Mojo

FEATURE

A Right Pair

Two halves of one brain, John Lennon and Paul McCartney formed the most extraordinary and intimate musical partnership of the rock era. In this extract from a new book that probes their bond through the medium of their songs, Ian Leslie discovers how one of them, Sgt. Pepper’s Getting Better, was a case of Paul reaching out to John, changed but also estranged by his new love… LSD.

Words: Ian Leslie

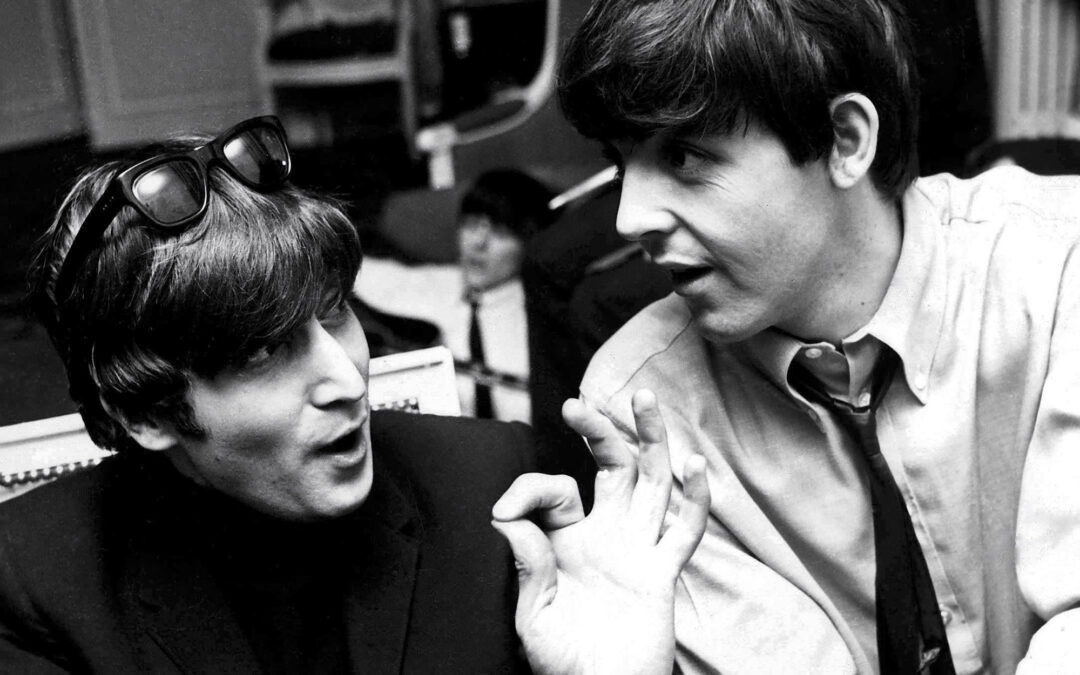

From me to you: John Lennon and Paul McCartney get better and better, Paris, 1964.

ON THE EVENING OF March 21, 1967, three of The Beatles were at Abbey Road, recording backing vocals for a song called Getting Better. John, Paul and George were gathered around a microphone. After a few run-throughs, John took out a silver snuff box he kept his pills in and began poking around in it, searching for an upper to keep him going. Soon afterwards, he faltered and stopped in the middle of a line. He looked up to George Martin in the control room. “George, I’m not feeling too good,” he said. “I’m not focusing on me.”

Martin paused the session and took John up to the roof for some fresh air. The other Beatles stayed behind. But as McCartney and Harrison discussed what might be the matter with John, they figured out that he had probably taken a tab of LSD by accident – and that maybe standing on the top of a building wasn’t the best place for him. They rushed up the stairs, hoping that John did not decide to see if he could fly before they got there. As it turned out, he was OK. Still, work was halted for the night, and the band dispersed.

Paul and John stayed together. With the drug exerting its effects on his brain, John didn’t want to travel back to his home in Surrey. He and Paul headed for Paul’s house on Cavendish Avenue, a short drive from the studio. Once there, Paul decided he would take some LSD himself. Although he had tried acid for the first time in late 1965, that was with other friends. Now he wanted to “get with John”, as he later put it to Martin, who interpreted it to mean “to be with him in his misery and fear”. McCartney told Barry Miles: “I thought… maybe this is the moment. It’s been coming for a long time.”

