Mojo

INTERVIEW

Lemmy

Speed kills… but not when you have the constitution of a warthog and you’re the Lewis gun of the bass guitar. Cue tales of Sid Vicious, Hendrix and… The Nolans from Motörhead legend Lemmy in this archive interview from 2011

Motörhead frontman Ian Fraser Kilmister (aka Lemmy), November 2010.

THERE’S AN OZZY BILLBOARD ON THE roof of the Rainbow Bar & Grill, the famed rock star hang-out on Sunset Strip, Los Angeles. But on the ground, right at the entrance door, there’s a Motörhead flagstone – a black marble square set in the concrete like a one-man Rainbow Walk Of Fame. A fan in the UK made it for him and when Lemmy moved to Los Angeles – his apartment is a short walk down a hill whose gradient poses a challenge to stiletto-wearing women – he brought it with him. He’s hoping, he says, that they’ll dig it up and set it into a wall. Which is understandable. Lemmy’s reason for quitting England for the States was that he was sick to death of being trodden on.

But at the Rainbow, Lemmy is the Godfather. The girls all make a fuss of him. The musicians do too. And when the Hummers and SUVs threaten to drown his low, husky voice when we start the interview at an outdoor table, he gets special dispensation to smoke inside – and this in a city where murdering your wife is more socially acceptable than smoking a cigarette.

Dressed head to toe in black – black hat (cowboy), black boots (biker), black jacket (some mix of the two), long black hair – he sinks into the black walls of a back room where the afternoon sun won’t penetrate. Over the next three hours, while getting through three Jack Daniel’s and Cokes, several more Marlboros and racking up an impressive score on a video game machine, he proves that the old adage Speed Kills is not entirely true. “Or if it does,” he grunts, “it takes fucking ages about it. I’m still around. Fuck ’em if they can’t take the pace.”

The Ace Of Spades: Lemmy and Motörhead perform at Glastonbury 2015

What made you leave Britain for America?

If we’d stayed in England, we would have been finished within a year, because we had nothing. It was deadly. On a personal level I was doing all right, I was still getting plenty of birds and that, but on every other level – we were getting no gigs, the albums weren’t selling at all, and I moved over here and it gave us a new lease of life. We wouldn’t have gotten a Grammy if I’d still been living back in England.

You chose to live in LA, the epicentre of youth and beauty culture.

And I’m not shot full of botox. Long hair hides a multitude of sins. I never believe these people who, as they get older and uglier, cut their hair shorter. Why expose more of the terrible ravages? I had my teeth done – just like Keith Richards. I had to. They were falling out. Good job too I must say. LA is the place for teeth.

Your first musical love was an American. You must have been 11 or 12 when you heard Little Richard…

Yeah, on Radio Luxembourg, the only station then playing rock’n’roll in Britain. It used to cut out all the time, so you’d hear a record you really liked and then it would go skkkssssssssh so you wouldn’t know who did it and you couldn’t get it and you’d have to wait for four days with your ear glued to the radio until they played it again. I used to sit like that the whole evening listening to the radio, and Little Richard for me was always the best of them: that fierce joy.

Not much of that in your life then, as the only English kid in a Welsh school?

I rest my case. I moved to Wales when I was about seven or eight and came out when I was 18. I know what it’s like to be a minority, believe me. One in 700. A couple more arrived later, but at first it was only me, and in primary school it was only me.

You were bullied?

They actually lined up to fight me. One at a time. That’s where I learned how to fight, and also learned how pointless it was. No matter how many you beat there’s always another one. Another 200 actually.

When did playing music come into the picture?

My mum had a guitar hanging on the wall – a Hawaiian steel, shaped like a Spanish guitar but the strings were high up and you played it flat on your lap. I played it like a regular guitar. It gave you strong fingers. Death grip. That’s how I got to play the bass so fluently. I used to take it with me to school to impress the chicks and it worked like a charm.

What were your earliest bands like?

There was a bunch of them – The Sundowners, who were truly awful, The Blue Jays which was psychedelic, The Motown Sect – we just called it that to get gigs. Cover bands – Shadows stuff mostly; I can still do the steps. But I was playing rhythm then, and the bottom fell out of the rhythm market, so I had to try and become a lead guitarist and I’m no good at lead. I’m good at rhythm. Good at driving a song. The first one to make records was The Rockin’ Vickers.

A fitting band for a vicar’s son.

