Mojo

FEATURE

Reintroducing The Band

Twice derailed by egomania, hard drugs, and Britpop, Suede sashay on – wiser, sturdier and, they assert, more creative than ever. An upcoming new album – Antidepressants – revives formative influences (Magazine, The Cult, Crass) and points vigorously to the future. One in the eye for the pundits, and at least one notorious German sceptic? “Stubbornness is in our DNA,” they tell Keith Cameron.

Words: Keith Cameron

The thin black line: Suede practise mood elevation at John Henry’s Rehearsal Studios, London, June 4, 2025, (from left) Mat Osman, Brett Anderson, Richard Oakes, Simon Gilbert, Neil Codling.

On September 14, 1996, Suede’s new album Coming Up went straight to Number 1 in the UK chart. During the four years since debut single The Drowners reinvigorated the British pop lexicon, the band had seen their spectacular initial momentum outrun by brasher rivals and undermined by internal dramas, chiefly the disintegrating partnership between mouthy popinjay singer Brett Anderson and quiet virtuoso guitarist Bernard Butler.

When the latter quit towards the end of fraught sessions for 1994’s epically ambitious second album Dog Man Star, and was replaced by a 17-year-old schoolboy fan, Richard Oakes, Suede were written off by critics and disparaged by hardcore devotees. So for Coming Up to reach the highest peak felt like sweet vindication.

Yet touring Germany a month later, it became very clear that some still refused to accept this new model Suede as worthy of the name. In Hamburg, one audience member greeted Butler-era songs by holding up a sign saying “You are great”. Whenever a Coming Up song was played, he flipped the sign over. It now read: “You are shit”. Things became heated when Brett Anderson attempted to confiscate the sign, and in the ensuing kerfuffle the protestor briefly ended up on-stage.

