Mojo

FEATURE

Let It Roll

More tape, more musicians, more reverb: George Harrison‘s All Things Must Pass eschewed the simplicities of Krishna Consciousness to become the biggest, possibly best, Beatle solo album of all. Fifty years on, ‘Beatle Jeff”s collaborators remember the whole magical mess, Phil Spector’s shooter and all. “When you’re in the presence of a Beatle,” they tell Tom Doyle, “you never get over it.”

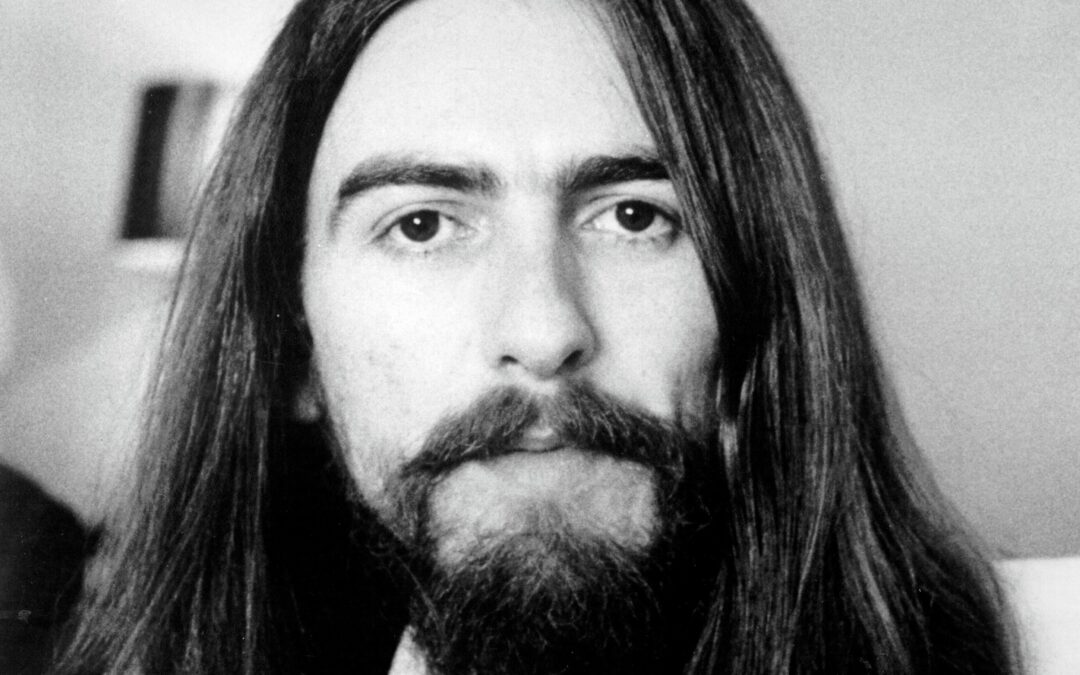

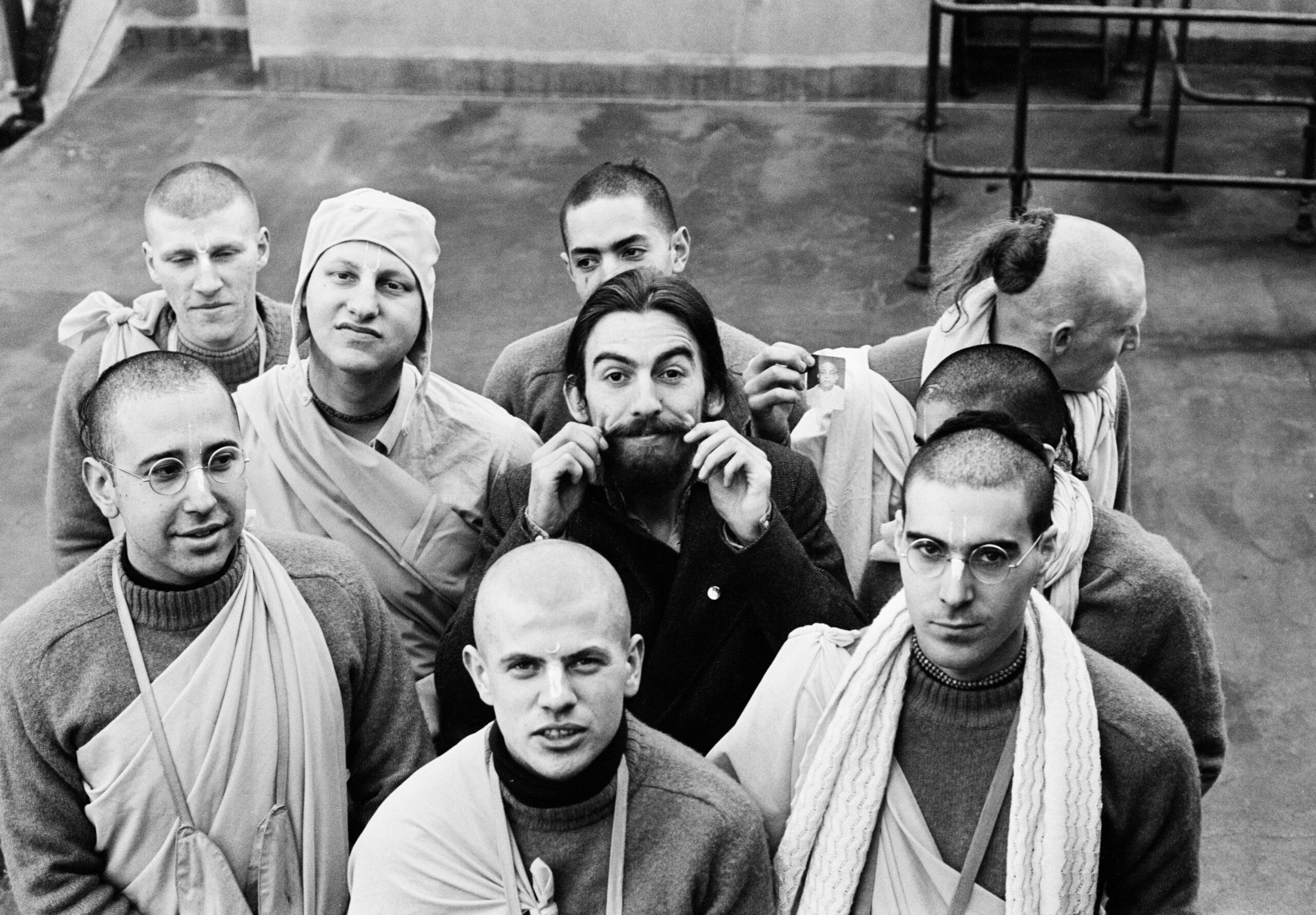

All Things Moustache: Harrison with members of Radha Krishna Temple on the roof of the Apple building, Savile Row, London, 1970.

“Are you ready? Phil?” May 27, 1970, Abbey Road Studios. George Harrison stood alone, facing a microphone, and songs began to pour out of him. On the other side of the glass sat Phil Spector, ‘fresh’ from the controversial overdub and remix salvage sessions for Let It Be, released 19 days earlier. Accompanying himself on either acoustic or electric guitar, Harrison performed 15 sparse demos of only a portion of the songs he’d been stockpiling over the past months and years.

“Phil, this is the one [called] Window Window, and it’s a bit silly,” he announced to the producer, before strumming through a lightly surreal, Dylanesque folk song related to his recent withdrawal from the public eye: “I go for a walk in the shed/And check out the paint and the lead.”

Sounding a touch smoker-croaky, sometimes coughing or offering the odd burp, The Quiet One ran through the compositions he was considering for inclusion on his first solo record. Many – including the gently rousing Mother Divine and the swinging, Revolution-ish Cosmic Empire – wouldn’t make the final cut.

Nearly 25 years later, in 1994, these tapes were bootlegged as Beware Of ABKCO!, its title lifted from a subsequently scored-out line on the original lyric sheet of Beware Of Darkness, a brooding song warning of malign influences and intrusive, negative thoughts. Notably, it took a pop at the company name of Allen Klein. It had been just over a year since three of The Beatles – famously not Paul – had signed to ABKCO. Clearly, Harrison was already having his doubts about the squat, stogie-sucking American.

