Mojo

FEATURE

Jim Keltner

The Master Drummer to Dylan, Lennon, Neil, Lana Del Rey and dozens more has come through overdoses and epiphanies to be the heartbeat of the greatest rock and pop. His secret? “It’s allowing the music to blossom,” says Jim Keltner.

Interview by Bob Mehr

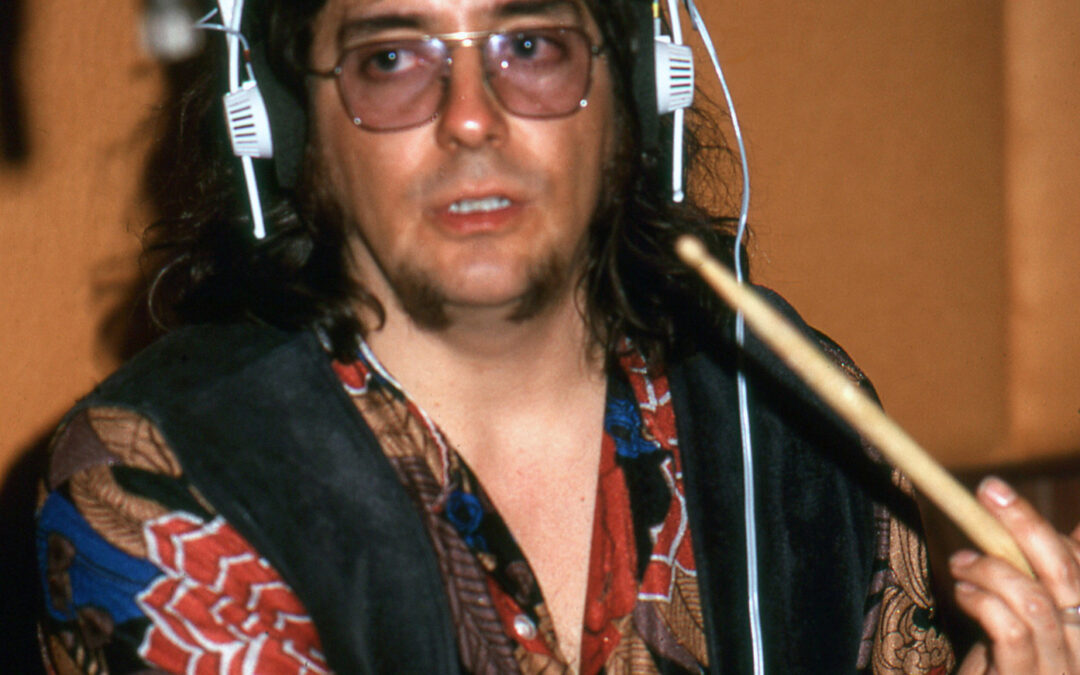

Jim Keltner in June 1971, working on American blues singer and guitarist B.B. King’s album ‘B.B. King In London’

‘‘THE MOST IMPORTANT THING IN MY career,” says Jim Keltner, flashing a grin, “was being thrust in the middle of so many geniuses.”

One could argue that the most enduring, versatile and prolific drummer in rock history is underselling himself. John Lennon and George Harrison, Bob Dylan and Neil Young, and more besides, probably would too. But Keltner’s having none of it. “Playing with those guys,” he says, “I really couldn’t go wrong.”

It’s a balmy spring day in Los Angeles, and Keltner is meeting MOJO at his unofficial offices, Drum Doctors, a rental and storage facility used by some of the top percussionists in the business. Entering the airy warehouse space, Keltner cuts a familiar figure in his signature aviator sunglasses. The shades are less rock star affectation than a by-product of Fuchs’ dystrophy, a condition which led him to undergo a pair of corneal transplants over the last decade.

Born in Tulsa – to a white Okie father and Mexican mother – Keltner grew up in Southern California where, in the mid ’60s, a chance encounter with teen pop hit-maker Gary Lewis thrust him into the hothouse of the Los Angeles studio scene. By the late ’60s, after turns on the road with Delaney & Bonnie and Joe Cocker, Keltner would follow fate into the most rarified musical circles, as an invaluable ally in the solo careers of Lennon, Harrison and Ringo Starr. In addition, he’s maintained decadeslong collaborations with Dylan, Eric Clapton, Ry Cooder and Randy Newman, helped define hits for everyone from James Taylor to Steely Dan, and remains a talisman for a whole new generation of stars eager for the Keltner touch.