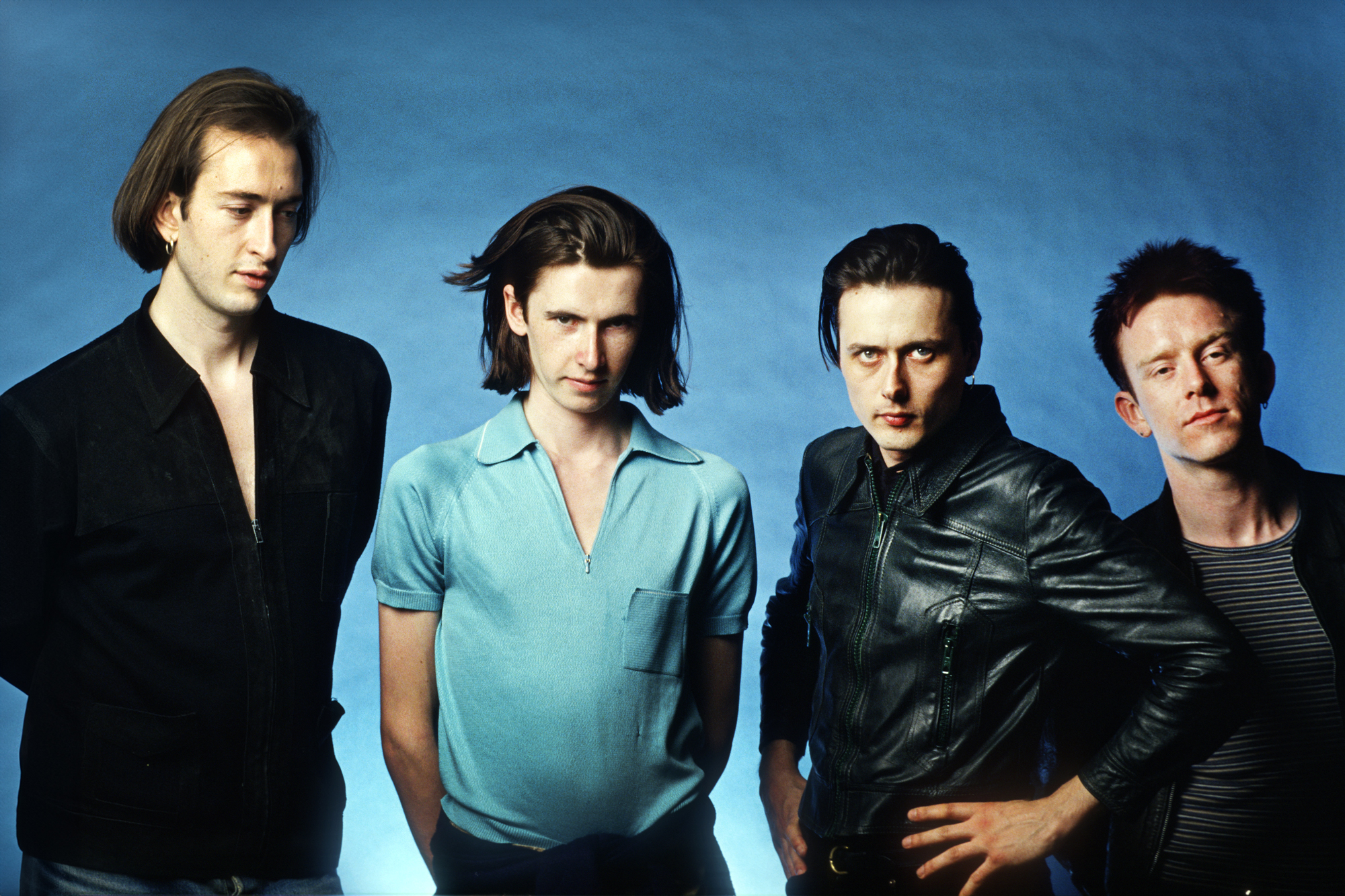

Suede circa 1993’s debut album, (from left) Osman, Bernard Butler, Anderson, Gilbert

“I do remember a couple of gigs in Germany where things like that happened,” frowns Neil Codling, who joined Suede via his cousin, drummer Simon Gilbert, during the Coming Up recording sessions, initially as a keyboardist, with his remit soon encompassing guitar, songwriting and production. “There was another one where someone had a sign saying ‘Coming Up is going down’. We were always a Marmite band, even among our own fans! That hasn’t changed, it’s still this ‘I can’t believe the wrong line-up of Suede has been going for 20 or 30 years…’ The fact that we’re still here, despite being outsiders in whatever sphere you care to look at, must be a motivating factor. Stubbornness is in our DNA, I think.”

Brett Anderson remembers his German nemesis with something like nonchalance. “If I’m not mistaken,” he says, sipping tea in his west London flat, “he was throwing coins at us as well. He was just really pissed off with us for making Coming Up. He probably wanted Dog Man Star II – lots of people did.” Anderson laughs. “Yeah, quite an exciting gig! But I think the best gigs have a little bit of tension. There’s always got to be confrontation. Look at footage of a Sex Pistols gig, it’s like a fucking war zone. Mutual love-ins don’t work. And an audience changes how you respond to your own songs. I listen back to the early stuff we recorded compared to how we play it live now, and it’s toothless. So Young feels like we’re half asleep. The intent with Suede now is always to remind ourselves we’re at our best when we’re energised, and bring that to the studio. I like a bit of grit in the lens.”

The Coming Up-era Suede (from left) Gilbert, Oakes, Anderson, Osman, Codling, August 10, 1996

Grit has come to define Suede. September sees the release of Antidepressants, their tenth album and the fifth since 2010’s reunion, a remarkable creative streak when re-formed groups of their age typically regard making new music as an obligation to boost profile and tour revenues. Yet beneath the Byronic languor of their early public image, there was always a steely edge to the band. It took substantial quantities of grit to tough it out through the dog days of Britpop, the cultural moment that Suede arguably ignited but with which they never felt comfortable. Even after his band graced 19 music magazine front covers prior to releasing its first album, Anderson still felt like he was on the outside of everything: a Crimplene Camus, the latest manifestation of a fatalist romantic persona that coalesced in Haywards Heath, the Sussex commuter town marooned between London and Brighton, where Brett Anderson met future Suede bassist Mat Osman at sixth form college and started a Smiths-smitten bedroom band called Geoff.

Their alliance tightened at the University of London, where these two gauche products of penurious lower-middle-class England met moneyed, confident Justine Frischmann – “one of the two great loves of my life,” Anderson wrote in his 2018 memoir Coal Black Mornings – with whom they began the band that became Suede in 1989, recruiting Bernard Butler via an NME advert: “Guitarist wanted for inexperienced but important band. Influences – Smiths, Lloyd Cole, Bowie, Pet Shop Boys. No musos, no beginners.”

“We were always a Marmite band, even among our own fans! That hasn’t changed.”

