Mojo

Presents

Heaven And Hell

The Woodstock Festival has always been touted as the crystallising moment of the rock counterculture – an Eden with mud and acid and granola that gave its name to an era and a generation. But was it the event we think we remember? Was the music as good as history tells? And how did John Sebastian survive multiple electrocutions?

Words: Michael Simmons

As soon as I saw the line-up, I knew I was going,” remembers Fred Weis. “It was clear this was going to be phenomenal.”

In 1969, Weis was a 16-year old high school student and devoted rock music fan with shoulder-length hair. These characteristics would earn him the then current handle of “hippy”. The resident of suburban Philadelphia had already seen Jimi Hendrix and Cream live, but “the breadth” of the line-up for the Woodstock Music & Art Fair was like a candy store for a kid with a deep sugar jones. It was billed as “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days Of Peace & Music” on August 15-17 in the town of Bethel (listed as the community of White Lake on the poster), two hours north of Manhattan in upstate New York. The 30 acts included big-name rockers Hendrix, The Who, Country Joe And The Fish, Jefferson Airplane, The Band, Janis Joplin, Sly And The Family Stone, Grateful Dead, Ten Years After, Canned Heat, Johnny Winter and Creedence Clearwater Revival, veteran folkies Joan Baez, Richie Havens, Tim Hardin and newer minstrels Arlo Guthrie and Melanie. Also listed were names few had heard of: Santana, Joe Cocker and Mountain (this would be the latter’s third gig). Even more green was a supergroup made up of former members of The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and The Hollies – Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. This would be their second public appearance.

“I sent away $18 and bought tickets,” recounts Weis. With parental approval secured, it was to be his first festival. “There was the Atlantic City Pop Festival a couple weeks earlier – I had friends who went to that. But as far as I knew, I was the only friend in my peer group that was going to Woodstock.”

He travelled light. “I had a little Boy Scout rucksack and I went by bus from Philadelphia to New York City. As soon as I got to the bus terminal in New York, I could see something was happening ’cos there were thousands of kids there.” But that was a mere taste of things to come. Another bus proceeded north. “When we got up to the two-lane roads upstate, cars were pulled up on the grassy sides and people were setting up camps – and we were still 20, 30 miles away. Our driver pulled into the lane of the opposing traffic, beeped his horn and barrelled through.”

The traffic became so thick that the bus could no longer move forward and the young passengers disembarked. “I started walking. I was completely astounded ’cos there were people setting up tents, playing guitars and I thought, Don’t you wanna see the festival?” Eventually he reached the site. “It was clear that things were not together. There were no ticket takers. There was a four-foot high plastic fence that was horizontal by that time. People were just walking over it. We went over a rise and then you could see a bowl and people extending out into the distance. I took a spot close to the stage – close enough that I could see everything. People were still working on the stage.”

Although Weis had experience with drugs, he was going through an abstinence phase. “I turned down passed joints, but there was a contact high, though not from second-hand smoke – it’s just that everyone was… happy. There was a shared consciousness. It was immediately clear this wasn’t just a concert – it was a community.”

And the music hadn’t even started yet.

“Every now and then, even though your eyes were open, you’d see black – one of the symptoms of being electrocuted.”

John Sebastian

Fred Weis’s memories chime with the classic version of the Woodstock story, passed down from generation to generation: the encapsulation of the ’60s promise; a gathering of seekers looking, in the words of Joni Mitchell’s song, written in the festival’s immediate wake, to get themselves “back to the garden”. But there was more than one Woodstock 1969. Competing narratives are provided by attendees, musicians, subsequent soundtrack albums and Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 documentary film. The latter won the 1971 Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, and fundamentally shaped perceptions of the event. “Far more people saw the Woodstock movie than were at the festival,” notes Woodstock attendee and music business veteran Danny Goldberg. “The movie was a much more influential thing. It’s still the most successful concert film by a lot.”

Ex-Lovin’ Spoonful singer-songwriter John Sebastian was there – in tie-dyed denim, he’s one of the stars of Wadleigh’s film – and his experience embodies many of Woodstock’s contradictions: literal and metaphorical highs balanced by chaotic planning and technical gaffes that could easily have turned tragic. Sebastian wasn’t even scheduled to play. He’d been touring the East Coast solo when producer Paul Rothchild suggested he visit the festival as a spectator. On August 15 he went to the Albany, New York airport to see if he could hitch a ride to Bethel. It was there he spotted ex-Spoonful roadie Walter Gundy, by then working for The Incredible String Band, loading a helicopter.