With his 80th birthday approaching, Keltner is in a reflective mood, ruminating on a life filled with musical magic and coloured by loss. He rattles off a long list of felled friends, from childhood pal Albert Stinson (a gifted jazz bassist taken by heroin at age 24) to his early mentor Jim Gordon (the Derek & The Dominos drummer consumed by mental illness, and later sent to prison for killing his mother), and victims of drug and alcohol abuse including Jesse Ed Davis and Carl Radle.

“I sometimes wonder why that didn’t happen to me,” says Keltner. “I’ve died twice that I know of, and came very close another time, from overdoses, and I’m still living. That’s one miracle. There’s been many other kinds of miracles I’ve experienced. The main one being my wife.”

Keltner and spouse Cynthia met in junior high school in Pasadena in the late ’50s, and have remained together ever since. “I probably would’ve had a similar fate to some of those guys if it hadn’t been for Cynthia,” he says. “She’s always been my grounding.”

‘Sensitivity to the songs’ is invariably cited as Keltner’s USP, but that’s not all he’s sensitive to. As he looks back with MOJO over his life and career, the master drummer finds himself choking up more than once.

“You know, I read somewhere that when you get older you cry more easily. I’m finding that’s true,” he says. “I’ve always been a crier, anyway.”

Levon Helm, Ringo Starr, Alex van Halen, and Jim Keltner in the early 1990’s, wearing sunglasses

What are your earliest memories of music?

My dad’s collection of old 78s. There was R&B stuff like [Louis Jordan’s] Saturday Night Fish Fry, with great singing and real funny lyrics. Then there was Benny Goodman records with Gene Krupa. There was a song called Disc Jockey Jump, with Krupa playing an arrangement by Gerry Mulligan. If I played it for you right now, you’d think it was recorded last week. It’s very modern, especially the drum sound. I always tried to emulate that. To this day, I still emulate that sound.

Seems like you came from a rhythmic family background.

My dad was a drummer. He met my mom at a recreation centre in Tulsa, playing for a dance. When they got married, he sold his drums to get some money. And she warned him: “One of these days you’re going to have a son and he’s going to want some drums” (laughs). My mom’s brother, my uncle Willie Mendoza, played bass.

What was your childhood like?

Growing up it was me and my sister, Judy Kay. We had lost my little sister, Jacqueline Marie. She died when she was six and I was eight. And it killed me. It killed a part of my soul. The day of her funeral, I went up and saw her in the casket and started crying. I just cried forever it seemed like. Then I remember they were bringing my mom out, my dad and my uncle were carrying her. My mom basically had a nervous breakdown. So they sent me to be with my aunt and uncle and my cousins, down in the swamps in Louisiana, for a while. It was a great distraction.

You began playing drums just as you hit your teens.

My dad was a Shriner and they had a marching band, he was one of the drummers. My mom took us [to a parade] one time and we sat on the curb on main street. As they came closer the sound of the drums just filled my whole body. That piqued my interest. I went with my dad to a rehearsal in the basement of this Shriners club. And they were all old men – like in their thirties (laughs) – smoking cigars, drinking Scotch and telling dirty jokes. I listened to them play and practise all night, doing their cadences. At the end of the night, I picked my dad’s drumsticks up and played the exact same things I had heard. They were all impressed and my dad was impressed. That was obviously a big moment. That’s what prompted my dad to get a drum set for me.

Just a few months later, your father uprooted the family and moved to Southern California…

One of the reasons was my mom. She was sneaking out with my aunt Connie to Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa all the time. They loved dancing. My dad was a hard-working guy and had two jobs – he was a painter during the day and at night he was a Deputy Sheriff. He called Tulsa “this godforsaken place”. I don’t think he meant it. But we left for California with a tiny little trailer hitched to the car. He had a gig lined up in Santa Monica, but it fell through. My mom said, “Let’s go back – they all said you’d be right back just like everybody else.” And that pissed my dad off. So we stayed another day and sure enough he got a job at Santa Anita racetrack. We ended up moving to Pasadena.

“I thought I’ll never be as good as Mike [Romero], so why should I keep trying? I was ready to quit.”

Jim Keltner

Were you always determined to be a professional musician?