Neil Codling

What had seemed wishful thinking then looked remarkably prescient four years later when the self-titled debut album revealed those influences virtually intact. Although de rigueur at the twilight of indie’s defining decade, by 1993 Suede’s kitchen sink bohemian glam of knee tremblers, drugs and milky tea stuck out amid the laddish fag-end of Madchester and grunge’s pained authenticity. Their fluid otherness and media ubiquity – Suede became the fastest-selling UK debut and won the Mercury Prize – made them an easy target, fatally puncturing the group’s fragile equilibrium. With hindsight, Coming Up’s Number 1 was a pyrrhic victory, heralding the long downward spiral to 2003’s dispiriting split in the wake of Anderson’s drug addiction and Neil Codling’s ill-health (he’d left in 2000, suffering from ME).

In this context, reuniting the Coming Up-era line-up in 2010, initially for live work then 2013’s Bloodsports, was no straightforward decision.

“The last year that Suede were together, in terms of the general mood, that really was one of the worst times of my life,” Richard Oakes tells MOJO at his home studio in the west London suburb of Hanwell (“not very rock’n’roll, so it suits me down to the ground”), where the last three Suede albums have been written. “I was at an all-time low. So I took a lot of convincing to do the reunion. It took me months to decide, a lot of soul searching: Is this Suede thing going to drag me down again? Writing the comeback album was very difficult – it’s like painting a target on yourself. If Bloodsports had failed, you wouldn’t have heard from us again.”

