Mojo

FEATURE

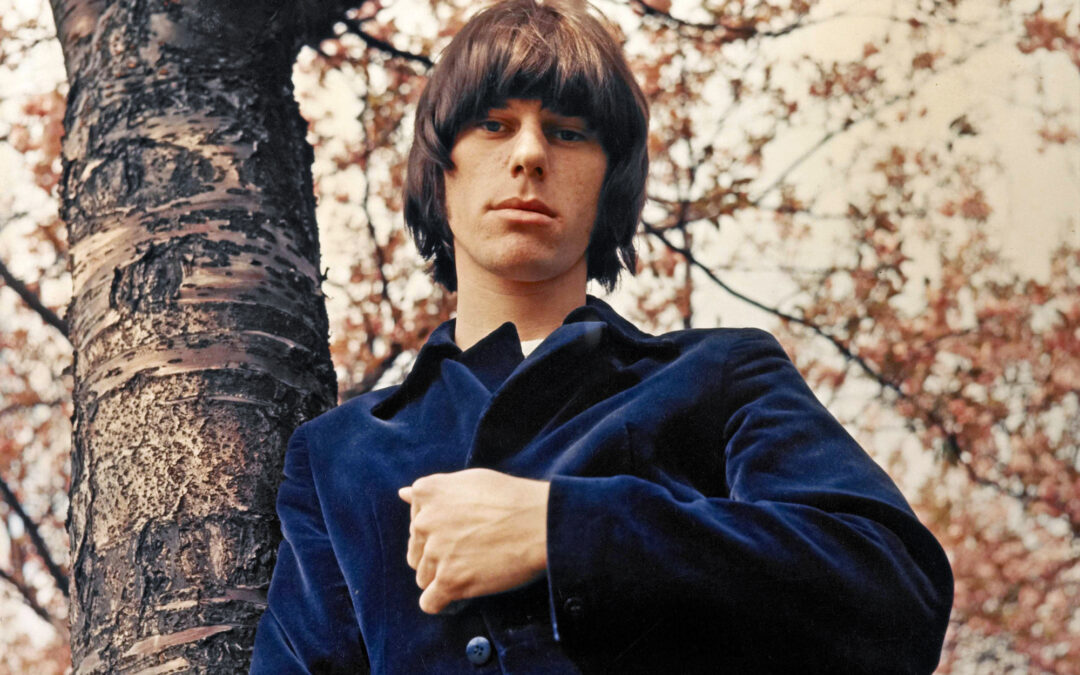

You better believe

Jeff Beck made the guitar do things no-one had imagined, let alone heard before. And while other axemen of his pioneer generation were more loudly lauded, he was the one who kept moving, kept growing, right until his sad passing in 2023. If that went under the radar, that was just too bad. “Jeff had a mystique about him,” discovers Mat Snow. “He didn’t give it all away.”

Written by Mat Snow

In any artist’s life, there’s often talk of a moment, an epiphany, which sparked the whole creative journey.

Jeff Beck revealed his epiphany on an American TV show devoted to his most fervent passion.

Not music, nor even guitars: cars.

In 2009, when Car Crazy came to film on his East Sussex spread where he stabled the collection of hot rods and custom cars he’d rebuilt himself, our host recalled his uncle taking little Geoffrey for a tear-up in his MG, getting up to all of 75mph, whereas in the family car his dad never pootled above 45. The MG also had that rare extra, a radio, which sat tantalisingly silent until Geoffrey, fiddling about as small boys do, switched it on and out burst music such as he’d never heard before: the blues.

His outraged uncle flicked it off, and the next time Geoffrey was taken for a spin the radio had gone.

It’s all there: speed, excitement, fun, music, America, the forbidden. Though rock’n’roll was yet to come, featuring his absolute favourite player, Cliff Gallup of Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps, young Geoffrey was already besotted with the hits of electric guitar pioneer Les Paul, despite his Brahms-loving mum’s disdain. “She’d say, ‘That’s all tricks,’” he told writer Dave Thompson, “but it caught my ear straight away because of its astonishing speed and a slap echo – this great sound dimension that hit me for the first time in my life. After post-war austerity, this was all I needed.”

Small wonder that Geoffrey Arnold Beck sold his soul to the devil on the A3 Kingston bypass to become the legendary Jeff, perhaps the only electric guitarist ever to inhale the same stratospherically rarefied empyrean of brilliance breathed by Jimi Hendrix.