Some of Harrison’s other unreleased declarations offered insights into his state of mind as he began recording what would become a triple album: All Things Must Pass. In Nowhere To Go, casually coauthored with Bob Dylan two years earlier, Harrison gently railed against police harassment of rock star potheads, confessed to feelings of general rootlessness and admitted his disenchantment with Fabdom.

“I get tired of being Beatle Jeff,” he sang in a weary croon, “talking to the deaf.” In truth, George wasn’t entirely sure if he was still a Beatle or not.

“Most of the time we were running around looking for headphones. It was like, ‘Oh no, more people.”

John Leckie

SIX WEEKS EARLIER, ON APRIL 10, 1970, the day that the front page of the Daily Mirror blared the dramatic headline “Paul Quits The Beatles”, Harrison had characteristically closed himself off from the brouhaha. Inside the walls of Apple at 3 Savile Row, he watched an early rough cut of The Long And Winding Road, the Beatles documentar y that, decades later, was to provide the blueprint for the Anthology series. Responding to the breaking news, an unnamed friend told a reporter, “George doesn’t want to think about it.”

May 1 found Harrison in New York, talking to Howard Smith, a DJ for the city’s WABCFM. In the interview, he openly tried to offer a compromise to his bandmates that might point to a future for the group. “The least we could do is sacrifice three months of the year… just to do an album or two,” he reasoned. “I think it’s very selfish if The Beatles don’t record together.”

At the same time, he talked up the imminent recording of his solo album, clearly viewing it as an extracurricular activity rather than the beginning of a new era. “I’m sure that after we’ve all completed an album,” he said, “or even two albums each, then that novelty will have worn off.” Already he was envisaging All Things Must Pass as a grand design, filled with “trumpets” and “orchestras”. “It’ll be a production album,” he asserted.

It was a time of reflection, uncertainty and creative liberation for Harrison. In December ’69 he had spontaneously joined forces with raucous country/blues/ R&B troupe Delaney & Bonnie And Friends, playing guitar on their short UK tour alongside Eric Clapton. For Harrison, it had been a joyful six days back on the road, even if he’d tended to keep his head down on a shadowy part of the stage.

Then, there was his blossoming friendship and songwriting dalliances with Bob Dylan. In New York in late April ’70, the two had home-recorded a scrappy version of their fresh co-write, the soon-to-be floaty and spectral I’d Have You Anytime. On the same day as the WABC-FM interview in May, Harrison had contributed slide guitar to Dylan’s If Not For You during the sessions for New Morning (a version that ship went unreleased until 1991 and The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3).

Klaus Voormann, bassist, Revolver cover artist and friend of Harrison’s since The Beatles’ Hamburg days, remembers that Quiet George was at the time in fact the most sociable Beatle. “Dylan and George were really close friends,” he tells MOJO today. “George was very much in contact with him. Paul wouldn’t do that and John was sticking to his and Yoko’s side. But George was the guy who was always communicating with people.”

Voormann was a key bass-playing contributor to another important part of the realisation of All Things Must Pass – the January 1970 recording of Lennon’s Instant Karma! single with the Plastic Ono Band and Phil Spector. It was when Harrison arrived to add guitar and piano to the thumping, anthemic single, that Spector first suggested he start to consider his own solo record.

Not that the strange figure in the control room was recognisable to everyone present. “I didn’t know who this little man was with the high voice,” laughs Voormann now. “He gave little messages out in the studio: ‘Can you take the cymbals off?’ I was like, ‘Who is that guy?’ Then he came in the studio and I saw he had ‘P.S.’ in red on his cufflinks.”

Any confusion as to the producer’s identity was blown away the moment the first mix of Instant Karma! was played back.

“We all went in the control room,” recalls Voormann. “The whole place was filled up with tape machines that he used for his tape echoes. And he turned the knob full up, full volume. He played the song and it just hit us. It was just so amazing. It was such a crisp, fantastic sound. It was very, very impressive. And then I thought, Well, that must be Phil Spector.”

THOSE WHO JOINED THE SUBSEQUENT SESSIONS for All Things Must Pass remember Phil Spector showing reverential respect for Harrison. Future record producer John Leckie (XTC, The Stone Roses, Radiohead) was at the time a 20-year-old tape operator only three months into the job at Abbey Road. “Spector was in awe of The Beatles,” he says, “and, of course, they were in awe of him. So, it was strange.”

