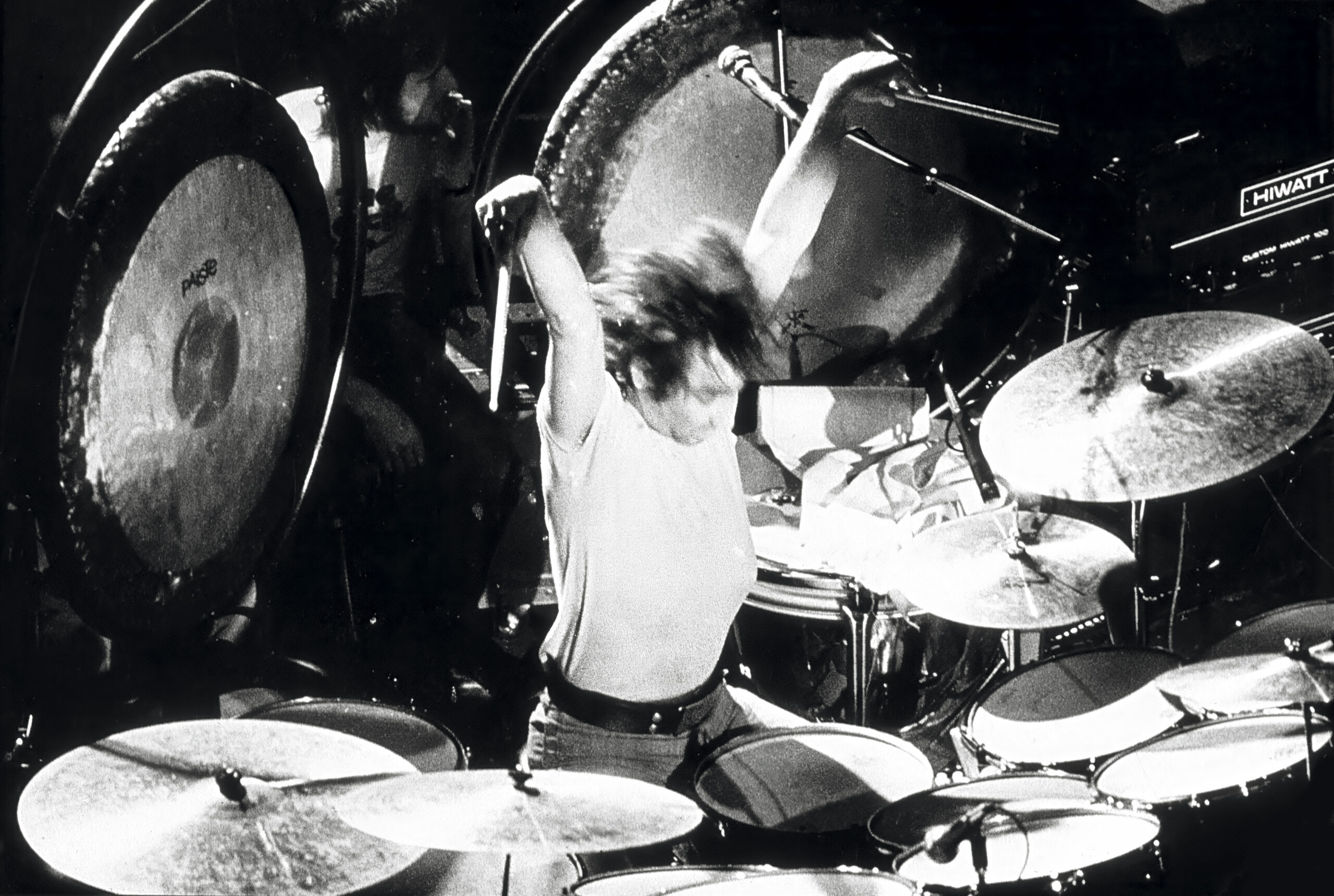

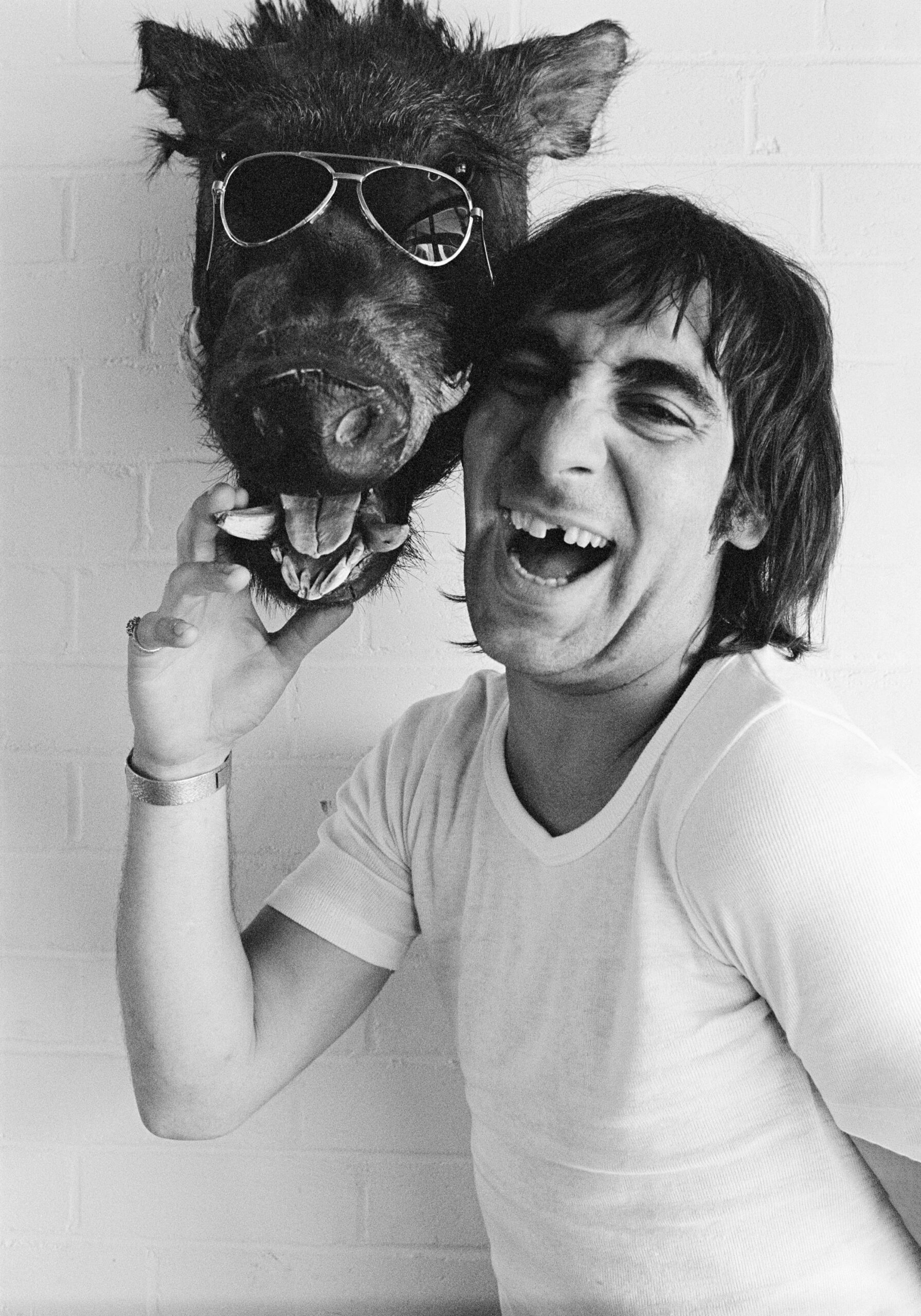

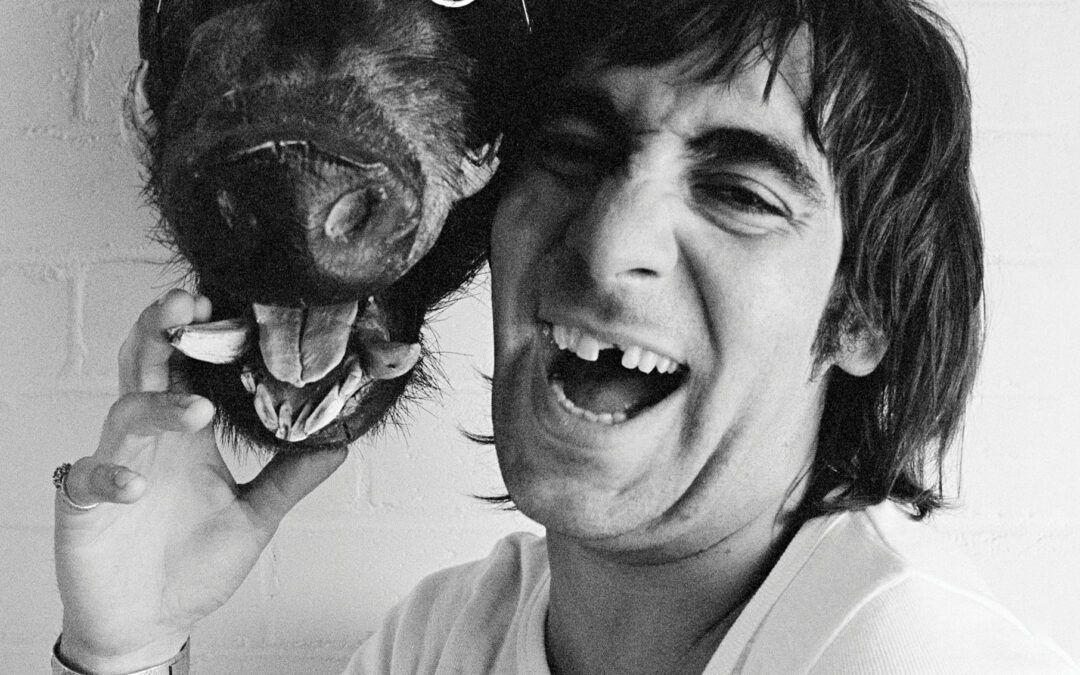

Animal magic: Keith Moon cuts loose in 1973.

THE CIRCUMSTANCES LEADING UP TO THE recording of Who Are You – fatefully the group’s last album with their pyrotechnic, if problematic drummer – found a tired and disillusioned band flying in the face of punky musical fashions. As evidenced by a new and vastly expanded 89-track box set reissue of the album – featuring demos, rehearsals, live performances, rejected Glyn Johns mixes and new Steven Wilson Atmos remixes – it saw Townshend double down on the synth experiments he’d first dabbled in circa 1971’s Who’s Next, and lean into FM rock, while lyrically blaring his creative torment in Guitar And Pen and his music biz disenchantment in the cynical New Song.

If Townshend was troubled, then Moon seemed lost. When the ’75-’76 tour was over, he stayed behind in Los Angeles, mainly to escape Britain’s 83 per cent tax for high earners. “They’re driving out all those people who make the money,” Moon moaned to NME, while fretting about the instability of music careers. “What so many people fail to appreciate,” he stressed, “is that in many cases a person may only ever have a single opportunity to make it.”

During this period, a frequent visitor to Moon’s Malibu beach house was his young godson, Zak Starkey, son of Ringo Starr.

Beach boys: [From left] Ringo Starr, Zak Starkey and Moon on the beach in Malibu.

“My dad used to send me to stay with Keith in Malibu quite regularly for the weekend,” Starkey told MOJO last year, “…in retrospect (laughs)… not the greatest babysitter ever, right?

“We sat and drank beer together, even though I was 10 or 11. He got me into The Beach Boys, and he talked about surfing and girls. It turns out he’d only ever been surfing once, and he nearly drowned, and he never did it again.”

All the while, not playing drums and largely idle, Moon’s extreme imbibing only worsened during his time in California, particularly in an era where the LA music scene was characterised by wild overindulgence. “It was settling into a ‘nothing to do’ lifestyle that messed him up,” reckoned Entwistle. “He had a pill for every time of the day.”

In one moment of desperation, the drummer’s girlfriend, Swedish model Annette Walter-Lax, sought the help of the couple’s neighbour in Malibu, actor Larry Hagman, who had shared the screen with Moon – typecast as feral drummer J.D. Clover – in 1974 rise-and-fall rock film Stardust (reprising his role from 1973’s That’ll Be The Day). Moon duly checked into a Cedars-Sinai treatment facility for three days in February 1977, in another failed

attempt to clean up.

