Mojo

FEATURE

Shaman’s Blues

By the dawn of 1969, The Doors were one of the hottest bands on the planet – making headlines, packing shows – yet the pressures of work and fame were already impacting on their music. Then, on-stage in Miami, Jim Morrison took something out of his trousers and changed his band’s trajectory irrevocably. But did Miami unhinge The Doors, or was it “the essence of what rock’n’roll’s about”? Both? Or neither? Dave DiMartino knows, because he was there.

The Doors: Drummer John Densmore, singer Jim Morrison and keyboardist Ray Manzarek, playing at the Fillmore East.

IT WAS A HOT AND STEAMY SUNDAY NIGHT IN MIAMI on March 1, 1969 – and it was even hotter and steamier inside Dinner Key Auditorium, a former aircraft hangar off Biscayne Bay in Coconut Grove. Twelve thousand concert fans sat crammed into the auditorium’s confines, sweating, drinking, smoking, and watching, eyes wide open, as the man on-stage politely shared his thoughts.

Some members of the audience applauded. Some cheered. Some whooped in appreciation. And some had climbed the outside walls, come in through the windows, and were hanging from the rafters, watching. It was nuts; I was there.

“Lettin’ people tell you what you’re gonna do!” the man scolded. “Lettin’ people push you around!”

A pause. “How long do you think it’s gonna last? How long are you gonna let it go on? How long are you gonna let ’em push you around? How long?”

There was discomfort among some in the audience. They’d paid $6 and expected to watch this man sing, not… whatever this was.

Then, a different tack. “Maybe you like it,” he taunted. “Maybe you like being pushed around!”

Yeah, that’s it.

“Maybe you love it! Maybe you love getting your face stuck in the shit! Come on! You love it, don’t ya? You love it!”

The punchline. The night’s epiphany. The final provocation. The entire point:

“You’re all a bunch of slaves! Bunch of slaves! You’re all a bunch of slaves! Letting everybody push you around.

“What are you gonna do about it?

“What are you gonna do about it?

“What are you gonna do about it?

“What are you gonna do about it?

“What are you gonna do about it?

“What are you gonna do?

A fair question.

And what did the audience do about it?

Very literally, they threw that man off the stage.

Welcome to Miami, Jim Morrison.

“Maybe you love getting’ your face stuck in the shit! Come on! You love it, don’t ya? You love it!”

Jim Morrison

IN LESS THAN A WEEK, SEVERAL warrants were issued for Jim Morrison’s arrest, for charges ranging from “lewd and lascivious behaviour in public by exposing his private parts and by simulating masturbation and oral copulation,” to simple public profanity and public drunkenness. In short, Morrison was said to have pulled out his penis for the world to see on that Miami stage. Did he actually do it? The band has always denied he did and no pictures of the alleged exposure have ever surfaced. But Morrison himself said, “Uh-oh – I think I exposed myself,” when leaving the stage that night, according to a 1969 Rolling Stone account of the concert. And speaking as an eye-witness who was actually there, aged 15, yes, I saw him do it, and so did the people I was with.

The night would hang over Jim Morrison for the remainder of his life, and significantly alter his band’s career path. Some say that March 1, 1969 was the night it all fell apart for The Doors. Some say things actually got better. Either way, it epitomised a crazy phase where soaring commercial success coincided with the oddest, most uneven music they would ever record.

It hadn’t always been this way. In the early days – after Morrison, organist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore met in Los Angeles, took a bandname inspired by Aldous Huxley and William Blake, and signed to Elektra Records – being as commercial as new labelmates Love might have been more than enough. But when second single Light My Fire topped the Billboard charts in 1967, The Doors’ trajectory was set. There were TV appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show, on the Jonathan Winters Show. There were catchy follow-up singles, People Are Strange and Love Me Two Times, counterbalancing the deliciously exploratory epics, The End and When The Music’s Over. There was no other band like The Doors, and this was their time.

“Sixty-seven was the coolest period,” Robby Krieger says today. “Everything was amazing. Light My Fire was Number 1, it looked like we were going to get out of Vietnam, and it seemed like we had the power, you know? But then in ’68, everything kind of changed. It was like the devil took over or something. Not only politically… Jim for some reason got back into drinking liquor, which was never good for him. Before, it was LSD or pot, and he was always great in those days, but the minute he would drink too much, it would just… everything would go to shit.”

