Mojo

Presents

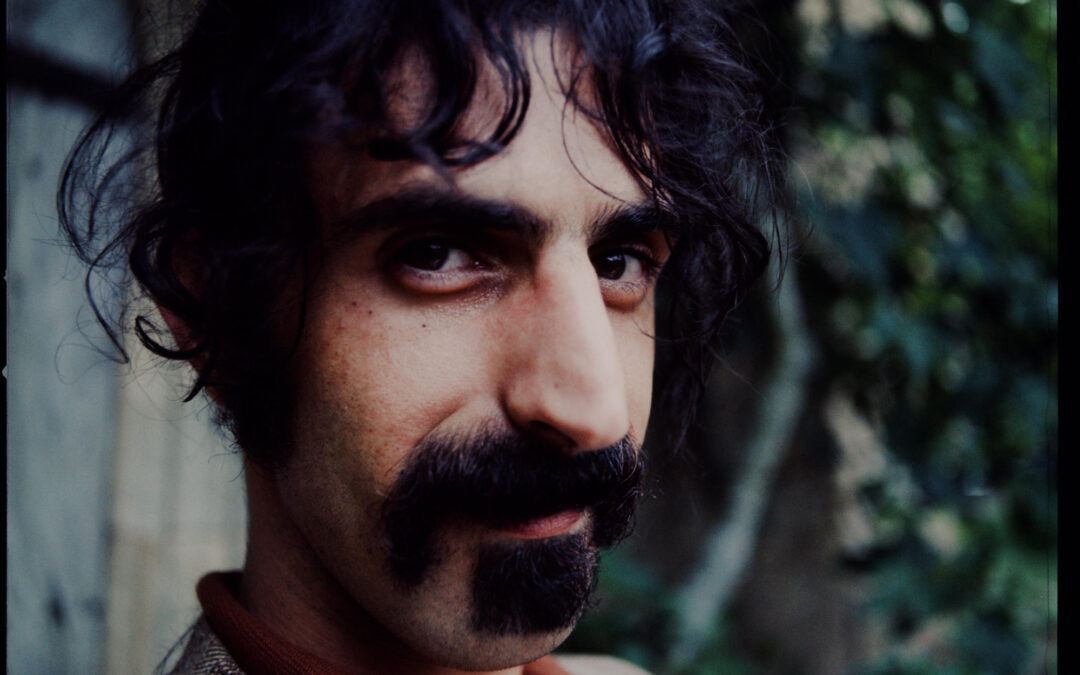

The Tao Of Zappa

MOJO goes beyond the toilet gags to immerse in the confounding life and work of Frank Zappa, and explore how a bitter contempt for conformity begat such wild creations – even, at times, beauty. “his music was eclectic,” bandmates and intimates tell Mark Paytress, “but it’s where he found his harmony in life.”

Stadio Comunale Della Favorita, Palermo, Sicily, July 14,1982: the last night of an incident-packed two-month tour and Frank Zappa was pleased it was almost over. He’d spent the previous day visiting the nearby town of Partinico, the Zappa family’s ancestral home, the place his father left decades ago on an immigrant boat in search of a better life. Walking its narrow streets, Zappa felt grateful he’d be back in Laurel Canyon soon.

“Frank would come to life on tour,” says Steve Vai, Zappa’s ace ‘stunt’ guitarist between 1980 and 1982. “He’d rent the limo, we’d go to discos. He knew how to have a good time.”

But the final weeks of this trip were cramping his style. Frank got ill, there were ancellations and too much of what he called “anti-American sentiment”, his explanation for those nights when audiences felt it necessary to throw things – in Milan, a dirty syringe – at the stage. None of this prepared him for Palermo, the Sicilian capital, which was hosting a rare major rock concert. In scenes later compared to the carnage in Apocalypse Now, police in riot gear, aided by the military, rained batons, tear-gas and bullets down on a huge crowd in a football stadium ill-equipped for such an event. It began mid-set, during Cocaine Decisions, after members of the crowd moved to get closer to the stage. A few songs later, the band quit the stage rubbing tear-gas from their eyes. What should have been a glorious homecoming ended with Frank Zappa running for his life.

“Three kids got shot and the entire audience was tear-gassed,” says Steve Vai. “It was a complete riot. Frank had to wear a bulletproof vest while we dodged between cars to get to the van because the cops were shooting. I think it affected Frank quite a bit. That’s when he decided not to tour.”