Cal Danger and the Dangermen (L to R: Jeff Beck, Cal Danger, George Clarke, John Owen) outside the High Court in London where they are being sued by Gene Vincent, on September 12th, 1961

Serial winner of every guitarists’ poll to name the best of the best, Jeff Beck became famed not just for his instrumental prowess but also for his habit of hitting the off-ramp on fortune’s highway just as the seriously big time loomed. When he died on January 10 aged 78 of bacterial meningitis, he had not quite the instant brand recognition of the guitarist whose gig he took over in The Yardbirds in 1965, Eric Clapton, nor even of his old pal who succeeded him in that spot, Jimmy Page. Most of the time he seemed happy with that connoisseur status – but not always.

“I feel undervalued,” Beck told the Live Aid impresario Harvey Goldsmith in 2008 when he phoned asking if he’d take over his management. “I said, You are undervalued because you don’t do that much,” Goldsmith recalls. “He was tinkering and enjoying life. He wasn’t unhappy about things, but just felt musically he could be doing better. He felt it was his turn.”

Beck didn’t always feel the need for validation; indeed, rather than making, touring and promoting his music, he seemed happier to disappear under a custom ’32 Ford Coupe. As Beach Boy Al Jardine joked back in 2013 when, to some surprise, the guitarist joined him and Brian Wilson on tour, “He probably has the biggest collection of little Deuce Coupes in the world.”

“He was very modest,” says Goldsmith. “He never understood his fame at all. He never thought that he was a big rock star and could do whatever he wanted. He was terribly humble. And that was part of the problem.”

For so nimble-fingered a guitarist, Jeff Beck was an all-thumbs careerist, albeit one who escaped ‘Net Curtain Land’ – Wallington in Surrey, one of the ring of London satellite towns which birthed British blues-rock in the ’60s – to Swinging London and, from 1976, a Tudor manor house sitting in 80 acres of land in Wadhurst, East Sussex.

Just as his fitful career (not helped by tinnitus since the ’80s) lacked a shapely narrative arc, over the decades he’d tinker with his story so you could never be sure of why he did what he did and when; you sense he wasn’t even sure himself.