“I start gesticulating,” Sebastian recalls today. “Lo and behold, he turns around, sees me and gestures for me to join him. I walked onto the tarmac and he goes, ‘You’re trying to get to the festival.’ I say that’s right. He says, ‘I’m your only chance. Everything’s jammed for miles and miles. Get in the helicopter.’ I have no guitar, no suitcase – I don’t have anything. (laughs) But I get in the helicopter because I’ve done this before with Walter Gundy – I trust him.”

Guaranteed backstage privileges due to his VIP status, Sebastian found himself talking to lighting designer/technical director/MC Chip Monck and noticed a tent near the stage where musicians were storing expensive instruments. “I say to Chip, ‘You know that tent in front of the stage is gonna get totally soaked with mud, so you oughta put a cardboard box outside with a sign that says SHOES HERE – that’ll solve that.’ Chip turns around and says, ‘OK – you’re in charge of the tent.’” Becoming a Woodstock tent custodian brought extra benefits: “It also gave me a chance to get out of the rain for three days. I never left the site for a cute little hotel room.”

The next day was Saturday. That, remembers Sebastian, was when the rainstorms began. “I’m on-stage with [promoters] Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld,” recalls Sebastian. “They’re saying ‘We gotta do something – there’s water all over the stage – we can’t bring the amplifiers on – we’ve gotta have somebody sweepin’ off the stage.’”

Lang and Kornfeld had another bright idea. “They say, ‘What we need now is one guy that can hold them with one acoustic guitar that doesn’t need electricity,’” says Sebastian. “And I’m nodding my head: Yeah that sure is what we need all right! And it’s like a Laurel And Hardy take. I realise, Oh! You guys are lookin’ at me! (laughs) I say, Guys, I may have a thumb pick in my pocket, but I don’t have a guitar – or anything! And Michael says, ‘You have five minutes to find one.’”

Sebastian borrowed Tim Hardin’s and stepped in front of the crowd. But an acoustic guitar didn’t fully insulate against the interaction of water and electricity – he was still singing into a live microphone. “Every now and then, even though your eyes were open, you’d see black – one of the symptoms of being electrocuted.”

It must be said, not all of Woodstock’s participants remember rain on the Saturday. But whenever it came, it was inadequately planned-for and caused multiple problems. “Our equipment got rained on – we lost some part of our equipment,” recounts lead guitarist Barry Melton of Country Joe And The Fish. “But,” he adds with a shrug, “we had a good time.” Melton is seen in the Woodstock documentary spontaneously leading the crowd in chanting “NO RAIN! NO RAIN!” Ten Years After followed Country Joe, and drummer Ric Lee noticed that the lack of weather preparations were perilous. “The towers that supported the PA were totally inadequate. There was no [solid] stage cover, just a piece of tarpaulin that had been hastily strung up and was flapping in the breeze.” They faced the same danger Sebastian experienced – and they were a fully electric band. “The stage was soaking wet and became live. But to his credit, Michael Lang refused to let anyone go on-stage until it was made safe.”

At least the musicians had shelter – the Holiday Inn motel in nearby Liberty. The crowd had no such refuge. Rock critic Ellen Sander covered the festival for the Saturday Review. “There was no shelter from the rain and the audience just got wet. But they worked with that. And they were complimented on it by the MCs.” Back at the motel, the players were having a party. Barry Melton recalls a hallway jam session with him and Jerry Garcia of the Dead and hotshot picker David Bromberg. “And Janis fell by – it was like an off-stage section of the concert. It was pretty cool.”

Sander recalls another scene at the motel bar where Garcia, Joplin, Country Joe McDonald, Richie Havens, Tim Hardin and members of Jefferson Airplane all linked arms, “swaying from side to side and laughing” while singing along with Hey Jude after someone fed enough coins into the jukebox for it to play “60 times end to end.”