That night, John and Paul did something that the two of them practised quite a few times during this period: they gazed intensely into each other’s eyes. They liked to put their faces close together and stare, unblinking, until they felt themselves dissolving into each other, almost obliterating any sense of themselves as distinct individuals. “There’s something disturbing about it,” recalled McCartney, much later, in his understated way. “You ask yourself, How do you come back from it? How do you then lead a normal life after that? And the answer is, you don’t.” The Beatles’ publicist and friend Derek Taylor recalled Paul enthusing about LSD: “We had this fantastic thing… Incredible, really, just looked into each other’s eyes… Like, just staring and then saying, ‘I know, man,’ and then laughing.”

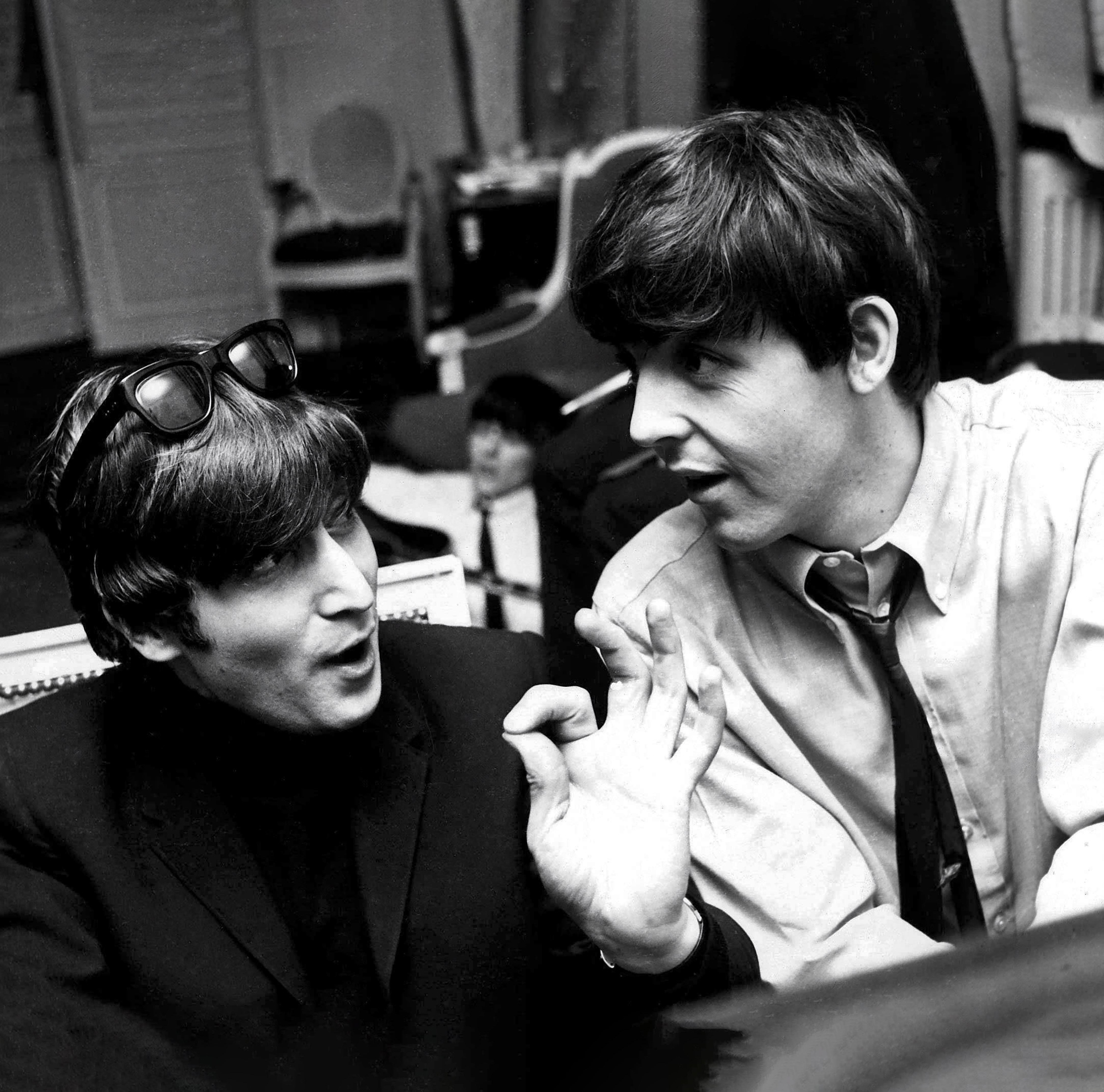

Lennon and McCartney working on Sgt. Pepper, Abbey Road, March 1967

“We had this fantastic thing… Just looked into each other’s eyes… just staring and then saying, ‘I know, man,’ and then laughing.”

Paul McCartney

JOHN AND PAUL WERE getting towards the end of their work on what had become the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. They were working on what they called “slog songs”. “The last four songs of an album are usually pure slog,” Paul told Hunter Davies, around this time. “If we need four more we just have to get down and do them. They’re not necessarily worse than ones done out of imagination. They’re often better, because by that stage in an LP we know what sort of songs we want.”

By songs “done out of imagination”, Paul meant those that one or the other of them already had floating around before sessions on an album began – like Eleanor Rigby, Tomorrow Never Knows or A Day In The Life. Those songs arrived unbidden and were sometimes fragmentary or unfinished. Once the group had realised those ones in the studio, they usually needed a few more, and often had a tight deadline. So John and Paul would meet up, usually around two in the afternoon, and knock out the slog songs.