No, I was a baseball player, a pitcher. I was really good. For me, the drums were fun but it wasn’t as big a deal as baseball. Then this strange thing happened where I would be playing, working up a sweat, especially in the sun, and I would break out in hives. I was young and athletic, and it made me crazy. One day, I mowed the lawn, and went to get a haircut, and rode my bicycle up to the barber. While I was sitting in the chair, I started breaking out again. It got real bad, and I passed out. Not only did I pass out, but my lips swelled up massively, my ear lobes swelled up, my neck started to swell, my eyelids swelled shut. The barber panicked and called the paramedics. By the time they got there it had worn off. That led me to becoming a guinea pig for the doctors at UCLA, who were studying this condition, urticaria – they’d never seen it come on so violently and then disappear after 20 or 30 minutes. They were developing an antihistamine at the time and had me testing it. That was the thing that transitioned me from baseball to drums. Drums became the full-time passion.

You grew up in the rock’n’roll era, but pretty soon you were hooked on jazz.

Like every other teenager, I liked the songs on the radio at the time, doo-wop and early R&B. But then I met my buddies who were jazz guys, hardcore jazz snobs. My very best friend in life was Albert Stinson. He ended up playing [bass] with Miles Davis. Albert was my main partner and we’d go see music. I fell in love with Elvin Jones, big time. We’d see all these drummers – Shelly Manne, Irv Cottler – guys who lived in LA and would be in different places playing. My problem was there was another drummer named Mike Romero, a guy who lived around us, and he was just incredible. I thought I’ll never be as good as Mike, so why should I keep trying? I was ready to quit. But Albert said to me one time, “You’re going to be a great drummer someday.” Because he said that, I didn’t quit. He saved me and I stuck with it. Later, he got me my first real jazz gig with John Handy.

But fate intervenes and you join a Top 40 pop band, Gary Lewis & The Playboys…

When I joined, I went from making $85 a week to $250 a week. First thing I did was buy a brand-new Corvette (laughs). But talk about fate. Gary changed my whole life. He comes into the music store where I work, and he just happens to be the son of my favourite entertainer in the world, Jerry Lewis. I loved Jerry – used to cut my hair like him for years. Suddenly I’m at his house in Bel Air once a week rehearsing. Playing with Gary, that put me on the path to the pop, rock world.

You only lasted a year or so with Gary – at which point you got fired.

I became really full of myself. I’m this young cute kid and I could be a little funny too – I was trying to be Jerry Lewis (laughs). So I would get all the attention. Pretty soon at the press conferences, I was getting too many questions. So I got fired. But that was a great lesson. A very important lesson in learning how to behave when you’re the sideman as opposed to the star.

You soon fell into a studio scene in LA that, coincidentally, was filled with a bunch of your fellow Tulsans.

When I met Leon Russell he said, “Oh, you’re an Okie too?” There was this whole Tulsa clan in LA, and they took me in and showed me what I should listen to and how to play. Being in that environment, I got to learn up close from the most incredible drummers: Hal Blaine, Earl Palmer, Chuck Blackwell. And then eventually Jimmy Gordon became kind of an idol of mine. I loved the feel and precision of his playing.

In the late ’60s you joined up with Delaney & Bonnie – but they fired you too.

We were scheduled to do some TV show and I had booked myself a flight to New York to do a record with Gábor Szabó and Lena Horne – and I wasn’t going to miss that for anything. I said to Delaney, I got to go do this thing – I can get a sub, I can get Jimmy Gordon, I can get anybody you want. And he said, “Nope – you’re the drummer.” That ticked me off. So I left. The next day when I was at the hotel in New York I got the call: “You don’t have to come back.”

You bounced back, though, with Joe Cocker and Leon Russell on Mad Dogs & Englishmen. That seemed like an incredible circus.

Playing with Cocker, this white version of Ray Charles, he was just on fire then. You had Leon as the musical director and all these great musicians and singers in the band. The reviews and the response was astonishing. It was incredible, but not sustainable either. The lifestyle took over pretty quickly and it got nuts.

“John [Lennon] was so full of life and so full of energy in the studio… Being on the same page, loving what we were playing and hearing, that’s how the friendship was born.”

Jim Keltner

You landed in England playing with Eric Clapton – the start of your ‘Sideman To The Stars’ career. Was that ever intimidating, working with someone who was considered ‘God’?

Clapton had really been enamoured of Delaney & Bonnie and he came in and basically became one of us. Eric was the first big English star I worked with, but he was such a normal dude – he just wanted to play and hang.