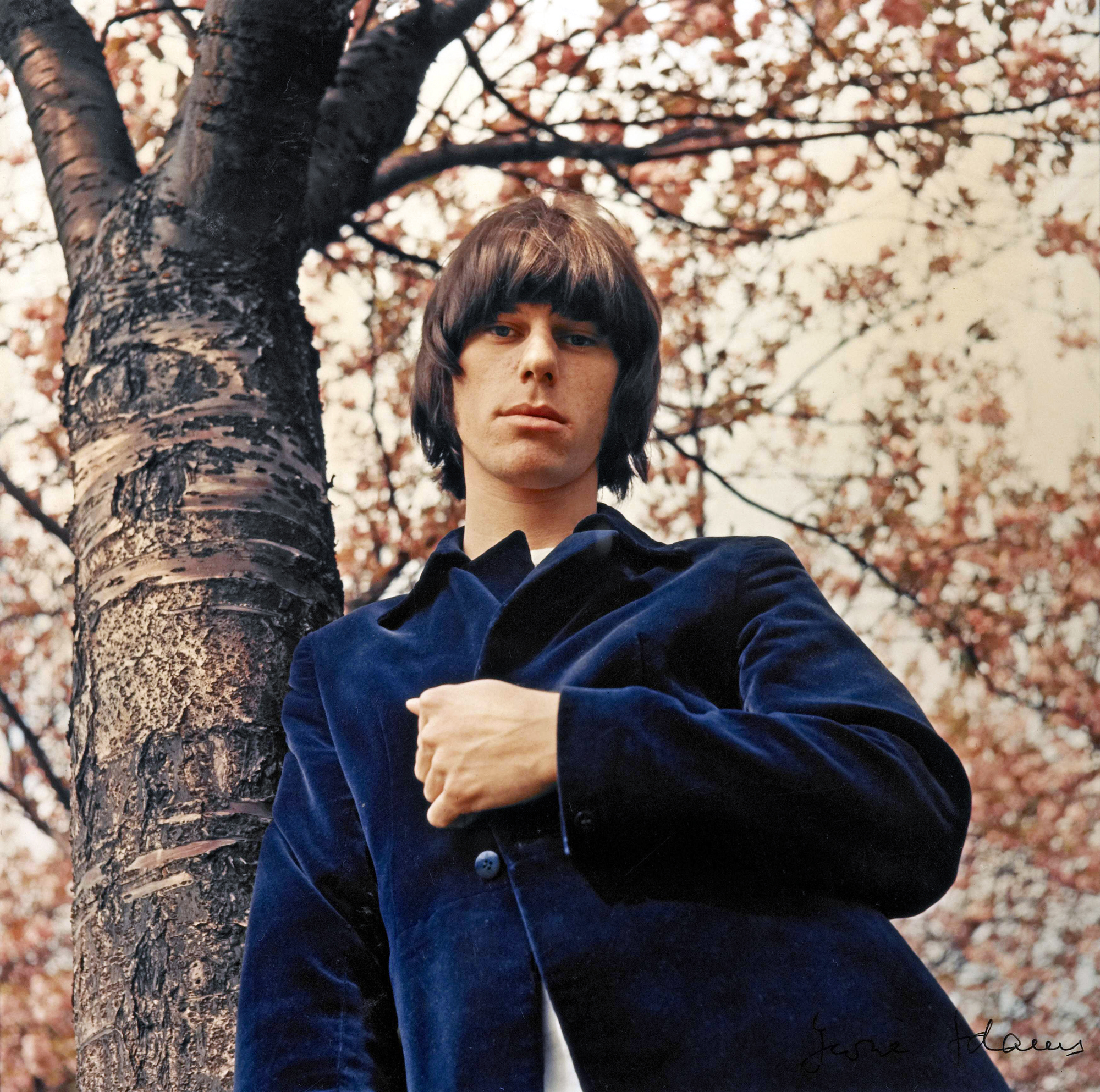

“The Yardbirds” pose for a portrait in 1965. (L-R) Jim McCarty, Jeff Beck, Paul Samwell-Smith, Chris Dreja, Keith Relf

“He was very modest. He never understood his fame at all. And that was part of the problem.”

Harvey Goldsmith

It had all started so well. With the British R&B boom in full swing in early 1965, his band The Tridents were on the up when the far bigger Yardbirds came knocking. Lead guitarist Eric Clapton felt The Yardbirds’ choice of material was deviating from the pure path of the blues and had quit; the gig had been offered to Jimmy Page but his studio session career was too lucrative to gamble away on the promise of pop stardom, so he recommended Beck.

For 18 months Beck turned the band upside down with his guitar pyrotechnics, drawing on such eclectic inspirations as Dutch synth pioneer Tom Dissevelt and Indian and European classical music as well as the ’50s rockers and pickers and Chicago’s South Side blues men; from Heart Full Of Soul to Happenings Ten Years Time Ago, you hear Beck blossom into rock’s most spectacular guitarist.

Then, in the throes of illness, nervous breakdown, true love or “something good on television” – his explanation changed over the years – he blew out gigs and got the heave. At the same time, late 1966, Jimi Hendrix flew in from New York, saw what Beck was doing and took it higher, further and deeper. “He was doing things so upfront and unchained,” Beck said. “That’s what I wanted to do, but was British and a victim of the class system and poxy little schools.”