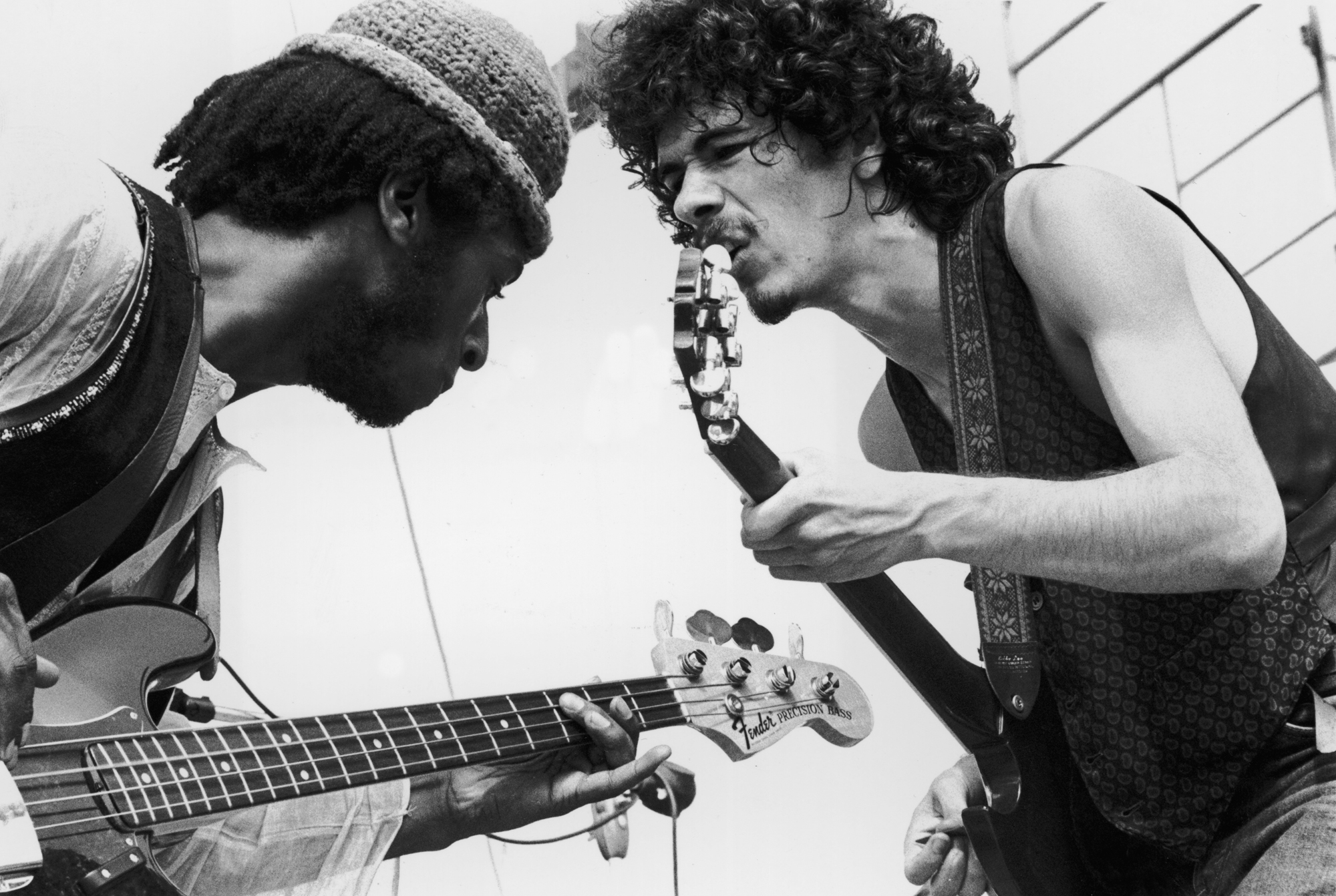

Carlos Santana and David Brown perform with the group Santana

There’s no doubt that good luck conspired with the tenor of the times to prevent Woodstock from being a catastrophe. In that respect, Fred Weis was a perfect Woodstock citizen. In addition to digging the music (he cites Hendrix, the Airplane, The Who and CSN&Y as highlights), he got into the communal spirit. “There were makeshift buildings where the bad trip tent was, that’s where the Hog Farm [commune] was cooking food and ladling out big dishes of goulash food to everyone in line. Everyone was very courteous, I asked ‘Do you need a hand?’ They said, ‘Yeah,’ gave me a ladle and then I was dishing out the food.”