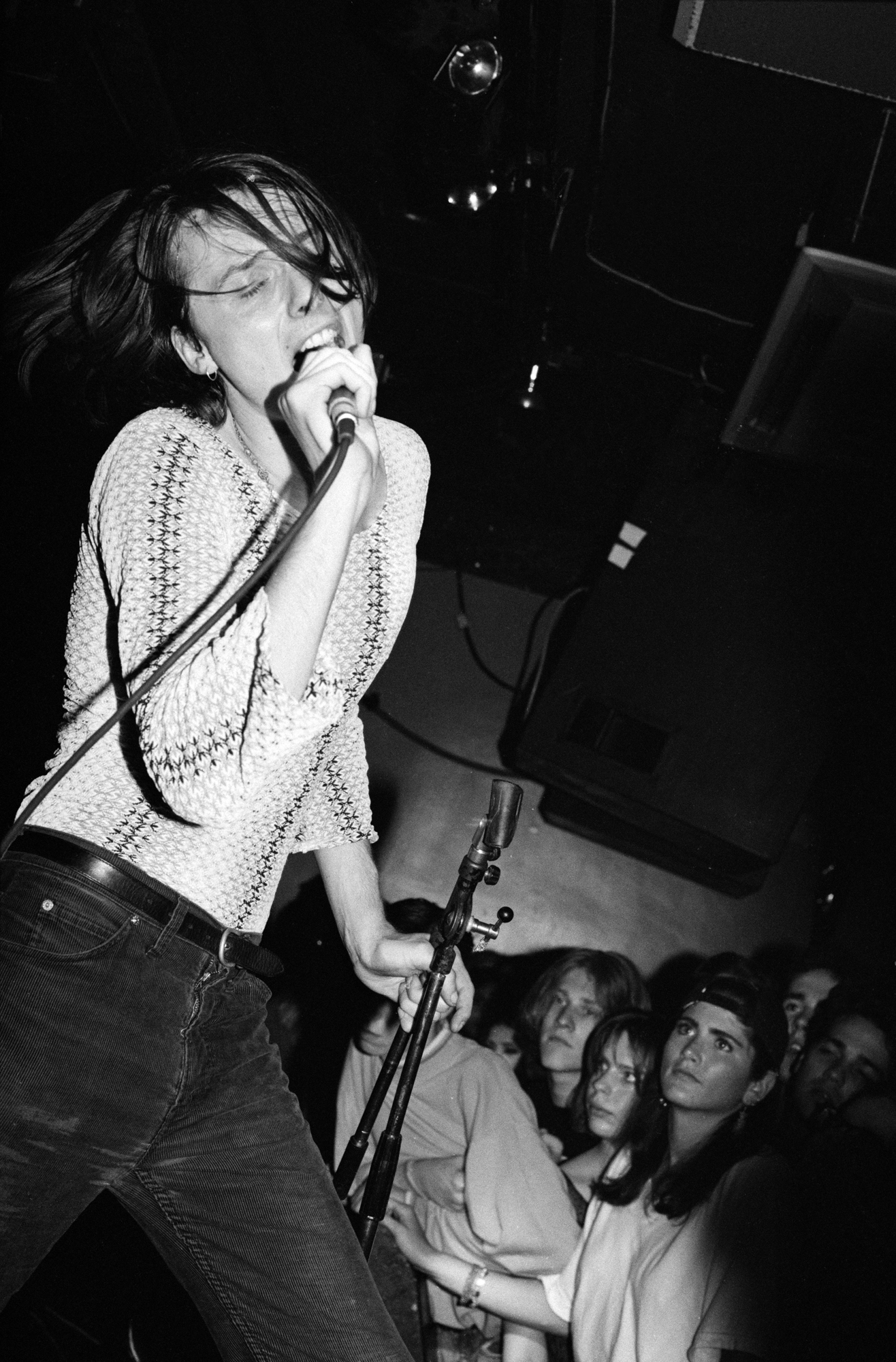

Anderson on-stage at London Camden Underworld, June 3, 1992.

Reuniting them with Ed Buller, producer of the first three albums but neither 1998’s fried Head Music nor 2002’s hollowed-out nadir A New Morning, Bloodsports pragmatically offered an older, wiser Suede. Although the album’s modest sales amid a transformed music industry landscape dispelled any notion that Suede could simply revert to the glory days, it did however restore them as a viable creative entity. Their next move would be a crossroads moment.

“I thought, Let’s embrace the fact that we’re not part of the mainstream,” says Anderson. “Let’s not make an accessible album, but deliberately do something a bit more conceptual and meandering.”

Repositioning Suede as an art-rock experiment in intensity and catharsis, 2016’s Night Thoughts was a mighty neo-gothic song cycle with orchestral undertones, launched at London’s Roundhouse with the band behind a screen, accompanying a film made by Roger Sargent. The warm reception from critics and fans, thrilling to the work’s evocations of full-tilt Dog Man Star-dom, emboldened the onward journey to 2018’s The Blue Hour, a loosely autobiographical piece where Anderson, now the father to a young son, explored the neuroses of parenthood amid haunted soundscapes pointing Suede further toward the abstract realm – exactly the direction a band in its mature phase is supposed to take.

Still, however, Suede couldn’t shake the grit from their shoe. When it came to touring The Blue Hour, Codling recalls audiences “standing stock still and nodding along politely”. Oakes, although “immensely proud” of the record, notes the proliferation of outside musicians and a disparity between the writing’s cerebral constructs and Suede’s intrinsic attributes. “It was difficult to put those songs across in a setting where it’s all about energy, adrenaline and direct injection of your personality.”

Not for the first time in his life, Anderson had gone too far. But now, with the benefit of age and experience, his analysis of the situation was clear-eyed, decisive… and quite unexpected. With three-fifths of the group into their fifties, Suede made their self-proclaimed ‘punk album’: recorded during lockdown then released in 2022 into a chastened world, Autofiction mainlined the febrile post-pandemic mood and was acclaimed by an audience starved of mass communion. It felt like what Suede had been missing too: a taste of the band’s primordial self.

“When we re-formed,” says Osman, “one thing we did was look at bands of our era, and bands that have re-formed, what they did wrong. What they always seem to do wrong was have this big static thing and the fucking orchestras and backing tapes and stuff. There was no sense of them being the band they’d started off as. And we’re always trying to get back to that – that physical feeling of the first time you’re in a band, making a racket, making yourself heard. Autofiction was very much made that way.”

Strictly speaking, the songs were more attitudinally ‘punk’ than they were, say, Live At The Roxy, but its raw sonics and emotional purging made for a Suede album unlike any other. Autofiction was launched with two tiny club gigs in London and Manchester under an alias, Crushed Kid: a new name for a new beginning. Standing stock still and politely nodding along to Crushed Kid was not an option.

“I always feel like we can stretch Suede and get arty and do unusual things,” says Anderson, “but it always snaps back to being a rock band. When you’re young, you want to come across as sophisticated, don’t you? The younger you are the more pretentious you are, because you don’t really understand these things. You’re using pretension as a mask. Then as you get older, you go, What music do I like? I do like some pretentious music. But what music do I really like? I like rough, angry passionate music. It’s like Picasso – he spent years painting incredibly sophisticated paintings, then went back to something primitive. If you stick around long enough, that’s an arc you’ll go through.”