It was another stroke of good luck, through Clapton, that led you to John Lennon…

I was staying at Eric’s house in Surrey. We had been recording in Barnes, in London at Olympic, and getting back really late. One morning the phone kept ringing and no one was answering – and for some crazy reason I decided to pick it up. It was Phil Spector and he wanted Eric to come play on a [Lennon] session. I didn’t want to wake Eric up. And so Spector just said, “Well do you want to come and play on John’s record?” And I didn’t know it was Imagine – it didn’t have a name yet. Couple days later I’m in the studio with John and Phil. The very first song I played on was Jealous Guy.

You got very close with Lennon and played on nearly all his albums until the end.

John was so full of life and so full of energy in the studio. And, obviously, he was John Lennon so his songs were just killer. Being on the same page, loving what we were playing and hearing, that’s how the friendship was born. And I was very close with John. He was in our lives so strongly, me and my wife. It was like, How did this even happen? Everything happened so fast in those days, you know? When John took that break [in the mid ’70s] he partially did that to save his own marriage. He had gotten really out of hand – we all had. He had his son Sean and then him and Yoko made the Double Fantasy album without us – me and [guitarist] Jesse Ed Davis and [bassist] Klaus Voormann. But I have a letter that John sent, a mimeographed letter, we each got it, and he says, “Guys, we’re gonna get back together very soon. I want to make another record.” But he was gone not long after that. You can’t imagine the frustration of knowing we could never make music again or just be around him. There was nobody like him.

You developed a similarly close relationship with George Harrison, playing on all his records. Why do you think John and George – who could’ve played with anyone – stuck with you?

I always felt that John and George were huge fans of Dylan, and huge fans of Ry Cooder and Randy Newman, and they knew my association with those guys. That was one of the things that worked in my favour.

And, of course, in the process you also connected with Ringo Starr. Was that awkward initially since you were taking his place in a way?

Going back to the ’60s, every time I would hear a Beatles record I would be amazed at the drumming. It was not powerful, it wasn’t precise, but it was still serving the music in an amazing way. That’s what I wanted to do. When I met Ringo, he embraced me, which I really appreciated. I didn’t want there to be a negative vibe. But we got close and talked constantly about drums and drumming. I remember Ringo telling me he was [naturally] left-handed and that’s what made him go for a fill in a different way. His time feel, where he felt the time, was the beauty of it.

It’s interesting that although you’re obviously highly skilled, you’re not known as a technical player either.

On one hand, I was affected by the guys who did have that wonderful technique and I wanted that. But on the other hand, I would hear someone like Ringo or Charlie Watts or – God bless him – Levon Helm play, and I would realise, it’s really about the music, and how you allow for the music to blossom. Maybe get out of the way. I did an almost systematic undoing of technique in my playing for many years.

Leon Russell first brought you in to work with Dylan – cutting Watching The River Flow and When I Paint My Masterpiece – in 1971. What was that experience like?

For me, at the time, Bob wasn’t that big of a deal. I had a sense that Bob liked not being a big deal. He wanted to not be a big deal. In the control room, standing next to Bob, I felt comfortable enough to say something really stupid. I said something – unbelievably – like, “Bob, I hear you got a lot of kids” (laughs). I remember distinctly, he didn’t acknowledge it in any kind of way at all. I was thinking, “Why did I say that? Why did I say anything?” I learned my lesson with Bob to just be cool.

How does one maintain a 50-year relationship with Bob Dylan?

Bob is really particular about the people he plays with. He can tell if you’re listening to him, or just there, or playing for yourself. He has a trust in me and vice versa. You can’t play your very best without a certain amount of trust, otherwise you just go on automatic. And automatic is not a good thing, especially in the studio. What’s so unique to me about Bob is his vocal phrasing. His phrasing is not that of a rock singer or a crooner. He’s more from the jazz world than he is from anything. That’s the way I think of Bob. He told me he came up in those [New York City] clubs, used to do gigs with [jazz pianist] Cecil Taylor, that’s the kind of stuff he was exposed to. That’s one of the things that drew us together musically.