In the house along Woodrow Wilson Drive, where he’d lived with his family since 1968, Zappa was already virtually self-sufficient. He had a state-of-the-art studio, and was doing good business selling records via mail-order. And in 1983, he added a piece of kit that would keep him busy for the rest of his days: a Synclavier.

A high-end digital music system that could sample and manipulate sound, it put all the notes, all the instruments at Zappa’s fingertips. With no other musicians required, he could be anything he wanted – a one-man Mothers Of Invention (Jazz From Hell), a classical maestro (The Perfect Stranger), even an obscure 18th century chamber music composer he’d recently discovered named Francesco Zappa.

“The Synclavier made him happy,” says Ahmet Zappa, Frank’s second son and executor of his father’s legacy. “Music made him happy. His natural state was dreaming up notes.”

Frank Zappa was the most prolific and, arguably, his generation’s most gifted composer-musician, perhaps his century’s. Before his death at 52 on December 4, 1993, he’d released more than 60 albums and performed around 1,500 concerts. His famous archive, once kept in the basement of the family home (bought by Lady Gaga in 2016) and now housed in a secure, temperature-adjusted facility, is so vast that vaultmeister Joe Travers is unwilling to put a number on the tape boxes. “Just say thousands,” he advises.

“You can look at other artists who have this unbelievably prodigious output and say maybe they were just super-compulsive,” says actor-turned-director Alex Winter, who gained exclusive access to the archive for his documentary, Zappa, due later this year. “But in certain cases, like Frank, and I think Prince too, they use compulsion as a tool to drive their art.”

As for motivation, Frank always had a stock answer: “Give a guy a big nose and some weird hair and he’s capable of anything.”