Peter Frampton, brought in as a session guitarist, agrees. “George was a very confident person,” he says. “Very low-key but very confident. He knew what he wanted. I believe that Phil Spector was not the Phil Spector that he was on the Ronettes sessions as he was looking through the glass at George Harrison. It doesn’t matter how famous or successful you are, when you’re in the presence of a Beatle, especially if you’ve grown up in that era, you never get over it.”

On day one of the sessions, Spector started small, laying the foundations to his Wall of Sound using a band comprising Harrison on guitar and vocals, Voormann on bass and Ringo Starr on drums. Rough tracks cut that day included My Sweet Lord, with a faster, shuffling groove than the version eventually released, and a barebones, electric rocking version of the gospelly Awaiting On You All.

Day two, May 28, was where the fun and games began, as a long procession of musicians entered Abbey Road Studio Three at the invitation of Harrison: Eric Clapton, various members of Delaney & Bonnie And Friends, Billy Preston, Gary Brooker of Procol Harum, drummer Alan White, and more, and yet more…

“Most of the time we were running around looking for headphones,” laughs John Leckie. “There were 12, 15 musicians all playing at once and there were never enough pairs of headphones working. Badfinger [Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland] just sat with acoustic guitars around one microphone. Jim Price [trumpet] and Bobby Keys [sax] came in and said, ‘Where should we stand? Where can we fit in?’ And it was like, Oh no, more people.”

The first track laid down was My Sweet Lord, transformed from the previous day’s scratch version into a heavenly mass-strummed mantra. Again, Spector worked his magic in the control room. “It was nothing like what we’d just played out in the studio,” remembers Gary Brooker. “Because suddenly Phil Spector had swamped it [in reverb]. The Wall of Sound.” Given the mass of players and loose, revolving door approach to who might be involved on any one take, it later became difficult for anyone to accurately remember who’d played what. The credits record that Ringo and Delaney & Bonnie’s Jim Gordon both played drums on My Sweet Lord. Alan White swears it was him alone.

“George said to me, ‘I want you to play the drums,’” White remembers, “and I said, ‘Well Ringo’s here.’ He said, ‘No, I want you to play the drums and Ringo can play tambourine.’ It didn’t make me feel comfortable at first.”

“We probably finished My Sweet Lord at about two o’clock in the morning,” Leckie recalls, “and they went straight in and did Wah-Wah, which is pretty live.”

In terms of studio atmosphere, Spector had certain requirements: low lighting everywhere; the speakers in the control room set to maximum volume; the air con blasting out in the live room. “Oh yeah, it was freezing in there,” White confirms. “He thought people played better when it was cold.”

John Leckie remembers Phil Spector being a very active conductor of the musical proceedings: “He’d go, ‘Stop stop stop. Eric, what’s that G chord you’re playing? I told you to play an F.’ He was very much into musical direction.”

As the sessions continued into June, Clapton’s role in the tracks grew, his fluid and soulful lead guitar contributions to opener I’d Have You Anytime only the most striking. Voormann recalls that Harrison and Clapton’s creative relationship was one of mutual appreciation. “George could never play a free solo,” he says. “It was very, very difficult because his guitar playing was very limited, and he knew that. He always said, ‘I wish I could play like Eric.’ In comparison to that, Eric was saying, ‘I can’t play like George. George creates these great rhythms and melodies and I play differently.’”

The recordings flowed, but one track was problematic. Dating back to 1966 (some say it was in the running for Revolver; others Sgt. Pepper…), Isn’t It A Pity was a lament for destructive human relationships, all the more poignant amid The Beatles’ disintegration. A slow-build seven-minute version was recorded on June 2. The next day, 20 takes of a sparser, more downtempo rendering were committed to tape. Ultimately, Harrison chose to include both on All Things Must Pass.

As the band grew in size on certain tracks – the enormous, propulsive What Is Life, the now-densely energised spiritual anthem Awaiting On You All – sporadic moves next door to Studio Two were required, with the musicians positioned in rows like an orchestra. “Sometimes the guitarists were sitting opposite each other with no baffles,” says Voormann. “Acoustic guitars in the same room playing when we were doing drums and electric guitars.”