My father left when I was three months old. The Reverend Sidney Kilmister was a Protestant vicar and the biggest hypocrite. How can religion not piss you off? My mother, in order to get remarried to my stepfather, George, who used to play for Bolton Wanderers and who was a Catholic, had to write to the Pope to ask his permission.

How was life in the Vickers?

Lots of revolving stages – Blackpool, Manchester, Burnley. South of Birmingham we were unknown, but north of Birmingham we were getting £200 a night, which is about two grand now. We all had cars. Ciggy [Shaw, drummer/leader] had a speedboat, we used to go skiing on Windermere. We had this tax guy come around once. Me and Moggsy [bass] were out on the front lawn, sunbathing, with two birds on a towel, and the speedboat’s there and two Jaguars and a Zephyr 6. He comes in the house – in Cheetham Hill, Manchester, respectable area – and Harry [Feeney, vocalist] is reclining on the couch with this chick doing his toenails. The guy says, “I’m from the Inland Revenue.” Harry says, “It’s too late man, we’ve spent it.”

The Vickers covered, more accurately nicked, The Who’s The Kids Are Alright [released as It’s All Right]…

They were playing it before I joined the band, pinched it, added half and [Pete] Townshend threatened to sue. The Who became good mates later; we played with them in ’65, supporting them at the South Pier in Blackpool. We had a farm back then and Moonie used to come over. Our manager was the local promoter, so everyone used to come round for a knees-up after the shows: Lulu, who was a fucking raver back then, The Tremeloes, who were nutters, real party animals. I remember The Tremeloes dumping Lulu into the water trough at four in the morning. But Moonie had the edge on everybody. He had a milk float and a hovercraft and all these vehicles, and he used to chase the pony in this hovercraft. One day it just lay down and wouldn’t move. He got the vet over, who said, “It’s got clinical depression. It’s having the pony equivalent of a nervous breakdown.”

“Hawkwind were the most cosmic band, supposedly, and I got sacked for getting busted.”

Lemmy

It was a Who roadie who got you the gig roadying for Jimi Hendrix…

Neville Chesters, a good guy. He was living with Noel Redding and I was crashing on his floor. And that’s how I got the job, because they needed another geezer and here was one sleeping on the deck.

Did Hendrix pay well?

Ten pound a week, which was pretty good then, and the side benefits were great. Chicks mostly. Oh man. You’ve never seen anything like it, even The Beatles. Chicks were just drooling all over him. Because of the way he moved – he was like a cat crossed with a spider, and he’d just fascinate people. It would be like a rabbit with a snake, he’d just pounce. And he was really well-mannered too – pull chairs out for chicks and open the door, which I still do now, because I was taught that way by my ma. I was relieved to find that someone who looked like him would still do that. And on that tour I saw all these great bands for free – The Move, Pink Floyd with Syd Barrett, Amen Corner, The Nice. And Hendrix, of course, who just stunned me. He stunned everybody. Clapton used to come to the shows and he would stand there like a kid, mouth open, goggling.

Did Hendrix introduce you to acid?

’Fraid so. Before that I was a dope smoker like everyone else – everyone I knew anyway. Neville said, “Do you want to try some acid?” They had just come back from America and Stanley Owsley had given them like a hundred thousand tabs; it wasn’t even illegal then. He gave me this pill so I took it, then turned around just as he was getting a knife to cut it up into four. It was a big overdose – about two thousand mikes and the average dose was 365 – so Neville took a whole one as well, which was very cool, and came with me. Eighteen hours. I was sitting under a Hendrix poster on the wall, the one where he’s dressed as a Red Indian, and I was behind him, in that swamp, with the alligator. Great fun. Then Neville said, “Let’s go to the Speak[easy],” so we went and there was The Nice playing, the first light show I’d ever seen, and Keith [Emerson]’s throwing knives into his keyboard. It was some evening.

Did acid inspire any songs you wrote?

When I was in Hawkwind it did. I didn’t write a lot of songs with Hawkwind, but I wrote The Watcher, which was definitely an acid song, and I wrote Motörhead, which wasn’t. I quit [LSD] in ’75.

It was messing with the speed?

Liquid meth it was then. Lethal. That’s where “Speed Kills” comes from, but I was, like, 20, so what the fuck? That’s how I wrote all the songs on that Sam Gopal album in one night.

You joined Hawkwind in 1971 and sang on their only hit single, Silver Machine…

And pissed them off too, because I’d just joined the band and there it was at Number 1. I don’t remember much about it, because we were all tripping at the time, but everybody else tried singing it first and none of them could reach the high notes.