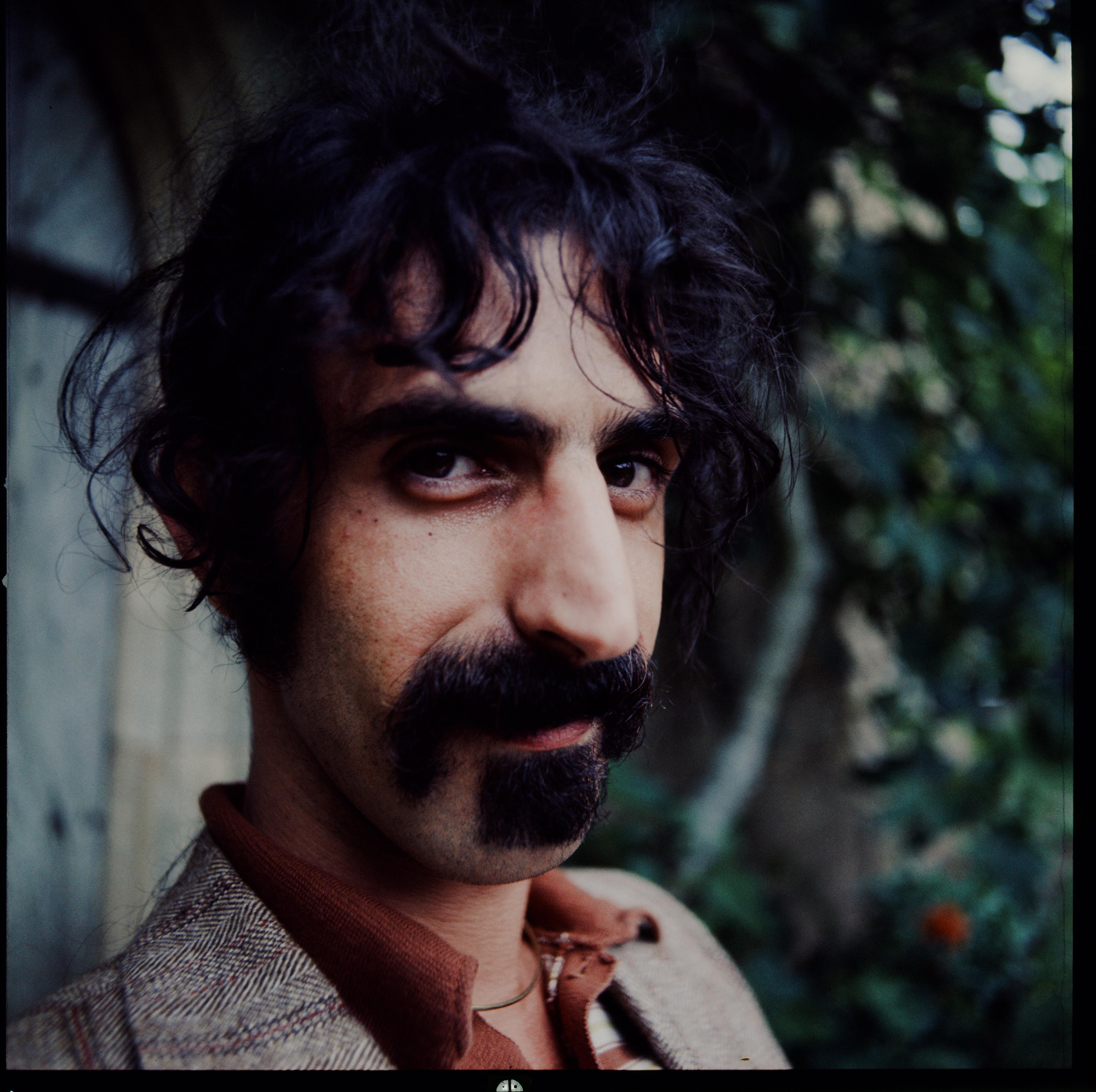

“He was so clever,” says Pauline Butcher, a secretarial temp who met Zappa during his 1967 London visit and moved to California to work for him full-time. “That was his first trip and what did he do? Put on a dress, put his hair in pigtails, wore false boobs, showed his hairy legs and had his picture taken,” she says. “It ended up on the front of Melody Maker. He didn’t mind how foolish he looked. He knew he’d get publicity over other rock stars.”

But Zappa wasn’t like other rock stars. “There was none of this layabout, hello darlin’ thing,” Butcher notes. “He spoke with such a quiet voice, and when someone speaks like that, it gives them authority. He’d also look at you with those incredible eyes and you’d be transfixed. He was very businesslike.” That could explain the ever-present briefcase. “Maybe,” adds Ian Underwood, who joined The Mothers Of Invention in 1967 and stayed for six years. “But it wasn’t for handkerchiefs. That’s where he had all his scores.”

“Give a guy a big nose and some weird hair and he’s capable of anything.”

Frank Zappa

Zappa started writing music when he was 14. It came, seemingly, out of nowhere. His father played a few crooner songs on guitar. Frank, a young home explosives enthusiast, entered his teens playing drums. Everything changed after he read a critic’s summation of an Edgard Varèse collection, Ionisation (“the worst music in the world”, is how Zappa remembered the description). “All this nasty stuff like sirens and drums,” he swooned years later. “It sounded like a good time to me.” It also helped that the dissonance sounded “really mean”.

“I don’t think it was an accident that he was interested in composers like Varèse and Stravinsky,” says Alex Winter. “There’s an enormous amount of flux and dynamism there. It’s music that’s in constant change.”

His father’s work in munitions and chemical weapons facilities took the family from Baltimore and Florida to various locations in California. Consequently, the boy with the strange-sounding surname and premature five o’clock shadow rarely settled in school. “For two weeks, they’re the number one most popular person,” says Pauline Butcher, who later lectured in psychology. “Then they’re dropped. So he became the outsider.”

In March 1965, the classroom misfit became the persecuted bohemian. For months, Zappa had run a multitrack studio in Cucamonga, mostly recording his own projects, from the odd film soundtrack to deal-seeking pop and R&B demos. He also catered for unusual requests, so when he was offered $100 for a sex tape for a party, Zappa and a go-go dancer pal faked one.

It was a sting clearly designed to teach the local freak a lesson; it landed Zappa in jail and cost him his studio. “The prison experience was seminal for him,” says Alex Winter. “That’s when he looked at the world and thought, No, I am not going to capitulate.”