1968 began with the band entering Hollywood’s ID Sound with engineer Bruce Botnick to rehearse new material and record previews for Paul Rothchild, who’d produced the band’s first two albums. But they were short of songs and Morrison was focused on his planned epic, Celebration Of The Lizard – a lengthy, theatrical mixture of spoken word and music that would carry on the tradition of The End and When The Music’s Over but fill a complete album side. It wasn’t easy going.

“We were into it,” insists Krieger. “We were trying to make it work. It was just one of those things that you really need a couple of years in a club in order to really get it down. And something like that, especially, where it’s 30 minutes long – it would’ve been nice to be able to do that. And we did play it live, quite a few times in different versions, but by the time we tried it in the studio, part of it was cool, but then other parts weren’t working.”

Botnick played the ID Sound version of Celebration… to Rothchild. The producer’s verdict?

“Paul just felt that it was not ready for prime time,” says Botnick now. “And also he was concerned about putting in another long, theatrical piece that made three in a row, with The End and When The Music’s Over.”

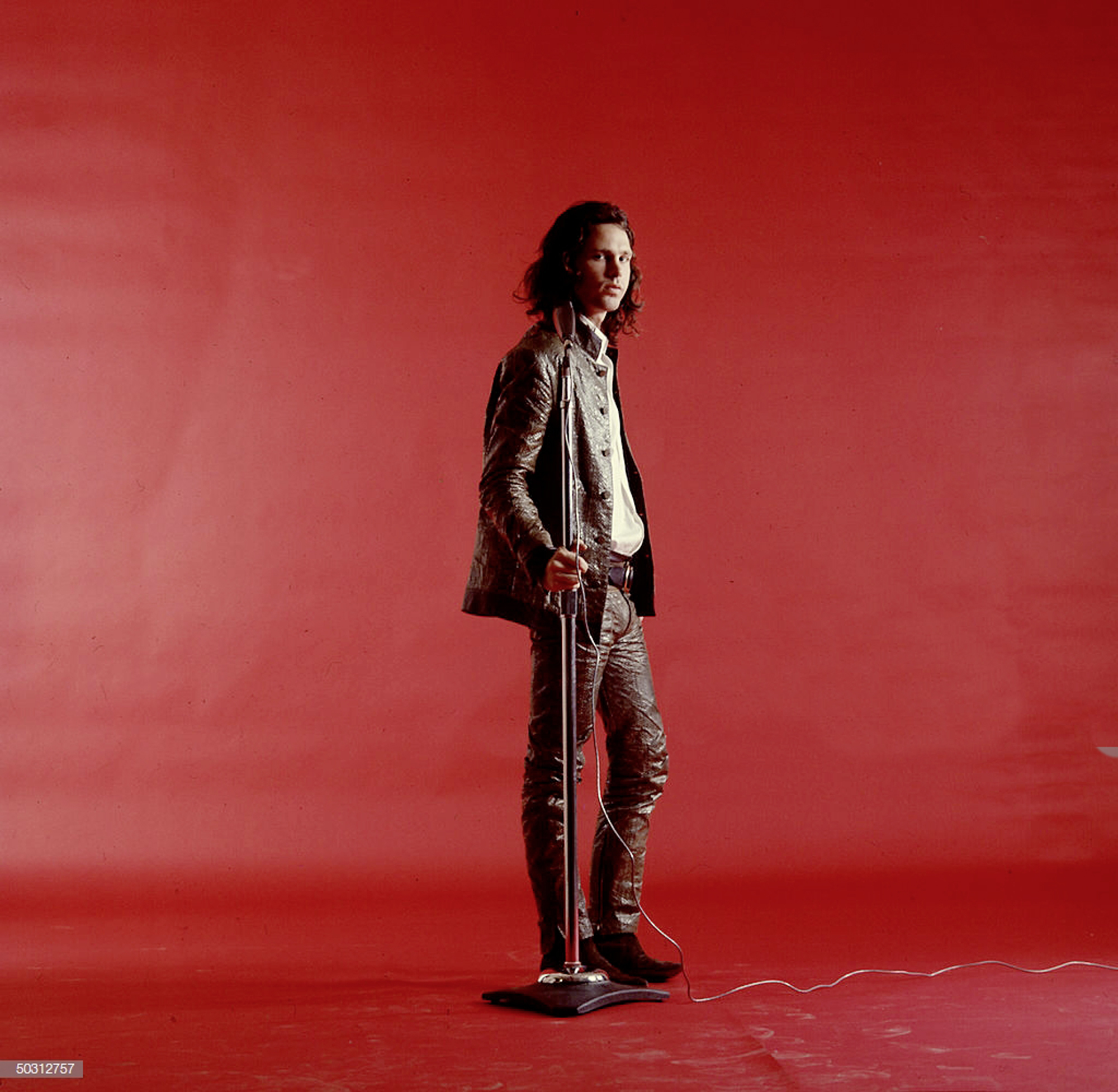

Rock star Jim Morrison of the Doors dressed in leather and standing alone next to microphone, in front of a red backdrop.

IN CELEBRATION OF THE LIZARD’S absence, new material was needed. Krieger stepped up with the delicate Yes The River Knows and Waiting For The Sun (destined not to emerge until two albums later). Morrison, meanwhile, stepped out – to the bar during lulls between vocal sessions. These had become longer, as producer Rothchild’s demands for retakes were increasing.

In a 2001 interview, the late Ray Manzarek told me he called this Rothchild’s “anal-retentive perfect recording phase. I mean, Densmore was exhausted after an evening of 20 takes of one song – like, on The Unknown Soldier, John had to do press rolls. It was like, how many times can a drummer do that? That’s a very tough time to do. So that took a long time.”