Jim Keltner in studio 1973 in Los Angeles, California

You were there for Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid…

When we did Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door, that was such a moment. We were in the dark, looking at a big screen with the film showing, and Bob’s playing this song, with these

changes, and those words. My God! Then, the fact that Katy Jurado, the Mexican actress, she’s got these big ol’ eyes like my mom, and her husband is this white guy, this sheriff, and he’s dying at the edge of the river. And Bob’s singing… and, man, I just started crying. I’m playing, but I’m crying hard. And I’m thinking, “Don’t blow it, don’t blow the take!” A few years later, I did Short People with Randy Newman. And I was in the same situation, but I was laughing instead of crying. I was hearing Randy say these words that had me cracking up, and I’m thinking, “Don’t ruin it, this is a good take!”

You largely avoided touring for most of the ’70s, but ended up going on the road with Dylan for a couple years at the end of the decade during his Born Again period. What prompted that?

I stayed off the road for all the obvious reasons – mainly I was working almost every day in the studio. With Bob, he asked several times for me. He never said in so many words, “Come on the road with me.” He’d say, “You want to come down and listen to the new record?” Maybe to see if I’d like it and go out with him. Because of that I got to listen to a couple of his records before anybody, just hanging with Bob. With [Slow Train Coming] the instructions were for me to listen to the record, and then come up and see Bob in his office afterward. I sat down and started listening. There were all these songs about Jesus. It’s like, “What? What is he saying? What’s happened here?” Suddenly, I was crying like a baby. Crying uncontrollably listening to these songs. There was a box of Kleenex sitting there – I don’t know if Bob knew I’d need it, but I went through that whole box. Later on, some real Christian friends of mine called it the anointing: “The anointing was on you.” I got up after the last song, walked upstairs – and I had never been into the room where he wrote – and opened the door and he’s sitting there typing. I just remember telling Bob, “Wherever you’re going or whatever you’re going to do, I want to go do it with you.”

Sounds like you were profoundly affected.

On the road, I’m being hit in the head every night with these songs, and you would’ve thought I’d want to be like Jesus, to be more like what he talked about. And I actually went the opposite way. But when that period was done and I got back to normal life, it had changed me. I had real feelings of connection, spiritually, that I know I didn’t have before that tour. I think this was fate. This was another one of those fateful things in my life that involved Bob Dylan. How many people can say that?

Among the other big figures who’ve enlisted your services is Neil Young. You’ve done some great work with him over the years, particularly in the early-’90s where you and Booker T. & The M.G.’s backed him on tour.

I always told Neil how much I loved Crazy Horse. I saw them play a couple times live and I was amazed at how they – with hardly any effort really, and not a great deal of facility – made his songs come alive in such a compelling, honest way. For me to be able to play with Neil, I just wanted to do that. In the studio we did a record that was very tame, [2000’s] Silver & Gold, but it had really cool songs. When I would hear things back, I’d think, “Oh I wish this was more like Crazy Horse” (laughs). But I found myself having a whole lot of fun playing with Neil live. And I realised playing with him was like playing with a jazz guy too. More than I would have thought.

Remarkably, after six decades, you continue to be the go-to session drummer for a whole new generation of artists – people like Phoebe Bridgers, Jenny Lewis, Conor Oberst, Perfume Genius…

The latest one was Lana Del Rey. I knew her name but didn’t know her music or anything. And my great grandkids, a few weeks ago when they were here, said, “Grandpa, who are you playing with now?” They love that I played with the guys in The Beatles – to them that’s a big deal. Anyway, I just mentioned Lana to them. “You played with Lana Del Rey? You played on Watercolor Eyes?” – that song is in the Euphoria TV show. And I don’t know Euphoria, but that’s one of the most popular shows for their generation. That day in the studio with Lana, I discovered she’s got one of those amazing voices.

You don’t carry yourself like someone who’s 80. What’s your secret?

Since I’m a kid and my little sister died, and everybody was trying to comfort me, people would say, “You just gotta pray and everything is going to be OK.” My aunties would say that, my mom – “Just pray, honey.” There’s never been a time when I sat down behind the drums where I didn’t say a little prayer. Never a big crying kind of prayer, just a little thank you for making this great. There was a long period in the studio where I would go, “God, help me to play better than I’ve ever played in my life today!” (laughs). For years, I never really believed it, it was just something I did. But as time went on, and the more I look back, the more I know God has answered every prayer I’ve ever had. I think you need to have a spiritual connection – and music is the greatest form of spirituality there is.

This article first appeared in the August 2022 issue of Mojo

Images: Getty