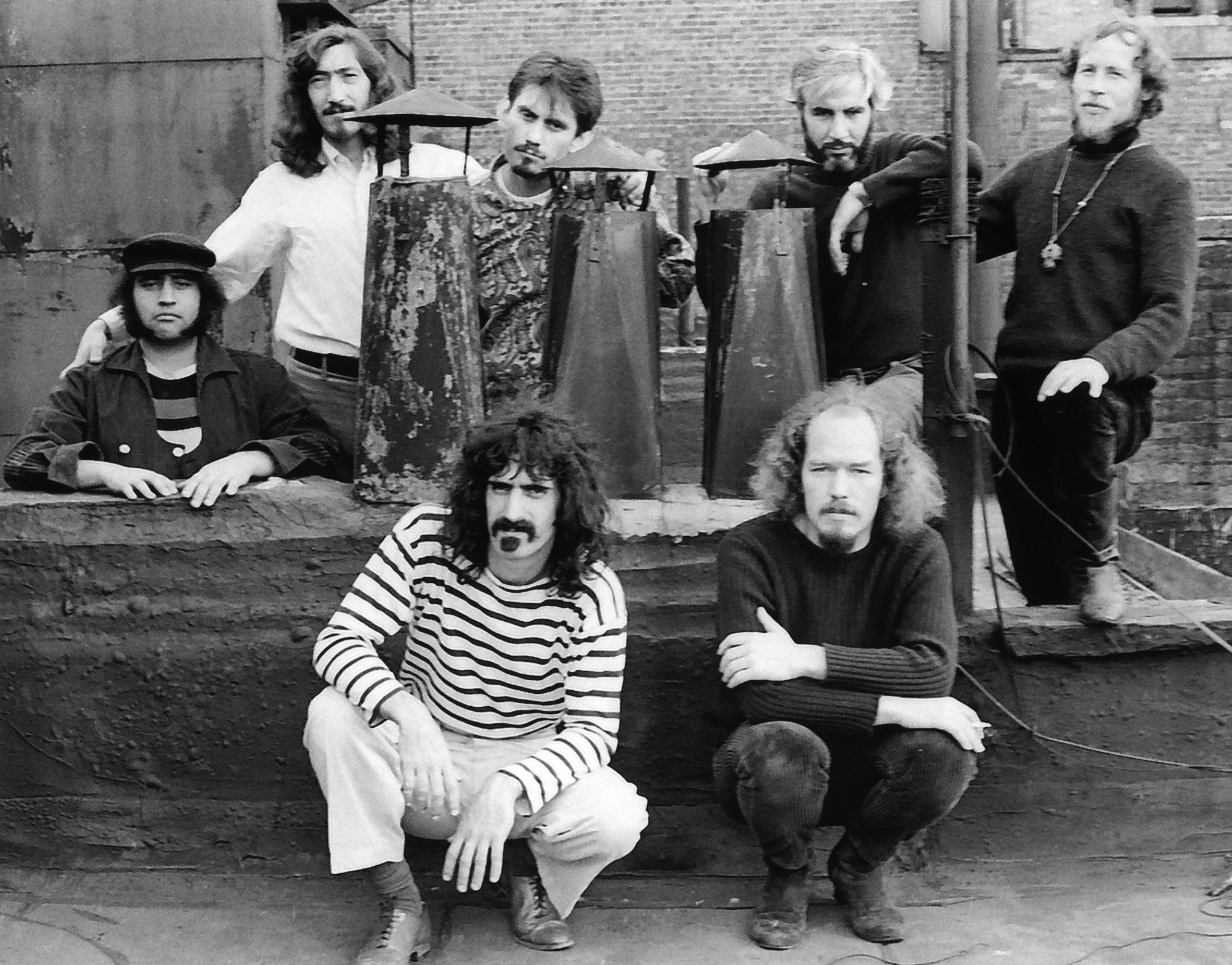

The Mothers Of Invention, a rogue’s gallery of grown men in necklaces formed weeks after the bust, were Zappa’s revenge on society. Hungry Freaks, Daddy, the first song on 1966 debut Freak Out!, savaged the supermarket world of “Mr America”. By side four – Zappa insisted on a double – the Mothers were adrift in their own musical dada-land, where B-movie yelps, groans and jungle noises were set to a drumbeat that refused to die.

After Paul McCartney heard it, he demanded The Beatles record a ‘freak out’ LP; a young David Bowie was hooked, adding the potty a cappella It Can’t Happen Here to his 1967 live set.

By 1968, Zappa had become a leading counterculture figure, acclaimed for the originality of his music and his articulate outspokenness. To Life magazine he was the “oracle-philosopher of the rock scene”. Yet despite the unprecedented, genre-mashing brilliance of albums like Absolutely Free and We’re Only In It For The Money, the defiantly drug-free Zappa was a divisive voice on the underground. “Everybody in this room is wearing a uniform and don’t kid yourself,” he told an audience of longhairs early in 1969. Middle America was never his sole target.