How long a time? The Doors started recording at another Holly-wood studio, TTG, in mid-February and wrapped the album in late May – three months during which they also played over a dozen gigs in the US and Canada. But if making Waiting For The Sun was a struggle, you wouldn’t know it by the strength of its contents. Hello, I Love You underscored the band’s pop chops, while The Unknown Soldier and Five To One, two fiercely rocking tracks, further defined Morrison’s rebel persona – as did his final spoken line on Not To Touch The Earth, the only segment of Celebration Of The Lizard that had made the cut. As the track fades, Jim Morrison offers his famous proclamation: “I am the Lizard King. I can do anything.”

Inside the band, however, Morrison’s behaviour was stoking tensions, and sparked an exasperated Densmore to walk out of sessions.

“This was a time before substance abuse clinics,” the drummer says today. “We didn’t know that there was a guy in the band who had a disease. But I knew that there was an elephant in the room and no one was talking about it. And one day he was down at the studio with some friends, and they were getting really sloppy, stoned, and I just threw my sticks down and said, I quit.

“But then the next morning, I woke up and said, Wait a minute, I found my path in life – music. Yes, there’s a crazy person in the band, but I cannot give this up. This is my lifeline. My blood, through music… So I went back to the studio and everyone accepted me like nothing had happened.

“But you know, I was trying to make a statement. We had actually orchestrated one meeting with Jim and Robby’s dad, and we were going to tell him, ‘Hey, you’ve got a problem.’ It was like what they call an intervention now, in modern clean-and-sober terms… but he never showed up for the meeting!”

To Bruce Botnick, Morrison’s behaviour in the studio during that era was a function of his – and the band’s – growing celebrity.

“All of a sudden they become, quote-unquote, ‘rock stars’, and this was all new to everybody,” says Botnick. “And Jim was enjoying his time. He was drunk a lot of the time. Like, you can hear, My Wild Love is a good example – he was out of his skull. But pretty much everything else, he was together. We got everything we needed from him. He was just enjoying celebrity, they were enjoying celebrity – it really didn’t impact us until after Miami. Any serious negativity – that was just, ‘Oh, Jim’s juiced again.’”

“Before, it was LSD or pot. But the minute Jim would drink too much, everything would go to shit.”