Not that Spector’s only talent was for towering layers of sonics. Voormann says the producer could work more subtly, as on Behind That Locked Door, Harrison’s song of gentle encouragement to his reclusive friend Dylan. “If it was a song that was more country-like, not this Wall of Sound thing,” says the bassist, “Spector was very delicate. Whatever was needed for the song he would do. Everybody thinks, Oh he was a bully and he was forcing certain stuff on [the musicians]. He never did that. He was listening very closely to the songs.”

“Eric was saying, ‘I can’t play like George. George creates these great rhythms & melodies.’”

Klaus Voormann

HAVING RENOUNCED DRUGS IN FAVOUR OF spirituality since 1968, George Harrison remained clean during the recording of All Things Must Pass. “George would often sit at the back of the control room during the playback,” John Leckie recalls. “You could hear him whispering in the corner, ‘Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna.’ He had a little beanbag round his neck where he’d count his mala beads.”

In sharp contrast, most of the other musicians indulged in alcohol and weed (and furtive harder drug-taking). “Everyone else, of course, was completely out of it,” Leckie laughs. “At the end of the sessions, we used to go round the ashtrays and nick all the spliffs, because a lot of them weren’t smoked. They’d roll a joint, have one puff and put it in the ashtray. So, the ashtrays were full of unsmoked straight grass American joints. Also, I had a bottle of Eric Clapton’s tequila which I took home and put on the mantlepiece. My mates would come round and say, ‘Oh, shall we have some of Eric Clapton’s tequila?’”

The freestyle recordings that were to make up the third, Apple Jam disc on All Things Must Pass were typically recorded in-between official takes, when the musicians slipped into extended noodling. For John Leckie and engineer Phil McDonald, this usually prompted an hour-long escape to the Heroes Of Alma pub around the back of Abbey Road.

“I’d put a tape on the stereo machine, put it on 71/2 IPS, which meant it went on for an hour and four minutes,” says Leckie. “Me and Phil McDonald could run round to the pub, have a pint of Guinness and a sandwich and get back before the tape ran out. You’d come back and it would just be spooling off and the band would still be playing.”

Phil Spector’s alcohol consumption was more of an issue, as he began to drink heavily in the studio (“He used to have 18 cherry brandies before he could get himself down to the studio,” Harrison later recalled) and grew dangerously erratic. “One day I went back into the control room and I noticed there was a gun on the console,” Alan White recalls. “You never saw that in England. Phil was a guy who was pretty paranoid. I think he believed somebody was gonna kill him at any time.”

According to Klaus Voormann, the root of the problem was friction between Spector’s high-octane, fast-moving studio methods and Harrison’s slow-burning perfectionism, particularly after the full band recording was done and George moved into overdubbing.

“When George was doing all those overdubs, Phil would’ve been bored to death,” Voormann stresses. “His way of recording was so different. George was very slow and trying it again another time and putting another guitar on it. So, Phil got bored and drank another one (laughs). He was getting outrageous. When George was mixing, Phil was already half-drunk.”

One day, a lathered Spector fell off his studio chair and injured his arm. Not long after, he returned to America. “That was difficult for George,” says Voormann. “Because in a way he wanted Phil to stick with him for the mixing and the finishing of the record. But it sort of dissolved.”

Come August, the project moved from Abbey Road to the state-of-the-art Trident Studios in Soho, where the 8-track tapes were transferred to 16-track to allow for extra layering. The absent Phil Spector sent Harrison a five-page letter from the States detailing his thoughts on the rough mixes, which were mostly concerned with Harrison’s vocals and revealed that, even if in awe of The Beatle, he wasn’t afraid to push him.

Of the title track, Spector wrote, “I’m not sure if the performance is good or not. Even the first mix you did, which had the ‘original’ voice, I’m sure is not the best you can do.” Of Behind That Locked Door, he reckoned, “The voice seems a little down. I think you could spend whatever time you are going to on performances so that they are the best you can do. I really feel that your voice has got to be heard throughout the album so that the greatness of the songs can really come through.”

“Sometimes we’d listen to them, sometimes we’d ignore them,” says producer Ken Scott (David Bowie, Devo), then an engineer at Trident, of Spector’s notes. “George’s big thing was backing vocals. On My Sweet Lord, all of the backing vocals were him. There are some, the really high ones, where we slowed the tape down so he could do it, then came back to normal speed. You hear them on their own and it’s hysterical. It’s Mickey Mouse. He was confident, but we still did take after take.”