Having become frustrated by hippy convention, Zappa was also outgrowing The Mothers Of Invention. In August 1969, citing the high cost of keeping up to nine musicians on the payroll, he disbanded the group that had stood by him for four years. “They were brokenhearted,” says Pauline Butcher. “It was like a divorce for them.”

The only survivor was Ian Underwood. A reeds and keys player who’d graduated in composition at Yale and Berkeley, he was the nearest to a musical accomplice Zappa ever had. “Maybe I was his Synclavier,” Underwood says, “a useful tool.”

Village Voice journalist Sally Kempton noted the pair’s easy rapport at New York’s Apostolic Studio over winter 1967. “You’re going to have to do the parody notes more staccato, Ian,” says Zappa from the control booth intercom. “You want a little bebop vibrato on that, too?” Underwood asks, presumably on sax. “Yeah, a little bebop a go-go,” says Frank. By the time engineer Dick Kunc presses the record button, Zappa was “bent over a music sheet writing out the next piece.” It was one in the morning.

Zappa couldn’t stop. By 1969, he’d also stockpiled a menagerie of freaks and outsiders for his labels, Straight and Bizarre Records.

“It was bittersweet being around Frank,” Alice Cooper guitarist Michael Bruce once told me. “He was a music Nazi – an amazing musician but always ordering people around. We were viewed as one of his creations. We wanted to do our own thing.”

Zappa’s relationship with his old high school pal Don Vliet, alias Captain Beefheart, was more complicated. “They used to go to movies together and look for the zippers on the monsters,” Magic Band drummer John French told me last year. “They both had this jaded view of life.”

“Beefheart was this weirdo who talked gibberish,” adds Pauline Butcher, who sat in on several late-night conversations between the pair. “Frank was a straight bloke who always acted superior when they were together.”

Another Straight act, certified paranoid schizophrenic Wild Man Fischer, was still bemoaning his one-time mentor’s apparent neglect in 1981. “Frank’s got money in the bank,” he yelled on Pronounced Normal. “Frank’s got women he can spank.”

“Nothing was taken too seriously, but it was very serious.”

Steve Vai

Zappa had a manipulative streak. He could also hit musical highs that, says Ian Underwood’s Julliard-trained, marimbaplaying wife (and fellow Mother) Ruth, stand comparison “with the greatest cello expressions and choral music”. She singles out his guitar playing on Holiday In Berlin, Full Blown from 1970’s Burnt Weeny Sandwich. “He’d do that night after night,” she says of his wah-pedal showcase, “getting into that space as if he’s hypnotised. But he was always in control. He always knew where he was going.”

It was that extraordinary sense of purpose, as much as anything else, which prompted his decision to drop the Straight acts and split the Mothers. But, says Ruth, he also had a well-tuned instinct for “the Landscape: the political climate, the sexual things a certain age group might do, what music people listened to and why – and what the regulations are.”

It was clear to Zappa that the ‘anything goes’ of psychedelia had lost its allure, that rock musicians were now polishing their skills, making considered career moves in anticipation of the new decade. In cahoots with Ian Underwood, he put together a small-scale group project, fronted up by guitar and horns blazing an explosive, mostly instrumental jazzrock trail. The resulting Hot Rats, issued in October 1969, established Zappa as a serious contender in the grown-up, here-to-stay rock scene.