Robby Krieger

MORRISON’S ABILITY TO PROVIDE THE DOORS with “everything they needed” was crucial to them in 1968, a year that kicked into gear with the Billboard Number 1 success of the sprightly Hello, I Love You in June, which helped to propel Waiting For The Sun to the top of the US album charts in July. The Doors were in huge demand, selling more tickets than ever as they crisscrossed the States, spending more than 55 days on the road.

And Morrison’s boozing? His on-stage behaviour? Was it an issue?

“Well, we were really good,” John Densmore laughs. “Jim’s craziness was part of the allure. You didn’t know what was going to happen. Would it be wild? Would it be quiet? For that middle period we had that delicate balance of craziness and creativity, and we just were really strong.”

Robby Krieger sees it much the same way. “To tell you the truth, it all depended on how much he drank during the show. Now if he had the right amount of liquor in him, he was great, and he would do a great show. If he had a little too much, then it wasn’t so great. And if he didn’t have enough, it wouldn’t be great.” He softly chuckles at the memory. “There was a very fine line there that was kind of nerve-wracking.”

Eyewitness accounts of two consecutive Doors performances in Chicago and Detroit in May 1968 show that audience’s nerves could be wracked, too. Robert Wallace Graham was at the Chicago Coliseum show on May 10.

“We had balcony seats, and in all honesty, the balcony didn’t feel that stable,” Graham writes in his Scraps From My Autobiography blog, “but we were young and nothing could go wrong. The seats were all rickety folding chairs. This would be a mistake by the organisers, as the concert ended with some in the balcony audience (not us) heaving these chairs over the railings. I remember watching with a degree of concern and helplessness as chairs rained down on people on the main floor. I don’t remember why people were throwing them, but it was 1968 – did there need to be a reason?”

The very next day, rock photographer Thomas Weschler, then working for local music gear rental company Artist’s Music, met The Doors at their afternoon soundcheck at Detroit’s Cobo Arena.

“Jim Morrison was quite satisfied with the PA,” Weschler now recalls. “There was a feedback cancellation on the board that came with it and you could cancel the feedback. You didn’t get the full range out of the monitor speakers that way, but it was enough for him, and he liked it a lot. He treated me to a Budweiser in a can, even though I was underage.”

So he was a cool guy?

“Yeah, very cool, very nice guy. Real soft-spoken. He wasn’t, you know, weird or anything like that, until the last part of the soundcheck. He said to me, ‘Are you going to be sticking around ’til the end?’ And I said, Yeah, sure, I’ve got to take the equipment back to the store. And he said, ‘OK, good. I’m going to play a little trick on the Detroit police department. I’m going to jump off the stage, walk into the crowd, and taunt the police, and I’m going to come running back to the stage. Do you know anybody who could help me with cupped hands to get me back on the stage?’

“[Detroit/Ann Arbor local music fixture] Jeep Holland was there,” remembers Weschler, “and he volunteered. So Jeep and I were the ones who got him back on the stage. He actually jumped into Jeep’s hand and Jeep put him up, I was just there in case. But it worked out pretty well.”

SAN JOSE – MAY 19: Jim Morrison of The Doors performs at the Northern California Folk-Rock Festival at Family Park, Santa Clara County Fairgrounds on May 19, 1968 in San Jose, California.

THE DOORS ON THE ROAD WERE A CAUSE CÉLÈBRE. A good five months or so of 1968 were devoted to the shooting of Feast Of Friends, a tour documentary directed by Morrison’s friend Paul Ferrara. The film was never officially completed but saw a legitimate release in 2014, and for all its narrative shortcomings contains some eye-opening live footage of The Doors in their full glory. But back then, in summer ’68, glimpses of the band in their prime were actually rare; fans were more likely to see pictures in the local paper – of officials carting Jim Morrison away from concert chaos he had incited. Usually they accompanied news stories like this one:

NEW YORK – AUG. 2, 1968 (UPI) Three persons were injured and two were arrested today when a teenage audience at a folk rock concert charged the stage.

Police said about 200 teenagers in a capacity audience of 10,000, listening to a group called “The Doors,” began breaking up the wooden chairs at the Singer Bowl in Flushing Meadows Park, Queens.