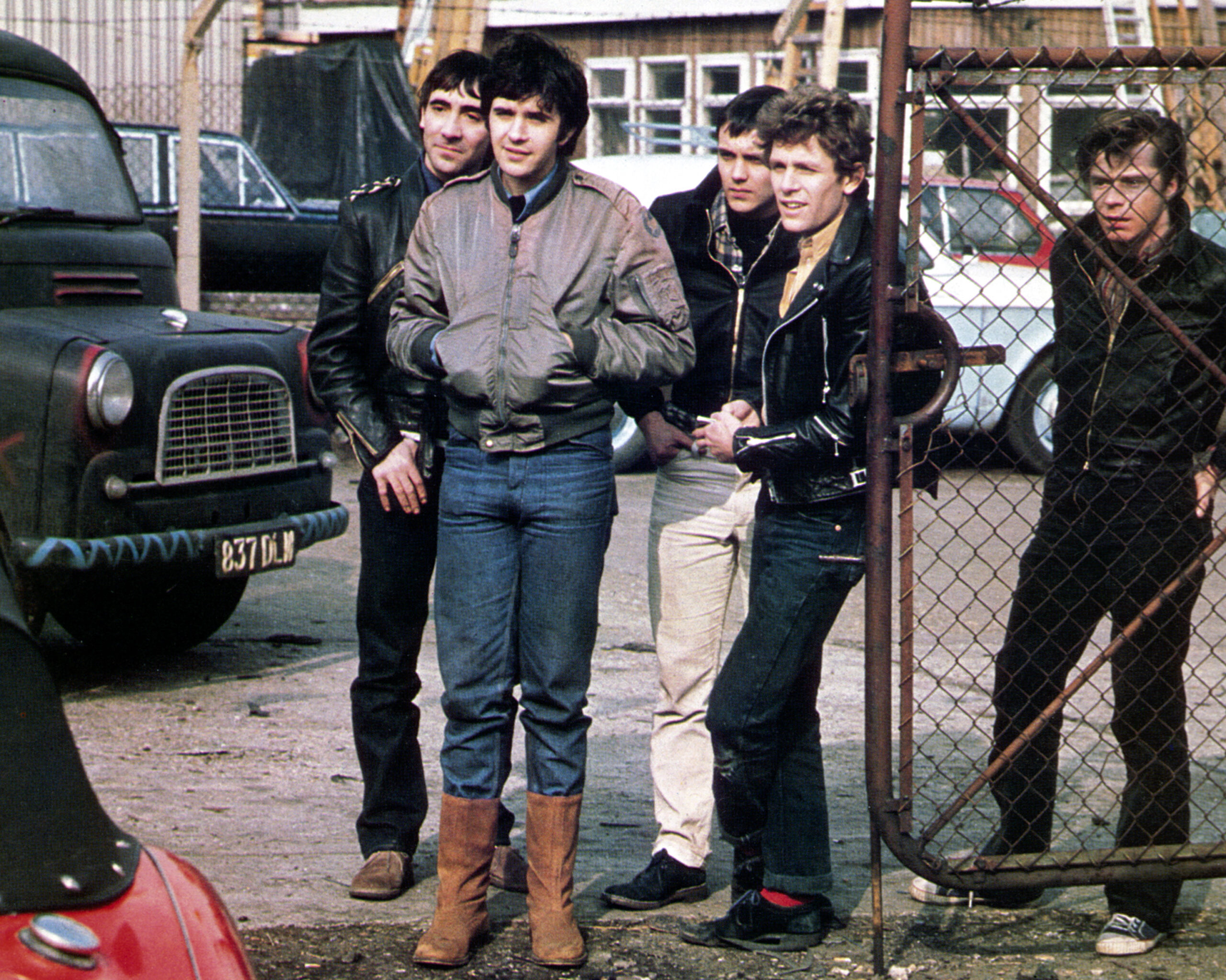

Lucky for some: Moon as ‘J.D. Clover’ alongside David Essex, Karl Howman and Billy Fury in That’ll Be The Day.

An ongoing film career was clearly in the drummer’s plans, leading to perhaps the strangest movie cameo of his brief and chequered screen career (which had included playing a harpist nun in Frank Zappa’s 1971 mind-boggler 200 Motels). Appearing alongside octogenarian film star Mae West – and a supporting cast that included Tony Curtis, Ringo Starr and Alice Cooper – Moon hammed it up magnificently as a camp fashion designer.

A different movie crew arrived at the Malibu beach house in August ’77 to film interstitial scenes for director Jeff Stein’s mosaic Who documentary, The Kids Are Alright. Interviewed in tandem with his booze buddy Ringo (slurring throughout), a bearded Moon was totally wired, and sharply funny.

Canvassing his opinions on the other Who members, Starr cheekily enquired of his relationship with Daltrey, “What about the little singer? What’s your opinion of him?”

“Well… I think he does a damn good job out there,” Moon averred, before praising the frontman’s mike-whirling talents. “He manages to revolve it so fast that when people throw things, he gets a sort of desiccated egg and a sliced tomato. At the end of the night I have a salad mixed. I just sprinkle some salt and Italian seasoning on it.”

Back in England, the other members of The Who were not seeing the funny side and grew increasingly concerned about their self-exiled drummer. Townshend flew to LA in autumn ’77 and convinced Moon to return to the UK and rejoin the band for their next venture. Keith didn’t need much persuasion.

“I was really drifting away with no direction,” he subsequently confessed. “I’d try to do things and get involved with projects. But nothing ever came close to the feeling I get when I’m working with the guys.”

See me: Moon during the filming of Tommy, 1974.

HAVING BRIEFLY RECONVENED in July 1977 at Shepperton Studios in Surrey – where The Who had leased two enormous sound stages and an office building to use as the nerve centre of their music and film operations – the future of the band looked altogether positive.

Performing for the benefit of Jeff Stein’s cameras, they powered through some of their standards and indulged in semi-piss-taking renditions of The Beatles’ I Saw Her Standing There and The Beach Boys’ Barbara Ann, a sweaty Moon attempting falsetto lead on the latter from behind his kit.

And yet, two months later, recording what would become Who Are You, the drummer was in worryingly bad shape. Ahead of preliminary sessions, beginning in September ’77 at the band’s Ramport Studios in Battersea, the drummer had been suffering from seizures due to sudden alcohol withdrawal.

Nonetheless, on day one, he appeared to be back to his old devilish self, likely since he’d reacquainted himself with the brandy bottle and other familiar substances. Firstly, he took a strange dislike to a new message board that had been bought for the studio and set it alight. Next, he tested out the drum sound that Jon Astley – engineering for producer Glyn Johns – had spent the previous day perfecting. Once Astley declared himself satisfied with the stereo balance, as later he recalled, Moon “stood up and walked through the bloody kit”, wrecking the set-up.