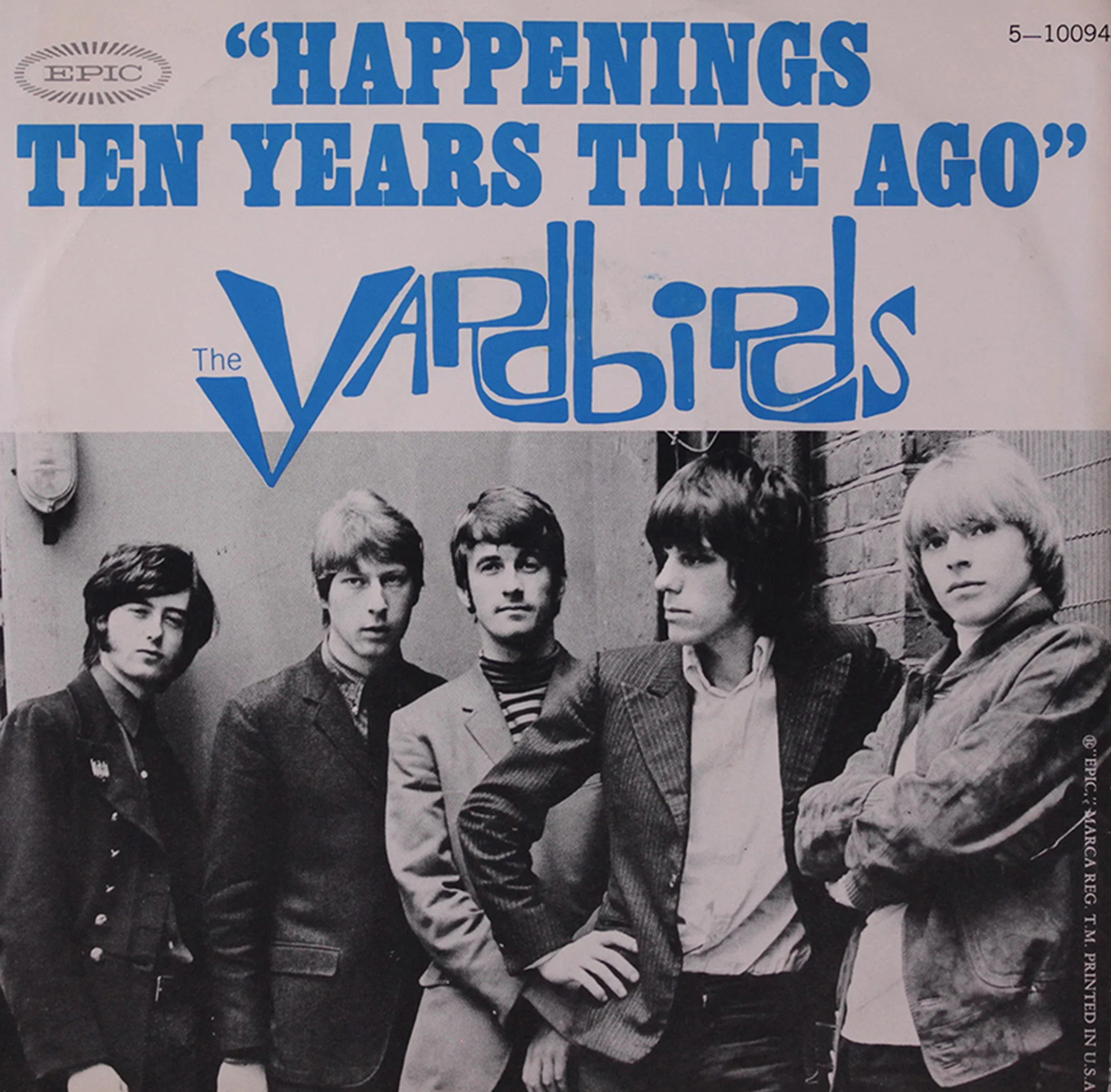

A little lost, Beck reluctantly fell in with pop svengali Mickie Most, who rebooted the guitarist into a solo star with March 1967 single Hi Ho Silver Lining – the singalong hit Beck would struggle to live down. A year later, The Jeff Beck Group – featuring Rod Stewart on vocals and Ronnie Wood on bass – blueprinted swaggering heavy blues-rock with a side order of pastoral prettiness on the album Truth and toured America with great success. Yet with 1969’s Beck-Ola in the charts and wind in their sails the guitarist broke up the band just a fortnight before they were due to appear at Woodstock. Again, a host of reasons have been suggested, by Beck and others: ego clashes with Stewart and Wood, fears that Sly And The Family Stone would upstage them or that a poor performance would be preserved for posterity on film.

After a car accident kept Beck off the road for 18 months, he resurfaced with The Jeff Beck Group Mark II, but, despite the excellent keyboardist Max Middleton and funkier spin in thrall to his beloved Motown, both material and musical chemistry fell short. Things only got worse when Beck realised his long-held ambition to team up with the Vanilla Fudge rhythm section in Beck, Bogert And Appice. Again, ego problems and dissolution followed, but also, perhaps, the belated realisation that he was really no bandleader.

“Jeff didn’t really care about me and Ronnie,” Rod Stewart recalled of his Jeff Beck Group stint in 2013. “Sometimes Ronnie and me wouldn’t get paid for weeks and we’d have to go stealing eggs, poncing breakfast off Jimi Hendrix’s girlfriend. But I cannot overstate how much I learned musically with the minimal line-up of that band, guitar and voice playing off each other.”

Learning the same lesson in the wings at those 1968 JBG gigs was a more natural bandleader: Jimmy Page. Years later Beck told Tom Hibbert, “When Led Zeppelin made it so big, I was absolutely jealous as hell. But,” he added, “I’m glad I carried on as I was. I personally couldn’t have put up with that mass adulation.”

At which point, fate intervenes.