As the group was completing its last two numbers the teenagers ran for the stage, causing the musicians to retreat, leaving their equipment behind. A witness said students armed with pieces of chairs began smashing the equipment on stage before guards could stop them.

Despite the growing and deliberate chaos – there had really been very little like it before – no one seemed to be scared off. And demand for live performances by The Doors only increased. Their European tour, two weeks of gigs and media appearances in mid-September that year, was a conspicuous success (Waiting For The Sun had peaked at 16 in the UK albums chart – their first long-player to chart here).

Most notable was the band’s performance at London’s Roundhouse, on a two-night double-bill with Jefferson Airplane. Morrison was on his best behaviour, the show was captured by Granada TV and aired within weeks as The Doors Are Open, and today its stark black and white look evokes an unmistakable feeling of musical history in the making. It – and the band – was superb.

“We were very excited to go to Europe,” Densmore remembers, “and what was it billed as? ‘The West Coast Psychedelic Sound Comes To England’ or something? It was kind of similar to the first time when we played the Fillmore West from way back – the audience just stared at us, like we were from Mars. Because we weren’t a get-up-and-dance kind of band. We were kind of dark.”

Robby Krieger says he wishes the band had returned and played more gigs in Europe. He remembers enjoying the fact that they were still relatively unknown quantities. “We went to Amsterdam,” he says, “which might have been a big mistake. Because Jim was walking around town and people were giving him blocks of hashish and stuff – and he just popped one in his mouth and swallowed it. And by the time the show came around he was not able to stand up, even. At first he was OK – in fact he ran out and jumped on-stage with the Airplane and kind of messed up their set, but then he came back and just collapsed. We thought he was going to die or something.

“So they rushed him to the hospital, and then the promoter asked the audience, ‘Jim Morrison has gotten sick – do you want to see The Doors still, the other three Doors?’ And the audience said, ‘YEAAAH, WE WANNA SEE ’EM!!’ So we went on and we played. Ray and I sang, Ray sang most of it – and it went great. And I think it was because people didn’t really know who Jim Morrison was yet. They just knew The Doors, they knew nothing about Morrison.”