It was like the difference between letting inspiration strike and trying very hard to have a new idea. On that basis, you might expect the slog songs to sound more formulaic and less interesting. But because John and Paul were so relaxed in each other’s company, they were able to tap into each other’s unconscious and find surprises there. In 1967, the journalist Hunter Davies got as close as any outsider did to witnessing this process. He was at McCartney’s house as John and Paul worked on a song for Ringo. They had composed the melody the day before. They had a title, too: With A Little Help From My Friends. Davies describes the two of them in a seemingly aimless, almost trance-like state. They would “bang away” artlessly on guitars, or Paul would sit at the piano. They’d throw out musical and lyrical phrases until something that one of them did or said snagged, at which point the other would “pluck it out of a mass of noises and try it himself”.

As Davies watches, they land on the idea of asking a question at the start of each verse. At this point Cynthia Lennon turns up with one of their old Liverpool friends, Terry Doran. Cynthia and Terry sit down, chat quietly, suggest lines when invited to and read out the horoscope, while Paul and John carry on doodling. Paul suddenly starts to play Can’t Buy Me Love. John joins in, “singing it very loudly, laughing and shouting”. Paul plays Tequila at the piano, and they go crazy again. “Remember in Germany?” says John. “We used to shout out anything.” John and Paul play through their song but with John shouting random words between the lines: “knickers”, “Hitler”, “tit”, “Duke of Edinburgh”. It’s the kind of moment familiar to anyone who has watched Get Back. This period of boisterous play stops as soon as it began. They return to the song, now very focused, and speaking softly. John finds just the right words to make a line he has been working on scan. Paul nods, says, “Yes, that will do,” and writes down the finished verse on notepaper.

