Jimmy Page: I wanted Led Zeppelin II To Be Extreme

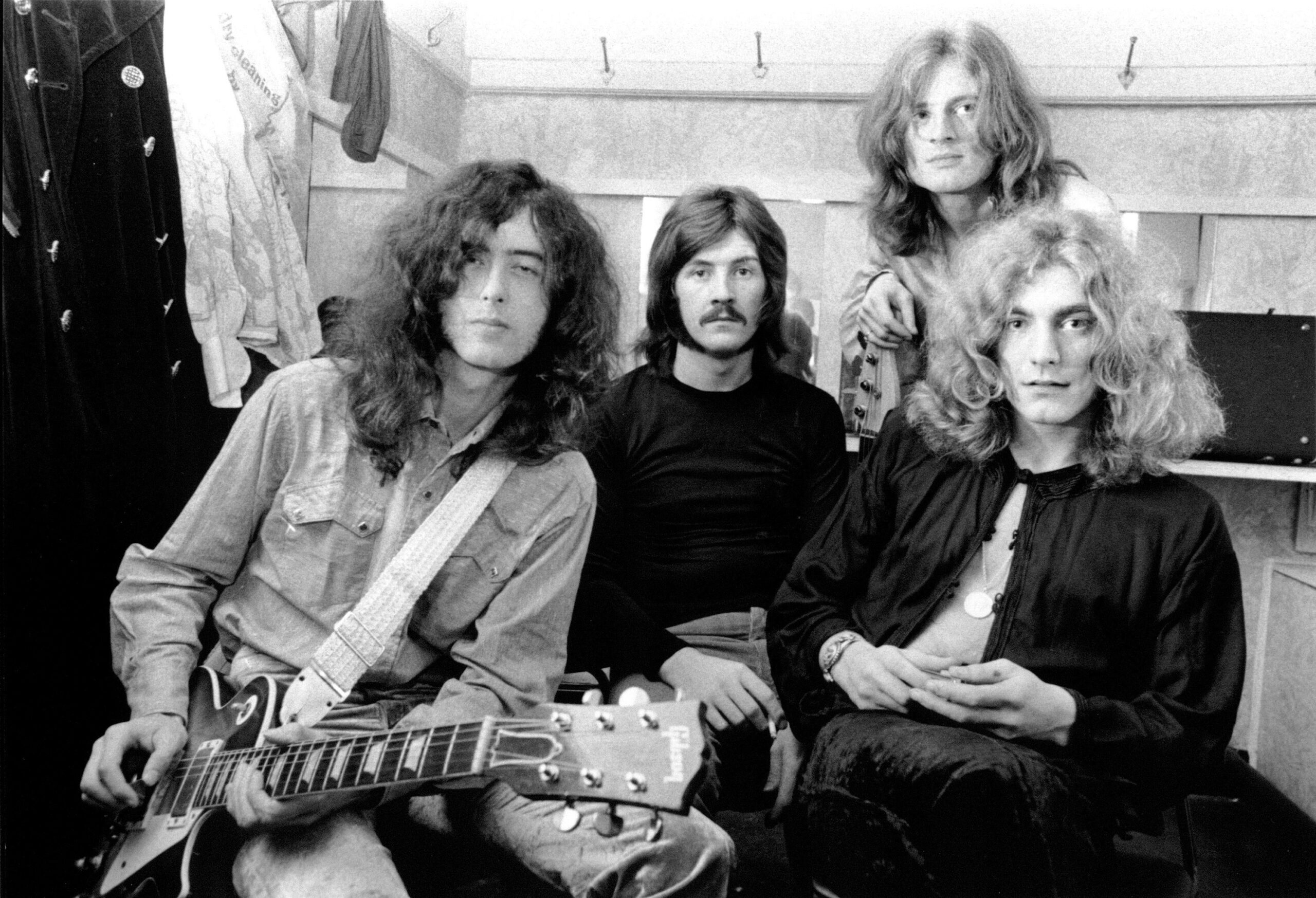

On the anniversary of their second album’s release, Jimmy Page looks back at Led Zeppelin’s rise from Brit blues wonderkids to globe conquering rock titans.