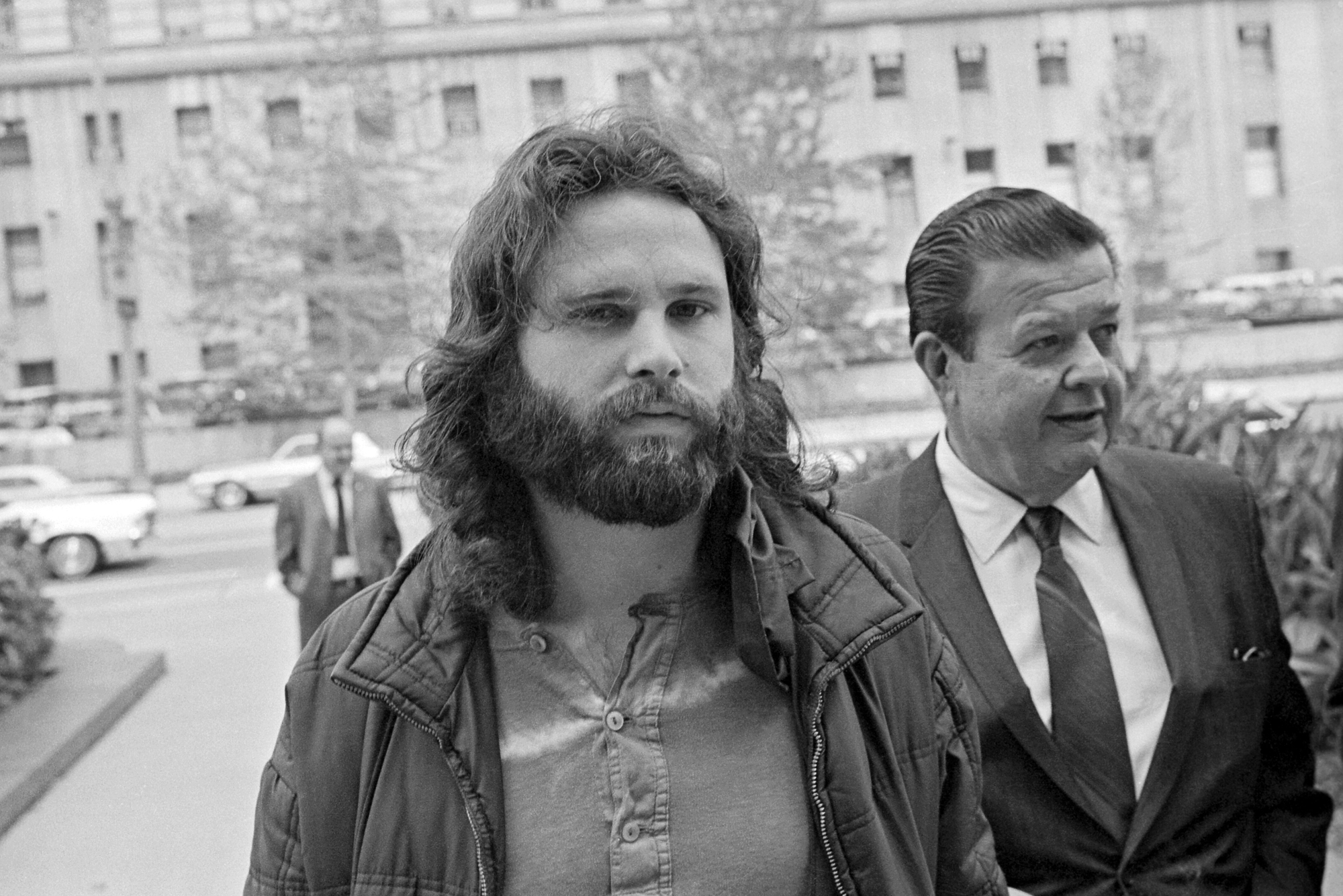

Jim Morrison (L), is accompanied by his attorney Max Fink as he arrives at the Los Angeles Federal Building to appear before the U.S. Commissioner for extradition proceedings to Florida.

ONE MIGHT THINK MORRISON’S propensity to swallow what was handed to him on an Amsterdam street corner, to drink to excess, to painfully prolong recording sessions via spontaneous partying, maybe even to incite audience riots when so moved, would inevitably break up The Doors. Or create factions within it. But no, that didn’t happen until much later in the game, notes Botnick, “when they all basically got tired of Jim being wrecked, and Jim got tired of the whole thing. And he just wanted to be left alone.”

And before that? “All the guys were really bright. I mean really, really bright. They all went to school together for the most part. Ray was incredibly smart, but very deep into cinema and religion; he knew more about world religions than most people do. And to hear an intellectual discussion and Ray and Jim – and all of them – sit around and just shoot the shit, and they’d shoot it at a very high level – was always very cool. It was fun. That was part of the thing of being with them, to partake in those conversations. They liked one another. They went on vacation together a lot.”

With profound repercussions for what was to happen next to The Doors, Morrison’s intellectual interests also included an appreciation of experimental drama. In late February 1969, he spent many nights watching The Living Theatre’s week-long series of shows at the University of Southern California in LA, including audience-challenging enactments of Antonin Artaud’s Plague, an adaptation of Frankenstein, Judith Malina’s Antigone, and more. As Krieger summarises, “it was kind of like Hair, but with more nudity.”

“So Jim went to a bunch of those [shows],” says Botnick. “And he went to Miami, and I guess he got quite intoxicated, and this was fresh on his mind, that he was going to free the audience and get one big Living Theatre going, and that’s what happened.”

Hence the audience-goading. And the penis.

“After the show, we were laughing,” Krieger notes. “We were having beers with the cops, nobody got arrested. To us, it was a successful Doors happening – even though we only played like three songs or something. We wouldn’t necessarily want every show to be like that, but it was different, it was crazy, and nobody asked for their money back. It wasn’t ’til a week later or so that some politicians started making a big deal about it, and Jim got arrested.”

“After the Miami show, we were laughing. Nobody got arrested. To us, it was a successful Doors happening.”