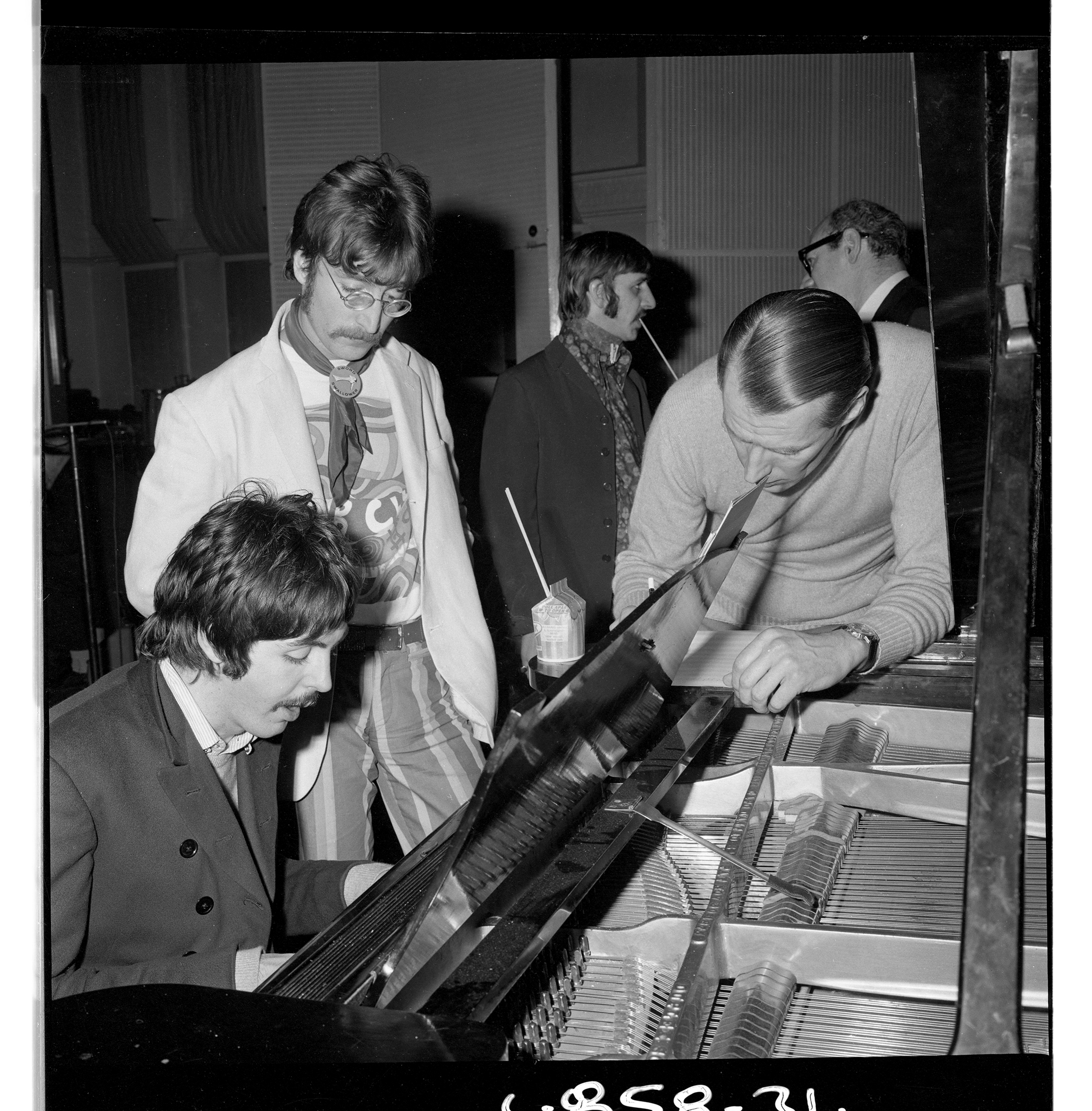

The Fabs with Ringo stand-in Jimmie Nicol, whose catchphrase was “it’s getting better”.

DAVIES WAS ALSO AROUND to see how Getting Better came into being. McCartney had been at home with time to kill. John was meant to be coming over to work on new songs, but he was late and it was a nice day, so Paul picked up Martha, the sheepdog he had acquired the previous summer, put her in his Mini Cooper and drove to Primrose Hill. As Martha frolicked in the park and the sun came out for the first time in a while, Paul thought, “It’s getting better,” and smiled. The phrase reminded him of something Jimmie Nicol used to say. Nicol was the drummer who joined the band for a few weeks in 1964 when Ringo fell ill. Whenever one of the Beatles asked Nicol how he was finding it, he’d reply, “It’s getting better.” The Beatles found this hilarious.