Along with the Grateful Dead, San Francisco’s Jefferson Airplane personified what we think of as Woodstock’s spirit. The band lived communally and their lyrics advocated radical politics and celebrated tribal hippy culture. “The Gestalt consciousness of people that were at the festival – the we’re-all-in-this-together mentality – you don’t get that at festivals most of the time,” noted Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen. “You get people pushing you out of the way so they can see better. A lot of it had to do with the times. At that moment, the so-called counterculture – the them-us dichotomy – became apparent. That sense of cultural identity separated Woodstock.”

There were other factors. The connection between the name “Woodstock” and Bob Dylan can’t be overestimated. The festival was originally planned for Dylan’s then-hometown and the magnetic pull of his name – even though he wasn’t there – was powerful. Kaukonen also mentions the mystical X-factor of the area. The Catskill Mountains had been home to Native American tribes and longtime residents tell of encounters with the spirits of dead Indians, among other supernatural tales. “There’s a feeling in those woods – could it be Rip Van Winkle or ley lines?” Kaukonen says. “Who knows? Maybe that had something to do with Woodstock.” He’s not the only musician of the era who would later choose to live in the area.

Others at the festival have described moments of strange synchronicity. Weis experienced his own. “Around early evening Saturday, I was in a perfectly good position, but I suddenly had the urge to change where I was. I’m a quiet guy – I’m not aggressive – and I just suddenly got aggressive and started forcing my way through the crowd in this random pattern. It wasn’t a beeline – I just wanted to go somewhere. I did this for 10 minutes and suddenly I stopped and realised I was looking at the back of my best friend’s head. I didn’t even know he was there!”

Danny Goldberg was a 19-year-old clerk at music biz trade mag Billboard. When no one else wanted to cover the festival, he volunteered. “Walking around seeing all these faces, hippies, these stoned people, the sweetness and sense of community. We showed we could get together and not kill each other. It was part of the continuum of the period.”

Activist and Yippie co-founder Abbie Hoffman had been doing yeoman’s work, comforting kids in the bad trips tent who’d flipped out on psychedelics, alongside the Hog Farm commune, including Woodstock MC Hugh Romney (later known as Wavy Gravy). But when he hopped on-stage during The Who’s set to chastise the crowd for having fun while MC5 manager/political organiser John Sinclair was doing serious prison time for a pedestrian pot rap, Pete Townshend whacked him with his guitar and sent Hoffman flying into the crowd.

“From the age of 18 months I was brought up side of stage in my father’s swing band,” says Townshend now. “The idea of walking out and interrupting a show is not in my genes. It’s a sacred space.” And yet in hindsight, he thinks Hoffman had a point. “He was excited and wanted to call the entire chaotic love fest to order. In that respect we were the same. It all felt hypocritical.”

Woodstock ended at 11.10am Monday morning, August 18, with Jimi Hendrix. Andy Zax – producer of Rhino’s new Woodstock box set – didn’t attend, but he has pored over the minutiae of the event. “By the time Hendrix got on-stage,” says Zax, “there was a small cadre of diehards. Most of the audience had gone home, people had to go to school or work. They were wet, covered in mud, starving, miserable. If you look at photos of Hendrix playing, you can see it’s thinned out. Its presence in the movie gave it a totemic significance that it may not have had at the moment.”

Fred Weis returned home by thumb. “I was standing on the back bumper of a VW Bug, the tips of our fingers holding onto the rain gutter for about 30 miles – not going very fast ’cos of all the other cars. Then I hitchhiked back to Philly.” Jorma Kaukonen drove the Airplane’s station wagon to New York City: “We had to go do [chat show] The Dick Cavett Show [their performance is on YouTube]. The roads were blocked by parked cars on either side, so we had to squeeze our way through. At this point I say, Anybody who had their car parked on the back road to Woodstock who lost trim that day – I apologise.”

“The film is a spectacular piece of film-making, but it isn’t completely congruent with reality.”

Andy Zax

There were initially two Woodstock soundtrack albums: one in 1970 and its 1971 sequel. Andy Zax produced the revamped 2009 box set, as well as this year’s 3-CD, 5-LP, 10-CD and 38-CD offerings. (The latter contains each act’s entire set. Listeners can finally decide for themselves how good the event’s music really was.) What many people don’t know is how many post-production tricks went into the film and records. “The original triple album is stuff that was in the movie – theoretically,” says Zax. “The film is a spectacular piece of film-making, but it isn’t completely congruent with reality.”