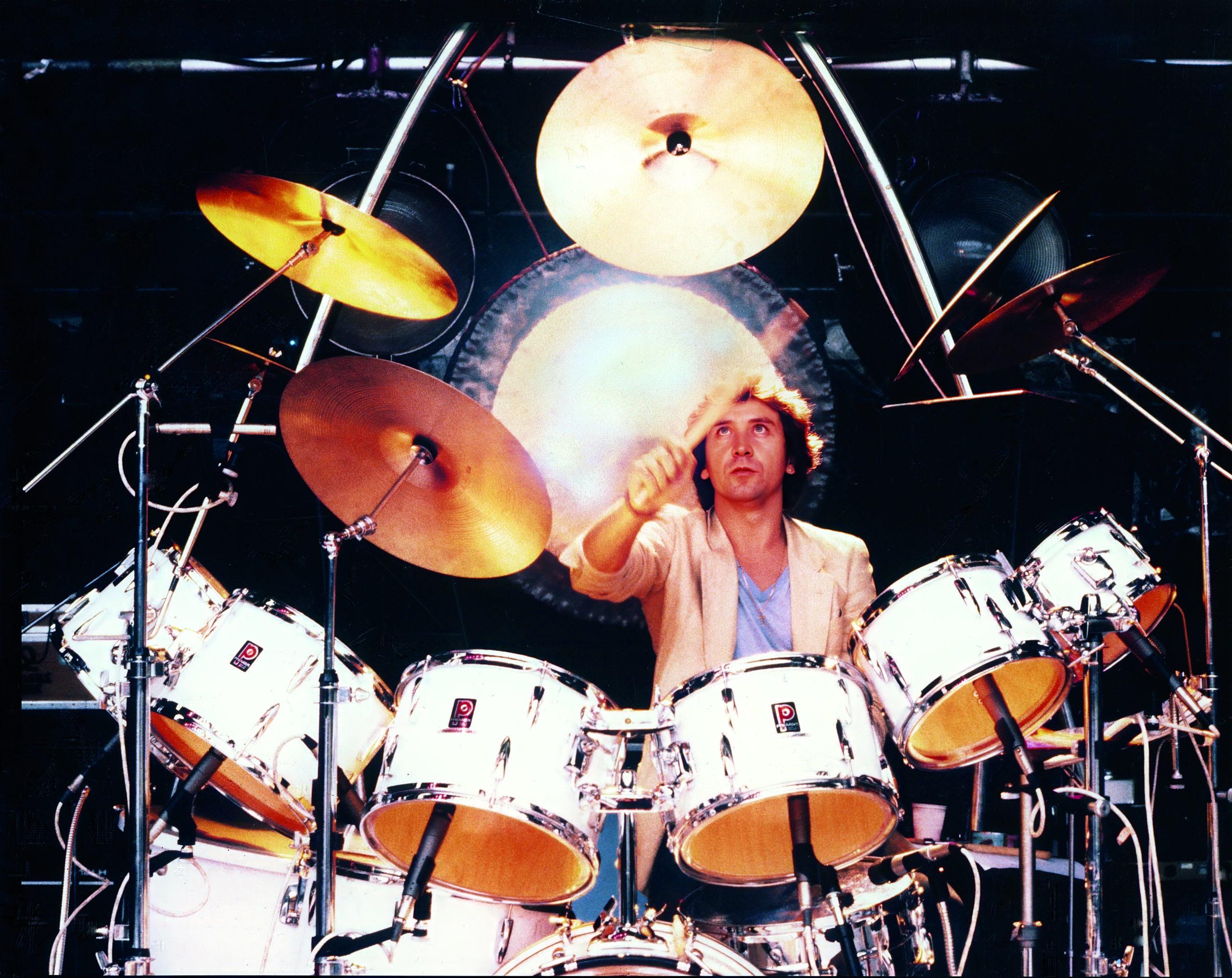

Such unhinged antics were easier to tolerate when Moon was on top musicianly form. But when the tapes rolled, it quickly became apparent that the drummer’s timing was all over the place. Part of the problem was that Moon was being pushed by the others to lay down straighter beats (at the time in vogue on US rock radio) that inhibited his inherently frenetic style.

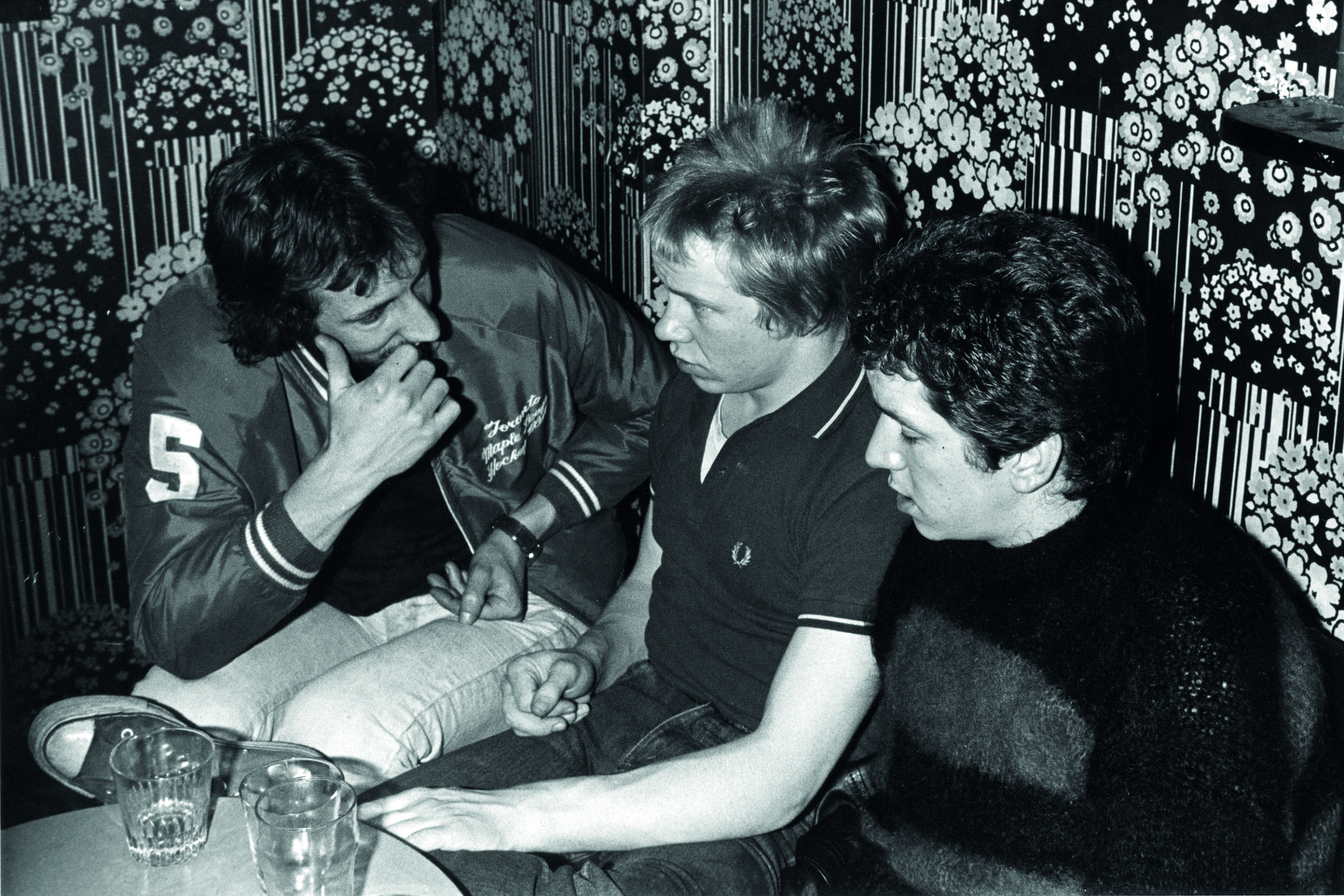

Who’s fooling who: Pete Townshend meets Sex Pistols Paul Cook and Steve Jones at the Speakeasy Club, London, 1978.

Given other current musical fashions, it might have been a better idea to allow Moon completely off the leash. The drummer, like the rest of The Who, had a complicated attitude towards punk, which he and his bandmates had clearly inspired. Paul McCartney later told MOJO’s Paul Du Noyer, “I know people like Keith Moon were not so much threatened, as just pissed off, that the people who were emulating his drum style were calling him a boring old fart.”