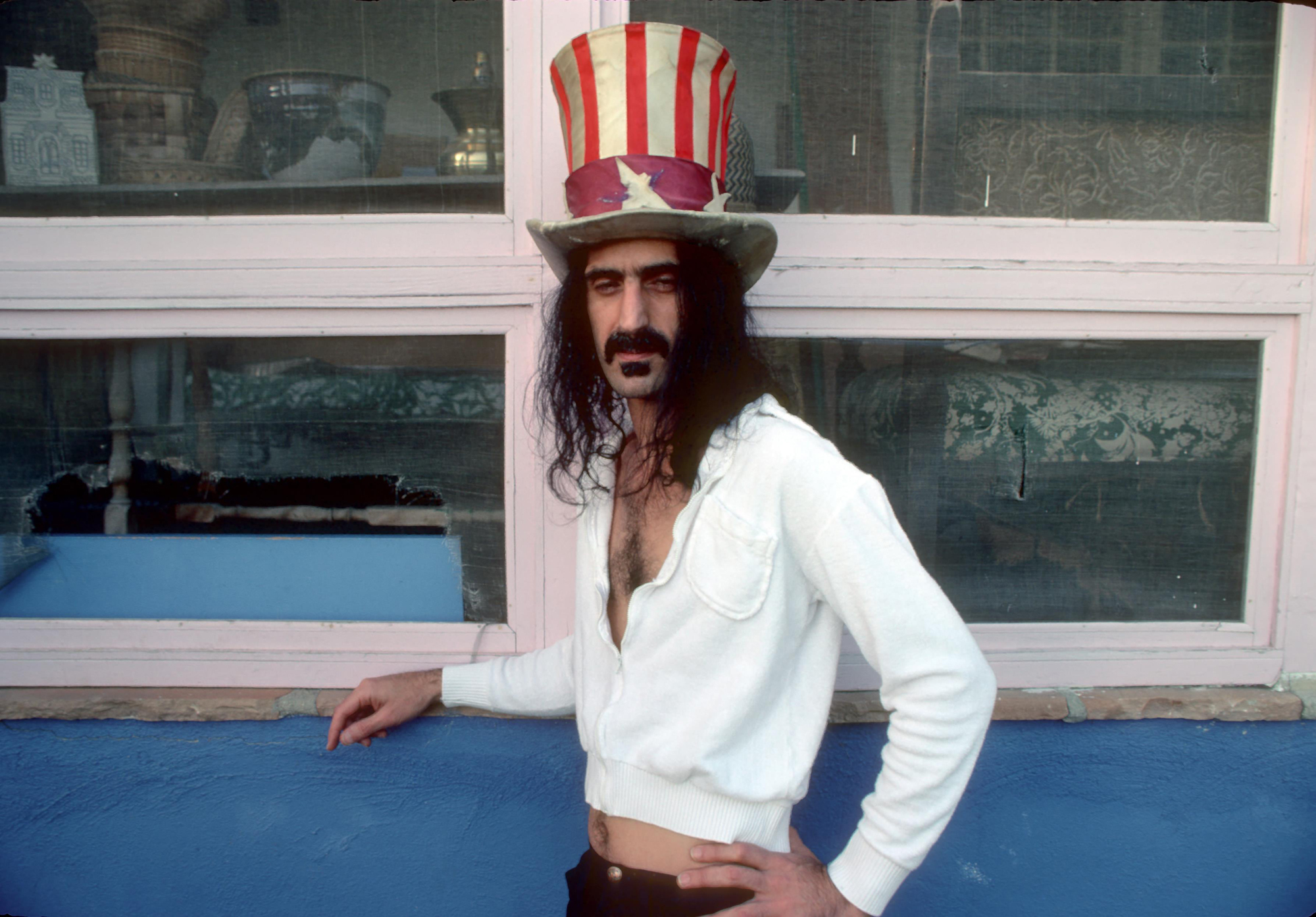

Yet, near pathological in his desire to confound, Zappa refused to stay in that space for long. After a handful of gigs with the Hot Rats group during winter 1969/70, Zappa hired two accomplished crowdpleasers, ex-Turtles Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan (alias Flo & Eddie), revived The Mothers – the ‘Invention’ appendage was dropped – and went vaudeville. Those dazzling feats of virtuosity hadn’t gone away, but it was the lurid tales of on-the-road sexploits that seemed to find most favour with rock fans.

“That’s absolutely fundamental to who he is,” says Alex Winter. “Zappa liked dirty jokes, liked shitty horror movies, loved saucy perspectives. He knew if you contrasted that with very serious music, it would fuck people’s brains up.”

Speaking to Time Out in 1971, Zappa insisted he was merely reflecting “the general atmosphere of this age”. He neglected to mention his own bulging ‘research’ portfolio of groupie encounters. “He had a girl in every port but didn’t allow [wife] Gail to blink an eyelash at another man,” says Pauline Butcher, still unimpressed.

A feature film, 200 Motels, with Ringo Starr playing the part of Zappa, confirmed Zappa’s creative hunger and ambition. It was also quintessentially, uncompromisingly, infuriatingly ‘him’, the score drawing comparisons with Stravinsky, but with words that touched on penis size and crotch deodorising. On the eve of a February ’71 tie-in performance, featuring the ‘Flo & Eddie’ Mothers with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Royal Albert Hall banned the show on the grounds of obscenity. Frank railed at the iniquity of it all, but little harm was done, for this was summertime for Zappa, a figurehead for the emerging, sexually liberated generation. Then: what Ruth Underwood calls “The Catastrophe”.