In 1973 Beck had met keyboardist Jan Hammer, when the latter’s band, fusion trailblazers The Mahavishnu Orchestra led by guitarist John McLaughlin, were playing in Zurich at the same time as Beck, Bogert And Appice. Beck and Hammer bonded over a shared love of Marvin Gaye, whose sensuality each felt was lacking in their own bands. “I thought we could put more funk and feel into the music, and Jeff was right into it,” Hammer recalls. “He was coming from the rock world and I was coming from the so-called jazz world, and our paths crossed exactly at the right time to influence each other.”

On Beck, the influence was colossal. He set out to make his own fusion album, balancing dazzle with sensuality. “With John [McLaughlin], the playing was cosmic, like mercury,” says Hammer. “Jeff’s playing and sound were much more like a voice, very human, a loving, caressing sound even though he could turn it on and crank it out with the best of them. John was like Coltrane and Jeff more Stan Getz.”

Tal Wilkenfeld, the bass virtuoso who joined Beck’s band in 2007 aged only 20, agrees that Beck was a singer manqué. “We’d be riding in the bus listening to music, and the first thing he’d comment on was the lyric,” she says. “And if it was instrumental, it was about the meaning of the song, the purpose behind it, not just playing for the sake of playing.”

Jan Hammer playing keyboards supported by Jeff Beck at the Ronnie Lane ARMS Benefit Concert at Madison Square Garden, New York

With Beck singing through his guitar (literally so via a vocoder-like talk-box on a cover of The Beatles’ She’s A Woman), 1975’s Blow By Blow was an instrumental album produced by George Martin, and an instant classic. Critical to its success was what was to become Beck’s signature ballad. In 1972 Stevie Wonder had invited Beck to his sessions for Talking Book (that’s Beck on Lookin’ For Another Pure Love). Tinkering on the drums, the guitarist came up with the pattern on which the 22-year-old auteur would build Superstition. Whether Wonder intended the song for Beck is unclear – Beck would later say that Wonder’s record label, Motown, were the ones to insist that Wonder release a version first – but recompense, if that’s what it was, was sweet. Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers – a song Wonder wrote for his ex-wife Syreeta Wright – took pride of place on Blow By Blow, and became the first of many reflective numbers that revealed Beck’s exquisitely tender side.

Jan Hammer came aboard for Wired, the 1976 follow-up again produced by George Martin, and they collaborated on and off for the rest of Beck’s career. “I’m walking through the house where we recorded a whole chunk of Wired and especially the tune Blue Wind which was really just the two of us,” he sighs over the phone from New York. “I’m looking around and I’m pretty emotional about it.”

All of Beck’s musical collaborators whom MOJO spoke to have been hit hard. They all attest to his youthful energy, curiosity, mischievousness and hunger for exploring new musical worlds; this was not a musician nor man anywhere near the end of the line.

That in itself is a testament to how his career refused to stay long in any given lane, even after he dialled down the fusion following a conversation with, of all people, Motörhead’s Lemmy.

“He said, ‘Jeff Beck – best guitarist in the world. He goes diddly-iddly-iddly and everybody gets bored,’” laughed Beck, telling the story to David Sinclair. “He was probably speaking for a lot of people. You can’t out-gas yourself to the point where all people can do is sit there with their jaws open. You’ve got to deliver something they can grasp and enjoy.”

Unlike the era in which he made his name, Jeff Beck’s latter decades made little history but supplied a remarkable wealth of great music. For example: Who Else!, You Had It Coming and Jeff, made under the influence of The Prodigy and other dance music disruptors between 1999 and 2003.

“Jeff’s ability to keep on developing and improving as a guitar player decade after decade had a lot to do not only with his musical energy and curiosity but his humility,” says Robert Plant and Radiohead drummer Clive Deamer, who came aboard for Crazy Legs, Beck’s 1993 tribute to Gene Vincent And His Blue Caps. “He was always self-effacing and very doubtful of his own abilities. Before going on-stage he would sound no different to an unconfident 18-year-old – ‘I don’t know if I’ve rehearsed enough…’ – and then he’d set the place on fire.”

Another way Beck bucked a trend among his contemporaries is in the welcome he extended, from the ’90s on, to female collaborators. Not only are the singers to whom he gravitated after locking horns with alpha dogs in his earlier years almost all women – Imelda May, Imogen Heap, Beth Hart, Olivia Safe, Joss Stone and Rosie Bones – but female instrumentalists abound, too, including guitarists Jennifer Batten and Carmen Vandenberg, bassists Rhonda Smith and Tal Wilkenfeld, and drummer Anika Nilles.