Roger Daltrey was characteristically belligerent about the new upstarts, deciding, “Fuck you, you can’t out-punk The Who.” Pete Townshend reacted by drinking harder, one night meeting Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols at the Speakeasy club in London’s West End, ranting at the pair about the financial unfairness of the music business and then conking out in a Soho doorway, before being woken by a policeman – thus finding inspiration for the verses of the work-in-progress Who Are You.

Moon, meanwhile, taunted the punks, turning up at the Vortex on Wardour Street in his Rolls-Royce and conspicuously playing the big spender at the bar. “They threatened Keith,” remembered Townshend of the drummer’s fellow club-goers, “and he laughed at them, inviting them to come out and ride around in his car. I wasn’t so brave.”

“I was really drifting away with no direction. Nothing came close to the feeling I get when I’m working with the guys.”

ALTHOUGH, IN TRUTH, ALBEIT in private, The Who could be just as lairy as the punks. In October 1977, tempers erupted in the studio when Glyn Johns played Daltrey synthesized string parts that had been added to two tracks, Sister Disco and Had Enough. The singer bluntly told the producer he thought the results were “crap”. An argument broke out and the two spilled into a corridor. Johns apparently called Daltrey “a little cunt”. The singer responded by headbutting him. Johns stormed out of the studio and refused to work with The Who’s frontman for the remainder of the record (with Jon Astley assuming a co-producer role).

The turbulence continued into December. On the night of the 15th, at the Gaumont State Cinema in Kilburn, north London, during a show staged for Jeff Stein’s cameras, a flabby Moon underperformed, and Townshend lashed out at his perceived punk enemies in the crowd. “Well, this wasn’t fucking worth filming, Stein,” the guitarist huffily declared into his microphone. “Might as well send the cameramen home.”

Townshend’s anger didn’t abate over the Christmas period and, at home with his parents in Ealing, an argument provoked him to punch his hand through a window, causing lacerations that were to delay the album’s progress by two months. Then, just as the sessions were set to recommence, the band’s new keyboard player John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick broke his arm after falling out of a cab following a drinking session with Moon (requiring the emergency drafting of erstwhile Zombie, Rod Argent).

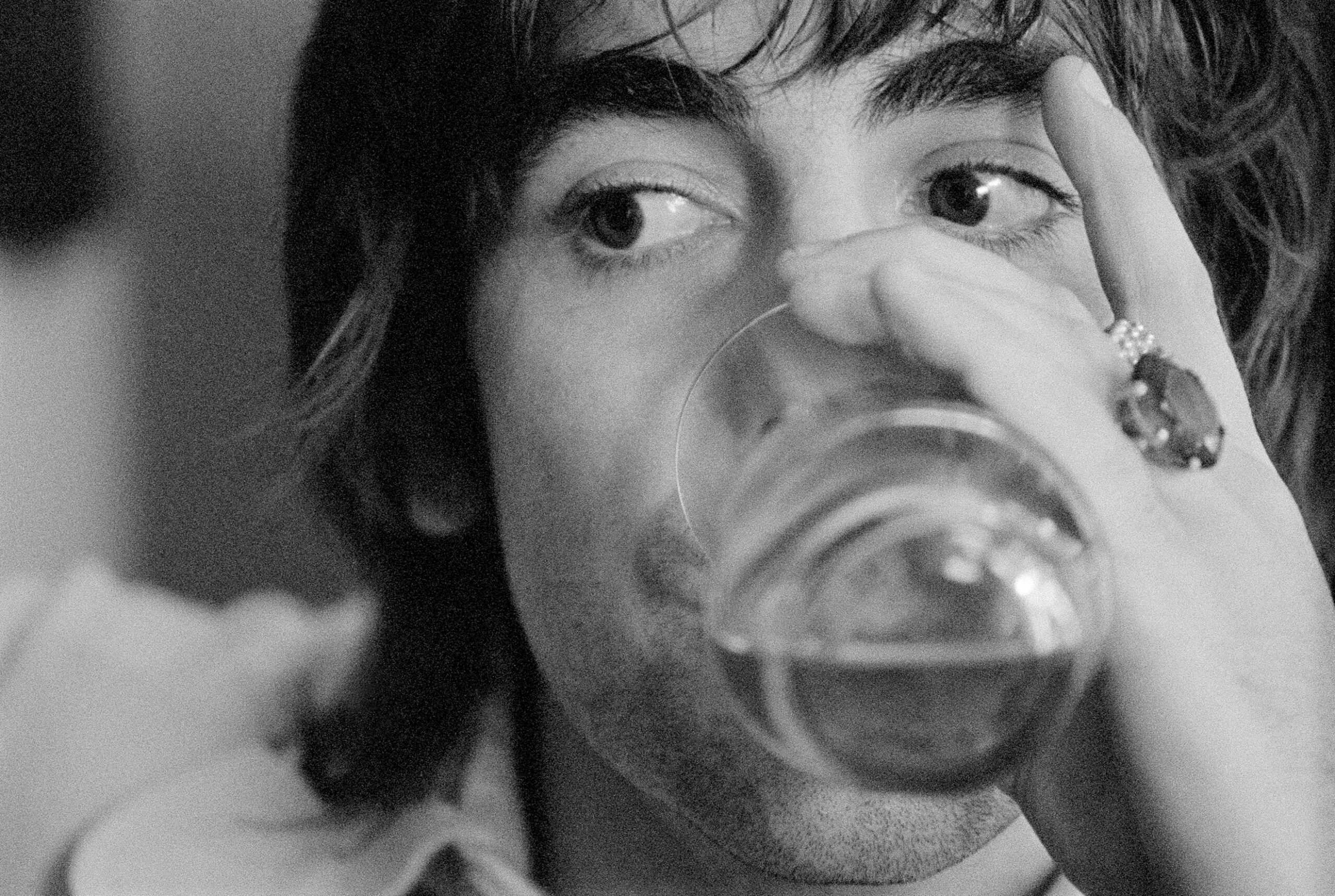

Ever the optimist: Moon keeps his glass half full, 1972.

In March ’78, at RAK Studios in St John’s Wood, Moon struggled to get to grips with the 6/8 time signature of Townshend’s Music Must Change. The difficulty, from Entwistle’s perspective, was that the drummer “couldn’t think of anything to play”. Daltrey later said of the song, “Keith couldn’t play to it. Keith could play great Moon drums, and that was it.”

For Townshend, the problem was more acute. “He did actually physically stop playing,” the guitarist told me in 2019. “We were recording the song, and he couldn’t play, and we ended up using footsteps as the rhythm.”

Townshend held an emergency summit at a nearby restaurant, reportedly threatening to sack Moon if he didn’t sort himself out. Moon insisted, “I can do triplet jazz!” then comically announced, “I am the best… Keith Moon-type drummer in the world!”