In the movie, the original studio recording of Going Up The Country by Canned Heat is used, while the soundtrack is live from Woodstock, albeit abbreviated. At the festival, Arlo Guthrie’s vocal mike dropped out for the first 90 seconds of Coming Into Los Angeles – the version heard was recorded at the Troubadour in LA in December 1969. The audience recording level was too low during Country Joe’s infamous Fish/Fuck Cheer. So it was augmented in the studio during post-production. CSNY’s Marrakesh Express on the original Woodstock Two soundtrack has overdubs and their Sea Of Madness and Wooden Ships were recorded at the Fillmore East in September 1969. The original Mountain tracks on …Two are post-event as well.

Zax and engineer Brian Kehew restored all the original recordings for the 50th anniversary sets. “We’ve tried to make it as naturalistic as we can. We’ve ruthlessly expunged anything fake. None of our mixes have overdubs, sweetening, edits. There are one or two exceptions where we made things more listenable.” Because of the heat, moisture and equipment issues, the Blood, Sweat & Tears horns were out of tune, a problem that’s been fixed via a relatively new technology called polyphonic tuning. The multitrack of sitar master Ravi Shankar’s set had vanished – only a mono tape was available. An engineer at Abbey Road studios in London was able to isolate and extract the tracks through another new technique called de-mixing, from which a stereo mix was created. It’s another version of Woodstock to add to all the others.

Hog Farm commune members

The 50 years that followed Woodstock were not the utopia its boosters hoped for. Woodstock’s “good vibes” didn’t even last a year: that December was Altamont – a Rolling Stones mini-fest that ended in violence and murder. “If you look at the Isle Of Wight Festival the next year, 1970, it was nothing like Woodstock,” says Ric Lee. “The money men had moved in. They saw they could make lots of money by having lots of people at big festivals. When the kids at the Isle Of Wight tried to turn it into a free festival, they turned the dogs on them and beat them with sticks.” Danny Goldberg: “There was this brief period where things changed fast and there was this illusion everything could change fast. That was not realistic.”

Original Woodstock promoter Michael Lang co-produced follow-up festivals in 1994 and 1999. The latter was the opposite of its peaceful predecessor 30 years earlier. Water and food was confiscated from attendees in an effort to force them to purchase overpriced staples onsite. Four gang rapes were reported and random violence was so harrowing that video channel MTV evacuated its crew after providing live coverage. For Woodstock’s 50th anniversary, Lang planned yet another gathering with generational bookends Dead & Company and Jay Z billed, but it’s been plagued by site difficulties and the withdrawal of a key financier. As MOJO went to press, a new site had been chosen and Lang insisted that Woodstock 50 would happen.

Yet despite the ticking clock of climate change and other looming disasters, the human race has made progress. Country Joe and other interviewees point to the popularity of yoga and health food (granola was, in the immortal words of Wavy Gravy, the “breakfast in bed for 400,000”), the acceptance of and respect for racial and gender differences, and the decriminalisation of cannabis in several US states as examples of Woodstock Nation values and lifestyle. Even psychedelics have made a recent comeback, with the popularisation of micro-dosing and Oakland CA’s decriminalisation of magic mushrooms and peyote. (“‘Don’t eat the brown acid’ implied that there was good acid,” quips Danny Goldberg.)

“The world is blending,” says Country Joe in response to cynics who view Abbie Hoffman’s ‘Woodstock Nation’ as a myth of boomer nostalgia. “I realise young people today hear ‘hippy, hippy, hippy’ and they’re sick of hearing about it. Well, in a way I’m sick of hearing it too (laughs), but it was an honour to be part of that generation.”

Critics have noted that Woodstock also inspired corporate exploitation of the vast youth demographic. Plus ça change, says McDonald: “The music business has always been what it is. It makes money from music.” His bandmate Barry Melton insists on a positive effect the event and the culture that spawned it had on a society that refused to examine its flaws. “Woodstock was not mainstream America – which looked very different back then. Quite a different picture of what society was about was created at Woodstock and seemed to have stuck to some degree. It was a generation coming of age that was quite different than the ones that preceded it.”

Meanwhile, Rhino’s box spotlights what kids like Fred Weis and Danny Goldberg went to Woodstock for in the first place. “It was mostly a music festival,” says the latter. “People were there for the music. Music has its own value – it’s not just a means to an end to make people change their politics. It’s about honouring the music itself as one of the things that makes life worth living.”

This article first appeared in issue 310 of Mojo

Images: Getty