When John arrived at Cavendish Avenue later that afternoon, Paul said, “Let’s do a song called Getting Better.” They began strumming and improvising and larking around until a song began to form. “You’ve got to admit,” said Paul, after a while, “it is getting better” – and John started to sing that. The two of them kept going like this until two in the morning, stopping only for a fry-up, as a succession of visitors who had made appointments to see Paul were left waiting or sent away. Into this song, initiated by Paul, John poured a stream of reflections on his own life: on the anger he had carried around with him as a teenager and younger man; on the emotional and physical abuse he had inflicted on women. Since the tone of the song is light-hearted, the heaviness of the final verse is often missed.

The evening after this session, John and Paul went to the studio. Paul played Getting Better on a piano for George and Ringo. The group sat around and discussed what the song should sound like, before dispersing to noodle on their instruments, trying out bits and pieces to play. Paul joined Ringo at the drums and helped him work out his part. After a couple of hours, they were ready to record the backing track. George Martin took his position in the control room. The Beatles ran through seven takes, with Paul directing the group (“Once more”; “More drums”; “Less bass”). By midnight they had a satisfactory version. Twelve days later, they recorded the lead and backing vocals (this was the session interrupted by John’s LSD-induced freak-out). Two days after that, reported Hunter Davies, they were back in the studio to redo the vocals, finishing when “they’d got it at least to a stage which didn’t make them unhappy”.

People who knew John commented on a change in his personality that took place in 1966 and 1967, roughly coinciding with his use of pot and LSD. In early 1968, Cynthia told Hunter Davies that John was quieter and more tolerant than he used to be. His old schoolmate Pete Shotton also noticed a distinct softening of John’s personality: the ‘cripple’ impersonations stopped, the sarcasm receded. He was no longer drinking himself into oblivion and rage. His songwriting moved past the Sturm und Drang of love betrayed and spurned. He became calmer, nicer and more childlike. He even started hugging people. “This is the new thing,” John said, on hugging a friend he hadn’t seen in a while. “You hug your friends when you meet them, and show them you’re glad to see them.” He also stopped worrying about McCartney taking leadership of the group. As Lennon relaxed, McCartney became even more driven. Although Paul had now taken LSD with John, his drug of choice during the Pepper sessions was cocaine. In the studio, after the others had clocked off, he would work through the night, crafting his bass lines, obsessing over every detail of each track.

John’s drug-enabled placidity came at a cost. He was taking acid frequently now, sometimes with a group of hangers-on that he would invite back to Kenwood after a night out in the clubs. Cynthia and Julian got used to strangers in the house. “They’d wander round, glassy-eyed, crash out on the sofas, beds and floors, then eat whatever they could find in the kitchen,” Cynthia wrote in her memoir. “John was an essentially private man, but under the influence of drugs he was vulnerable to anyone and everyone who wanted to take advantage of him.” John’s use of LSD put an ever-greater distance between him and Cynthia. In the spring of 1967, he invited Pete Shotton to move into Kenwood, primarily so that he would have someone to take it with.

The first time they took it together was at Julian’s fourth birthday party. After that, John would bring a mug of tea and a tab of acid to Shotton’s room every morning.