Still, Moon heeded Townshend’s warning, and most of the drummer’s parts for Who Are You were far more capably overdubbed in April ’78, back at Ramport, in the final two weeks of recording. Somehow he managed to find a middle ground (particularly on the stomping, synth-led Had Enough and Sister Disco) between straight-ahead, four-on-the-floor rock beats and his baroque drum fills. His old fire had suddenly returned.

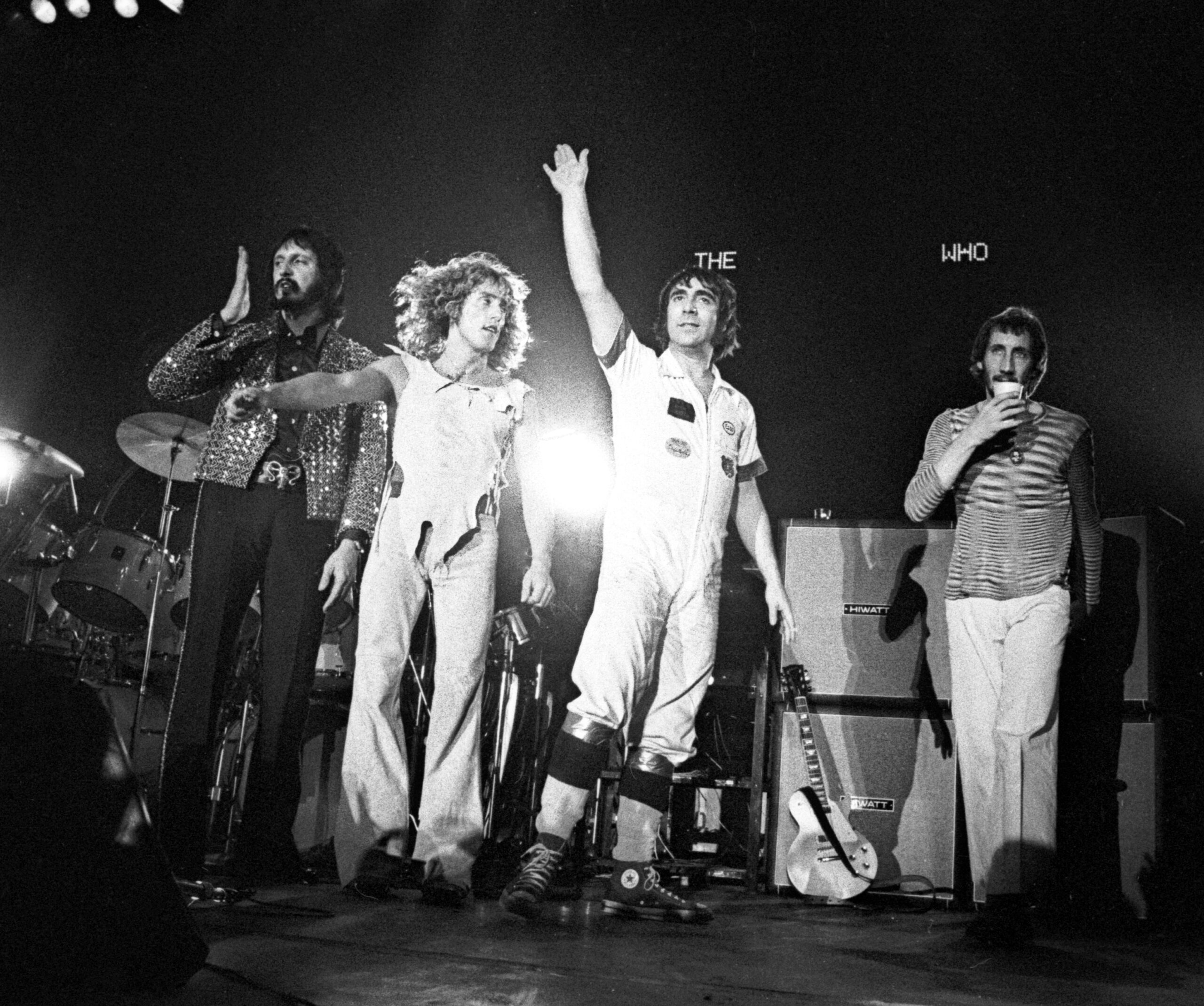

Who are they?: The Who, circa 1965. [From left: Daltrey, Entwistle, Townshend, Moon.]

