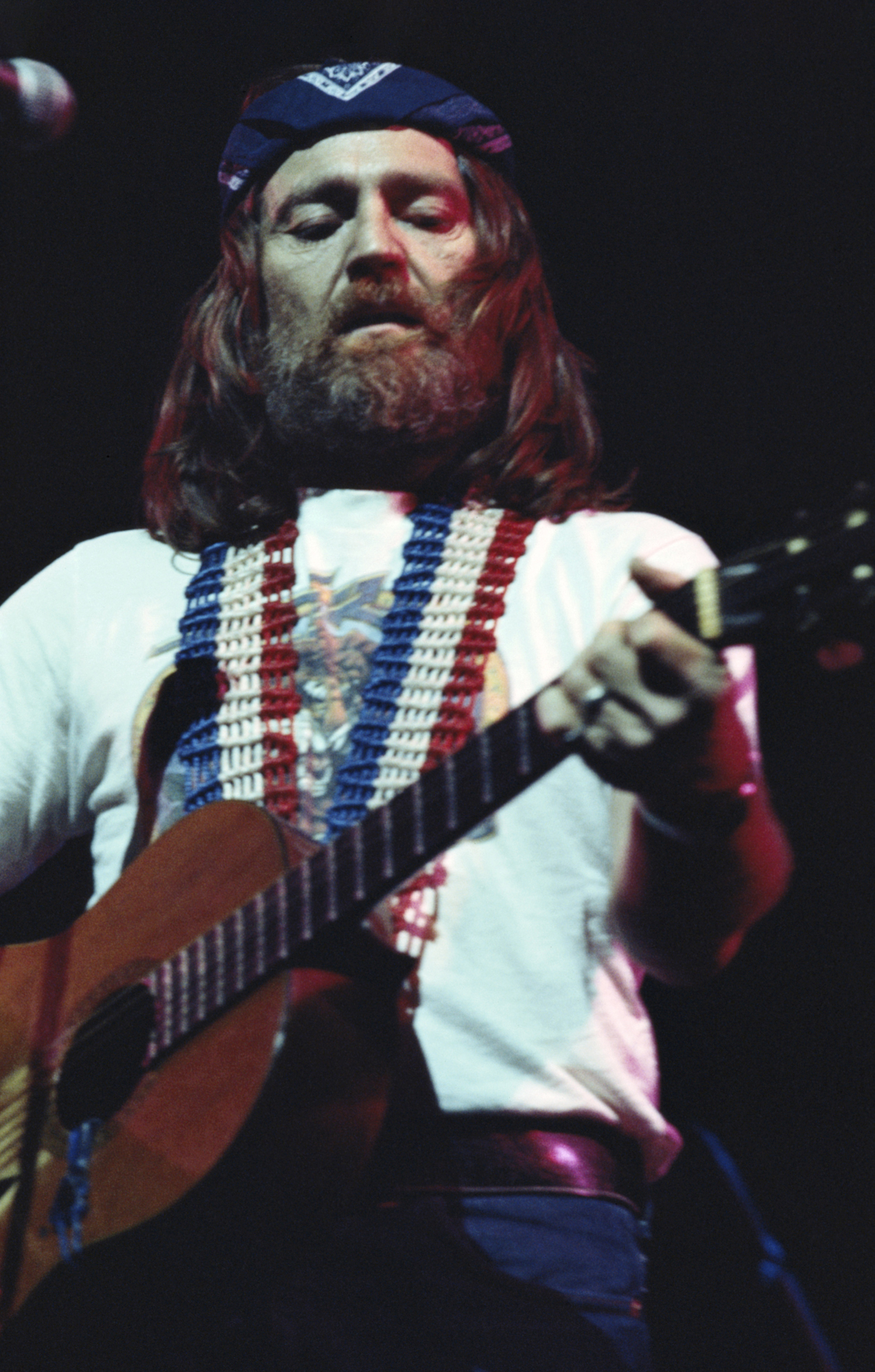

Nelson at Hammersmith Odeon, 1977.

“I think about him writing songs as a kid, as a teenager, as a young man,” says Patoski, “always trying to write songs, and how it must have been flattering, when he sold songs for $50, that somebody wanted to pay him. As a kid Nelson loved westerns and cowboy stories. Red Headed Stranger was as much a great cowboy story as a culmination of who he was. His story was wanting something bad, and finally getting it.”

Willie gives President Carter a bowl in the Oval Office, 1979.

Red Headed Stranger was Nelson’s vindication, but it also became his totem – encouragement to blaze his own trail, come what may.

“I never really worried too much about what people thought,” he told me in an interview for MOJO in 2012. “That has been a positive and a negative for me along the way. But either way, I think, Well I’ll do what I do and they can either like it or not.”

Estate of David Gahr/Getty Images; Getty (7), Alamy; Getty (5)