On December 4, 1971, a fire broke out during a Mothers set in Montreux, Switzerland, destroying the band’s equipment. Six days later, a member of the audience attacked Zappa on-stage at the Rainbow Theatre in London. Frank fell 10 feet into the orchestra pit. His assailant claimed he did it because his girlfriend “loved Frank”.

“I had a broken rib, a broken shin tibia, a giant hole in the back of my head [and] the side of my face got mashed in,” Zappa told Sounds’ Steve Peacock the following September. For three weeks, no one knew whether he’d suffered brain damage – or if he could play guitar again.

“I don’t think he was the same afterwards,” says Ruth Underwood. “The dynamic changed. He had a bodyguard and he was The Boss. Of course, we all knew that anyway…”

Zappa valued personal freedom above all other things, so his anger would have been considerable. But he was also someone who dealt in practicalities rather than ‘what ifs’. “The next thing I knew,” says Ian Underwood, “he was writing all this music for big bands.”

Drummer Aynsley Dunbar, a Mother since 1970, was unhappy about the creative shift. After playing on Zappa’s 1972 recovery projects, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, he quit. “I just had to play something simple for a while,” he explained.

For Ruth Underwood, now lined up alongside violinist Jean-Luc Ponty and keyboard player George Duke, the virtually all-new lineup unveiled in 1973 marked a new beginning. “Frank had the power of regeneration more than anyone I have ever known,” she says. “Just when you’d think the guy was finished, he’d come up with something extraordinary.”

To assist him in that quest, Zappa took The Mothers out on a short tour alongside John McLaughlin’s fusion supergroup, Mahavishnu Orchestra, hailed as the most supremely accomplished band to grace a rock stage. “It freaked Frank out tremendously,” Ruth says. “We were great. But we were not the only greatness in the room.”

Mahavishnu’s work was guided by spirituality. By contrast, Zappa believed in the divine right of throwing everything into his music. “Crazy guitar playing, deep compositional elements, huge beauty in the melodies but also incredible dissonance,” says Steve Vai, who’d discovered Zappa’s work as a young teenager around this time. “Plus the unexpected, which I love the most. Nothing was taken too seriously, but it was very serious.”

Three mid-’70s studio albums, Over-Nite Sensation, Apostrophe (’), One Size Fits All, and live double Roxy And Elsewhere, represent a peak, especially among Zappa musicians. “He had a band that could do everything,” says Ruth Underwood. “He could be off-colour with what we called his ‘folklore’. Then we’d be playing some absurd polyrhythm which would blow your head back.”

“Just when you’d think the guy was finished, he’d come up with something extraordinary.”

Ruth Underwood

On June 24, 1991, at the invitation of Czech President Vaclav Havel (who, like many behind the old Iron Curtain, regarded Zappa’s work as a defining symbol of freedom), Frank went to Prague to perform at a concert to mark the final withdrawal of Soviet troops. It was one of the proudest moments of his life.

“This is just the beginning of your new future,” the already ailing Zappa told the massive crowd. “But please, try and keep your country unique.” His words were carved from experience, spoken from the heart.

Little over two years later, Frank Zappa was gone.

“I’ll tell you one last thing,” says Ahmet Zappa. “My mother and father really loved that book [Benjamin Hoff ’s] The Tao Of Pooh. They’d often have these back-and-forth conversations about it.” The book’s central character, Winnie The Pooh, represents the Taoist philosophy of wu wei, or ‘effortless doing’.

“You know, I never saw Frank struggle while he worked,” says Ian Underwood. “It was like watching Picasso walking over to an easel and making a few gestures with his brush, or a beetle crawling up a leaf. You’d just think, Isn’t that the most awesome thing ever?

Auditioning for Zappa in 1975, drummer Terry Bozzio got a pre-release blast of One Size Fits All from his new employer.

“I wish I could have played more of that stuff,” Bozzio says, “but Frank wanted to move on to something new.”

The old band had fallen away, mostly through exhaustion. “Ian and I made a pact that we were not going to mention Frank Zappa’s name in the house,” says Ruth Underwood, who quit at the end of 1974.

Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention

The late 1970s were strange, potentially difficult times for Frank Zappa. A fall-out with Herb Cohen, his manager since 1965, created complications with Warner Brothers; 1976’s Zoot Allures would be his last bona fide new studio album for three years. Zappa took flight. For two years, he toured the world with a skills-packed bunch of whizz kids, including scholarship prodigy Bozzio, conservatory-trained Peter Wolf and guitar trickster Adrian Belew. The music was demanding and exhilarating. Song titles such as Titties & Beer and I Promise Not To Come In Your Mouth sold them short.

To the new punk rock crowd – including Sniffin’ Glue editor Mark Perry, whose band Alternative TV covered a 1967 Mothers Of Invention A-side, Why Don’t Cha Do Me Right – Zappa had become as cloth-eared to cultural change as those “vegetables” he’d savaged early in his career. Yet, like fellow dinosaurs Pink Floyd, he enjoyed a huge career bounce once punk’s initial shock had been absorbed.

“It’s a pretty coarse culture,” Zappa told Oui’s Dave Rothman in April 1979, responding to concerns about “blatant sex” in music. He’d just released Sheik Yerbouti, his first for Phonogram and a million-seller, partly due to the success of seedy single Bobby Brown. It wasn’t his function to elevate the tone, he insisted. “That’s like going to the North Pole and trying to find a French restaurant.”

His irascibility masked a Frank Zappa who understood how lonely that might feel. “Most of the time Frank was wonderful to be around,” says Bozzio, who left the band in 1978. “We’d ride in the smoking car even if we weren’t smokers just to be next to him. But on the last two weeks of a tour, things would change.

“First, the non-smokers would disappear into the other limo. Then the smokers. One night, the whole band and crew were standing in the luggage van just to avoid Frank’s mood. As he pulled away in one of those [stretch] Mercedes limos, you could see him right in the back with that little black cloud around his head. He couldn’t put up with the sameness of it.”

Back in Laurel Canyon post-Palermo, Frank Zappa, now 41, felt the cloud lift. His recent success had paid for his new studio, the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen. After a long battle, he was now in control of his masters. And he’d launched a series of mail-order albums of his guitar solos. As the first major artist to secure his own independent power base, Zappa now basked in an enviable degree of separation from the music industry. All that, and his own useful idiot, the Synclavier. “You push a button and you get a finished composition,” he declared. “Every composer’s dream.”

Pauline Butcher remembers late ’60s Zappa as a man who ate alone and hid the television in a cupboard. Now a father of four, he was much more fun.

“I had the happiest childhood,” says Ahmet Zappa. “Every meal was storytime. All the decisions they made as parents were to give us more options and to cultivate our individualities. He cared deeply.”

Ahmet calls his father ‘The Mugician’. “He was like a musical mad scientist,” he says. “One Fourth of July we were listening to the fireworks going off in the Canyon and he put the microphones out. It was like he was hunting for invisible animals.”

At the optimum moment of his hard-won freedom, Frank Zappa watched those Independence Day pyrotechnics fade and feared for the future. “Whatever happened to music?” he quipped to an MTV jock in 1984, well aware of the irony that the channel had played a significant part in making music subservient to “visual merchandising”.

He was even more despairing of the Reagan administration’s trend towards “fascist theocracy”. So when, in 1985, the Parents Music Resource Centre, fronted by what he called “deranged housewives of Washington DC”, began to bang the drum for censorship in music, he pulled on a suit and testified at a Senate hearing on ‘porn rock’.

“He’d made a decision very early on in his life to commit himself to music,” says Alex Winter. “And he refused to be quiet by fighting for the rights of other musicians who weren’t even fighting for themselves.” Despite Zappa’s bravura appearance and defence of the First Amendment of the US Constitution, those ‘Parental Advisory’ stickers began popping up everywhere – even on his own Jazz From Hell, an instrumental album.

Zappa, who’d been tempted back on tour during 1984, returned for one last outing in 1988. The band, a 12-piece, was on fire – both out front and backstage, where bitter disagreements among the musicians forced Zappa to cancel the final dates. He had better things to do: namely, The Yellow Shark, a collaboration with the Ensemble Modern and the best of all his intermittent orchestral works. At the premiere in Frankfurt, on September 17, 1992, Zappa received a 20-minute ovation.

“He was aware of the existence of another side of music,” eulogised 20th century classical music institution Pierre Boulez, who collaborated with Zappa in 1984. “[And] he wanted to invent something of his own.”

“His music was eclectic,” concludes Ruth Underwood, “but I believe it’s where he found his harmony in life.”

This article first appeared in issue 321 of Mojo

Images: Getty