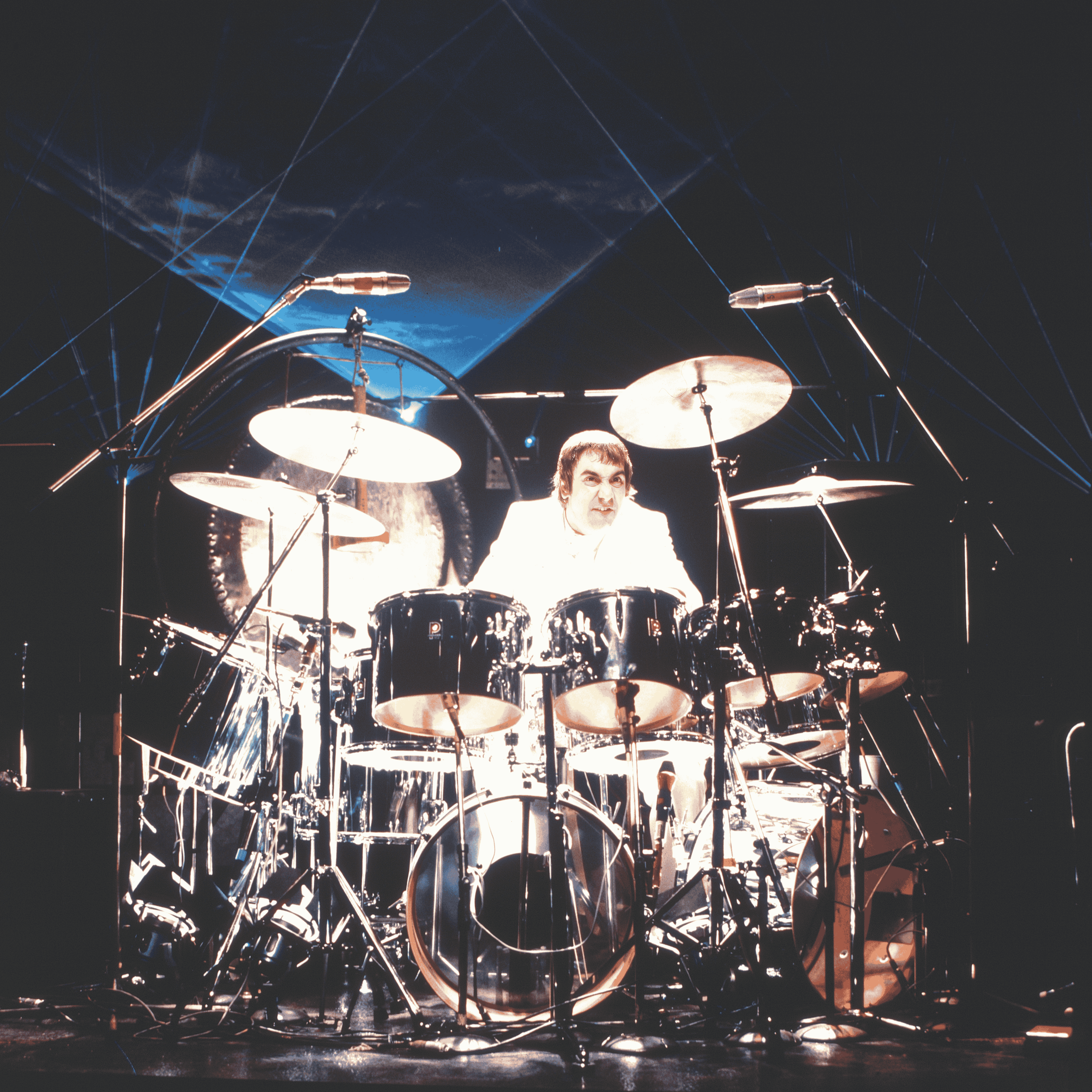

“IT WAS JUST FUCKING PHENOMENAL,” enthused John Entwistle of the explosive drum solo that Keith Moon played, for the benefit of only the other members of The Who and their crew, at the end of a particularly productive day of filming and recording at Ramport, on May 4, 1978. The plan had been for Jeff Stein to film the band miming to the title track and first single from Who Are You. Spontaneously the group began jamming on top of the master tape, in spur-of-the-moment performances quickly captured by Jon Astley and subsequently cut into the video.

In the footage, Moon typically looned around, his headphones gaffer-taped to his head, but also played brilliantly. Three weeks later, on May 25, The Who returned to the stage, at Shepperton, performing for an invited audience what would be the classic line-up’s last show together. Jeff Stein was lacking decent film takes of Baba O’Riley and Won’t Get Fooled Again and the gig was set up expressly for this purpose. But in the end – as revealed in the new box set’s previously unreleased Who Are You outtakes – the band played for far longer, hitting peaks and sliding into troughs.

Moon pummelled through opener Baba O’Riley, then began flailing more wildly, erratically pushing and pulling the tempo of Entwistle’s My Wife, losing the plot several times as the band threatened to fall apart. Periodically, he broke out into – as if to prove a point – nifty triplet jazz rolls, before a messy Who Are You prompted Daltrey to apologise to the crowd, promising that the upcoming recorded version of the song sounded “absolutely nothing like that at all”.

Feeling boar-ed?: Keith Moon has a friend for dinner, 1972.

Later, Moon experienced a surge of energy (the result, reportedly, of a hefty double shovel of cocaine) and turned in a charged performance of Won’t Get Fooled Again that was both solid and flashy. At its close, Moon, for one more time, climbed over his drum kit, and was immediately hugged by Townshend.

Speaking to the Evening Standard three months later, the drummer was doubtful about The Who’s ongoing prospects as a touring band. “As regards records and films, I can see a future for The Who,” he said. “Not on the road, not in the same way as the Stones. I certainly see The Who broadening their horizons.” He went on to talk up a new holographic film technology that was apparently in development by the band’s team. “I’m much more involved, much more interested in some of the things that we’re doing at Shepperton,” he emphasised.

In August, the same month that Who Are You was released (peaking at UK Number 6 and US Number 2), a private screening of a rough cut of The Kids Are Alright was held for the band and their associates. Spanning the period between their performance of I Can’t Explain for the US Shindig! TV show in 1965 and the May ’78 gig at Shepperton, it documented just how much Moon had changed in just 13 years.

“It must have been horrific for Keith,” Daltrey later empathised. “This young drummer, great-looking kid, going bananas, who turns out at the end of the film a fat old thing… falling off the drums, being held up. He’d gone to seed, and he wanted to get it back.”

Send-off: Moon bids adieu, Rotterdam, October 27, 1975.