Slammed by the press, loved by the fans, Led Zeppelin became the biggest band of the ‘70s in the space of two years. In this classic interview from the MOJO archives, Jimmy Page re-lives the victory procession of the band’s second and third albums…

“Robert Plant was really into history. He probably had an A-level in it at school. He knew about the Norse legends, and the Vikings were quite a thing for him,” smiles Jimmy Page. “So when we went to Iceland – the land of the ice and snow – and then once he heard the riff I’d come up with, the riff became a vehicle for his words.”

The words in question accompany Page’s scything, staccato riff to Immigrant Song, the super-charged opener to Led Zeppelin III. Down the years ill-informed critics have attempted to draw convoluted parallels between Plant’s depictions of Viking raids and the Odin-styled rampage that accompanied the band’s seemingly unstoppable rise. “Valhalla, I am coming!” – Plant’s exaltation at the end of the first verse appeared to reflect the singer’s status as the self-proclaimed Golden God.

As Page states, however, the inspiration behind the song is more prosaic, dating back to the band’s visit to Iceland in June 1970 when Led Zeppelin took part in the first ever Reyjakvik Arts Festival. The brainchild of Russian-born classical pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy, the festival stretched over several days, and used different venues to showcase the arts, both local and global, across multiple disciplines, with Zeppelin ambassadors for British music.

Their visit came close to being cancelled following a nationwide strike when labour unions who’d downed tools following the repercussions of an economic crisis dating back to the near-collapse of the fishing industry – Iceland’s primary source of income – two years earlier. Local university students, however, rallied to ensure that the 4000-capacity Laugarddalshöll venue – which had been used for a trade fair prior to Zep’s arrival – was ready to accommodate the visiting British rock band whose set proved to be mind-blowing.

“Listening back to that show at the Olympia was quite something”

Jimmy Page

Six days after their Icelandic trip, on June 28, Zeppelin played Freddy Bannister’s Bath Festival in Shepton Mallet, topping a bill that featured largely American artists including Jefferson, Airplane, Frank Zappa, Santana, The Byrds, Dr John and Hot Tuna.

“It was bloody freezing! That’s why I was wearing a coat and hat!” laughs Page, remembering the occasion and explaining his Farmer Giles get-up. “But it was a significant show for us in England and it showed what the band were really capable of. We started with Immigrant Song. I mean, that’s it! There was this pulse coming out, and then this shriek from Robert. It was fantastic stuff! There was real drama to it. And then, later in the set, we did an acoustic set. We hadn’t been able to do it before.”

In front of a stunned audience estimated at 200,000 people, Page, Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham played for close to three hours, moving far beyond the hard rock sound that had defined their first two albums. As they prepared to record their third album, Led Zeppelin were entering a brand new phase.

“There’s a little casket that I kept my riffs in,” deadpans Jimmy Page. “Whole Lotta Love was in there, and then out came the Immigrant Song. It’s the intensity of that riff that gets you, isn’t it? You could stay on it forever. It’s relentless.”

Following a convivial lunch in a nearby park café, Led Zeppelin’s guitarist and producer is sitting in the annex of his Holland Park residence, discussing his ability to create instantly identifiable chord patterns. On the coffee table in front of him sits a folder, its laminated pages festooned with notes detailing recording dates and information relating to the material on the companion discs that accompany the deluxe editions of Zep’s new remasters which Page has overseen. The first three albums emerged on June 2 to much fanfare and the band’s catalogue will emerge sequentially over the next 12 months. For Page, as ever, restoring Zeppelin’s music has been a labour of love.