“I took a lot of convincing to do the reunion, a lot of soul-searching: Is this Suede thing going to drag me down again?”

Richard Oakes

Brett Anderson’s Notting Hill abode is as bright and meticulously well-kept as its owner. While he busies himself in the kitchen, MOJO notes the Bruce Springsteen documentary paused on the television and the vintage record player midway through Joni Mitchell’s Clouds. Tea arrives in a Sex Pistols Pretty Vacant mug, brewed to the perfect blend of astringency and comfort. “Thank you!” Anderson exclaims. “I pride myself on my tea making. The key is to warm the cup beforehand, then it brews at 100 degrees. Whereas, if you just tip the water into the tea bag, it brews at 80-something degrees. Swish some boiling water in first and then put the bag in and it brews at that temperature. A top tip there from a tea bore.”

If Autofiction was “punk”, then Antidepressants is “post-punk”. That’s the official Brett line, at least. The truth is more nuanced: both the first and second records of Suede’s fourth act derive substantially from the spidery fundaments laid down at the end of the ’70s and the start of the ’80s by Magazine, PiL, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Joy Division, The Cure et al, links in the chain of being that nurtured Suede from its roots in the I’m-so-bored-with-Haywards Heath heads of “15-year-old Cult fan-club member” Brett Anderson and “teenage goth” Mat Osman.

“It’s the music of my and Brett’s adolescence,” says Osman, his six-foot seven frame nestled into a sofa in Suede’s management office near London’s Marylebone Station. “I mean, I had the full backcombed hair and paisley shirts and I loved the Banshees and The Cure. The first band I went to see a lot were Echo & The Bunnymen. But the weird thing is it’s Richard who’s written most of it, and he comes to that music as history.”

It was thanks to the Banshees, Cure, Bunnymen et al, that Mat Osman discovered David Bowie, Scott Walker and Leonard Cohen – the artists that Suede insisted new kid Richard Oakes imbibe upon joining the band in 1994. The irony being that thanks to his older sister’s collection, the teenage Oakes was grounded in exactly the same post-punk records at exactly the same impressionable age as his new bandmates, who were all at least 10 years older and publicly keeping quiet about their dubious pasts – with the exception of Simon Gilbert, a diehard punk from the Cook, Topper and Budgie drum school whose tribal rebel revelry transformed the proto-Suede when he joined in 1990 and which would introduce the band to the world with the opening tom rolls of The Drowners. (As per his preference for several years now, Gilbert declined to be interviewed for this piece. “He’s like royalty,” says Anderson. “He just waves from his carriage occasionally.”)

“The first couple of years I was in Suede was about fitting in,” says Oakes. “Like, ‘You have to be this type of person now.’ That went down to everything. I was expected to dress a certain way. I was expected to listen to certain records. They said, ‘What’s your favourite David Bowie album?’ I said, Well, I don’t really know, I think my mum’s got a copy of Ziggy Stardust…. So they bought me his back catalogue and said, ‘Learn this.’ I’d come straight from school and was basically a bedroom nerd, and that’s not cool. So I had to keep the bedroom nerd hidden, and create this cool, snotty, rock’n’roll attitude for myself. I look back now and it’s all a bit (winces), You could have just been yourself.”

Is it a stretch to suggest one reason for Oakes’s foundational template being so prominent now is that his Suede seniors feel a little guilty for bending him to the brand identity?

“There’s so much emphasis on the early version of Suede,” says Anderson, carefully. “And not enough emphasis on the current line-up. Richard is such an underrated guitarist. He’s been in the shadow of Bernard so much, because Bernard’s persona is so huge, and Richard never competed but quietly got on with just being brilliant. He was encouraged to make ‘Suede-like’ music, which meant he could never quite be himself as a guitarist. Autofiction is such a good record because it’s Richard. You’re hearing Richard for the first time. And again with Antidepressants, I wanted him to lead. Richard is the most natural musician I’ve ever worked with.”

Oakes has a more measured perspective.

“That’s very gratifying to hear. But of course, immediately my thought is, Well, I’ve put just as much of myself into all the other records. My teenage influences – Keith Levene, John McGeoch, The Fall, Wire – didn’t really have a place in the writing in the early years. And I had to wait. When we did Autofiction, suddenly I felt it did have a place. The frame of mind when we started writing Autofiction was, Let’s try and play to our strengths, be a band in a room again. One of the most prominent features of the band is the guitars. That’s why my presence is a lot more obvious than it was. Certainly wasn’t me elbowing my way to the front – because I’m just not that guy.”