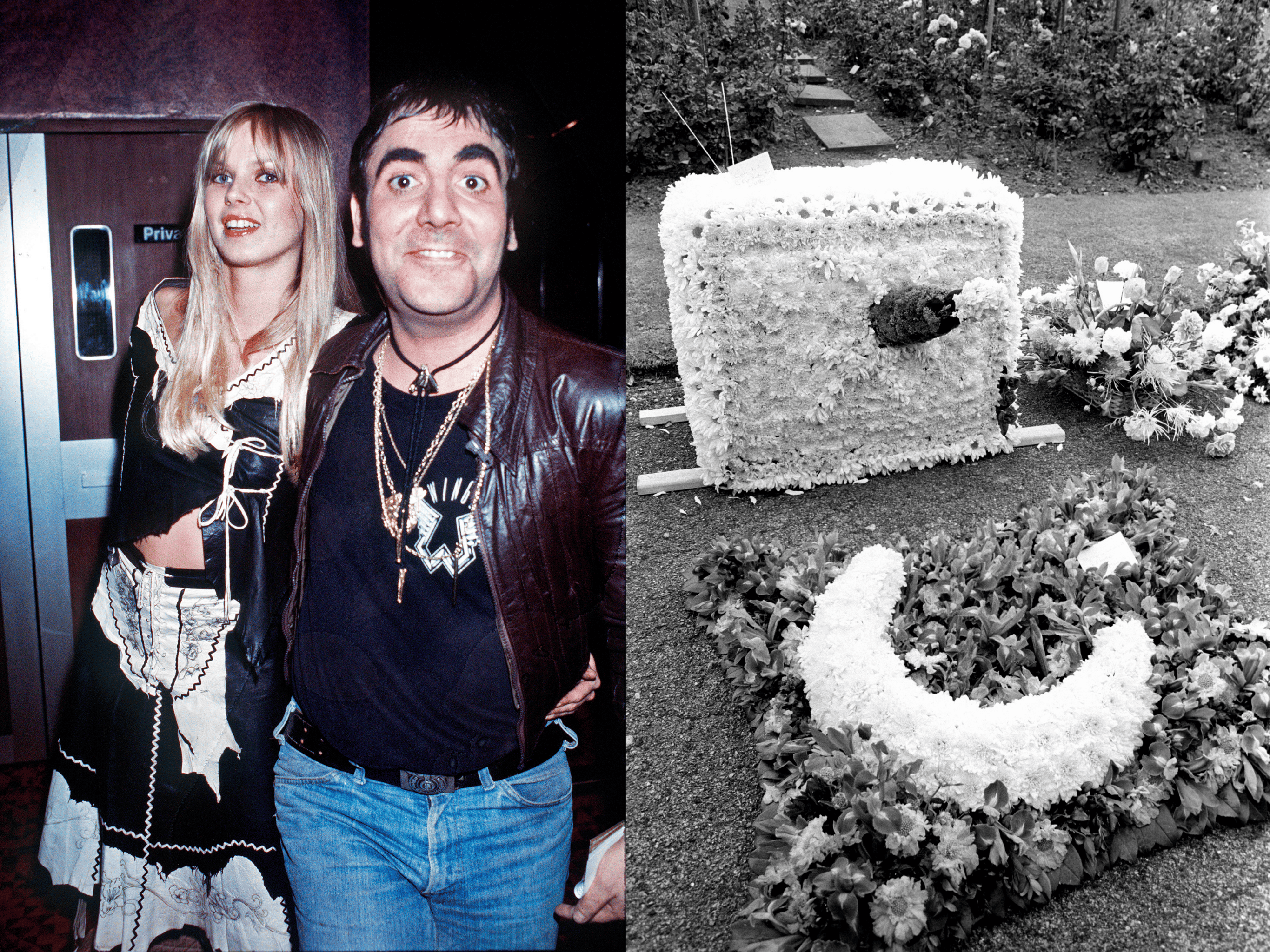

THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE OF KEITH MOON was on Wednesday, September 6, 1978, at a Paul McCartney-organised screening of The Buddy Holly Story at the Leicester Square Odeon, preceded by a bash at the Peppermint Park restaurant in Covent Garden. Showing support for his other ex-Beatle pal, The Who’s drummer turned up wearing a Wings T-shirt.

Kenney Jones, the ex-Faces drummer (who was, under terrible circumstances, soon to replace Moon in the ranks of The Who), ended up hanging out with his fellow sticksman that evening. “I found myself at a table with Keith, his girlfriend, Paul and Linda, and David Frost,” Jones recalled to MOJO in 2024. “Keith and I were talking. I said, How you been? He said, ‘Yeah, great. I’m not taking any drugs and I’ve stopped drinking completely.’ It was more the drinking with Moony than anything.

“He said, ‘I’m taking these pills. And they keep me off drink. If I take one, I get violently ill.’” The rest is all grim detail. Moon and Walter-Lax left the screening midway, returning to the top-floor flat in Curzon Place, Mayfair, that the couple were renting from singer Harry Nilsson. Nilsson had been reluctant to lease the apartment to Moon, believing it to be cursed, following the death there of Cass Elliot of The Mamas & The Papas in the summer of 1974. Townshend had reassured Nilsson, saying, “lightning wouldn’t strike in the same place twice”.

Back at home, Moon took more of the Heminevrin sedatives prescribed to alleviate his alcohol withdrawal symptoms (his doctor, restricting him to three tablets a day, had naively given the drummer a bottle filled with 100). He fell asleep in front of the TV while watching the Vincent Price-starring 1971 horror flick, The Abominable Dr. Phibes. In the morning, he woke and ate a breakfast of steak and eggs made for him by Walter-Lax, popped more pills and then nodded out. On the afternoon of September 7, his girlfriend woke to find him dead. A post-mortem found 32 pills in his system.

“I said to Pete, we don’t have to stop. You can’t replace Keith, but you can keep the music going.”

“I turn the TV on,” Kenney Jones remembered, “and the news came on. Y’know, ‘Keith Moon was found dead in his flat.’ I said, What the fuck? I just left him. He’s up to mischief again. I never believed it. Then I found out it was real.”

In a state of shock, their minds fogged by grief, Daltrey and Townshend could never quite remember who called who with the awful news: the singer claimed it was the guitarist, who swore it was the other way around. After holding a three-quarters band meeting with manager Bill Curbishley, The Who resolved to continue.

“I said to Pete, We don’t have to stop,” Daltrey remembered. “You can’t replace Keith, but you can keep the music going. It’s all about the music in the end.”

Townshend subsequently released a media statement. “No one could ever take Keith’s place,” he stressed. “But we’re more determined than ever to carry on.”

Moon’s funeral was a private ceremony, with the details kept secret from the press, on September 13 at Golders Green Crematorium in north London. When it came to the many floral tributes, Daltrey had one commissioned in the shape of a lobbed champagne bottle poking out of a TV screen. Kenney Jones was there, but sneaked in and out unnoticed.

“I didn’t want to see anyone,” he explained. “So I crept up, I did a little poem, little bunch of flowers, and I just left it and nipped out, so no one knew I was there.”

One week apart: Moon with Annette Walter-Lax, September 6, 1978; One week later, floral tributes at Moon’s funeral.

IN A DARKLY RESONANT JOKE – ONE THAT HE SURELY would have appreciated – Keith Moon had been photographed with the group on the cover of Who Are You amid cable clutter and in front of their gargantuan PA system, straddling a chair with the words “Not To Be Taken Away” stencilled on its back. As Townshend had acknowledged in his missive, the Moon-shaped hole in The Who was to prove impossible to fill.

“Pete turned to drink,” Daltrey told MOJO in 2018. “Pete never did drugs, all the way through, ’til Keith died. I think that was from heartbreak. We all were traumatised by that. That was hard to get over. Keith was only 32. It’s young, innit.

“The worst thing was we were expecting it any time with him. ’Cos he had nine lives, and he lived nine lives as well (laughs). The shock became even greater for some reason.”

In November 1978, Kenney Jones – who had previously played on seven tracks on 1975’s Tommy film soundtrack (while Moon was filming Stardust) – was revealed as the new drummer in The Who.

The next generation: Kenney Jones, 1979.

“When I said I would join,” Jones recalled, “I said, I’m not going to copy Keith Moon. I can only play me. That’s all I can do. I’m a completely different drummer. I’m straighter. But I like certain things Keith did, so I want to do them. I’m going to complement them if I can, but I’ll have to do it my way.”

This new version of The Who debuted at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, north London, on May 2, 1979. Their return coincided with a Mod revival at least part-ignited by The Jam, as evidenced by the packs of youths arriving at the venue on scooters and wearing parkas. It was a resurgence further fuelled in the summer of 1979 by the cinematic release of the film version of Quadrophenia.

But, for Roger Daltrey in particular, something was irretrievably lost from The Who with the death of Moon. “Without Keith, we weren’t the band we were,” he said. “But then I was in a strange place myself. So it was hard.” In many ways, the singer has remained the keeper of the drummer’s flame, pushing for decades to have a Moon biopic (provisionally titled The Real Me and still in development) brought to the screen.

“The thunder of Moon’s drums,” Daltrey told me, still awed by his long-gone pal’s unique playing, “that will reverberate for ever.”

Moon himself, too, it seems, always kept one eye on his legend. Writer/publicist Keith Altham later remembered visiting the drummer on an unspecified date in a London hospital “after a suspected stroke”. Altham voiced aloud his hope that Moon would take this particular health scare as a warning to slow down.

“You know me, dear boy,” the drummer announced. “Mortality, I never consider. Now immortality I take quite seriously.”

Final flight: Moon during The Who’s last show, Shepperton Studios, May 25, 1978.