“Listening back to that show at the Olympia was quite something,” he says, referring to the live disc that accompanies Led Zeppelin’s self-titled debut album, released in January 1969. The October 10 show precedes the release of Led Zeppelin II by 12 days but includes Heartbreaker and Moby Dick on what is an ever-evolving set.

“You can hardly call what happened to us hype. We went out and worked hard.”

Jimmy Page

“We’d add songs to the set as soon as we had them. It was important to keep things exciting like that, but when you listen to the band at that show you can hear just how dynamic the playing was,” he nods.

The speed at which the Zeppelin camp moved is underlined by the fact they went from their first rehearsal in August 1968 to recording their first album and on to securing a deal with Atlantic Records in less than four months. The label’s press release heralding their signature heralded confirmed the “substantial” nature of the deal. The PR fanfare continued by stating that the hitherto unknown band were undoubtedly capable of following in the footsteps of Cream and Hendrix. Rather than enhance Zep’s reputation, these pronouncements appeared to antagonize the gentlemen of the press, none of whom had been given the opportunity to champion the band and who objected to the sense of hype which the label seemed willing to engineer around them. The situation was enflamed when certain journalists read the small-print on the album’s sleeve and found that the fledgling band had named their publishing company Superhype.

“It was tongue-in-cheek,” protests Page. “You can hardly call what happened to us hype. We went out and worked hard.”

By the time the self-titled debut emerged, Led Zeppelin were on the road in America supporting Vanilla Fudge. It was at that point that John Mendelsohn’s review of their debut album appeared in Rolling Stone, dismissing the notion that the band could “fill the void created by the demise of Cream.” Page was described as “a proficient blues guitarist” but “a very limited producer and a writer of weak, unimaginative songs” while Plant was is both “prissy” and “foppish” and, on How Many More Times, guilty of “unconvincing shouting.”

“I was surprised that it was negative to that degree and how cutting it was,” says Page. “It wasn’t just sticking in the knife, there was serious twisting involved. But I knew it was unfounded and that he just didn’t get it. I mean, there are some bands people bloody hate. It’s like Marmite syndrome. But with this, you couldn’t deny what we were trying to do, and that we were trying to move the boundaries of what music was.”

If certain sections of the US press sneered at Zeppelin, American audiences themselves didn’t seem to care. “You could see that bad reviews didn’t affect what people thought,” says Page. “The audiences were growing. We were playing small clubs at one point and there were more people outside than inside, so we knew things were happening.” Indeed, between late December ’68 and the end of ’69, Zeppelin toured the US no less than four times – something which in itself came with its own problems back home.

“People said we’d abandoned England but we hadn’t. I’ve lived in here all the time. But I saw the situation developing over there and I was fresh on that whole climate. It’s like actors these days, you go where the work is and in this case the work was in America,” says Page, reflecting on a period during which Zeppelin graduated from underground clubs such as the Grande Ballroom in Detroit and Miami’s Thee Image Club to convention centres and numerous outdoor US festivals.

“When we came to put II together, I already had the construction for Whole Lotta Love”

Jimmy Page

Page, who is naturally shy and reserved but whose evolving, dandified pre-Raphaelite image is evident from pictures of the time, admits that Zeppelin’s first few US tours were key to the band’s development.

“Oh, absolutely, my playing went up a notch, or several. All of our playing did and we began to realize just how good the band really was,” he says. “There was real alchemy involved because we were playing the whole time. There were four really strong character musicians, with strong identities, who also had the intellect to really stretch things out and make things come together.”

In late autumn 1969, with the band’s debut moving up the US chart following their third US tour, Zeppelin took a short break before reconvened at Page’s house in Pangbourne, Berkshire, to begin work on their second album.

“When we came to put II together, I already had the construction for Whole Lotta Love,” says Page. “We were working and familiarizing ourselves with that. What Is And What Should Never Be was the other song that we had, and that sort of tells you that we knew were we wanted to go from quite an early stage in the process.”