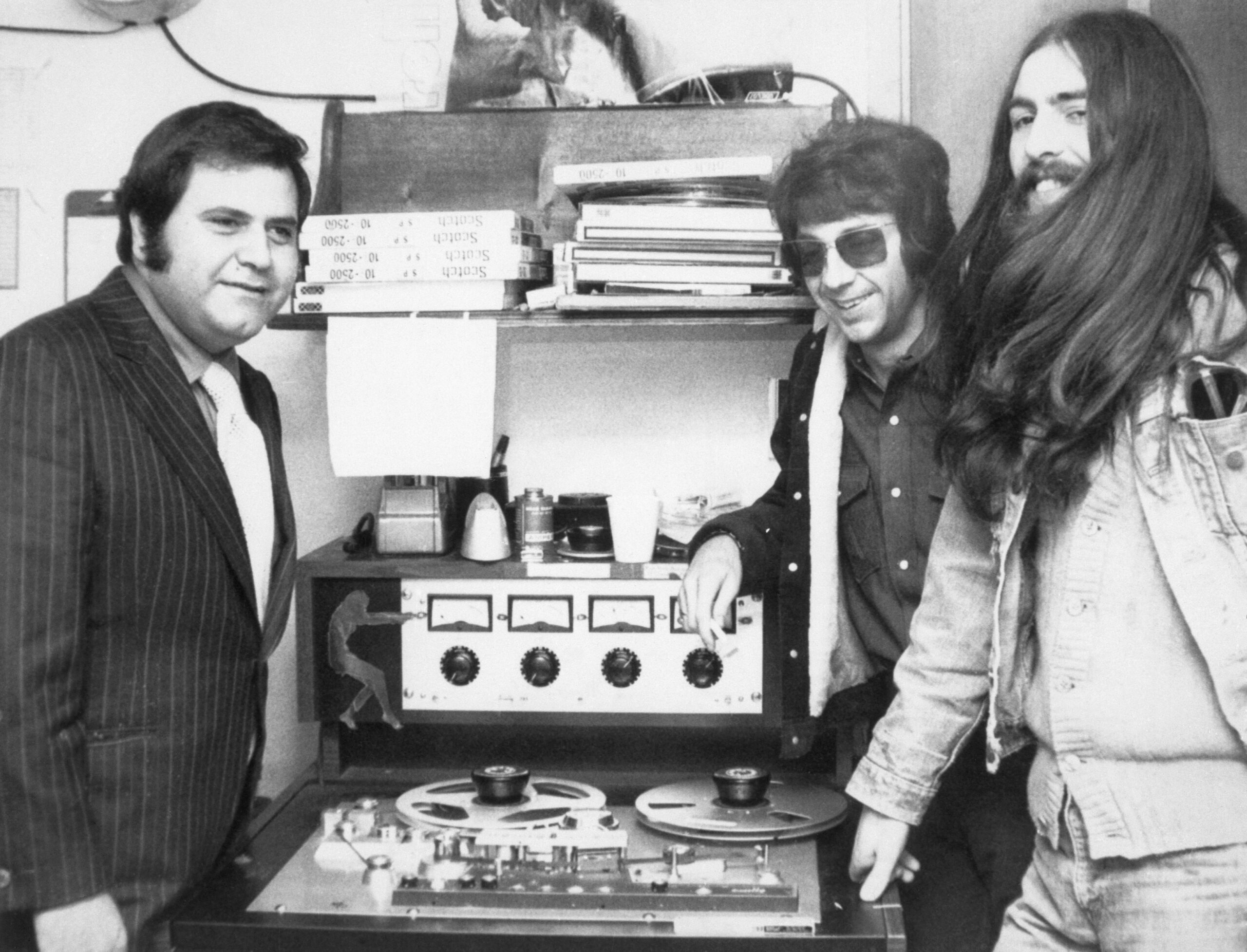

Phil yer boots: Pete Bennett, Phil Spector and George Harrison listen to the masters of ATMP.

“There was a gun on the console. I think Phil believed somebody was gonna kill him.”