Suede and their shadow selves, (from left) Oakes, Codling, Osman, Anderson, Gilbert, London, June 4, 2025

June 22, 2024. Midway through their set at the Isle Of Wight Festival, Suede debuted what would become the title track of their next album. A charged approximation of Sonic Youth covering Magazine’s Shot By Both Sides, the acclaim which greeted the song during a subsequent three-week co-headlining UK tour with fellow Britpop dissenters Manic Street Preachers indicated its significance.

“The response to Antidepressants was immediate, people were jumping up and down,” says Codling. “Two gigs later and people had learned the words! Only half the record was written then, and we took that as a sign we were going in the right direction. That’s why I think there’s more up songs, more angry songs, than you’d often find on Suede records. We realised the extent to which we leant on big, sweeping, romantic ballads was not necessarily what we needed to be doing at the moment.”

Codling is part of the Suede songwriting inner circle, alongside Oakes and Anderson. Sometimes the three work together in Hanwell, with the singer bringing along a specific idea for the others to work around – for example, Autofiction’s That Boy On The Stage – but more often it’s the Suede ‘new boys’ going down what Oakes calls “avenues of weirdness” then sending a piece of music to Anderson. If he’s inspired by it, he’ll write a song. And if he isn’t, the idea gets put aside. Or he does write a song, but it doesn’t pass the subsequent filters: Gilbert and Osman, then Ed Buller. Oakes estimates Suede have “hundreds” of unrealised first drafts for each album. In the Covid hiatus between Autofiction’s recording and its release, Suede wrote what they thought would be its follow-up – a ballet soundtrack, the polar opposite to the record they’d just finished. But such was the eventual response to Autofiction, the ballet idea was binned. Two of its grandiloquent mood pieces – Somewhere Between An Atom And A Star and Life Is Endless, Life Is A Moment – were, however, repurposed for Antidepressants.

“Songwriting is a strange puzzle to work out,” Codling states. “It’s about making the right choices. Towards the end of the ’90s there were lots of bad decisions made. That we got back together at all is like, We’ve got unfinished business. We still have to prove people wrong. There’s still records to be made. We know we can’t fuck up like we used to. If we’re making a record once every three years, you can’t have six years between decent records. So we can’t afford to make mistakes.”

New dog, old tricks (from left) Oakes, Osman, Anderson and Gilbert, New York City, November 1994.

The sleeve art for Antidepressants features the words “Broken Music For Broken People” imprinted in the shape of an X. Both the stencil block typography and the slogan’s elliptical logic suggest Brett Anderson paying tribute to his teenage love of Essex anarcho-punk pioneers Crass.

“It’s definitely a homage to Gee Vaucher,” he says. “Her artwork for those Crass albums is absolutely fucking brilliant. The Feeding Of The 5000 [Crass’s 1978 debut], I can just stare at that. I think she’s a genius. Bizarrely enough, we were going to do some work together for A New Morning, the last [pre-split] Suede album, but my head wasn’t in the right place and it didn’t work out. Lots of things in those days didn’t really work out.”

The grafitti’d wall on Antidepressants’ inner sleeve is a nod to the cover of the second Crass album, 1979’s Stations Of The Crass, while the scrawled words – “Desolation as an art”; “This life belongs to you”; “I look in my house it’s a luxury design but there’s shit on the walls that I’m hiding behind” – similarly evoke Crass’s negationist diktats. In fact they’re lyrics from three separate Antidepressants songs – Disintegrate, Sweet Kid and the title track – while “Broken Music For Broken People” was an album working title and the song of that name one of the thematic keystones. It’s in the Suede tradition of beautiful loser anthems such as 1996 hit single Trash, albeit with a very different sonic landscape: instead of druggy insouciance there’s fractious anxiety, a gleeful post-millennium psychosis.

“Thematically, it’s a lot different from Autofiction,” says Anderson. “More paranoid and neurotic. The little tannoy voices you hear going through the record was an attempt to reflect that sense of the 21st century where it feels like you’re being issued with commands the whole time.”

Like ‘Mind The Gap’ or ‘See It, Say It, Sort It’?