Initial recording began once again at Olympic Studios in South West London, with Page producing and engineer George Chkiantz – known for his work with the Small Faces and the phasing on Hendrix’s Axis: Bold As Love, in particular – assisting on the basic tracks for those two tunes. Then came the idea to continue recording while the band were on the road, with Page in particular relishing the idea of using a number of iconic American studios where some of the band’s favourite records had been made.

“We recorded in lots of different studios,” he nods. “A&M Studio in LA is where we did the overdubs for Whole Lotta Love, but we went to Mirror Sound where Del-fi records had been and where Chan Romero and Ritchie Valens had recorded. It was a really fine studio, a really live-sounding studio. In there we did the Moby Dick because it was just perfect for drums. The Lemon Song was done in there as well.

“I wanted to record at Gold Star but the rotary pots really weren’t very good,” he adds, on the subject of the studio in which Phil Spector crafted his Wall Of Sound and where the Beach Boys recorded much of Pet Sounds. “We did actually do something there [pausing] which has got lost… so we don’t want people searching for it, do we? But, I was keen to do all those real milestone places and stamp it in with the real Led Zeppelin hallmark. It was a way of paying homage, if you like.”

Despite the band’s relentless touring schedule, Page retained his studio focus and ensured that Zeppelin’s sound remained consistent, despite the variety of locations he employed to record.

“We were going for studios where the acoustics were very good when you played the music live,” he explains. “I wanted it to be quite extreme and that’s what I was going for: something that showed all the peaks of what we could do. I could really hear the acoustics in John Bonham’s playing and I knew that the more space we could allow that, the better it was going to sound. If you listen to II, you can hear that, and you can hear the character in the studios themselves on that record.”

“If the ‘60s had belonged to John, Paul, George and Ringo, the ‘70s would belong to Jimmy, Robert, John Paul and John”

A key moment in the album’s development emerged with the writing and recording of the semi-acoustic thrust of Ramble On, which Page, referring to his notes, confirms was recorded at Groove Sound in New York.

“It was starting to get interesting at that point because you’ve got the acoustic rolling through, and there’s the drums, the bass and the electric guitar so it’s as case of ‘OK. Is it going to start on an acoustic or an electric?’ In this day and age you’d just have a click track and you would just lay things on, but back then we had to do proper planning to make it work.

“As far as that intro goes [beats out the rhythm pattern on his knees], do you remember Everyday by Buddy Holly? Well, that was the idea behind that. I could go through loads of points of reference for some of these tracks but I’m not going to. The guitar part as we know it, it didn’t happen immediately. I could sort of hear it before I played it, but Ramble On has got these textures, some of which are guitar-led, but John Paul Jones’s bass playing is just superb on that track. Just the whole vibe of it is incredible. It’s got it’s own character that is only peculiar to itself.”

Led Zeppelin II was released on October 22, 1969 and topped the US charts, deposing The Beatles Abbey Road from the top slot en route to selling 12 million copies Stateside. By February 1970 it had also topped the UK album chart. Forty-five years on the symbolism that surrounds Led Zeppelin II remains unavoidable: if the ‘60s had belonged to John, Paul, George and Ringo, the ‘70s would belong to Jimmy, Robert, John Paul and John. Unlike The Beatles, however, Led Zeppelin did not rely on singles to promote their albums.

When an edited version Whole Lotta Love was released on 45 following demand generated by endless US radio play of the album track, the band themselves recoiled, forcing manager Peter Grant to tell Atlantic in no uncertain terms of their displeasure.

“Singles were for AM radio stations and we weren’t interested in that. We were looking for FM radio play where they would play whole sides of albums,” says Page. “That meant that in some cases they would play 20 minutes of your music. That’s how we sequenced II, to ensure listeners wouldn’t get bored. The album reflects the energy of being on the road. I know it tells on the record.”

As Plant’s libidinous display on Whole Lotta Love underlines, Led Zeppelin II is also a sexually charged album. “I think most of our music is,” shrugs Page who is also dismissive of the reputation that built up around the band and their carnal exploits around that time.