“I felt so comfortable around him,” says cellist Vanessa Freebairn-Smith, who worked with him from 2006 to 2018. “I never felt imposed upon or any creepy vibe, none of that chauvinist energy; women who work in music, we’ve experienced the gamut – I speak from experience. He was very gentle and safe and welcoming.”

Jeff Beck performing at a Crystal Palace Garden Party event

“Jeff’s playing and sound were like a voice, very human, a loving, caressing sound.”

Jan Hammer

It’s a sentiment echoed by Rosie Bones, whose year with Beck is an extraordinary tale: having seen her band Bones play at a pub, Beck immediately invited them to collaborate on an album (2016’s satirically charged, politically angry Loud Hailer) and join him on the road.

“We went back and forth to his house in the countryside and hung out by the log fire with bottles of prosecco and bowls of nuts, writing the record on the floor giggling with all the dogs running about,” Rosie recalls. “Jeff wasn’t a lad. I think he felt much more comfortable with a nurturing, feminine energy around him. He was a sensitive soul. He’d cry. He enjoyed the feminine energy in himself as well. He was silly. He’d pootle around the house in this big fluffy onesie with a pair of rabbit ears that [his wife] Sandra had bought him; it was fantastically weird.

“He had a childlike excitement for collaborating with all sorts of people,” continues Bones, “this playful energy that always wanted to explore new things. He wasn’t a natural leader but led if you needed it. His nature was to support the song or the singer, to decorate what was going on. He just played the most beautiful guitar and that’s what he loved.”

These latter years seem to describe a totally different Beck from the young man who, baffled by his own self-sabotaging volatility, talked of ungovernable childhood temper tantrums and the possibility that being knocked down by a car driven by his headmaster might also have had something to do with it.

The Jeff Beck Group (L-R Rod Stewart, Ron Wood, Mickey Waller and Jeff Beck) pose for a portrait circa 1968

“I never felt that there was trouble or dysfunction behind those eyes,” says bassist Pino Palladino. “It was all about the beauty of music. Nobody has ever touched an electric guitar like Jeff Beck, nobody has had those depths of expression, that inbred genius to play the most tender guitar imaginable. Then he could also be such a thug; this terrifying anger came out with the guitar – but with a really pleasant smile while he was playing. I’ve seen a look on his face almost like he couldn’t believe what had just come out, like, ‘Wow, did you hear that?’”

“He’d go between those two worlds within a piece of music in the blink of an eye,” remembers Clive Deamer. “As soon as that guitar went on him you could see his body language change; his brain and soul and the guitar were meeting in this special place. As a musician, it put you on your game to the utmost degree. You had to let your senses go to the same place to be ready to play with him.”

Unlike Les Paul and his inspirational “tricks”, how Beck achieved his vast palette of sounds was all in the fingers and thumbs as they manipulated the volume and tone controls and, crucial to his style, “the whammy bar and bent strings, all the in-between notes,” says Tal Wilkenfeld. “He wasn’t just playing in half steps; it was microtonal, bending all over the place, very influenced by Indian classical.”

Fellow guitarists were often shocked to discover how seldom he used effects pedals, that his amps came off-the-peg and his default Olympic White Stratocasters were barely modified from the standard production model and would often arrive wrapped in the dog’s blanket.

Indeed, for someone whose barely changing late- ’60s dandy rooster image was so rock’n’roll that it was parodied as Nigel Tufnel in This Is Spinal Tap (a movie throughout which Beck roared with laughter at its VIP preview in 1984), he was very un-rock’n’roll. Vanessa Freebairn-Smith thought it hilarious that he’d unwind after a show with a mimosa, and Harvey Goldsmith recalls that this confirmed vegetarian “hated people drinking too much and never went near drugs; he wanted to be in control. He got his jollies playing great music. ‘How did I do? How do I play better?’”

“He was always searching for something that nobody else had thought of, something brand new and revolutionary like reinventing the wheel,” says Pino Palladino, adding with a fond chuckle that, “Jeff had a mystique about him; he didn’t give it all away. In the dressing room before we went on-stage he would usually have an amplifier and be warming up. One time he played something incredible and I said, ‘Wow, Jeff, what was that you just played?’ He turned away from me so I couldn’t see what he was doing with his guitar and said, ‘Don’t worry, mate – plenty more where that came from…’”

This article first appeared in issue 353 of Mojo

Images: Getty