Alan White

ODDLY, THE FIRST TIME THE RECORD-BUYING public heard any of the new George Harrison material was with the September 1970 release of Billy Preston’s second Apple album, Encouraging Words, which featured a version of My Sweet Lord ramping up its gospel aspects and another of All Things Must Pass revealing the soul song partially hidden within.

The triple-vinyl All Things Must Pass was issued in November, housed in the type of hinged box previously used for classical or opera records. Its heft and higher retail price didn’t stop the album becoming a transatlantic Number 1, buoyed by wall-to-wall airplay for My Sweet Lord. Klaus Voormann remembers first seeing the finished product stacked up in Tower Records in Los Angeles.

“George’s heap of records was going up to the ceiling,” he laughs. Critical response was similarly vertiginous. Ben Gerson in Rolling Stone described the album as an “extravaganza of piety and sacrifice and joy, whose sheer magnitude and ambition may dub it the War And Peace of rock’n’roll”. But Harrison’s fellow ex-Beatles (represented on his album cover – as its photographer, Barry Feinstein, would later contend – by four garden gnomes) were less free with their praise. McCartney kept his counsel. Lennon, interviewed by Jann Wenner in December 1970, said, “I think it’s better than Paul’s” – faint praise, since he’d described McCartney as “rubbish”. Ten years later, he had softened a little, telling Playboy that All Things Must Pass was “all right” before judging that Harrison had “walked right into” the then-notorious, long-running plagiarism case against My Sweet Lord. By then, Harrison had already paid out over $1.5m to the owners of The Chiffons’ 1963 hit He’s So Fine, and would not be fully rid of the action – taken up by his old bugbear, Allen Klein, who’d purchased He’s So Fine’s publisher, Bright Tunes – until March 1998.

Over time, another aspect of All Things Must Pass would trouble Harrison: namely, Spector’s production. Revisiting the tapes in 2000 (for the anniversary edition actually released in 2001), he and Ken Scott sat side-by-side in front of the mixing desk at his home studio in Friar Park, Henley-on-Thames, and pressed ‘play’. “At one point, we just looked at each other and burst out laughing,” Scott remembers. “It was twofold. One, here we were 30 years on, sitting there listening to exactly the same tapes in exactly the same positions. And then the other thing was all of the reverb. We’d both sort of moved away from wanting to hear it. So, we were both laughing at that. We would both have loved to have gone in and just ‘de-Spectorised’ it all.”

It was to prove impossible, however; many of the Spector effects had been imprinted onto the tapes, mixed in with the parts. In the linernotes for the 2001 reissue, Harrison admitted, “It was difficult to resist remixing every track. All these years later I would like to liberate some of the songs from the big production that seemed appropriate at the time, but now seem a bit over the top…”

For their 2000 remix of My Sweet Lord, Harrison and Scott ended up ditching many of the original performances, adding a new lead vocal, backing vocals by Sam Brown (daughter of Harrison’s pal Joe) and acoustic guitar played by George’s son Dhani Harrison. “I think it was just a question of… if we were going to go for it, we had to go for it all the way,” says Scott.

Half a century on, despite its creators’ reservations, All Things Must Pass is what it always was: a masterpiece – for many, the greatest Beatle solo album. None the worse for its length or the extent of its cast list, it’s a deluge of songwriting creativity transfigured by a squadron of musicians whose excitement is palpable in every groove.

For Klaus Voormann, playing it now prompts a rush of welcome memories. “When I listen to it today, it’s such a good feeling,” he says. “You see, I stayed for a long time in the studio, even when the recording was finished and I had played my part. I was sitting there on the sofa through the whole session ’til the last minute. I loved being around the songs and the music that was happening.”

These days, Ken Scott often gives talks for audiences on his production career, isolating key elements from multi-tracks to that people are still listening to All Things Must Pass 50 years on mind-boggling, but reveals that Harrison’s vocal track on What Is Life, freed from its instrumental baggage, sends shivers through every group of listeners he plays it to. And so, in the end, this most maximalist of rock albums is pared back to its roots, to its soul.

“Listening to George’s vocal on its own,” Scott concludes, “you hear just how good he was.”

This article first appeared in issue 319 of MOJO.

Images: Getty