Robby Krieger

IF THE DOORS HAD BEEN ON A ROLL through 1968 and early 1969, Miami did slow their momentum considerably. Shows were cancelled, or not even booked; a hastily organised ‘Rally For Decency’ featuring right-wing zealot/former pop singer Anita Bryant took place at Miami’s Orange Bowl stadium within weeks; and Morrison’s name most often appeared in print with the words ‘lewd and lascivious behaviour’, ‘indecent exposure’, ‘open profanity’ and ‘drunkenness’.

“It was tough on everybody,” says Botnick. “Because you’re flying high, you’re Number 1 – and then all of a sudden you’re brought down to the ground, slammed down, and you’re blackballed, blacklisted, where you can’t do your thing. And believe me, that for any artist worth their salt – even John Lennon – you step outside what people perceive, and they don’t like you any more. And they figure you’re bad.”

‘Bad’ was one of many adjectives unkind critics used to describe The Soft Parade, the first Doors album to emerge post-Miami. It had begun its recording in November 1968 and concluded in June. Much had happened in the interim. Critics were harsh; it was not a bad LP at all, but with its strings and horns, occasional jazz solos, and a dominance of Krieger-penned songs, it seemed oddly unDoors-like.

“We had spent a frickin’ quarter of a million dollars making The Soft Parade,” says Densmore, in seeming disbelief even today. “We had to do that, we wanted to try Sgt. Pepper and the horns and strings. We got flak for changing our sound, but it was something we needed to go through.”

Fortunately for The Doors, they got through it with their very next album, Morrison Hotel. Recording began in mid-November 1969, and the album was released on February 1, 1970. It was a restatement of the band’s core strengths.

“We had plenty of time to rehearse, because we couldn’t play anywhere, we had been banned from America because of the Miami incident,” Ray Manzarek recounted. “So we went into a good period of rehearsal and composition, and the result of what came out of that was Morrison Hotel. We set out to make a hard, bluesy, album.”

However much Miami had been hanging over The Doors, the band heard on Morrison Hotel seemed rugged and carefree, tracks like Roadhouse Blues and Peace Frog resonated strongly on American radio, and touring was beginning to pick up again, although not in the conservative South. When Elektra released the first live Doors album (Absolutely Live) in July, and their first greatest hits set (13) in November, a major Doors comeback seemed in the offing.

Morrison’s post-Miami travails came to a head in late October 1970, when he was convicted on two misdemeanour counts of open profanity and indecent exposure, fined $500, and sentenced to six months in prison. While he appealed the case, he was allowed to return to LA, gathering with his band to play a new batch of Doors songs to Rothchild.

“And we played the songs, and played them badly,” recalled Ray Manzarek. “Quite badly, actually. Really dull. And Paul said, ‘You know what? For the first time in my life with you guys, I’m bored. There’s nothing I can do here, man. I’ll tell you what – if this is the album you want to make, why don’t you do it yourselves? I’m out of here.’ And we all went, ‘Holy Shit! Paul’s quit, what the fuck are we going to do?’

“And then Bruce said, ‘I’ll produce.’”