“Let’s put it this way: I certainly wasn’t going to bed with a cup of cocoa!” he snaps. “I was living it, for sure. But as far as I’m concerned, it’s all about the music but I also know that given people’s salacious appetites, all the little bits of scandal and everything else, it all gets absorbed. But it’s the music that’s lasted all these years and, you know what, that’s not about one stupid incident that happened in Seattle on a day off.”

“People think Stairway To Heaven was written down there and that’s absolutely not true”

Jimmy Page

The fabled incident at Seattle’s Edgewater Inn – involving a red snapper and a red-headed groupie – in July 1969 lies at the heart of Zeppelin’s cruel reputation for debauchery. Tour manager Richard Cole would later take full responsibility for the unsavoury matter.

“Most people who were there, their stories are so colourful and changed for after dinner speaking that it all becomes removed from the truth,” says Page, considering the endless tales re-told by so-called Zeppelin insiders. “Admittedly everyone in the group may have a different perspective on events but most other people take outrageous license with this stuff. Yes, like I said we were living it, but for me – and this will be the epitaph of it all – it was about a bunch of musicians who learnt about rock’n’roll, blues and serious acoustic guitar players and lots of other areas, and ended up creating a textbook for musicians. That’s the lifetime achievement right there. It’s not some sort of scandalous tit-bit, it’s about the real serious weight of it, about what the music really means. That’s it.”

“People think Stairway To Heaven was written down there and that’s absolutely not true because I had some of that worked out before then,” says Jimmy Page, embarking on his memories of Bron Yr Aur, the remote 18th Century cottage in Snowdonia which provided both him and Robert Plant with such rich inspiration as they took a break from the band’s hectic tour schedule in mind-1970.

“We went down there to have a break but we took the guitars with us. I was playing all the time at that point anyway, so it felt natural,” recalls Page on the subject of the first of two visits to the cottage that Robert Plant had visited with his family while on holiday as a child. In this rural idyll three miles north of the town of Machynlleth, with no electricity and no running water, Page and his partner of the time, Charlotte Martin, and Plant (along with his wife Maureen and daughter Carmen) as well as two members of Zeppelin’s crew settled into a suitably bucolic routine.

“There was a wooden fire so we’d go out and collect the wood for it. We had a couple of cassette players where we’d record ideas,” says Page. “We had the families there to start with and we were sort of playing things. That’s The Way was the main thing that came out from that first trip down there. We went out of for a walk and I took the guitar with me and I remember looking at the hillside and the whole panorama and it was just beautiful, beautiful. I remember playing that riff and just shaping things. You were there in the moment. We tinkered around with it before, the riff, but suddenly, we had the whole sequence.”

If Page found the splendid isolation of Bron Yr Aur inspiring, the idea of working with acoustic guitars was not new to him. “Basically, everything I’d ever written, even in The Yardbirds days and previous to that, had started out on an acoustic. I was using an acoustic but I was thinking electric,” he nods. “Acoustic music had also been there from the first album and even on II, but I did feel we could go somewhere else on III.”

In preparation for the band’s third album, Page had also worked up the arrangements to two songs that he felt might be suitable – the aforementioned Immigrant Song and Friends, the latter penned at his Pangbourne boathouse.

“It was written after a massive, massive argument with my current lady at the time,” he admits. “I just remember getting the guitar, and I had it in this tuning, and what I played came out like that. It was a combination of everything I was listening to, which was a lot of Indian music, a lot of Indian classical music.”

Page also began routining Gallows Pole, a Child ballad that Leadbelly had adapted in the 1930s. The version that inspired Page was by American folk singer Fred Gerlach who employed a 12-string on his take on the tune, and whose version Jimmy heard while visiting his then-girlfriend, the songwriter Jackie DeShannon, in LA in 1965.