In Hawkwind you switched from guitar to bass.

I owe Hawkwind that, because I’d never have thought of playing bass and I would have just been a mediocre guitarist still. They needed someone who could play bass, because they were playing a free festival and their bass player [Dave Anderson] wouldn’t do non-paying shows. Dave [Brock] points at me and goes, “He does.” And the guy left his bass there, the stupid arsehole, like “Please take my job”. So I did.

Why did it turn sour with Hawkwind?

It was great at the beginning, though I never really got along with Nik [Turner], he was always quite snotty. There was a real hierarchy in the drug-taking fraternity in those days. Speed was a Very Bad Drug, and people who did acid weren’t really taking drugs, they were broadening their mind, improving themselves and all that malarkey. And I was a speed freak. Then I got busted going into Canada, and even though they dismissed the charges that put the lid on it.

How did you feel about being fired? Angry? Vengeful?

Yeah. I went home and screwed two of their old ladies. Mind you, it’s not as good as it sounds because I was already doing one of them before I left. They just pissed me off. I mean, Hawkwind were the most cosmic fucking band in the universe, supposedly, and I got fired for getting busted.

Silver Machine: Hawkwind c. 1973, (L-R) Nik Turner, Dik Mik, Del Dettmar, Simon King, Dave Brock, Lemmy.

Was your original motivation for Motörhead to be a better Hawkwind, and beat them at their own game?

I wanted to be The MC5 really. Really I wanted to be the MC5 all along, only back then I didn’t know The MC5. That’s what I wanted to do though, a five-piece, kick ass rock’n’roll band.

Though you came out at the same time as punk, you were considered a bikers’ band.

I was living with two of the Hell’s Angels when we started. They used to come to the shows because they were mates of ours. No one else did; we played a lot of shows to four guys and his dog.

The first Motörhead album actually released was on Chiswick. So you were labelmates with The Damned.

We were going to break up because we weren’t having any success, and we had a gig at the Marquee and I asked Ted Carroll, the owner of Chiswick, to come down and bring a mobile [studio] so we could leave something for posterity. He said he couldn’t but he would help us make a single and gave us two days, one for each side. On the first night we did 11 tracks. Then we all waited for Jeff Beck to show up because he was co-owner of the studio. He didn’t. But we did cross over with punk, I suppose. Sid Vicious used to kip on our couch with Viv [Albertine] out of The Slits. We had a big squat in Holland Park, a house that was owned by Barbara Hulanicki, the woman who had Biba’s. I tried to teach him to play bass, but I couldn’t do it – he was not terribly bright – then about three months later he’s in the Pistols, stillnot playing the bass. But Sid never had a fucking chance. As soon as Nancy [Spungen] got hold of him he was dead meat. That was it for him.

What was she like?

A pig. I could never understand it, because he was devoted to her. I still can’t make up my mind if he killed her or not. He was capable of it, violent enough when he got going. I’ve seen him beat up a Speakeasy bouncer and you know how big those fuckers were, and him just a bundle of fucking pipe-cleaners. I remember coming out of the Speakeasy one night, Sid behind me, and Whispering Bob Harris was at the bar. Sid says, “Hang on a minute, you’re that cunt from the Old Grey Whistle Test aren’t you?” Bob said, “Yes.” And Sid went whapp! and knocked him over.

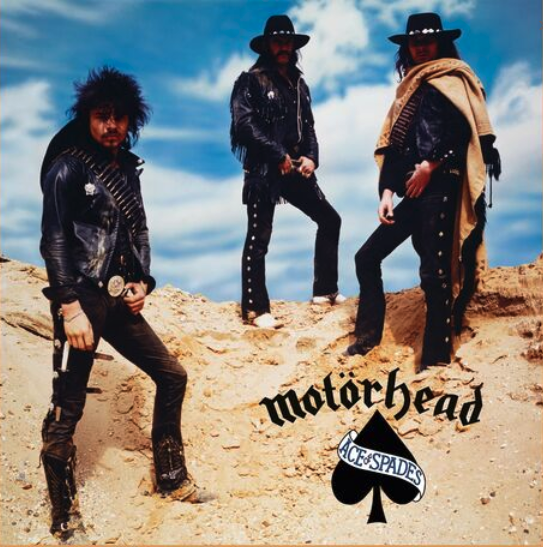

1980’s Ace Of Spades

Leaping forward, to Ace Of Spades. What was the inspiration and did it feel like you were making a classic?