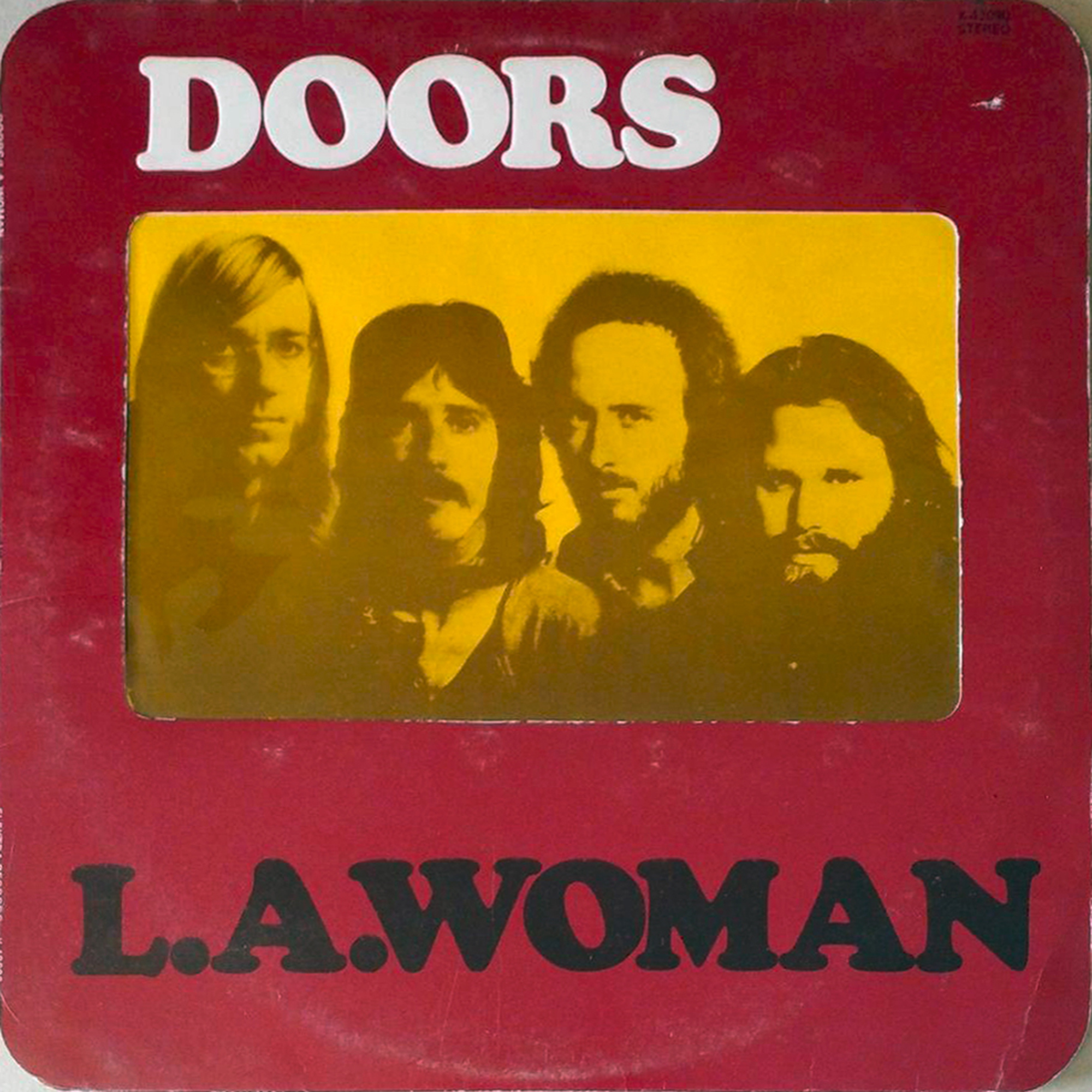

L.A. WOMAN, the last Doors album on which Jim Morrison featured.

“WITH L.A. WOMAN, WE treated it like the first album,” says John Densmore of the last Doors album to feature Jim Morrison – that is, the last real Doors album. “We made it in a few weeks, in our rehearsal room, like in the garage from the first album, we made the whole thing fast and cheap. It was your template for fuck perfection, let’s just get down to the essence of what rock’n’roll’s about, which is passion and confronting bullshit.”

In April 1971, less than two months after L.A. Woman was completed, and The Doors restored to what appeared the peak of their powers, Jim Morrison left for Paris. On July 3, he was found dead in a bathtub in a flat on the Rue Beautreillis. He was 27. There was no autopsy.

Morrison’s reckless commitment to the collision of art and life and chaos had always involved risk. But his legacy, on his own account and through the conduit of admirers like Iggy Pop, is still felt wherever the young challenge authority and performers push beyond the boundaries of what’s deemed comfortable or acceptable, where the doors to rock’n’roll fun are kicked open and everyone’s invited inside.

It may have been nearly 50 years ago, up in the steamy bleachers of Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami, and so much is hazy, but I remember distinctly the time Jim Morrison pointed at me – and my friends – and issued the official call to action:

“I can’t believe all those people sitting way over there, man,” he proclaimed, finger extended. “Why don’t you all come down here and get with us, ya know? C’mon! What are you, in the 50-cent section, or what? C’mon! C’mon down here! Get closer, man! We need some love!”

This article first appeared in issue 303 of Mojo.

Images: Getty