“Jackie turned me on to Fred Gerlach but she didn’t just play me that track. Dick Rosmini was another one There was album of acoustic stuff by him she played me but Gallows Pole stuck with me and now it came into play. I knew it could be done with this band. I thought we’d hold it on the dynamics before John Bonham comes in. That whole thing of getting to know John Bonham’s playing meant that it seemed a natural thing, not to leave him out of the song but to bring him in for major effect.”

“If the band’s folk influences became more prominent on their third album, the blues also remained as a key component of their sound”

Jimmy Page

As well as Gallows Pole, DeShannon’s influence can also be felt on Tangerine, essentially a simple love song and another track that Page had stockpiled during his Yardbirds days.

“I’d written parts of that song even before I’d joined [The Yardbirds] but that song is definitely the result of us having met,” admits Page coyly. “I think the original words were different. We tried a version with the Yardbirds and there was a different chorus. It kinda got lost. I had songs I had written down the years but I didn’t push them, I was waiting to see whether they would fit and, on the third album, it fitted perfectly. It’s this little vignette with the pedal steel on there.”

If the band’s folk influences became more prominent on their third album, the blues also remained as a key component of their sound, most notably on a track which would become one of their best loved live outings: Since I’ve Been Loving You.

“It [Since I’ve Been Loving You] was a way of getting a low-key, cool sort of thing that still had the passion and the feel of the blues but to move it forward beyond the 12 bar blues of, say, The Lemon Song on II. Then we also had the country blues represented on Hats Of To Harper.”

Dedicated to recalcitrant British acoustic pioneer Roy Harper, Hats Of To (Roy) Harper captures Page and Plant locked in at Olympic Studios with engineer Andy Johns, delivering a deeply psychedelic version of country blues.

“We went in there specifically to try out these blues ideas. We got the harmonica involved with some double tracking using a small amp, like a Vox AC 30 with the tremolo. Robert was also singing through the amp.”

Stretching out for what Page recalls was “a 20 minute jam”, the duo ran through Memphis Minnie’s Keys To The Highway and Big Bill Broonzy’s Trouble In Mind. Both appear as one edited track on the companion disc for III.

“Key To The Highway really makes the hairs stand-up on the back of your neck,” smiles Jimmy. “You really do go ‘What is that?’ We cut Hats Off The Harper that same night and with that same feel.”

The final track on the album, a gentle goodnight it is not bringing to close a second side that is otherwise acoustic in texture.

Jimmy Page looks upset, almost hurt. The reason for this is because MOJO has just asked him about how recording at Headley Grange affected the sound on Led Zeppelin III.

“We didn’t go to Headley Grange for III,” says Page, shaking his head. “You should know that.”

Baffled by this rebuttal, your correspondent looks to his notepad for reassurance and finds none other than the name of the former East Hampshire poorhouse which was transformed into a residential rehearsal studio in the late ‘60s.

“You’re not the first person to mention Headley Grange in connection with III but it’s complete rubbish. I should know, I was there! III was done at Olympic and Island,” continues Page. “But that’s the way it is with Led Zeppelin: there are so many stories that are just plain wrong and no one tries to find out whether they’re true.”

As the conversation comes to a close, MOJO vows to inform Page of the source of this error. Further inspection reveals that 1993’s Led Zeppelin: The Complete Studio Recordings box set lists Immigrant Song, Friends, Celebration Day, Gallows Pole, Tangerine and Bron Yr Aur Stomp as all having been recorded at Headley Grange. “We shall have to blame Atlantic!” says Page upon receiving the information.

“I still think III is a fabulous album and I suppose the real significance was in the way in which we approached some of the material at Bron Yr Aur,” concludes Page on the album that hit Number One in both the US and UK on release in October 1970. “It made me think that if we could write in that kind of environment, then maybe we could record as a band in that way too. That’s what happened on IV. And that’s when we moved in to Headley Grange. That was when the band was really writing en masse all the time and things really opened up. If you have to, I suppose you could say that III is what set us on that path.”

Images: Getty