We were on a roll. Overkill and Bomber were in the charts, so we knew it would do all right. The song Ace Of Spades was about the one-armed bandits me and Slim Jim [Phantom, from The Stray Cats] used to play down the Embassy club in London – so it was all the gambling clichés I could think of. The cowboy thing on the sleeve was [drummer] Phil [Taylor]’s idea I think – shot in a sand quarry in the north London suburbs.

You sound as if Ace Of Spades were a millstone as much as a classic.

I just got sick of people going, “Ace Of Spades, dude!” as if that was it and we sucked after that. “You guys still bringing albums out?” That really pisses me off. Because if you like a band, you listen to their new stuff too, surely. And then came No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith, which was our claim to fame, straight in at Number 1 – and then that moment has to define you, see. That’s the trouble.

Are you always “Lemmy” the character, or do you turn into someone else when you get home?

You know that’s not true. If you live on your own, like I do, and there’s no audience, of course it’s kind of quiet. But I know how to make an entrance and an exit very well.

Does anybody call you Ian any more?

My mum and my stepsister Pat.

Let’s talk about women. In the past you’ve duetted with Girlschool, The Nolans, Wendy O Williams…

All these heavy rock guys think, If it’s got tits it’s no good, but that’s not true. Kelly Johnson of Girlschool, people used to say, “Good guitarist for a girl,” and I’d say, “Fuck you, she’s better than you,” because she was a magic guitar player. If you listen to the solo on Don’t Call It Love or The Hunter, she plays like Jeff Beck with The Yardbirds. And now she won’t even touch the guitar because she’s so disillusioned. The Nolans are more of a cabaret act, it was just having fun – and The Nolans are a good laugh, believe me. Those chicks are not shrinking little fucking violets.

Nor, presumably, was Wendy O…

She was actually a very tense person, kind of shy. But strong, She used to throw me around the room. She’d call me up when I was in New York and say, “What are you doing?” Not much. “Can I come over and jump you?” And when she jumped you, you stayed jumped, believe me, because she didn’t take drugs or drink and was a workout freak. Muscles like steel ropes. But she was very innocent really, kind of like a hippy. We lost touch for a bit and I just got her number and was going to call her, and she killed herself.

You’re about to duet with Joan Jett – for what?

A solo album – me singing with a bunch of different people. I did a track with Dave Grohl, and The Damned, Skew Siskin, the singer from Meldrum, and I’m going into the studio again with Slim Jim and Danny Harvey. I met Joan the first time she played England, with The Runaways supporting The Ramones. She wore my bullet belt on-stage. I’m going to do a track with my son Paul – a very good guitar player, better than me. I’m trying to do a track with Jeff Beck, but he’s so fucking hard to pin down – that’s my whole life, waiting for Jeff Beck. And I’m going to do two individual tracks with Phil [Campbell] and Mikkey [Dee].

Those last two being the current Motörhead line-up…

…Which has been the longest-lived and produced some great albums. I think [last album] Inferno is a great album by anyone’s standards and stands up to anything we’ve ever done anywhere.

Most people talk of the Lemmy-Phil Taylor-Eddie Clarke line-up as “classic”.

It was a great line-up but we didn’t think of it as “classic”. None of us remember much about it because it was all rushing around. There’s no animosity. Life’s too short. Phil lives here so I see him all the time. I see Eddie when I go to England.

Is there anything that with the wisdom of time you would change?

Just one thing. I’d finish Iron Fist [1982]. Because we didn’t have it finished – because you were working under the clock as usual – and they put it out while it was still being made – those fucking assholes. And following a live album that’s gone straight in at Number 1 with a substandard, cobbled-together album – still, you can’t live in the past. I can’t live in the past. I don’t want to be an “elder statesman”, where they give you a Grammy and it’s a mercy fuck because we’ve been going for 30 years – and we got it for a Metallica cover too, not even one of our songs. I want to be somebody who’s possibly a contender, who’s got a chance.

Is there a goal you’re still going after?

I’d like to get in the American Top 100 for once – we’ve not done that yet. I’d like to have another Number 1 in England, just to say fuck you. (Lemmy licks his middle finger and thrusts it in the air…)

You were considerate enough not to go in dry.

You’ve got to give them a bit of lubrication, else they can’t get all the way down. I was well brought up.

This article originally appeared in issue 207 of MOJO

Interview: Sylvie Simmons Images: Getty