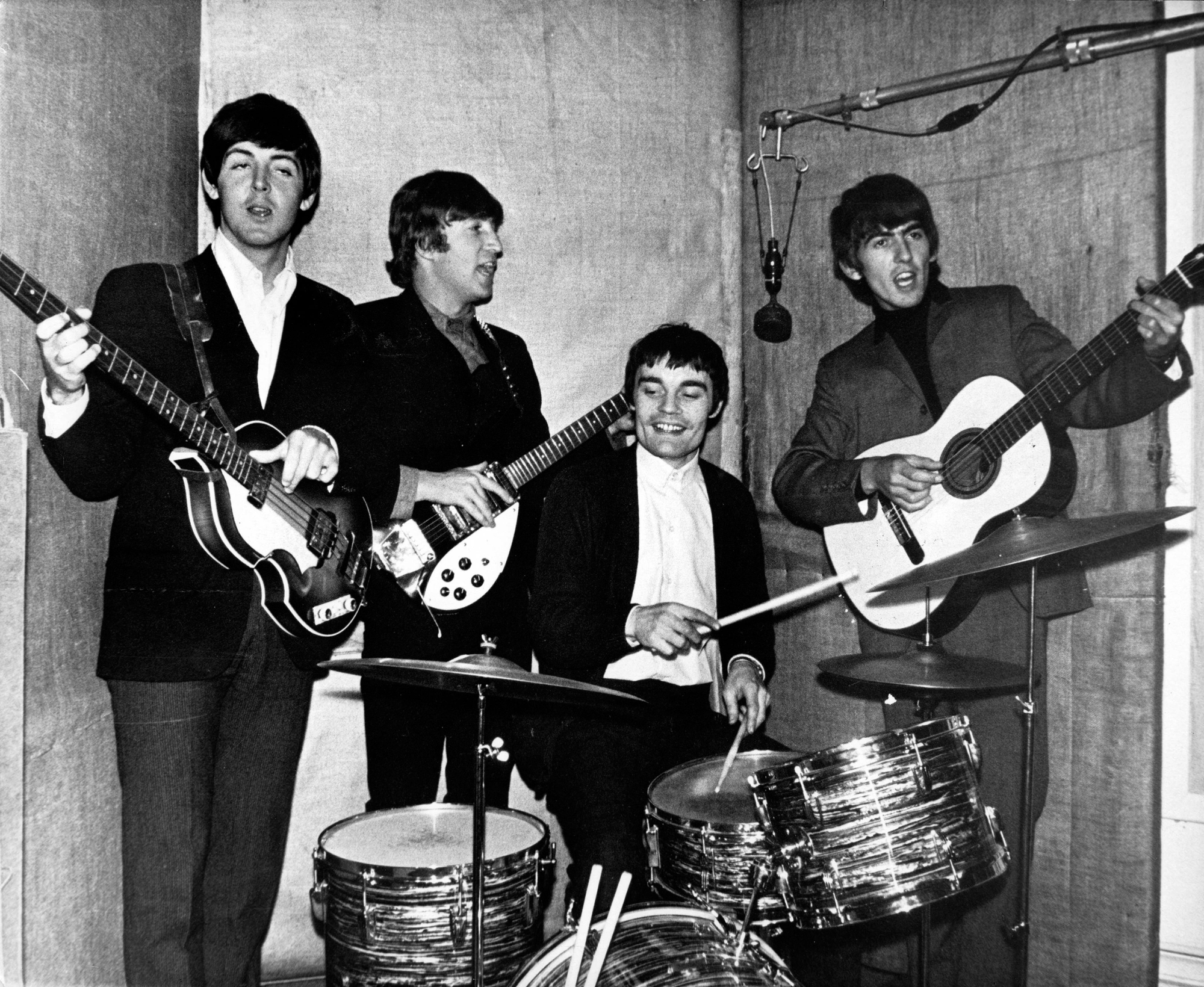

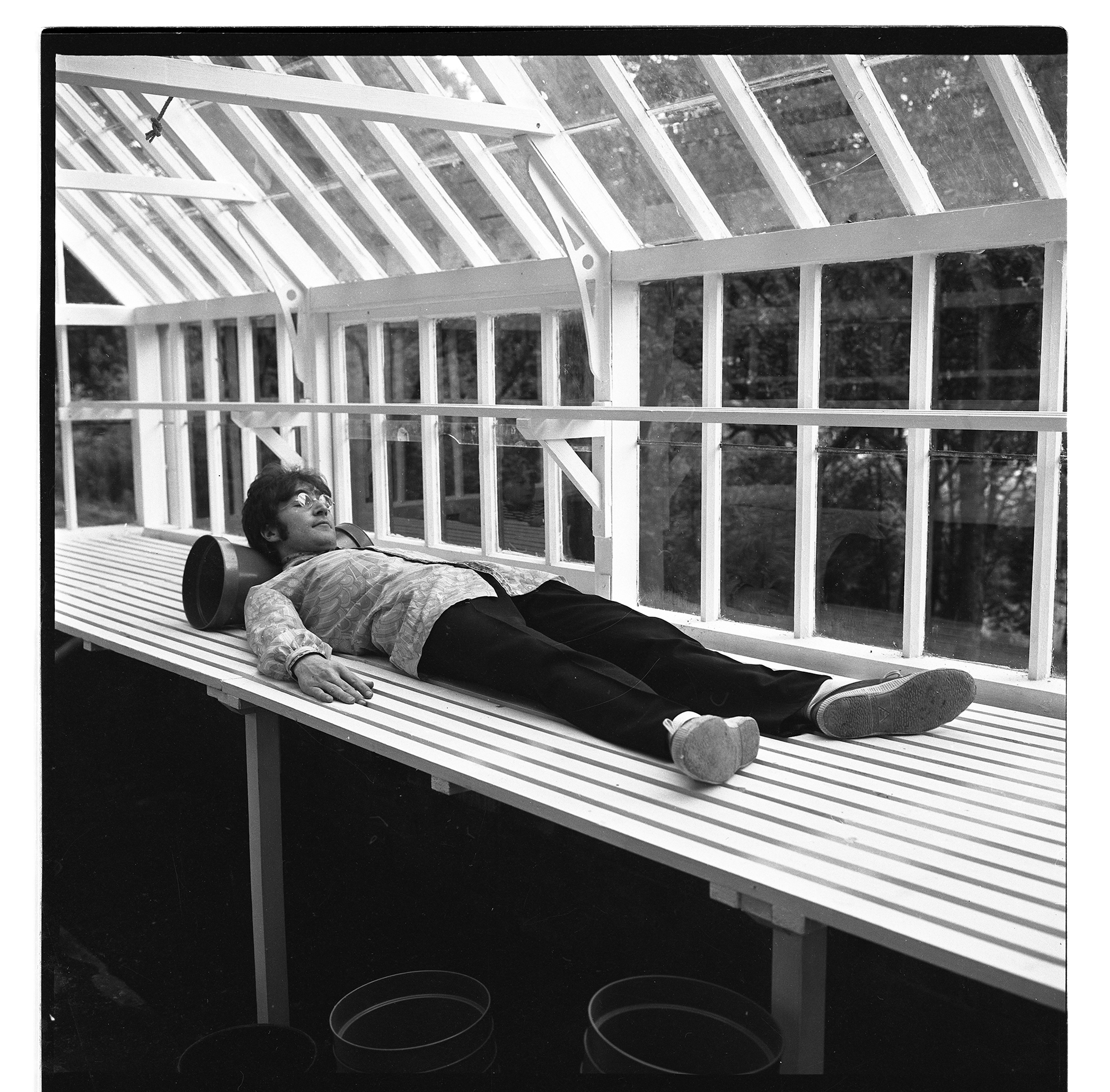

Lennon surrenders to the void, Kenwood, Surrey, 1967

Not surprisingly, John’s productivity suffered. He had never found it so hard to create new songs. Other than A Day In The Life, only three of the songs on Sgt. Pepper were initiated by him: Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite! and Good Morning Good Morning. Even on those, McCartney was the midwife. Although John claimed Kite as his, McCartney remembers being at John’s house, pointing to the circus poster that inspired it and helping John turn its copy into lyrics. Paul co-wrote Lucy, too. The number of co-created Lennon and McCartney songs on Pepper (at least six feature significant writing contributions from both of them) is testament to their closeness at this time, but also to how much Paul was now having to coax songs out of his partner.

Nobody, not even John, believed more in John’s talents than Paul, or was more deeply invested in him making the most of them. McCartney also wanted his friend to be happy. He could see that John was calmer than he had been. He could also see that John was unmoored. When John wasn’t working, he was tripping. Left to drift aimlessly, he might lose himself altogether. By choosing to take LSD with him, Paul was giving John a chance to take the upper hand in at least one aspect of their relationship – to play the role of psychedelic guide – while ensuring that the drug’s mind-expanding properties were channelled into creativity.

In Getting Better, Paul nudged John into creating a kind of self-help narrative of his own life, sung, paradoxically, by Paul. The narrative is commented on, waspishly, by John (“fool, you fool”), playing a Greek chorus in the drama of his own maturation. The singer has been helped to put aside the self-loathing and rage of his youth by, well, someone. His realisation is arrived at grudgingly, as something he has to admit, just as you might acknowledge a friend who often annoys you but who is busy saving you from yourself.

John & Paul: A Love Story In Songs by Ian Leslie is published by Faber & Faber on March 27. £25 hardback, £14.99 ebook.