“Yeah, this sense of being a citizen in a benign yet oppressive world. When you get on the train, you’ve kind of been issued these commands, and then you put your headphones in and it’s ‘Connected! Disconnected!’. But also I like the joy in defying that control. Broken Music For Broken People is a the-weak-shall-inherit the earth song – a song of defiance. Like, if there’s hope, it lies with the proles, that kind of sentiment.”

Ghostdancing in the dark: Anderson and Codling, Berlin Columbiahalle, May 15, 2022

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith ultimately has his hope crushed by the machine. But before the bleak denouement, Orwell offered a dream vision of another country, the “Golden Country”, a half-remembered rural utopia that possibly never really existed. Suede’s version of the Golden Country is Dancing With The Europeans, its title inspired by a gig in Spain which lifted Anderson out of a low phase.

“It’s a ‘Heroes’-esque romp around Europe,” he laughs. “Well, a metaphorical romp. I’m well beyond the actual romping age, I’m afraid!”

Being that we are now deep into Suede’s black period, Dancing With The Europeans naturally features a flagrant suggestion of the introductory guitar riff from The Cult’s ’80s student disco staple, She Sells Sanctuary. Mat Osman looks pleased when MOJO extends the Cult analogy, suggesting Antidepressants could be their Love to Autofiction’s Dreamtime. “Totally!” he says. “Me and Brett loved Dreamtime. I saw them in Brighton on the tour before that, which would have been Death Cult. They were dressed completely in black. And the next time it was the full Native American stuff, properly loud and unashamed.”

He suddenly looks thoughtful.

“As I get older, music becomes more important to me. That sense of music, especially of live music, as being this joyous, elevating thing, that wipes away the grey of late-stage capitalism, it’s wonderful! As you get older, there’s less magic in the world. There’s less transcendence. But quite soon, when we start playing gigs, there’ll be a moment when I think, What the fuck am I doing? I’m a 50-something-year-old man, why am I throwing myself around the stage? I should be writing books, doing civilised things. Then something happens, a song goes off, and you see faces in the audience, people moving as one, and you just think, Fuck it. That’s it! I mean, that’s exactly it. And it’s truly anti-depressing.”

“We can stretch Suede and get arty and do unusual things, but it always snaps back to being a rock band.”

Brett Anderson

Much is made of the weaponry that Suede lost during the band’s first two phases. Understandably so, because both Justine Frischmann and Bernard Butler are significant figures whose departures had major ramifications. When future Elastica frontwoman Frischmann left in 1991, frustrated at her preferred vision being drowned out, Butler raised his game, without which Suede would never have emerged from London’s early-’90s indie morass. Butler’s exit threw the band into crisis, forcing a panicked rebuild that should never have worked, yet somehow did. Would Suede be such a potent force 30 years on had either of those two stayed, or indeed had anyone else other than Richard Oakes or Neil Codling joined?

Today Suede are, in Codling’s words, “a cottage industry”. They self-finance each album, recording in brief, intense, diligently prepped sessions. Budgets are tight and resourcefulness a must: the guitar parts for Autofiction and Antidepresants were laid at Benny Andersson’s RMV Studios in Stockholm after Richard Oakes’s Swedish wife negotiated a half-price deal. “This is the new reality,” Oakes says. “Back in the ’90s, we’d be funded to spend months and months in the studio, where we were just sitting around reading the paper and smoking. And rather than complain about how great it was in the old days, we make it work now, in the present.” He pauses. “It wasn’t so great in the old days anyway. Piling money onto a bunch of irresponsible young men is not a good idea.”

As the author of 2019’s traumatic rise and fall memoir Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, Brett Anderson can certainly attest to that. It seems fair to suggest the vitality of his and Suede’s present is a function of just how fast they rose and how hard they fell. The sleeve of Antidepressants features Anderson silhouetted between two animal carcasses, in tribute to the famous 1962 Vogue photograph of Francis Bacon. Not exactly subtle – but that’s a luxury Suede can no longer afford.

“It’s about mortality, the fragility of life, the fact that we’re not here for long,” Brett Anderson says with a smile. “I’m plummeting towards my sixties, and it’s terrifying and liberating. There’s not much time left. Get your shit together.”

Antidepressants is released September 5 via BMG. Suede Takeover is at the Southbank Centre throughout September 2025. Full info at suede.co.uk.

IMAGES: Kevin Westenberg